The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Credit card loans at commercial banks in the U.S. increased by $72.4 billion from 1980 to 1987. Just two states accounted for half of that increase—Delaware for $25.0 billion and South Dakota for $12.3 billion.

This remarkable performance by two small states—both are well under a million in population—is largely the result of legislation by the states themselves. The strategy has been to legislatively encourage bank holding companies from other states to establish subsidiaries in new and commercially attractive surroundings, bringing with them new jobs and higher tax receipts for South Dakota and Delaware.

In contrast to results in these states, where percentage increases in credit card loans must be measured in tens of thousands, the national increase was 243% from 1980 to 1987 (see table). States of the Seventh Federal Reserve District in general performed worse than the national average. (Iowa was an exception.) Some states saw big drops in credit card loans: Texas was down 66% and Oklahoma, 65%.

1. Credit card loan growth (1980-87)

| Commercial banks | (percent) |

|---|---|

| U.S. | 243 |

| Illinois | 36 |

| Indiana | 215 |

| Iowa | 319 |

| Michigan | 110 |

| Wisconsin | 106 |

| Delaware | 24,375 |

| South Dakota | 207,876 |

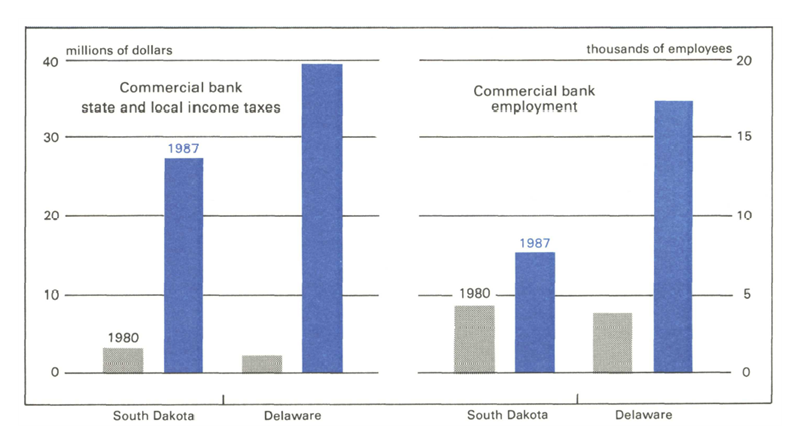

Changes in commercial bank employment and state income taxes paid also reflect the successes of South Dakota and Delaware. From 1980 to 1987, U.S. commercial bank employment rose 7%. In Delaware and South Dakota, however, it was up 347% and 75%, respectively (see figure). Banking employment actually declined during this period in 16 states, including Michigan, Illinois, and Iowa in the Seventh District.

2. The rewards of innovation

At the same time state and local income taxes paid by commercial banks in Delaware increased from $2.4 million in 1980 to $39.5 million in 1987 and in South Dakota from $3.2 million to $27.2 million.

Early and aggressive, South Dakota and Delaware have captured a significant share of the credit card market by creating a regulatory environment that has attracted financial services organizations. The marketing strategies and experiences of these states may serve as a warning to others that a failure to maintain a competitive banking environment will lead to a loss in jobs.

The lessons to be learned apply not only to credit cards. Technological advances have greatly increased the ability of bank holding companies to move many different bank operations to states that create more attractive environments. Once a state loses such an operation, it is difficult to recapture.

Backgrounds: Law and technology

The Supreme Court in 1978 affirmed the right of a national bank to charge interest rates to out-of-state credit card customers at the rate permitted by the law of its home state. In other words, a national bank with a credit card operation in a state with a high or nonexistent ceiling rate on consumer loans could charge a higher rate on credit card balances or loans to credit card holders living anywhere in the country.

Such added pricing flexibility on consumer lending presented an opportunity for states to increase commercial banking transaction activity and employment. By increasing or eliminating ceiling rates on consumer loans and granting permission to out-of-state bank holding companies to own national bank subsidiaries, state legislators could encourage such companies to establish subsidiaries engaged primarily in national credit card operations. Other inducements could be permission to charge annual fees for credit card or loan privileges, lower tax rates on bank net income, and a plentiful, educated labor force. Once established, bank operations were unlikely to move back to the original state or elsewhere unless a new location could demonstrate distinct advantages.

