The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

Against the backdrop of the current economic expansion entering its ninth year, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago invited economists from business, academia, and government to attend an Economist Workshop on February 5, 1999, focusing on the outlook for the Midwest economy in 1999 and beyond.1 This Chicago Fed Letter summarizes the workshop presentations on the economic outlook for the Midwest region and its states in 1999.

The Midwest economy in the year ahead

The Midwest economy finished 1998 at a slightly slower growth pace than it had shown earlier in the year. Midwest employment had been rising by nearly 2% in the first half, then increased at a 1.5% rate in the second half. For the year, Midwest employment grew by 1.7%, 0.1 percentage points slower than in 1997, and lagged the nation’s employment growth for the third consecutive year. The nation’s employment base expanded 2.6% in 1998, although, like the Midwest, it experienced a slower pace of growth in the second half. The marked slowdown in the region’s employment growth three years ago coincided with its unemployment rate falling to 4.6% in early 1996. By January 1998, Midwest unemployment had broken the 4% barrier; it remained below 4% for the entire year, finishing at 3.7%.

The region’s share of national manufacturing jobs rose to just under 19%, up 1.4 percentage points from the beginning of the current expansion. While almost 15% of all jobs nationwide were in manufacturing, the share of total employment in manufacturing in the Midwest was just over 20%.

Several manufacturing industries in the Midwest faced great challenges during 1998. The Asian crisis put pressure on electronic equipment manufacturers, as computer chip prices fell sharply. Foreign steel producers sharply increased their exports, doubling the U.S. market share held by imported steel from 20% to 40%. This steel “dumping” caused severe cutbacks and layoffs among domestic steel producers and pushed several small firms into bankruptcy. In addition, low commodity prices lowered farm incomes and hurt demand for agricultural machinery.

The strong consumer spending that has supported the national economy has also been quite strong in the Midwest. High consumer confidence— supported by low interest rates, a strong stock market, and good home value appreciation—has generated a spectacular housing market and a fairly steady sales pace for light vehicles.

According to an economist from a major Chicago bank, economic conditions in the Midwest will remain relatively robust. One challenge the region faces is an increasingly tight labor market. However, this is helping to offset the difficulties associated with the downturn in the regional steel industry.

Housing market activity is expected to continue at record highs; the regional housing market skyrocketed in the last quarter of 1998. Refinancing activity was strong for most of 1998 and reached new highs in October and December. This economist expects to see consumer loan activity increase. There are trade-offs between refinance activity and credit usage, so as refinance activity begins to soften, the economist expects to see a pickup in credit card usage.

The blizzard that hit the Midwest over New Year caused some disruptions in production activity in January, particularly in the vehicle industry, but the industry is expected to recoup this lost production very quickly. While the vehicle industry is producing at astoundingly high levels, significant growth above this output level is not expected.

Midwest employment growth is forecast at 1.3% in 1999 and 1.1% in 2000. This is likely to be below the national level, as has been the case for the past several years, due to a shortage of labor in the region. The Midwest has not been experiencing a lot of migration of workers from other parts of the country. The unemployment rate for the Midwest states will likely fall from 3.7% in December 1998 to 3.5% by the end of 1999.

The outlook for Illinois

An economist from the Illinois state government noted that labor market conditions vary quite a bit across the state. In southern Illinois, at least six firms in the steel industry laid off a significant number of workers in the third and fourth quarters of 1998. With a continuing buildup of demand for labor in other areas of the state, the laid-off workers must decide whether it is worth moving or commuting great distances to obtain employment. It is not yet clear how this dynamic will play out.

how this dynamic will play out. For the past five years, Illinois’ unemployment rate has been below the nation’s—a situation that last occurred in the early 1970s. The economist pointed out that a commercially generated forecast shows state unemployment increasing to 4.7% during 1999. Employment growth in the state is expected to increase by 1.3% in 1999, underperforming national employment growth. The key employment sector that benefited from Illinois job growth in 1998 was financial services. This economist doesn’t expect that sector to show the same level of strength in 1999. The transportation sector also did well in 1998 (trucking and warehousing), in large part due to the strong consumer sector and the large number of new homes being built. The manufacturing sector had declining employment for the last five months of 1998 and is expected to continue to struggle in 1999.

The outlook for Iowa

A government economist from Iowa mentioned that the state’s recent election of a Democratic governor, following two Republican governors who each served about 15 years, was only one of the many changes underway in the state. One of the biggest issues that the state has to address is the financial markets’ impact on foreign purchases of Iowa’s products. Iowa’s economy is two-pronged, with very large shares of employment and income generated by agriculture and manufacturing. There is also a hybrid of manufacturing—farm machinery and equipment—that sells to agriculture. As a result, in the 1980s Iowa experienced a capital goods recession followed by an export-driven recession that was double-bottomed and lasted for six years. Farmland, which is a large equity holding of farmers, lost 66% of its value; and Iowa lost a third of its car dealerships and banks and half of its farm implement dealerships. Although Iowa has recovered, farmland values are still not as high as at the peak in 1980.

