The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Since the beginning of 1990, the economy has been struggling in its attempt to reach an anticipated “soft landing.” The year began with auto inventories bulging and deep production cutbacks scheduled. Throughout much of the year, many firms suffered from weak profits and, in an effort to avoid losses, firms laid off white-collar as well as blue-collar workers. At midyear few forecasters were expecting the economic expansion to end, but fewer still were expecting a Middle East crisis and episodes of $40 per barrel oil. It now appears that the economy in 1990 ended on a sour note. Real gross national output (GNP) contracted for the first time since 1986, making the economy a little weaker and a little bumpier than expected at the beginning of the year.1 This disappointing ending occurred after the unforeseen and unprecedented drop in consumer and business confidence that can be traced in large part to the Middle East crisis. Most notably, the University of Michigan’s index of consumer confidence took the steepest plunge in its history after the August invasion of Kuwait. This loss of consumer confidence culminated in the fourth quarter of 1990 in the form of a weak Christmas selling season.

In an atmosphere of growing apprehension about the sustainability of the longest peacetime expansion on record, 28 business economists and analysts attended the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s fourth annual Economic Outlook Symposium on December 12, 1990, to discuss their economic outlook for 1991.

The consensus of the group was that the economy would continue to grow, but at roughly half the pace of 1990: a 0.4% rate of growth in real GNP in 1991, compared with 1.0% in 1990. But the more interesting story lies hidden in the quarterly growth pattern of the economy. With the longest peacetime expansion likely to end in 1991, the key question becomes how long and how deep will the economic contraction be? This Fed Letter highlights the consensus outlook and discussion that took place at the December symposium.2

Confidence shapes the consensus outlook

It is often said that no two recessions are exactly the same. Forecasting economic growth for 1991 has been made difficult because many of the traditional warning signs of an impending recession have not appeared in the current economic environment. This may be because businesses have been preparing for hard times since at least the beginning of 1990. For example, the group was developing their forecasts in an environment where inventories—relative to recent sales volume—were tightly controlled and extremely lean. Without the need for prolonged production cutbacks to help trim bulging inventories, sustained periods of economic decline are unlikely. Indeed, the economy ended the third quarter of 1990 with modest but still positive growth (1.4%), without the characteristic involuntary buildup of inventory normally seen in the early stages of a recession. Nevertheless, there were warning signs that the economy was beginning to contract prior to the symposium.

The consumer confidence index was perhaps the bleakest indicator of a deteriorating economic environment. This index has yet to recover from its steep decline following the invasion of Kuwait. The index of leading indicators also peaked in August and continued to decline through the end of 1990. Also, the national purchasing managers’ survey signaled the beginning of a sharp economic contraction in September. By the time of the symposium, data on employment and industrial production declines, led by cutbacks in the auto industry, confirmed what the indexes signaled—the fourth quarter of 1990 would be weak. The consensus prediction of the group at the time of the symposium was that GNP would decline by 1.5% (annualized) in the fourth quarter—the first quarterly decline since 1986. The group’s main concern was how long and how deep would be the economic contraction.

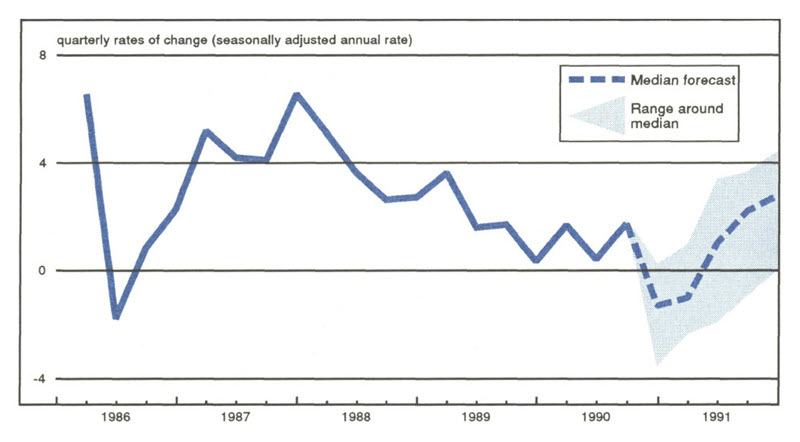

Based on the consensus outlook, real GNP is expected to follow the decline in the fourth quarter of 1990 with a 0.9% (annualized) drop in the first quarter of 1991 (see figure 1) before turning positive. According to the consensus, GNP will decline only 0.6% from peak to trough, compared to an average recessionary decline in GNP of 2.6%. Only the most pessimistic of the forecasts submitted at the symposium (as shown by the lower edge of the shaded area in figure 1) would begin to compare with an average recession.

1. Real GNP outlook—downturn and recovery

While the group expected economic growth to turn positive by the second quarter of 1991, the second quarter growth rate of 1.0% is anemic at best. Seven of the 25 forecasts submitted at the symposium showed declines extending through the first half of 1991. Only in the second half of the year did the group expect GNP growth to average about 2.5%, approximately the amount of growth achieved on average in 1989. Given a reasonable margin of error around the forecast numbers, the second quarter of 1991 could easily be the third consecutive quarter of economic decline.

Despite the softness expected in the second quarter, the first quarter of 1991 appears to be the pivotal quarter in the consensus outlook. As with the fourth quarter of 1990, virtually all of the sectors of the economy are expected to decline in the first quarter of 1991 (see figure 2). Although the pace of the contraction eases in the first quarter, enough momentum remains to keep the first quarter growth rate negative. In the second quarter, however, only business fixed investment continues to decline. An expected decline in net exports over 1991 tends to be offset by an expected rise in inventory investment in the second half of the year (change in levels not shown in figure 2). Gains in consumption spending and modest inventory rebuilding are sufficient to begin the process of economic recovery, albeit at a very tentative pace.

2. Quarterly pattern in consensus outlook

| Percent change (saar) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90Q4 | 91Q1 | 91Q2 | 91Q3 | 91Q4 | 1990 | 1991 | |

| GNP in constant (1982) dollars | −1.5 | −0.9 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | −1.5 | −0.3 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Business fixed investment | −5.1 | −3.7 | −1.9 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 1.4 | −1.4 |

| Residential construction | −14.2 | −5.9 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 5.6 | −5.0 | −6.1 |

| Government purchases | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| FRB index of industrial production | −3.7 | −2.5 | −0.4 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 1.2 | −0.2 |

| GNP implicit price deflator | 4.6 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

Note: Numbers are median forecasts of rates of change in GNP and related items.

The reason that the group predicted such tentative growth in the second quarter of 1991 may have been their expectation that the index of industrial production will continue to decline, marking its third consecutive quarterly decline. Some of the weakness in production can be attributed to the expected decline in investment, particularly producer durable equipment. However, production may be further weakened because consumer durables are slow to rebound from quarterly contractions. In other words, much of the growth in consumption spending is likely to come from trend growth in consumer services and from less cyclically sensitive nondurable consumer goods. Thus, according to the consensus, the economy is expected to remain sluggish until sales of consumer goods, such as autos and appliances, and producer goods, such as heavy equipment and computers, begin their recovery.

The group’s prediction of improvement in the second half of 1991 can be attributed in part to their expectation that interest rates will be lower during 1991 than they were at the time of the symposium. About 80% of the participants built lower interest rates into their forecasts. This expectation has already been justified to some extent by recent events. Short-term interest rates edged downward in December, in response to an easing in monetary policy that included the December 18 reduction in the discount rate. Assuming that changes in monetary policy lead the economy by six to nine months, a cyclical turnaround should be expected in the second half of 1991.3 Moreover, according to the consensus outlook, the improvements are expected to come from traditionally interest-sensitive sectors of the economy—the consumer and producer goods sectors. These same sectors typically generate the recovery phase to the business cycle as well.

Prospects for another auto-led recovery

Auto sales were by far the major source of growth in the economy during the 1983 economic recovery. That year, car and truck sales rose by nearly 2 million units to a total sales volume of 12.3 million units, which alone accounted for roughly half of the 3.6% growth in GNP that year.

According to the consensus outlook, the change in auto sales in 1991 is expected to be far smaller and its subsequent impact on GNP growth, while still important, will be far less dramatic than in 1983. In fact, the median forecast of the group showed a modest drop in car sales from 9.5 million units in 1990 to 9.2 million units in 1991. Thus, even with sales in the second half of the year stronger than the first half, the contribution of auto sales to GNP growth in any given quarter will be modest. On this basis alone, the rebound in the second half of 1991 can reasonably be expected to be minimal.

Other types of consumer durable goods are unlikely to offset the weak auto market. Appliance sales have been weak for some time, in part because housing starts have been weak. Housing starts have been particularly weak among multifamily units, which were overbuilt during the early 1980s as a result of favorable tax laws. After changes in the 1986 tax laws, housing starts began to decline, reaching an unimpressive 1.21 million units in 1990, compared to an average 1.5 million-unit rate in 1984-85. For 1991, the consensus predicts only 1.17 million starts, which offers little stimulus to appliance sales. In addition, many appliances with once rapidly growing markets, such as microwave ovens, have reached their saturation points. Thus, much of the market for appliances will have to come from either replacement or remodeling. Factory sales of appliances declined throughout 1990, reaching their weakest point in the fourth quarter of 1990. According to an industry economist at the meeting, sales are expected to decline between 3% and 5% (annualized) in the first half of 1991 and turn positive (between 2-2.5%) only in the second half of the year.

While underlying conditions were unfavorable to growth in both the case of autos and appliances throughout most of 1990, it was the unanticipated Middle East crisis that produced the severe weakness at year’s end. In the past, declines in consumer confidence of the magnitude that occurred late in 1990 have always been followed by a recession, according to one presentation based on the University of Michigan’s indexes of consumer confidence. So, while it was true that the economy was sluggish before August, it appears that the scales were finally tipped in the direction of recession when the uncertainty about war caused consumers to spend cautiously during and after the Christmas selling season.

Can capital spending pick up the slack?

The erosion of confidence has not been limited to consumers. Businesses also appear to have become increasingly apprehensive about committing their scarce financial resources to capital spending programs in an atmosphere of uncertainty and a softening economy. In the consensus outlook, investment is expected to decline 1.3% in 1991, compared to a 1.4% gain in 1990. The weakest quarter is expected to occur at the beginning of the year. Investment is not expected to pull the economy again until the last quarter of 1991 and then is expected to provide only a minimal boost to economic activity. Typically, capital spending (particularly in equipment) is a major contributor to GNP growth in the early quarters of a recovery. But a recurring view at the symposium was that businesses were apprehensive about making capital spending decisions in the current economic environment.

The Commerce Department’s survey of plant and equipment spending plans for 1991 generally reflects that sense of apprehension. The latest survey was taken in October and November, but the results were released a week after the December 12 symposium and consequently were not available to the participants in the forecasting exercise. The survey results indicated that in 1991 businesses expect a meager 0.4% gain in constant dollar capital spending, compared with the 4.1% increase in 1990—marking the lowest growth in capital spending since the tax law-induced slump in 1986.

The weakness in investment seems to be widespread among capital goods producers. According to industry economists at the December symposium, both heavy equipment and farm equipment sales are expected to decline 5% in 1991, in part because of expectations of weak cash flow.4 Neither segment of equipment spending was robust in 1990. However, the decline expected in 1991 is closer to the early 1986 decline than to the steeper decline of past recessions. Other capital-goods producers at the symposium reported declining orders and, although the bottom had not dropped out of the market, several producers expressed concern about the market’s outlook for 1991. Even the office and computer equipment segment—currently about one-third of equipment spending and by far the major source of growth in recent years—is expected to decline about 2% in 1991, according to a supplier of parts to that segment.

Similar to appliances, the computer market is being now being driven by “add ons.” Decisions to add peripheral equipment to existing computer systems can easily be postponed in times of uncertainty.

Pulling out may be slow

The prospects for a short and shallow recession may have diminished with the employment and industrial production data released shortly after the December meeting, but the fundamental problems facing the economy have changed little. Durable goods markets are weak, having been dampened by weak profits and widespread uncertainty about the outcome of the Middle East crisis. The reason most often cited at the symposium for a mild and brief contraction was that the economy lacked the serious imbalances that caused the sharp and extensive contractions characteristic of past recessions. Moreover, the softness in the economy has triggered an easing in monetary policy. In fact, interest rates have been declining for some time, particularly the federal funds rate. And at the end of 1990, the discount rate was lowered for the first time since 1986. Given the normal lags in the economy’s response to a change in monetary policy, the second half of 1991 continues to be the most likely time to expect to see an expanding economy.

Perhaps the most serious risk to the 1991 outlook expressed by participants at the symposium is the willingness and ability of the financial system to fund consumption and capital spending in 1991. As pointed out by a financial economist at the symposium, many of the economic excesses of the 1980s were in the financial sector, led by highly leveraged buyouts of corporations. That fact makes traditional indicators of future business cycle movements, such as inventory-to-sales ratios, less relevant today and makes debt burden measures more relevant. And yet, according to several financial analysts at the symposium, the financial sector is inhibited by the same problem that is constraining the consumer and producer sectors—a pervading sense of uncertainty about the future. A resolution of the uncertainty that has dampened consumer and business confidence in the future may do more to pull the economy out of its current downturn than changes in either monetary or fiscal policies.

Notes

1 A summary of last year’s outlook can be found in the February 1990 Chicago Fed Letter.

2 The reader should be aware that data on November employment and industrial production, both widely perceived as very negative news, were not available until shortly after the symposium. While many lowered their forecasts for fourth quarter of 1990 and the early part of 1991, most of the group have since reported that their basic outlook for 1991 was little changed by the data released at the end of last year.

3 For a recent analysis of channels of monetary policy, see “The transmission channels of monetary policy: how have they changed?” in the December 1990 issue of the Federal Reserve Bulletin.

4 For a discussion of the effect of cash flow on investment, see Peterson and Strauss, “The cyclicality of cash flow and investment in U.S. manufacturing,” Economic Perspectives, January/February 1991, pp.9-19.