Technological improvements have facilitated the ability of bank holding companies to locate certain banking operations in other states. The availability of electronic data transmission and funds transfers and other communication facilities no longer requires that all banking operations be located in the vicinity of the majority of a bank’s customers.

First off the mark: South Dakota

South Dakota was the first state to enact commercial banking legislation specifically aimed at bringing out-of-state banking operations to the state to create jobs, expand the economy, and increase tax revenues. In February 1980, South Dakota removed all usury ceilings for credit card loans and other types of consumer lending. In March, the state amended its banking laws to permit an out-of-state bank holding company to establish a single state or national de novo bank in the state and move its credit card operations there. Such a bank was limited to a single banking office and was to be operated in a manner and at a location that would not attract customers from the general public. (Subsequent legislation has eliminated most of these original restrictions.)

New York’s Citicorp was the first out-of-state bank holding company to establish a new national bank in South Dakota. The new bank, Citibank (South Dakota), N.A., at Sioux Falls, was to engage primarily in nationwide consumer credit card lending activities then currently conducted by Citicorp’s New York banks. After seven years, it is now the largest commercial bank in South Dakota, with domestic assets of $12.0 billion, total loans to individuals of $11.6 billion, and 3,462 employees.

Other out-of-state bank holding companies from Texas and Nebraska also established subsidiaries in South Dakota, primarily to offer credit card services. At the same time, two large bank holding companies with headquarters in Minnesota expanded consumer loans and employment at existing subsidiary banks in South Dakota.

Delaware spreads a broader net

Delaware followed South Dakota with similar legislation aimed at the development of commercial banking. The Financial Center Development Act of 1981 (FCDA) allowed out-of-state bank holding companies to operate only a single office that was not likely to attract new customers from the general public. The bank was required to employ at least 100 people within one year in the state. FCDA also essentially eliminated interest rate ceilings on all types of loans including bank revolving credit (i.e., credit cards) and bank closed-end credit and permitted banks to charge fees for the borrowing privileges (i.e., annual card fees). In addition, the law included an attractive bank tax structure with declining tax rates as bank net income increased.

By the end of 1987, 17 FCDA banks had opened and one was pending. The major contributors to the expansion of assets and employment in the commercial banking industry in Delaware have been these banks. Eight are subsidiaries of bank holding companies in New York and are variously engaged in wholesale banking, cash management services, nationwide commercial lending, as well as consumer lending and credit card operations. FCDA banks that are subsidiaries of bank holding companies in Georgia, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, are primarily engaged in consumer lending and credit card operations.

In 1983 Delaware enacted two additional banking laws. The banks established under these laws have had a smaller impact on the growth of assets, total loans, and employment at commercial banks in Delaware. Part of this is attributable to the more recent enactment of the legislation.

The Delaware legislation has also encouraged the establishment of so-called nonbank banks by out-of-state companies. Such nonbank banks have usually been acquired or established by nonbank holding companies, primarily for the purpose of offering consumer loans and credit cards, or alternatively, offering commercial loans but not accepting demand deposits.1 Eight nonbank banks are in operation in Delaware. Employment increased over 3,000 at Greenwood Trust Company alone (New Castle, Delaware), after it was acquired by a subsidiary of Sears, Roebuck and Company in January 1985 and began offering the new Discover credit card.

Delaware’s 11 continuing commercial banks also benefited from the legislation to encourage the expansion of banking employment in the state.

In the Seventh District

After the successes in South Dakota and Delaware, other states, including those in the Seventh District, found it necessary to play follow-the-leader. Some of the banks in these states were either moving their credit card operations to South Dakota or Delaware or were threatening to do so.

Illinois

Illinois was the first of the Seventh District states to eliminate interest rate ceilings on bank credit card loans in 1981. The maximum annual fee for the privilege of receiving and using revolving credit continued at $20.

Assets, loans, including credit-card related loans, and employment at Illinois’ commercial banks have shown aggregate growth substantially below the national average from 1980 through 1987. The effects of the removal of the interest-rate ceiling have been obscured by other developments in the banking industry in Illinois. The aggregate increase for Illinois in credit card loans was only $2.7 billion. During the same time reported banking employment in the state declined 1,998. During 1987, First Chicago Corporation acquired a nonbank bank in Delaware and has expanded its credit card operations at the Delaware bank.

Indiana

Indiana also found it necessary to lift usury ceilings. It increased the interest rate ceiling on all types of lending (except open-ended revolving credit cards) from 18% to 21% in 1981. In 1982 the Legislature also increased the interest rate ceiling on credit card loans from 18% to 21%. Annual credit card fees are unlimited.

Growth in total domestic assets, loans, and deposits was below the national average in Indiana from 1980 through 1987. The state’s banking employment was up only 1.5% during this period compared to 6.7% nationally.

Iowa

South Dakota’s neighbor was among those states that enacted legislation to keep commercial bank credit card operations in-state. At least one major bank in the state had indicated that it would seriously consider moving its credit card operations elsewhere if the legislation were not passed. In 1984 Iowa approved a measure that eliminated the interest rate cap on bank-issued credit cards. Annual fees for credit cards or loans are permitted without limit.

Growth in commercial bank loans for credit cards in Iowa was well above the national average from 1980 to the end of 1987. A major contributor to this growth was the largest bank card issuer in Iowa, Norwest Bank Des Moines, N.A., a subsidiary of Minneapolis-based Norwest Corporation, which had consolidated its nationwide credit card processing from three states in Des Moines in 1981. From 1980 through 1987 credit-card related loans at the bank increased five-fold and reported employment at the bank increased from 581 to 1004 to make it the largest bank employer in the state.

Michigan

Despite legislative attempts, Michigan has been unable to increase the interest rate ceiling on consumer loans and, particularly, bank credit card loans. On any loan made pursuant to an existing credit card arrangement, interest and charges in a combined amount may not exceed 1.5% of the unpaid balance per month. As a result of the usury laws, several large Michigan bank holding companies have established subsidiaries in states with either much higher or no interest rate ceilings on consumer loans.

Growth in assets, loans, and deposits at Michigan commercial banks between 1980 and 1987 has been well below the national average and the percentage increase in credit card-related loans has been less than half the national rate. During this period banking employment declined 2,035, or 4.2%

The decline in employment at Michigan banks appears to be the result of several factors. With the ceiling on interest rates, the profitability of credit-card loans was limited, particularly during the high interest days of the early 1980s. Part of the declining employment was probably caused by the consolidation of banks and their establishment as branches.

Comerica Incorporated, Detroit, was the first of Michigan’s bank holding companies to move credit card operations to a nonbank bank in Ohio, in 1983. NBD Bancorp, Inc., Detroit, established a consumer credit bank, NBD Delaware Bank, Wilmington, under Delaware’s laws in 1984. Manufacturers National Corporation, Detroit, established Manufacturers National-Wilmington, in Newark, as its consumer credit bank in Delaware in 1986. Michigan National Corporation, Farmington Hills, received permission from the Federal Reserve Board to acquire Independence One Bank, N.A., Rapid City, South Dakota, in 1986 but operation of the bank has been subject to litigation.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin also has limited the interest rate on credit-card related loans to 18%. Unlimited annual card fees are permitted. Rates of growth in assets, loans, and deposits at Wisconsin’s commercial banks between 1980 and 1987 have been similar to those in Michigan. Banking employment, however, increased 1,054, or 4.6%.

The lessons

What is to be learned from the successes of South Dakota and Delaware in garnering new financial business? Or, from the losses other states have suffered?

Lesson Number One is that changes in banking laws and great advances in technology have made it much easier for banking organizations to move certain operations. Lesson Number Two is that banks and bank holding companies have already learned Lesson Number One, and are moving operations out of state when attractive opportunities are presented to them.

Some states have already profited from these changes. But, in the other states, in the Seventh District and elsewhere, development planners and legislators should look for ways to attract new financial operations. They must learn how to market these incentives. And clearly, state legislators must balance the trade-off between consumer protection and the possible consequences to their financial services industry.

MMI—Midwest Manufacturing Index

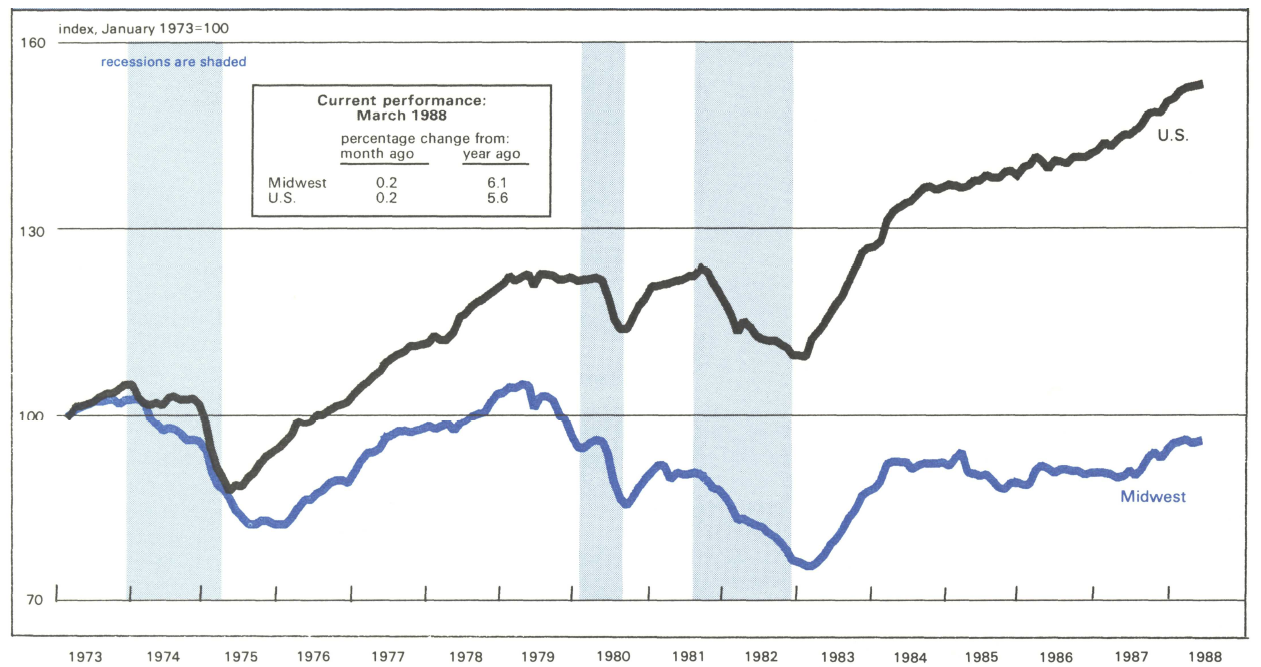

Industrial production in manufacturing nationwide improved slightly in March, after being flat in February. Production in the first quarter of 1988 has been markedly slower than in the previous quarter, largely because of softness in the nondurable goods sector.

Manufacturing activity in the Midwest also edged up 0.2 percent in March, following a February decline. However, most durable-goods industries in the Midwest were virtually unchanged from the previous month. Over the first quarter, the MMI shows less growth than the Board’s Production Index for the nation, largely because durable-goods industries in the Midwest have not kept pace with the nation. Even primary metals, which boosted the MMI in the fourth quarter, has been slipping in recent months.

Note

1 The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 (BHCA), as amended, defined a commercial bank subject to the regulation under BHCA as one that accepted demand deposits and made commercial loans. If both of these conditions were not present, national or state-chartered banks were not subject to regulation under BHCA and became known as nonbank banks.