The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

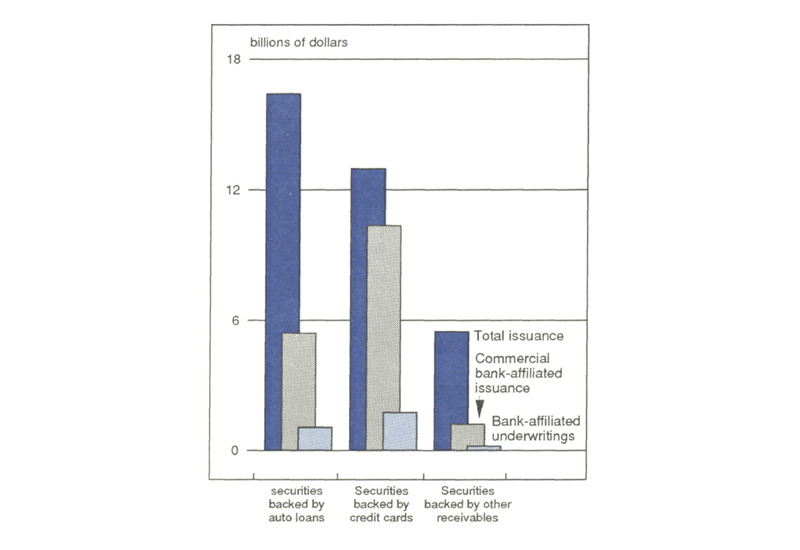

A lot of people do. And not only car loans. Investors have, in effect, bought over $16 billion in consumer loans from commercial banks by buying securities backed by automobile loans, credit card receivables, home equity loans, and other consumer debt.

More than 90% of these issues were underwritten by independent investment banks. The underwriter buys the issue for a fixed price and resells it through its distribution channels to its customers at a higher price. While commercial bank firms play a big role in issuing asset-backed securities, they have played a relatively small role in underwriting them. They would like to underwrite more, but their authority to do so is limited.

As things now stand, a bank that is securitizing loans cannot have an affiliate underwrite the issue. It must turn to an outside firm. This restriction is aimed at protecting investors by avoiding a potential conflict of interest between a bank’s underwriting and loan origination functions.1

In making this ruling, regulators were concerned about the quality—and the appearance of quality—of assets sold by commercial banks. Absent other controlling factors, when the buyer has to take the seller’s word about the quality of the assets being sold, sellers have strong incentives to try to sell “lemons” as if they were “plums.” This so-called lemons problem was first analyzed in a famous paper by George Akerlof, in which he develops a model market for “lemons” in terms of the used-car market.

This Letter questions whether prohibiting a bank holding company from underwriting its bank’s asset-backed securities provides important and necessary protection to the investor. It concludes that there are many other players who ensure the quality of asset-backed issues. Their presence effectively dilutes the danger of dealing in lemons dressed up as plums.

The lemons problem

When information is biased either toward buyers or sellers (asymmetric information), as is the case when buyers cannot distinguish lemons from plums, institutional and contractual arrangements are necessary to permit markets to function. Generally when sellers have more information about the quality of the specific asset being sold than do buyers, the prevailing price will be for average quality assets because prospective buyers know that a certain proportion of assets being sold are plums and a certain proportion, lemons. They are only willing to pay a price for the asset that is consistent with their expectations about the overall quality of the asset. This creates incentives for sellers to sell average or below-average assets, further decreasing the proportion of good assets in the market and further depressing the price until the bad drives out the good.

One solution to this problem is to offer guarantees; others include brand names, chains, licensing, and certification. With the exception of guarantees from sellers to buyers, each of these arrangements requires someone’s reputation to be at stake.

It follows that the value of a license, certification, or third-party guarantee is only as good as the reputation of the provider. Assuming that the provider has a good reputation for weeding out inferior products, because he has better information than buyers, licensing and certification convey that the seller or product meets a certain minimum standard. Third-party guarantees either indicate that a product is of a certain quality or enhance the quality to bring it up to that certain level.

