Our History

History

The Federal Reserve is a distinctly American central banking system—the product of a long and tumultuous history of compromise and collaboration. Unlike many of its contemporaries around the world, the Fed is decentralized, yet centralized; a public institution in service of the people, yet inextricably linked to the private sector. Through three different centuries of U.S. history and countless economic highs and lows, the novel and long-debated solution to the nation’s monetary problems has evolved, growing into the role envisioned for it—and re-envisioned, decade after decade.

The Chicago Fed shares in this history, innovating in service to the region it represents and the nation as a whole to meet the challenges of the day and prepare for the future.

Before the Fed

Two national bank charters preceded the current Federal Reserve System. The first was championed by Alexander Hamilton; the second vetoed on renewal by President Andrew Jackson. The First and Second National Banks took bank deposits and offered loans to citizens, while also acting as the government's bank, collecting taxes, paying its bills and granting its loans. Both bank charters were denied renewal after their inaugural 20-year periods over concerns that they had become too powerful.

Financial instability characterized the decades following the two failed charters, setting the stage for a third push for a national bank at the turn of the century. The panic of 1907 saw a nationwide run on banks, only halted by significant monetary contributions from J.P. Morgan and other private entities. The U.S. banking system was proven unequipped to meet the financial needs of the country.

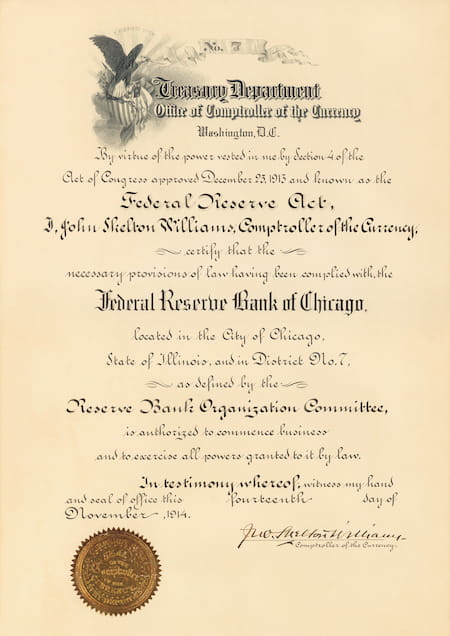

In 1908, Congress tasked the National Monetary Commission with assessing the monetary state of the nation in the wake of the 1907 panic. 30 reports later, the Commission ultimately proposed the establishment of a national reserve association in 1912. The idea was initially rejected by Congress, but it wasn’t abandoned altogether. Another proposal for a central banking system by Representative Carter Glass of Virginia and Parker Willis, a former economics professor who served as advisor to the House Committee on Banking and Finance, was enough to win over the U.S. legislative body. After months of effort and compromise, the Federal Reserve Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913.

For the third time, the U.S. had a central bank—this time with a central board to oversee it.

The Chicago Fed is Born

An organizational committee toured the nation soon after, tasked with deciding the number of Reserve Banks (no more than 12, no fewer than eight), their locations, and their surrounding districts of service. Chicago was named the seventh of 12 Reserve Banks, its territory including northern Illinois and Indiana, southern Wisconsin, all of Iowa and the lower peninsula of Michigan. Banks in 25 northern Wisconsin counties would later petition to be added to the Seventh District, a request granted by the Federal Reserve Board in 1916.

Member banks elected six of the Chicago Fed’s nine directors. The other three were appointed by the Federal Reserve Board. The directors selected James B. McDougal as the Chicago Fed’s first governor, a title later changed to President in 1935. With leadership and organization in place, the Bank opened alongside the other 11 Fed banks on Monday, November 16, 1914.

Leading the Way

Initial currency and rediscounting operations were steady, but slow. With authority drawn from the other services category of the Federal Reserve Act’s preamble, the Bank worked to develop an intra-district check collection and clearing service with no required exchange fee, known as accepting at par. This system was offered to district banks on a voluntary basis in 1915, then made compulsory in 1916. By 1922, every bank in the District accepted at par, and the Bank processed over 60 million checks annually.

When the U.S. declared war on Germany and joined the First World War in April 1917, the Reserve Banks were authorized to handle the financial operations associated with the war. This included the sale of Liberty Bonds. After increasing personnel to handle the campaign, the Bank sold $3.29 billion in bonds by the end of the war, the largest subscription per person in any of the Federal Reserve Districts.

Statistical data on business trends became increasingly available in the early 20th century, and the Chicago Fed pioneered efforts taken on by the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC and the Fed Banks to sort and analyze it. The Bank had already begun publishing Business Conditions, a monthly review of the Seventh District economy, in October 1917; in 1918, the Chicago Reserve Bank established the Statistical and Analytical Department to compile statistical information for the Federal Reserve Board and member banks. Over the next few years, the Chicago Fed began collecting a condensed statement of condition from selected member banks and started a Business Reporting Service that gathered data from producers and merchants.

In 1923, the Federal Reserve Board established the Federal Open Market Investment Committee, which was comprised of the governors of the Chicago Fed and four other Reserve Banks and instructed to monitor the state of national credit. Throughout the 1920s, the Federal Reserve moved toward increased centralization and coordination in monetary policy, as the concept of 12 regional credit policies based on the needs of each district slowly gave way to a coordinated policy with a national focus.

Moving Up and Out

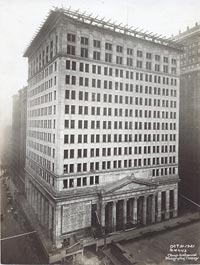

From 41 employees on opening day to 1,200 by 1919, the Bank had outgrown its office spaces—at the time scattered throughout the Loop in downtown Chicago. The Chicago Fed purchased a lot on LaSalle Street that extended from Quincy Street to Jackson Boulevard. The architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst and White (designers of the Continental Bank Building across the street from the Chicago Fed, the Wrigley Building, the Civic Opera and the Merchandise Mart) completed the landmark Beaux-Arts building in 1922.

Frustrated by business delays caused by travel time, Michigan bankers expressed the desire for a Branch of the Chicago Fed in Detroit. As the second largest industrial area in the Seventh District, Detroit was a logical candidate, and the Bank board of directors voted in November 1917 to establish the Branch.

The Great Depression

Historic levels of speculative spending led to a stock market crash on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. Economic conditions worsened internationally as England abandoned the gold standard in 1931, and the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to slow the flight of gold from the country, after having previously lowered rates after the crash of 1929.

Two dominant banks in Detroit faced collapse by February 1933. Chicago Fed Governor McDougal, leading commercial bankers, U.S. Treasury officials, representatives of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and others met to resolve the crisis, but no organization, public or private, was willing to provide the necessary loan. A statewide bank holiday declared by the governor of Michigan prompted an even greater currency drain on the Chicago Fed.

The nationwide economic panic peaked in March of 1933 as Franklin D. Roosevelt took presidential office. With provisions initially rejected by outgoing president Herbert Hoover, Roosevelt declared a four-day bank holiday on his first weekday in office, two days after his inauguration—Monday, March 6, 1933.

Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act on March 9, 1933—the final day of the bank holiday. Under the Act, banks were reviewed by regulators and licensed to reopen if they were solvent. If not, they remained closed. Bank closings reached 4,000 in 1933, approximately 30 percent located in the hard-hit Seventh District. The Fed was revealed to be unable to head off the very catastrophe it had been established to prevent.

In the Wake of the Depression

Congress began economic reform with the Glass-Steagall Act in June of 1933. The Act established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which provided the Fed with two new tools: the authority to change member banks' reserve requirements, and permanent authority to lend to member banks simply on the basis of satisfactory assets as opposed to only paper collateral. The Act further created the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to conduct the Federal Reserve System's open market operations. This committee, consisting of the Board and five Reserve Bank presidents, came to be the System's chief monetary policy-making body.

The U.S. was unable to fully shake off the Depression until preparations began for the Second World War. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Chicago Fed found itself once again responsible for coordinating the Seventh District's bond drives. The Chicago office of the Bank alone handled 50 million securities worth $24 billion, $3 billion more than the entire amount raised nationwide in the First World War.

In the interest of market stabilization, The Federal Reserve effectively pegged interest rates on Treasury securities and pledged to buy Treasury securities at a predetermined rate for the duration of the war. Upon its conclusion, the Fed discontinued these restrictions and, in accordance with the Treasury, gradually allowed bond prices and yields to seek their own level as dictated by overall credit requirements.

Post-War Growth

Throughout the 1950s, the Fed generally followed a policy aimed at moderating the severity and duration of cyclical readjustments, described by Federal Reserve Chairman William McChesney Martin as "leaning against the wind." Buoyed by a general policy of monetary and fiscal stimulus, the U.S. economy—and the Bank itself, after a 16-story addition—grew steadily through most of the 1950s and early 1960s.

Fueled by healthy agriculture and heavy industry sectors, the region nevertheless engaged in the nationwide practice of redlining. Redlining was a federal initiative intended to show risk areas for federal backing of home ownership programs, and was significantly informed by race, ethnicity, and immigration status. De facto discriminatory policies in areas like employment and education further excluded many residents from the region’s prosperity.

Growing Responsibilities

Interest rates continued to increase in the late 1960s, influenced in part by U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. By the end of the decade, approximately 74 percent of Seventh District banks were paying the 4 percent maximum rate for savings deposits, according to a 1969 Chicago Fed survey.

The end of the 1960s also saw the beginning of the Federal Reserve's responsibility for consumer credit regulation. In 1969, Congress passed the Truth in Lending Act, Title I of the Consumer Credit Protection Act. In 1977, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act, aimed at reducing discriminatory credit practices in low-income neighborhoods.

Higher and more volatile interest rates into the 1980s threatened the Federal Reserve’s ability to conduct monetary policy as member banks fled the System to avoid the burden of holding non-interest-bearing reserves. The 1980 Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (MCA) sought to enable more competition among financial institutions by phasing out deposit ceilings and authorizing negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts. The Act also imposed reserve requirements on all depository institutions, not just Federal Reserve member banks.

The MCA further required the Federal Reserve member banks to price many of their formerly free services and offer them to all depository institutions. The Banks joined a number of competitors in the marketplace, and this provision greatly increased the number of potential Federal Reserve customers, as well as institutions required to submit statistical data.

The MCA shortened check-clearing schedules, introduced new services, and maintained relatively low prices upon implementation. Automated Clearinghouse (ACH) usage, aided initially by price subsidies, increased substantially. The MCA also enabled the Fed Banks to encourage more efficient online wire transfers through price incentives and the availability of inexpensive computer equipment. "It produced a much leaner, more efficient, and, I think, more satisfying organization," First Vice President Daniel Doyle observed. "It's one thing to respond to internal standards, it's quite another thing to meet the standards of the marketplace. I think we were very successful."

Inflation

Inflation problems persisted into the 1970s, exacerbated by two oil price shocks, resulting in the worst inflation of the post-war period. After an emergency FOMC meeting on October 6, 1979, Chairman Paul Volcker announced that the Federal Reserve's monetary policy efforts would focus on reaching target levels of bank reserves through open market operations. A sharp increase in the entire spectrum of interest rates immediately followed, and the economy slowed in the 1980s.

In response, the Chicago Fed participated in cooperative economic development projects within the District, including studies of the Great Lakes region, the states of Iowa and Wisconsin, and the cities of Chicago and Detroit. Eventually, the national economy began to improve, reaching its peacetime record sixth year of uninterrupted growth in 1987. The Midwest lagged behind until that year, when its economic activity once again outpaced the rest of the nation for the first time since 1980.

Understanding the Past

Economic volatility and increased competition resulted in a dramatic increase in bank failures in the 1980s, especially agricultural and large money center banks in the Seventh District. A bank run was no longer necessarily a local phenomenon, and the potential for a worldwide electronic run presented new challenges for the Chicago Reserve Bank. Unlike 1933, however, the Federal Reserve and other regulators had the resources to help prevent a bank from closing if necessary.

After a rapid stock market plunge in 1987, the Fed responded by injecting liquidity into the financial system, emphasizing its willingness to lend to banks through the discount window, and extending the hours on FedWire, the Federal Reserve's large dollar transfer system. At the same time, each of the Reserve Banks intensified its monitoring activities to detect signs of further stress. At the Chicago Fed, Bank officials paid particular attention to developments at local exchanges.

In step with a changing financial system, the Chicago Fed’s supervision of banks and bank holding companies broadened in scope and detail. "Our view of banks became dramatically broader in the 70s and 80s," noted James Morrison, head of the Bank’s Supervision and Regulation Department during those two decades. “It's a much more complicated process, but we're also dealing with a much more complicated financial system."

Into the 21st Century

The period of general macroeconomic stability from the mid-1980s to 2007, dubbed the Great Moderation, was characterized by low, steady interest rates and the longest economic expansion since World War II. The Chicago Fed, along with the rest of the System, prepared its personnel and internal systems to handle the Y2K threat to automated processes throughout 1999.

These emergency protocols would prove even more useful than their original intent two years later. After the terror attacks on the Pentagon and Lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001, The Fed quickly provided liquidity to a reeling global financial system. The Fed also forgave penalties on double-counted uncashed checks, the extraordinary float caused in part by the grounding of the Fed's 12-plane fleet used to transport paper checks to Fed Branches for processing.

The Chicago Fed, one block from the Willis Tower, evacuated non-essential employees but remained in place for the duration of the crisis. Like many other Branches, Chicago employees worked long hours to assist customers and keep the discount window open until midnight for three days following 9/11.

The Great Recession

High-risk or subprime mortgage lending disrupted the Great Moderation in 2007. With home prices decreasing and mortgage defaults and foreclosures on the rise, the Fed provided support, including liquidity, to individual financial institutions facing collapse in the interest of stabilizing the national and global economies. The Fed also brought interest rates as low as effectively possible by the end of 2008.

Recovery started, albeit slowly, in June of 2009. Federal Reserve Banks began regular stress testing, running banks through worst-case scenarios and assessing preparedness. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act allowed for Systemically Important Financial Institutions to be overseen by the Fed, created the Orderly Liquidation Authority for the FDIC to safely deconstruct failing firms, and required large institutions to create detailed plans in case of failure, called living wills.

A Global Pandemic

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in response to the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid19). The global economy experienced a worldwide market crash between February and April 2020, the worst in U.S. history. On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared Covid-19 a global pandemic, and the Chicago Fed instituted a mandatory work-from-home situation effective the following day. The Federal Reserve announced plans to inject $1.5 trillion into money markets and greatly lower interest rates—both of which the Fed upheld and supplemented into 2021—but the nation continued into recession.

The Chicago Fed continues to conduct remote operations in 2022. The future of work is uncertain; what is clear, however, is the Fed’s continued commitment to meet, step by step, the challenges of the coming decades—with over 107 years of history, changing responsibility, and economic highs and lows in mind.