To what extent are falling commodity prices (especially hog prices) portending a repeat of the 1980s in Iowa? This economist noted that the structure of Iowa’s mainstay industries has undergone significant changes since the early 1980s. For example, between 1983 and 1997, the employment of the group that sells to agriculture dropped by 33%, representing employment cutbacks by John Deere, Massey Ferguson, and J.I. Case. While these companies have reduced employment, they are producing more, due to the use of robotics and just-in-time inventory systems. Although this industry is the most volatile in the state, driven by changes in agriculture, it currently has the ability to weather a sustained downturn. The large inventories that farm implement dealers all over the state had in 1983 are long gone. Customers buy their equipment from catalogs, and only used equipment sits in the fields. The industry’s inventory-to-sales ratio has fallen from over 4.5:1 in 1983 to 1:1 currently.

The chemical sector has diversified, expanding its production from mostly agricultural chemicals to pharmaceuticals and agricultural byproducts, such as lysine, and corn and soybean derivatives for nonagricultural purposes.

The sector that buys from agriculture has shown the most growth in Iowa compared to the rest of the nation. This is a sector that Iowa would like to develop even more. While Iowa is being undersold in the grain markets by countries that it used to sell to, such as China and Argentina, it can take advantage of opportunities in value-added products, e.g., by exporting corn syrup instead of corn and tofu instead of soybeans. Nonetheless, this economist expects a large number of people to leave agriculture, coupled with a loss of income in the agriculture sector over a sustained period.

Although farm incomes have declined, they remain at levels they have averaged over the past 15 years. Farmers made a large amount of capital goods purchases in 1997 and early 1998, and the agricultural equipment market is expected to remain weak during 1999 and 2000. However, this slowdown couldn’t happen at a better time given the employment situation. Unemployment rates in Iowa averaged 2.6% in 1998, the third year in a row of under 3% unemployment.

As Iowa continues to lose population in rural areas, more public capital expenditures may be shifted to the cities. However, unlike Minnesota, which has stopped trying to hold back the tide of population outflow from rural areas, Iowa has attempted to retain population in rural areas. Iowa has one of the oldest state populations in the nation and it probably won’t be too long before deaths exceed births.

Housing construction is expected to slow somewhat in 1999, largely due to a labor shortage. In 1998, building permits growth reached an all-time high of 39%, supported by low mortgage rates.

With the lowest unemployment rates in the region, Iowa’s employment growth is forecast to be just 0.5% in 1999 and 0.25% in 2000. Nominal income, which grew at 3.8% during 1998, is expected to increase to 6.25% for both 1999 and 2000.

The outlook for Indiana

A university economist presented the outlook for the Indiana economy. While the Indiana economy continued to operate at relatively high output levels with the second lowest unemployment rate in the region, employment is only expected to grow by 1% for 1999. Personal income in Indiana is anticipated to grow at a very slow 1.5% this year.

The manufacturing sector is very important to the Indiana economy. The state has the highest concentration of manufacturing workers in the region, accounting for over 23% of the state’s total workforce. Manufacturing in general finished 1998 on a weaker note than it began, and the domestic steel sector could be categorized as being in a recession. The problems facing the steel industry affect Indiana more than any other state in the region, since Indiana produces roughly 25% of all the steel produced in the U.S.

The state has been struggling to maintain its relative economic position over the past 20 years. Compared to the nation, Indiana has continuously lost share of output and population over this period, with the only exception being the early 1990s, when it picked up relative to the nation (largely because California was doing so poorly at that time).

This economist felt that, to a large extent, the housing market boom can be attributed to a phenomenon referred to as climax housing. People are building or buying the house that represents the peak house that they are going to own. Some are even buying into larger houses than necessary and viewing it as an investment. Given the low mortgage rates, it is believed that more consumers are viewing purchasing a house as a way of diversifying their investment portfolios.

The outlook for Michigan

An economist from the Michigan state government analyzed the state of the Michigan economy. The vehicle industry continues to be very important for Michigan. Vehicle ownership per household continued to grow in 1998. Light truck sales are approaching 50% of total light vehicle (cars and light trucks) market sales. Consumers love trucks. With low gasoline prices, image improvement for trucks, and high residual values, the purchasing trend toward trucks will likely continue in 1999. The pricing environment for vehicles remains very competitive. New vehicle sales continue to be quite impressive, especially this late in an expansion. December 1998 new vehicle sales were the strongest monthly sales in over 12 years. New vehicle sales have been above trend since 1994. With the anticipated slower gross domestic product growth in 1999, vehicles sales are also expected to moderate in 1999 to average 15 million units, and then hold steady at that sales level in 2000.