Many markets plagued by asymmetric information and quality uncertainty thrive with only one or maybe two of these protections. For example, most consumer durable goods carry a manufacturer’s warranty, and consumer packaged goods are often sold under a reputable brand name. They might come, too, with a moneyback guarantee. Professionals, such as doctors, lawyers and accountants, generally operate with licenses and certification.

No lemons for sale

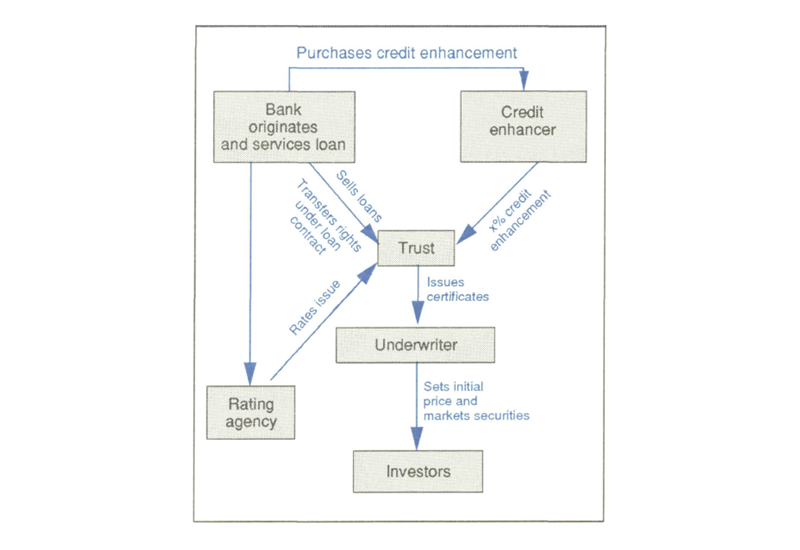

In the market for asset-backed securities, however, most issues are structured to provide for several forms of protection against lemons. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of an issue of pass-through securities. Pass-through certificates, perhaps the most popular form of asset-backed securities, represent direct ownership in a portfolio of assets.

1. Structuring asset-backed issues

As shown in figure 1, the originator, after funding the assets, sells them. Originators, or affiliates of originators, are usually also the servicers of the loans they sell. Servicers are responsible for collecting principal and interest payments on the assets when due and for pursuing the collection of delinquent accounts.

Thus, the originator/servicer is at the heart of the “lemons” problem in loan sales transactions. This player knows, or at least is better able to assess, the quality of the loans that are sold. Also, through his effort, or lack of effort, in servicing the loans, he is instrumental in determining the actual yield that the buyer realizes on the assets.

Originator/servicers take certain steps themselves to reduce quality uncertainty. For example, securities are issued under “brand names” (e.g., Chemical Bank Trust 1988 A and First Chicago Master Trust A) so that investors associate the securities with the originator, who presumably has a good reputation in loan origination and servicing. In addition, originators will often signal that they intend to sponsor more issues of asset-backed securities by announcing that asset-backed securities are a fundamental source of financing and by setting up master trusts. A master trust, while initially more costly, allows an issuer to make continuous offerings of securities with minimal additional work and, therefore, signifies the issuer’s intention to sell asset-backed securities repeatedly.

In many asset-backed structures these assurances by originators are not sufficient; therefore, other players and contractual arrangements ensure quality and performance. These solutions include trustees, credit enhancers, rating agencies, and underwriters.

The trustee

In the pass-through structure illustrated in figure 1, the originator sells the assets to a trust. The trustee, then, on behalf of the trust, issues certificates through an underwriter to the investors. As the borrowers make principal and interest payments on the loans, the servicer deposits the proceeds in the trust account, and the trustee passes them on to the investors. If funds are insufficient to pay investors, the trustee draws on the credit enhancement, which is often a letter of credit.

