Introduction

This article profiles recent research from the Institute for Housing Studies (IHS or the Institute)1 on the topic of displacement, gentrification, and the role of public investment in driving neighborhood change. It discusses a specific public investment in Chicago and its role in accelerating gentrification, and highlights a new data tool created by IHS to help community development practitioners develop affordable housing strategies in advance of planned public investments.

Using data to get ahead of neighborhood change

Neighborhood change, particularly change as a result of gentrification and involuntary economic displacement, is a central community development issue being discussed in many cities and regions across the country. This issue is critical because a key principle of the work of community developers is promoting economic and social diversity in communities, even as many affordable neighborhoods are increasingly isolated and lack sufficient investment. Despite a broad interest in the topic and its importance for inclusive and equitable development, gentrification and displacement are notoriously difficult to study and even more difficult to predict.2 Generally, once gentrification and displacement can be measured, the opportunity to intervene to preserve affordability and mitigate displacement has passed.

Understanding public investment’s role in accelerating displacement pressure

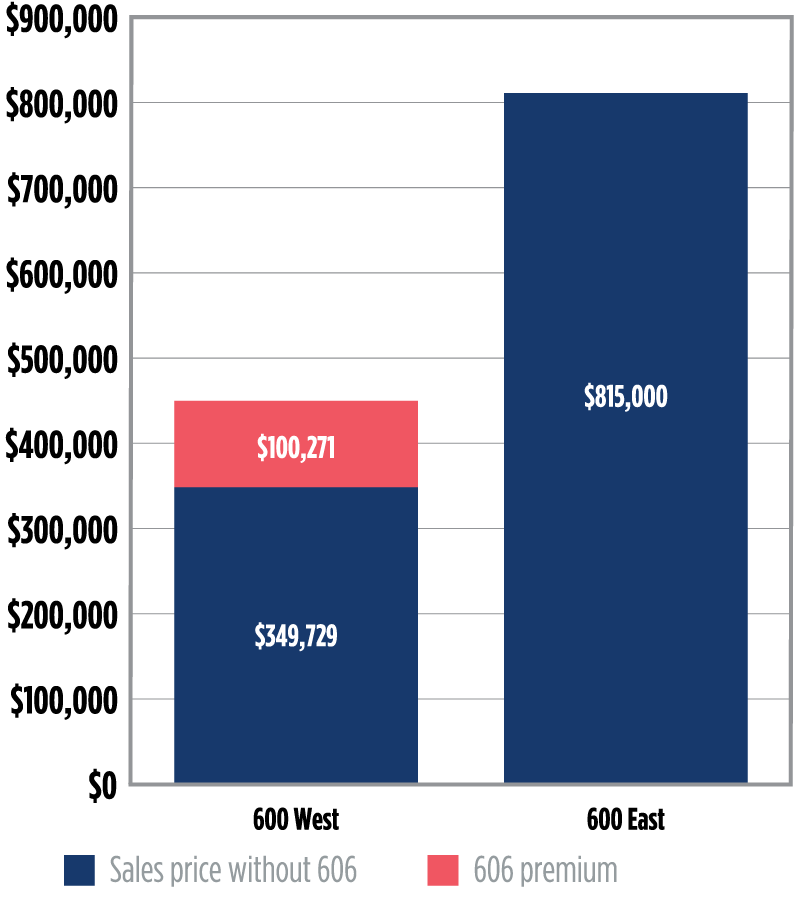

With plans for the development of the Obama Presidential Center on Chicago’s South Side well underway, talk of gentrification and displacement has been the subject of recent local news stories and public policy discussions. Concerns that newcomers, not existing residents, will benefit most from new neighborhood investment, and that rising prices and decreased affordability may lead to displacement, are not unwarranted. Recent IHS research studying the impact of The 606, Chicago’s northwest-side addition to the growing number of the rails-to-trails projects in cities nationwide, found that soon after the project secured funding, house prices increased dramatically in the surrounding neighborhoods. Much of this increase could be attributed to a premium buyers were willing to pay for houses close to the trail (figure 1), placing current homeowners at risk for displacement.3

Figure 1. Estimated impact of The 606 on 2015 median single family prices, 606 West and 606 East

Measuring the Impact of The 606, a 2016 IHS publication, estimated The 606 premium at over $100,000 for homes within one-fifth of a mile of the trail’s lower-income, lower-cost western half.4 This suggests that the timing of policies and interventions to preserve affordability are critical to their success. The research revealed other key principles relevant to preserving housing affordability amid planned investment, namely that displacement risk associated with lost affordability may be conditional upon relative home values in adjacent/nearby neighborhoods. For example, IHS was unable to detect a premium in more affluent neighborhoods surrounding the trail, supporting existing research suggesting that when it comes to the impact of investment on house prices, neighborhood conditions matter.5

