The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

A recent Chicago Fed conference brought policymakers and researchers together to discuss the nature and extent of economic linkages within the Great Lakes economy. Participants explored ways to balance the need for greater security along the U.S.–Canada border in the aftermath of September 11 with the desire to facilitate cross-border trade and employment.

On April 4 and 5, 2002, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago held a conference on the nature and extent of economic linkages within the Great Lakes economy, an area that encompasses parts of the U.S. and Canada, and related policy issues, such as border crossings, trade barriers, and immigration. The event took place at the Chicago Fed’s Detroit Branch, minutes away from the Detroit Tunnel and the Ambassador Bridge, the two busiest border crossings between the two countries.1 This Chicago Fed Letter summarizes the conference discussions.

In his opening remarks, William Testa, vice president and director of regional programs at the Chicago Fed, stated that the core idea of the conference was to take a fresh look at the economic relationship between two parts of the Midwest, a single region that overlies two countries: Canada and the U.S. Testa noted that much of the border that separates the Canadian from the American Midwest is defined by a physical barrier, the Great Lakes waterways. They once represented the speediest and least costly mode of transportation, bringing the two countries closer together and molding the region’s manufacturing and natural resource industries into the most tightly integrated in the world. It is therefore not without irony, he pointed out, that today we find ourselves grappling over issues of the adequacy of overland transportation infrastructure, roads and bridges, and whether we can squeeze more than U.S.$1 billion per day of international commerce through the few and narrow portals that span the lakes.

Testa encouraged participants not only to assess the importance of this binational regional relationship in its various aspects, ranging from commerce and its infrastructure to tourism, recreation, energy, and migration, but also to create a vision of how the relationship could progress. But first, Testa noted that, given the events of September 11, 2001, and the resulting security concerns, we need to examine current travel and trade policies and prospects for the free flow of goods and people across the border.

Keynote address

Speaker: Chris Sands, fellow and director of the Canada Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC

In the opening keynote address, Chris Sands put the current debate on border security in perspective.2 He provided a detailed timeline to illustrate that the 30-point “Smart Border Declaration” issued by the U.S. and Canada on December 12, 2001, resulted from thinking that started in February 1993 in response to that year’s World Trade Center bombing. He identified three strands in the debate since 1993 that underscore the reaction of the U.S. and Canadian governments to the September 11 attacks.

First, he cited congressional attempts to reform U.S. customs and immigration policies that resulted in the Customs Modernization Act of 19933 and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996.

Second, Sands discussed Canada’s attempts to engage the U.S. government in a bilateral dialogue on border management, which Canada hoped would divert the U.S. from implementing the Section 110 provision of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. This provision required the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to develop a system to document the entry and exit of non-U.S. citizens at all border crossing points. As a result of these efforts, the U.S. and Canada adopted the following joint agreements:

- The U.S.–Canada Shared Border Accord, signed February 1995, included a series of measures to improve the cooperation between customs and immigration officials in both countries.

- The Cross-Border Crime Forum, established in 1997, was created to encourage law enforcement agencies in both countries to work together more effectively to combat transnational crime.

- The CUSP (Canada–U.S. Partnership) Agreement in 1999 initiated a series of stakeholder consultations to solicit ideas and input on border management from communities, interest groups, and businesses.

- In November 2000, test implementation of a new electronic security system called NEXUS began at the Blue Water Bridge crossing between Sarnia, Ontario, and Port Huron, Michigan. Under this program, U.S. Customs, the INS, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, and Canada Customs developed a common data form, allowing travelers and shippers in both countries to file the same personal information to apply for designation as a low-risk traveler. It facilitates the land border crossings of those who have previously registered to allow a greater focus on those not identified as low risk. The program was suspended in wake of the September 11 attacks. Current plans see it being rolled out by summer of 2002 at three ports of entry along the British Columbia / Washington State border and by the end of this year at high-volume border crossings in Southern Ontario, New York State, and Michigan.4

Third, Sands cited the growing penetration of both societies by Al Qaeda terrorists that culminated in the September 11 attacks. The 30-point Smart Border Declaration was endorsed on December 12, 2001, by the governments of the U.S. and Canada. In it, both governments pledge to improve cooperation, develop new joint procedures, share more intelligence information, and implement specific reforms to immigration, inspection, and traffic management practices at the border. Sands characterized it as a complex and ambitious agenda but suggested that it represents not a new beginning so much as a new commitment of political will and adequate funding to follow through on good ideas that had languished for want of both prior to September 11.