In addition to “servicing” the asset-backed securities, trustees are also responsible for monitoring the servicer of the underlying loans. Prior to the sale of an issue of asset-backed securities, the trustee will audit the originator/servicer and, throughout the life of the issue, the trustee will be responsible for determining the sufficiency of the various reports made by the servicer to the investors and for passing the reports on to the investors. These reports include an annual audit of the servicer performed by a certified public accountant.

Thus, the trustee is a middleman whose reputation is known and on the line. Standard & Poor’s requires that trustees be insured depository institutions with at least $500 million in capital; therefore, the function of trustee, at least for rated issues, is limited to only the largest banks, many of which have established reputations as bond trustees for a wide array of securities.

The credit enhancer

Credit enhancement provides another solution to quality uncertainty. It is a vehicle that reduces the overall credit risk of a security issue. Most asset-backed securities are credit-enhanced. Credit enhancement can be provided by the issuer or by a third party; sometimes more than one type of credit enhancement supports an issue. Credit enhancement provided by a third-party has taken on the form of either a letter of credit from a bank with a high credit rating or an insurance bond, also from a firm with a high rating.

While it may be argued that credit enhancers, like buyers, face a lemons problem, credit enhancers probably do not face the same problem buyers do. Third-party guarantors should possess better information than even the most sophisticated investors. Otherwise, a valuable guarantee could not be provided profitably.

For issues of pass-through securities, letters of credit and insurance bonds are the most common types of credit enhancement. This type of credit enhancement will cover some percentage of the underlying assets, usually a multiple of the expected bad-loan charge-off rate. Thereafter, the credit enhancement is reduced by payments made by the insurer to cover delinquencies and defaults. If the amount of credit enhancement is reduced to zero, the investors bear all subsequent credit risk.

The level of credit enhancement varies by type of assets securitized and within type by the default history of the issuer’s portfolio. The level required for a particular rating is largely determined by the rating agencies. Riskier deals require a higher level of credit enhancement.

The credit raters

Credit rating agencies assign ratings to asset-backed securities issues just as they do to corporate bonds. Rating agencies rate asset-backed securities by assessing the ability of the underlying assets to generate the cash flows necessary for principal and interest payments to investors. In rating an asset-backed securities issue, the rating agencies analyze the structure of the issue and then assess the credit enhancement.

The credit enhancement and credit enhancer are crucial to the rating of an issue. The level of credit enhancement, as well as the quality of the enhancer, are evaluated by the rating agency. An issue can be rated no higher than the credit rating of the credit enhancer. An issue, however, can receive a lower rating if the level of enhancement for that particular issue is judged insufficient.

Once a public issue has been rated by a credit rating agency, the agency monitors the issue regularly throughout the life of the issue for possible rating changes. An issue can be downgraded or upgraded. Rating changes result from changes in the credit quality of the credit enhancer or from changes in the credit quality of the assets securitized.

Rating agencies, therefore, are middlemen who provide a type of “certification” and whose existence depends entirely on their reputations. As one major agency puts it: “Credit ratings are of value only if they are credible. Credibility arises from the objectivity of the rater and his independence of the issuers’ business.”2 Several rating agencies have achieved such credibility. For over 75 years they have rated thousands of issues of corporate and government bonds. While misrating issues now and then probably does not materially affect the rating agencies, they have achieved reputations and influence that have made it “commonplace for companies and government issuers to structure financing transactions to qualify for higher ratings.”3 These agencies, therefore, impose a kind of market discipline.

The underwriter

Underwriters are a fourth player ensuring quality and performance in asset-back security sales. It is in this role that commercial banks would like to expand their participation. Underwriters purchase securities from issuers at negotiated fixed prices with the intention of reoffering the securities to investors at higher prices. While a nonbank issuer, a business firm, for example, could conceivably bypass the underwriter and offer its securities directly to the investing public, issuers actually receive greater net proceeds from the sale of their securities when they are sold through an underwriter because of his reputation for expertly pricing new issues and efficiently marketing and distributing newly underwritten securities.