Mapping displacement pressure citywide

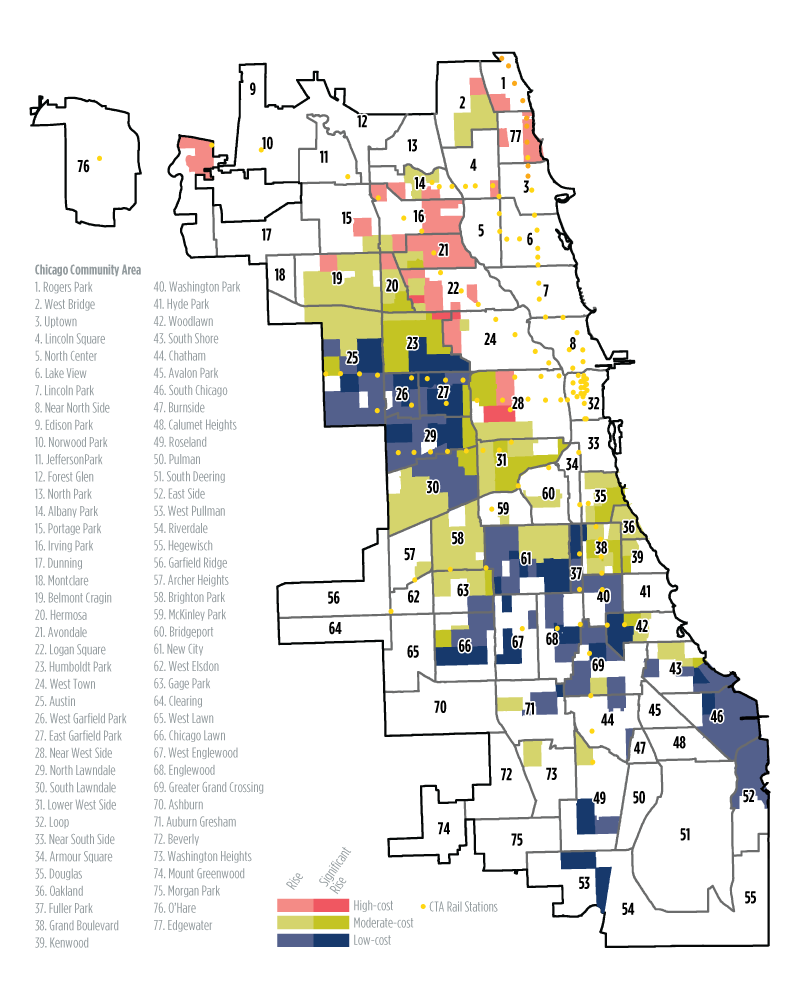

In order to operationalize the lessons learned from Measuring the Impact of The 606 and facilitate more inclusive and equitable development through proactive policymaking to preserve affordable housing, the Institute recently released Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago.6 The goal of the project is to create a leading indicator for displacement risk by constructing a framework to understand the intersection of 1) resident vulnerability to displacement in a rising cost environment and 2) housing market conditions associated with changing levels of affordability. Simply put, to identify places where people are vulnerable to displacement when housing costs go up and where prices are on the rise.

IHS approached the project by first constructing two separate data layers, one focused on the housing market and the second on the current demographic, socioeconomic, and housing stock composition of Chicago neighborhoods. Using geospatial techniques and the Institute’s unique data on property sales, IHS first created a typology of city neighborhoods based on current property values (high-cost, moderate-cost, or lower-cost) and recent change in house prices (declining, stable, rising, or significantly rising).7 The second component of the analysis used clustering techniques to segment the city of Chicago into six separate neighborhood types based on characteristics of the housing stock, as well as socioeconomic and demographic factors linked to heightened displacement risk. These factors include neighborhoods with high numbers of seniors, renters, households with lower incomes and/or already high housing cost-burden, as well as populations who often lack stable housing situations and/or have limited housing choice.8

IHS used these two analyses to 1) identify neighborhoods with rising costs where the underlying population is vulnerable to displacement and, from this group of neighborhoods, 2) create a typology of displacement pressure based on current housing costs in the market. The resulting analysis showed that many vulnerable communities in Chicago have some degree of displacement pressure due to rising costs, but that these conditions vary. IHS identified three displacement-risk types based on the current level of affordability:

- High risk of displacement (high-cost markets) – Due to the mix of vulnerable populations and high and rising housing costs, affordability pressure is substantial in these neighborhoods and displacement is likely already occurring.

- Moderate risk of displacement (moderate-cost markets) – In these neighborhoods, cost-burden is likely high due to low incomes and not yet exacerbated by high housing costs. However, values are rising, and areas near high-cost markets, amenities like transit improvement projects, or large-scale new development may be at risk of heightened demand from investors targeting new high-income households, which may push values beyond current affordable prices.

- Lower risk of displacement (lower-cost markets) – In these areas, values are too low to signal displacement from rising cost and rising prices are a positive trend. Long-term disinvestment is likely a more critical concern impacting patterns of neighborhood change, such as population decline.

Figure 2. Vulnerable city of Chicago submarkets with rising sale values, 2016

Figure 2 maps neighborhoods in the city of Chicago with different types of displacement pressure based on our analysis. The map shows that the majority of communities with vulnerable populations and rising costs are situated on the south and west sides of the city where displacement risk is currently minimal due to low values. These lower-cost neighborhoods have seen recent market movement, but still require significant investment and long-term strategies to rebuild housing demand before displacement due to rising costs becomes an issue. Areas with moderate costs, vulnerable populations, and rising values include a diverse set of neighborhoods on the far northwest side and in the central city. For neighborhoods close to amenities like transit (as indicated by the rail stations on the map) or close proximity to strong real estate markets, costs could shift and risk for displacement for vulnerable populations is therefore moderate.

Despite representing the smallest group of communities vulnerable to displacement, neighborhoods with high costs are of most immediate concern. These areas are likely undergoing active gentrification pressures and are highly clustered on the north and northwest sides of the city. Among this group is a small sliver of a neighborhood on the northwest side that was last ranked as affordable in 2012, but is now among the most expensive markets in the city – the vulnerable communities along The 606.

Using this lens to inform proactive policy for inclusive development

In Chicago and cities across the country, a number of place-based efforts are currently underway with wide-ranging goals to improve public health outcomes, mitigate the effects of climate change, reduce racial inequities, and raise the quality of life for residents of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. For these types of place-based investments and strategies to be successful, proactive affordable housing planning is essential to ensure vulnerable residents are not displaced before they can benefit.9

The development of a lens through which practitioners and policymakers can assess conditions and needs at the neighborhood level is critical to preserving affordability and mitigating displacement. Each of these displacement risk types have different neighborhood-level drivers of demand, current conditions, and ultimately different policy interventions aimed at preserving housing affordability. For example, strategies in high-cost markets are limited but can take advantage of market demand to build new units, even as market-rate affordable units disappear. Where costs are currently more affordable, robust policy interventions to preserve affordability can be developed in tandem with planned investment and can even be aligned with broader strategies such as building wealth through homeownership for some moderate-income households. As part of its release, IHS developed a set of fact sheets to help frame policy interventions with the needs and realities of these three market types.10

To provide a mechanism for practitioners to more broadly apply the analysis to understand conditions around future and planned investment projects and a data-informed starting point for developing neighborhood-level housing policy strategies that preserve affordability, IHS also built an interactive mapping tool.11 The tool allows stakeholders to explore displacement risk conditions across the city and the full context of market conditions and vulnerability for neighborhoods surrounding The 606 and upcoming projects including Chicago’s second rails-to-trails project El Paseo and the Obama Presidential Center. IHS is also currently working with community-based organizations and policymakers to apply this analysis to identify displacement risks around ongoing community development strategies in the city, such as environmental improvements along the Chicago River, infill development around underutilized transit stations, and targeted public health initiatives.

NOTES

1IHS is an applied research center based at DePaul University in Chicago that produces research and data tools to inform housing and community development policy decisions and discussions in the Chicago region and nationally. See www.housingstudies.org.

2Zuk, Miriam et al., 2015, “Gentrification, Displacement and the Role of Public Investment: A Literature Review,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, working papers, August 24, available at https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/working-papers/2015/august/gentrification-displacement-role-of-public-investment.

3Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University, 2016, “Urban Trails as Urban Planning,” October 19, available at https://www.housingstudies.org/news/blog/urban-trails-urban-planning.

4Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University, 2016, “Measuring the Impact of The 606,” November 1, available at https://www.housingstudies.org/research-publications/publications/measuring-impact-606.

5Heckert, Megan et al., 2012, “The Economic Impact of Greening Urban Vacant Land: A Spatial Difference-In-Differences Analysis,” Sage Journals, January 1, available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1068/a4595.

6Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University, 2017, “Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago,” December, available at https://www.housingstudies.org/media/filer_public/2017/12/18/ihs_mapping_displacement_pressure_in_chicago_technical_2017.pdf.

7IHS Data Clearinghouse, available at https://www.housingstudies.org/data/about-data-clearinghouse.

8Bates, Lisa K., 2013, “Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an equitable inclusive development strategy in the context of gentrification,” City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, available at https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/454027.

9Immergluck, Dan, 2017, “Sustainable for Whom? Large-Scale Sustainable Urban Development Projects and ‘Environmental Gentrification,’” September 1, available at https://shelterforce.org/2017/09/01/sustainable-large-scale-sustainable-urban-development-projects-environmental-gentrification.

10IHS Preserving Affordability Fact Sheets, available at https://www.housingstudies.org/media/filer_public/2017/12/21/ihs_mapping_displacement_pressure_in_chicago_fact_sheet_2017.pdf.

11Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago, available at https://displacement-risk.housingstudies.org.