This slower pace of economic growth for Michigan will be reflected by a slowing in personal income growth from 3.9% in 1999 to 3.4% in 2000. Michigan’s unemployment rate is expected to remain relatively low, averaging 3.7% during 1999 and rising to 4.1% in 2000. Employment in Michigan is forecast to increase by 1.8% in 1999 and then rise by a slower 1.2% in 2000. Manufacturing employment growth is expected to increase by 0.2% in 1999 and then fall by 1.2% in 2000. Private nonmanufacturing job growth in Michigan is expected to increase by 2.6% in 1999 and slow to 2.1% in 2000.

The housing market has generally been very robust in Michigan. Although there are some weak pockets, even the city of Detroit, which had been very slow for a long time, has shown some significant gains in housing prices in the last few years.

Manufacturing employment has been losing its share of total employment in the state over the years. In 1969 manufacturing jobs represented a third of all workers, in 1977 it had fallen to 28%, and in 1997 it reached 19%. Most of the new employment opportunities are in small firms. Output is still considered pretty sensitive to national economic growth, but because of all the capital spending to improve productivity, changes in employment are probably not as sensitive to competitive pressure as in the past.

The outlook for Wisconsin

An economist from a manufacturing firm in Wisconsin presented the outlook for the Wisconsin economy. The Wisconsin economy continued to operate at full output levels in 1998. The tight labor markets have been a restraining factor on output growth. At this economist’s company, the blue-collar workforce has been very stable, but there has been more noticeable turnover among the white-collar workers. Observing that the parking lots at shopping malls continue to be full, this economist would have expected that this late in the expansion consumers would have purchased everything they wanted.

The outlook for the Wisconsin economy is for continued growth at slower rates than the rest of the nation, with labor markets remaining quite tight. This economist does expect a slight downturn in the economy within the next two years. The current expansion has gone on so long, this economist feels that a downturn is due to occur.

Conclusion

The outlook for the Midwest economy in 1999 is for slower growth than the rest of the nation, as the region struggles with tight labor markets. This has probably been the most restraining factor for growth in the Midwest. Full employment has been a bittersweet issue for the region. It has brought significant challenges for individual states, reflected by the economists’ presentations at the workshop, to ensure continued economic growth with such low unemployment rates. As the rest of the country continues to move toward the Midwest’s unemployment rates, this is a theme that most certainly will be echoed across the nation.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1992=100)

| January | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFMMI | 129.6 | 129.8 | 128.7 |

| IP | 136.7 | 136.6 | 133.8 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| February | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cars | 5.4 | 5.6 | 5.4 |

| Light trucks | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.3 |

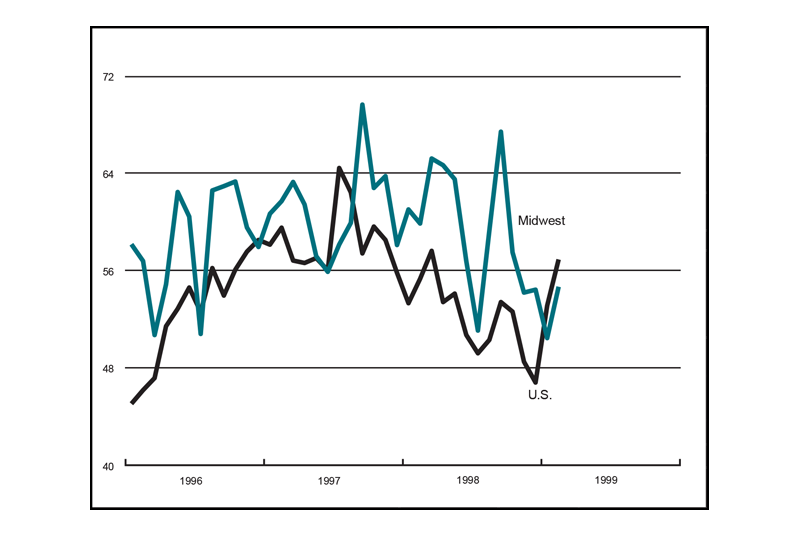

Purchasing managers' surveys: net % reporting production growth

| February | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 54.7 | 50.4 | 59.9 |

| U.S. | 56.9 | 53.1 | 55.3 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

The Chicago Fed Midwest Manufacturing Index (CFMMI) decreased 0.2% from December 1998 to January 1999. In comparison, the Federal Reserve Board’s Industrial Production Index for manufacturing (IP) increased 0.1% in January 1999 from December 1998. Light truck production increased slightly from 6.8 million units in January to 6.9 million units in February and car production declined from 5.6 million units in January to 5.4 million units in February.

The Midwest purchasing managers’ composite index (a weighted average of the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee surveys) for production increased to 54.7% in February from 50.4% in January. The purchasing managers’ index increased in all three surveys. The national purchasing managers’ survey for production also increased from 53.1% in January to 56.9% in February.

Notes

1 The workshop was organized by William Strauss, with valuable assistance from William A. Testa and Keith Motycka. The Midwest is defined as the states of the Seventh Federal Reserve District— Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin.