The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Note: The URL referenced throughout this Chicago Fed Letter, www.chicagofed.org/unbanked/, is no longer live on the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago website.

For 35 years the Chicago Fed has brought together practitioners and researchers to successfully address some of the toughest problems facing the financial services industry—through its annual Bank Structure Conference. The key to the conference’s success has been the Chicago Fed’s strategy of creating venues for business practitioners, policymakers, and academics to interact. The conference’s success stems from the value unlocked when representatives from these groups come together to focus on issues concerning the banking industry.

Now the Chicago Fed is taking that strategy to the internet, making possible year-round initiatives to address the most pressing concerns of the industry. In September 2000, the Chicago Fed, with cooperation from the U.S. Department of the Treasury, launched a new website, www.chicagofed.org/unbanked/. The site aims to provide a forum for research on issues relating to the unbanked segment of the U.S. population, i.e., those who do not use mainstream financial services.

The Fed’s experience with the Bank Structure Conference shows that publicizing research promotes research. Drawing on this experience, the Bank intends the new website to provide one place where bankers can obtain the information they need to develop banking services for this nontraditional customer base. The site is also intended to encourage academic research in this area. Researchers at the Chicago Fed have learned that the focus of academic research can benefit from close interaction between academics and members of the banking industry.

In this Chicago Fed Letter, I outline the Chicago Fed’s strategy for addressing issues relating to the unbanked via the internet.1 Below, I provide some background on the unbanked population. I then describe what has been done to date and how the Bank’s new website contributes to the effort.

The Unbanked?

Simply put, the unbanked are those who are not using the financial services that are used by the majority of the population. Estimates of the size of the unbanked population range from the five million recipients of federal benefits who do not have bank accounts (which would translate to 1.5% of the U.S. population) to 10% of the population. Why should we be concerned that individuals choose, for various reasons, not to use formal financial services? There are two main consequences from nonuse that are of concern to policymakers and industry observers. First, it is costly to deliver government benefits to recipients outside of mainstream payments channels. It simply costs more to deliver social security, veteran, and other benefits when the payment must be delivered via a check rather than an electronic transfer. The added cost is not trivial. Rates paid by the U.S. Treasury per individual transaction are 42 cents for payments by check and 2 cents for electronically delivered payments. Treasury estimates it can save $100 million per year by delivering federal benefits electronically.2

The second consequence of obtaining financial services outside of mainstream channels is higher costs for households. These costs include higher fees for completing transactions, a loss of personal security, and less effective participation in the economy.

The first of the costs for unbanked households is transaction fees. Most participants in the economy accomplish their payments via transfers between deposit accounts. Households receive income in the form of electronic transfers to their accounts or paper checks that can be deposited to accounts. These households then pay monthly bills from these accounts using similar payment mechanisms. By and large, the accounts used by households are provided by banks and other depository institutions. The costs institutions incur to provide these services are generally higher than the charges they levy on account holders. What makes the arrangement work is the income banks derive from the use of funds that households leave on account. Bank costs are also reduced because the scale of operation for their payment services is so large.

It is important to understand that participants in the mainstream of the financial system derive considerable benefit from their use of excess balances and from scale economies. Absent the ability to use funds left on account, the operating costs incurred by check cashers providing payment services must be covered by service fees for individual transactions. In addition, because the customers of a check cashing operation are far fewer, the operating scale is not present. These two factors imply that the payment services offered by check cashing operations are considerably more expensive than similar services offered by banks.

Transaction fees are higher for other reasons as well. The very large customer base seeking banking services attracts numerous entrants to the payment services business. Competition among these participants ensures that households shopping for payment service providers can expect to obtain good value for money spent. Absent this large market share, financial access is limited to a few providers and, therefore, is much more susceptible to less competitive pricing. In addition, the check cashing industry points out that it incurs higher costs of fraudulent presentations than do mainstream depository institutions. As the costs of fraud are much more easily understood than some of the other costs outlined above, it is not surprising that most explanations for the high cost of check cashing operations emphasize fraud. Although anecdotes may suggest otherwise, it is entirely possible that the other costs cited above may be more significant for check cashing operations than the costs associated with fraud.

When combined, Treasury notes these factors result in significant costs. The average 3% fee charged by check cashers for payroll checks produces a per month cost of $15 to $30. The average charge applied to social security checks ranges from $9 to $16 per month. Treasury estimates the average lifetime impact of all such charges for low- and moderate-income individuals at $15,000.3

The second cost unbanked households face is a loss of security. There is only one term of exchange for transactions outside the mainstream financial services arena: cash. With no place to store balances, individuals necessarily keep and carry large portions of their wealth in cash. This implies that these households cannot benefit from protections such as the $50 limit of liability from fraudulent use of a person’s credit card or from daily limits on ATM withdrawals. Because of the availability of such protections, the majority of the population can protect a much larger fraction of its wealth by simply using protected payments mechanisms rather than cash. Treasury estimates that U.S. households can reduce their annual losses from crime by $100 million by switching from a paper-based to an electronic payment mechanism.4

The third cost incurred by unbanked households is one of mindset. To succeed in today’s business world, one needs to be familiar with fundamental concepts such as credits and debits and to be able to critically review invoices and billings. Households limited to cash transactions have fewer opportunities to gain experience in these matters and, as a result, are less likely to develop the mindset needed to succeed in the workplace. Such practices deter individuals from extracting the full value of their labor, discourage efforts that will develop their skills, and, consequently, make those skills less available to the rest of the economy.

What is being done?

A number of efforts are underway to bring the unbanked into the mainstream of financial services. In June 1999, the U.S. Treasury introduced its ETASM product (electronic transfer account). This effort gives the recipients of payments from federal benefits programs a banking account, enabling beneficiaries to receive payments via electronic transfer rather than postal delivery of paper checks. Given an estimated five million recipients of federal benefits in the U.S., the complete success of the ETA program would result in a significant decline in the cost that Treasury incurs in delivering benefits—the cost savings would be more than enough to cover the operating costs of the ETA program. Working with Treasury are over 600 financial institutions at 9,500 branch locations that have agreed to provide ETA accounts in their communities. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas plays a key role in the development and operation of the ETA system.

The Federal Reserve has also stepped up its educational efforts. Most recently, the Chicago Fed initiated a financial literacy project. This is a major educational effort aimed at improving the population’s level of understanding of fundamental financial concepts—concepts that lead to successful planning for households and small businesses. In tandem with this Chicago Fed effort, Treasury recently announced a new grant program, FirstAccounts, for the development of educational resources that will raise the level of financial expertise in targeted populations.

In addition to these efforts at the federal level, states and community groups are paying increased attention to the problems of the unbanked. Illinois is now in the fourth year of operating its Link program, making food stamp and other welfare benefits accessible through a debit card. Other states are taking similar steps, moving toward using debit card or stored-value card systems and moving away from systems that rely on paper. Community groups are working with the states to educate the users of these new systems, as well as acting as advocates for improving the systems.

In addition to the ETA program described above, a number of banks are finding that establishing deposit relationships among this nontraditional banking population can be very profitable. The successes of Banco Popular, a relatively new entrant in the Midwest financial services arena, are often featured in the financial press. Bank One, working with the Woodstock Institute, has begun offering accounts designed to meet the needs of the unbanked population.5

Can we do better?

Developers of new and existing banking programs need to know what is going on—what has worked; what hasn’t worked. The Chicago Fed has now made it possible for any interested party to tap into such information. The Chicago Fed’s unbanked website allows developers to access information about the successes and failures of these programs and to obtain informed opinions regarding these outcomes. Previously, this information has been obtained at very high cost. Organizations have largely relied on individuals building networks of contacts by attending conferences and other informal channels. Michael Stegman of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill produced a book summarizing developments as of 1999. The book describes the state of the literature and offers an excellent and much needed reference section for those new to this field.6

While these information sources are extremely useful, researchers at the Chicago Fed believe that the scope of this problem requires a faster-paced, better-coordinated approach to information gathering. This prompted the Bank to begin working with Treasury to develop and operate a clearinghouse for information that will improve the rate of progress. The website gives a single point for information about these efforts. By lowering the cost of staying on top of developments, individuals working in these areas can devote more attention to developing banking services. In addition, information about successes and failures improves the profitability of their efforts.

The Chicago Fed also hopes the website will help focus the interests of researchers. The success of Mr. Stegman’s book signifies that there are outlets for publishing interesting findings in this area. The website offers a central source for timely information that can improve the relevance of research efforts.

The unbanked website features five sections, including an annotated and searchable bibliography. By continually adding bibliographic entries, the site provides a consistently up-to-date look at the body of literature that is used by practitioners, policymakers, and academics. Bank staff are now more than halfway toward their goal of completing a plain-language abstract describing each entry. The abstracts are prepared for a wide audience. Rather than replicating the financial jargon that is standard fare in academic publications, these abstracts use nontechnical language to present the examined issues and the results obtained. Where available, the entries provide an internet link to the document, making it immediately accessible to the researcher. A search engine is available to locate documents using a variety of terms. For example, the search term “check” presently locates two dozen references from the current database of bibliographical entries (there are over 300 entries as of this date). Six of the entries located in this example are abstracted and eight have links making them available online. Chicago Fed researchers continue to work to make the formal body of the relevant literature as accessible as possible for both interested academics and practitioners.