Because this reputation is valuable, the participation of an independent underwriter helps resolve the lemons problem. If an issuer were to bypass the underwriting process or if an issuer and underwriter were affiliated through common ownership, the lemons problem would not be solved unless there were other arrangements that reduced buyers’ uncertainty about quality. Like rating agencies, underwriters have superior information and depend on their reputations of possessing such information for their existence. In fact, reputation is one of the most often cited barriers to entry in the area of corporate securities underwriting.4 The success of any issue can be critical to the success of future issues. “Success” is broadly defined by issuers as market acceptance. An investment bank’s biggest asset in this regard is its distribution network—a group of investors standing ready to purchase new issues. This asset, however, will be jeopardized if an underwriter sells securities that consistently go sour on its pool of investors.5

Conclusions

Underwriters are one solution to the lemons problem inherent in asset-backed securities transactions, but they are not the only solution. Underwriting asset-backed securities by an affiliate of the originator would eliminate that one form of protection and, therefore, weaken an asset-backed security’s structure. As long as other protections are in place, the actual impact is likely to be minimal.

In the finance arena, commercial banks and investment banks have already been selling loans with their reputations at stake but without the involvement of an impartial underwriter. Investment banks often extend bridge loans to clients until they can issue debt in the capital markets. The proceeds from the debt issue go to repay the bridge loan; so, when the investment bank underwrites the debt issue, it is, in effect, selling the bridge loan.

Similarly, in the last few years commercial banks, especially the largest, have become fairly active sellers of their own commercial loans. So far, it appears that commercial banks have chosen to sell high quality loans rather than their least creditworthy assets—lemons. During each quarter of 1988, the ten largest banks sold about $200 billion directly to purchasers; no independent underwriter was involved. These larger banks reported that no purchaser had to charge off loans that they had sold to them.6 In a group of smaller banks, only three reported that purchasers had to charge off loans that the banks sold. These loans amounted to a mere 0.7% of the dollar amount sold.7

2. Marketing asset-backed issues

In the case of asset-backed securities, the elimination of the “impartial judgment” of the underwriter would still leave investors with the unbiased evaluation of three parties: the trustees, the rating agencies, and the credit enhancers.

All publicly offered issues of asset-backed securities have been rated. In general, rating agencies will not rate asset-backed securities that are not credit-enhanced. And all issues require a trustee. So, as currently structured, any issue that a bank-affiliated underwriter would underwrite would have at least three independent evaluators. As long as these evaluators remain independent, the potential for conflicts of interest and adverse effects by allowing an affiliate of a commercial bank to underwrite securities backed by loans originated by the bank would be minimal.

Notes

1 In June 1987, the Federal Reserve Board approved the applications of three bank holding companies to underwrite, within limits, mortgage-backed securities as well as municipal revenue bonds and commercial paper. The following month, the Fed ruled that securities backed by consumer-related receivables should be afforded similar treatment to mortgage securities. The Comptroller of the Currency, in June 1987, permitted a national bank to sell publicly its own mortgage pass-through certificates. While the securities in question at the time were mortgage-related, the Comptroller made clear that his opinion also applies to other types of asset-backed securities. In December 1988, however, a U.S. District Court ruled that national banks could not underwrite securities backed by their own assets.

2 Standard & Poor’s Corporation, S&Ps Structural Finance Criteria, 1988, p. 3.

3 Standard & Poor’s Corporation, p. 3.

4 Betsy Dale, “The Grass May Not be Greener: Commercial Banks and Investment Banking,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Perspectives (November/December 1988), pp. 9-10.

5 Lawrence M. Benveniste and Paul A. Spindt, “Bringing New Issues to Market: A Theory of Underwriting,” September 15, 1988, mimeo.

6 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey for August 1988.

7 The next size class includes 40 large non-money center banks.