Other sections of the website also contribute to the information needs of this user community. One area provides links and information on the data sources needed to address research questions. Another section provides information on upcoming conferences where researchers can present research papers to obtain feedback from interested parties. The What’s New section will feature frequent updates on pilot banking programs and demonstration projects.

Of course, a website of this sort is never finished—it is always a work in progress. The Bank’s efforts over the next year will be directed toward two activities. First, Bank staff will focus on improving the content of the existing sections, while continually reviewing areas where unmet needs have been identified. Toward this end, the website lists an email address to which users can forward suggestions to improve the features, usefulness, and navigability of the site. Second, over the course of 2001, the Bank will introduce the website to target audiences that should find it useful—namely banking organizations, policymakers, academics, and the various state and federal bank regulators.

Conclusion

In summary, the new website on issues relating to the unbanked should lower the cost of conducting research by accelerating the information-gathering process. The resulting research may be expected to benefit the unbanked population. This effort fits well with the Chicago Fed’s strategy of promoting research that addresses the needs and interests of academics, businesspeople, and the broader community.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1992=100)

| November | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFMMI | 170.4 | 172.4 | 161.5 |

| IP | 154.4 | 155.1 | 147.5 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| December | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cars | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.6 |

| Light trucks | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.9 |

Purchasing managers' surveys: net % reporting production growth

| December | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW |

42.6 |

44.1 | 58.1 |

| U.S. | 42.4 | 49.6 | 59.0 |

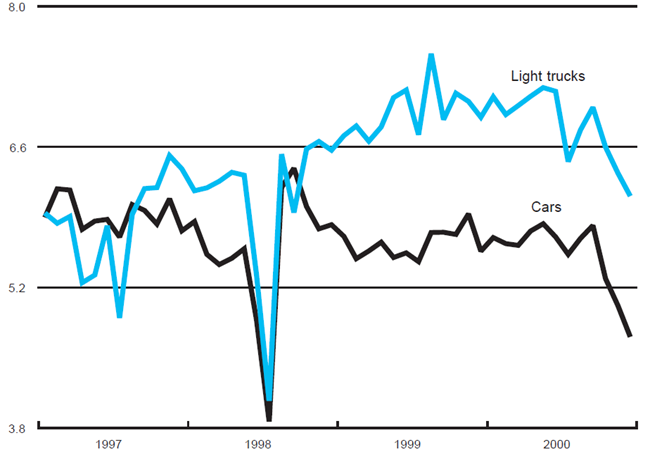

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

Auto production decreased from 5 million units in November to 4.7 million units in December. Light truck production also decreased from 6.3 million units in November to 6.1 million units in December.

The Chicago Fed Midwest Manufacturing Index (CFMMI) fell 1.1% from October to November, reaching a seasonally adjusted level of 170.4 (1992=100); revised data show the index was at 172.4 in October. The Federal Reserve Board’s Industrial Production Index for manufacturing (IP) declined 0.5% in November. The Midwest purchasing managers’ composite index (a weighted average of the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee surveys) for production decreased to 42.6% in December from 44.1% in November. The purchasing managers’ index decreased in Detroit and Milwaukee but increased in Chicago. The national purchasing manager’s survey also decreased from 49.6% to 42.4% during this period.

Notes

1 This article benefited from the comments of Bill Testa, Helen Koshy, Curt Hunter, Robert Feil, and the members of the working group. The website is the product of a working group who believe in making a difference. Chicago Fed working group members are: Tom Ciesielski, Joan Coogan, Melanie Ehrhart, Helen Lee, Katherine Miller, Genny Pham-Kanter, Sherrie Rhine, Jim Rudny, Tim Schilling, Dan Sullivan, and Lorrie Woos. Members from the Treasury Department are Roger Bezdek and Alan Berube. These people put in the time and effort needed to make this grassroots effort succeed. Their efforts were supported by senior management of the Chicago Fed, but especially by Bill Conrad, whose observation that “we can help these people” started it all.

2 U.S. Treasury Department, various press releases and speeches obtained from www.treas.gov.

3 U.S. Treasury Department, various press releases and speeches obtained from www.treas.gov.

4 U.S. Treasury Department, various press releases and speeches obtained from www.treas.gov.

5 Marva Williams, 2000, “Community-bank partnerships creating opportunities for the unbanked,” Reinvestment Alert, Chicago: Woodstock Institute, June.

6 Michael A. Stegman, 1999, Savings for the Poor: The Hidden Benefits of Electronic Banking, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.