Looking ahead, Sands raised the question whether the Smart Border Declaration can succeed in improving the security and efficiency of the Canada–U.S. border while decisively forestalling measures like Section 110, where previous efforts have met with only partial success. Sands outlined the following lessons from the debate since 1993 that both countries should bear in mind in implementing the Smart Border Declaration. From the U.S. perspective, there are several points: Security cannot ignore economic concerns; underfunded mandates rarely succeed; the border to Mexico and the border to Canada are characterized by very different issues; and, finally, unilateral decisions on border issues ultimately make things harder. His lessons for Canada were as follows: Economic concerns don’t trump security concerns; there is a need to close the credibility gap with the U.S. on security issues; tri-lateral solutions are problematic for Canada, but tempting for the U.S.; and, finally, participation in the U.S. domestic debate is open to the Canadian government and its domestic critics. In conclusion, Sands noted that since September 11 a reasonable balance between economics and security has been struck. In particular, he pointed to the improved funding situation on security issues and suggested that the U.S. and Canada have rediscovered that there is room for bilateral policy on border issues.

Impact of September 11—The border becomes visible

Presenters: Phil Ventura, assistant deputy minister in Canada’s Privy Council Office; Ken Swab, legislative director, Office of Congressman John J. LaFalce; James “Jim” Phillips, president and chief executive officer, Canadian/ American Border Trade Alliance

Sands’ speech was followed by a panel discussion on border security issues. Phil Ventura started out by referring to the region of southwestern Ontario and southern Michigan as one large manufacturing assembly system. The role of the border in this very highly integrated region changed dramatically on September 11, 2001, from a mere nuisance to a potential stranglehold, owing to significantly heightened activity between the U.S. and Canadian governments to address national security issues. The ongoing challenge in this effort, he argued, is to come up with security solutions and procedures that do not make this region vulnerable and dysfunctional on the economic side. Ventura went on to outline the strategy of the Canadian government for dealing with border security issues. Canada established a cabinet-level committee that is being chaired by Deputy Prime Minister John Manley. The principal approach of this effort is reflected in the Smart Border Declaration. The operational concept is to apply risk management to border security, i.e., to implement policies and procedures that help separate high-risk people and goods from low-risk people and goods. Such an approach will allow a more efficient use of resources at the border. Since September 11, Ventura added, Canada has significantly stepped up its funding of border security, committing an additional $7.7 billion Canadian dollars over the next five years. Canada issued new permanent resident cards at the end of January 2002. The visa policies between the U.S. and Canada are now being coordinated. Furthermore, there is the possibility of establishing pre-clearance centers to improve efficiency at the actual border crossings. The NEXUS program, currently suspended after its initial test, will be rolled out on the West Coast in June, with a tight timetable to extend it for the entire border. Ventura concluded by arguing that a successful approach to border security issues needs to include monitoring of the actual implementation of new security measures, as well as keeping a long-term perspective on their efficacy.

In providing a perspective from Congress, Ken Swab referred to the Northern Border Caucus, established by Congressman LaFalce after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993 to pursue policies that facilitate the movement of commerce and people, as well as providing secure borders. He noted that all the September 11 terrorists had entered the U.S. directly and legally; none had entered from Canada—something to keep in mind in addressing security issues at the northern border. He also noted that in the U.S. border resources have traditionally been focused on the border to Mexico. This is starting to shift. Swab praised the ideas in the Smart Border Declaration and discussed the additional resources that have been directed to the U.S.–Canada border since September 11. In 2002, 716 personnel have been added to the northern border, with another 114 planned for 2003. Congress has authorized a tripling of northern border staff, but appropriations appear to be short of that level. However, more than people are needed. Also key to expediting the flow of goods and people is new technology, such as a long overdue new computer system (Automated Commercial Environment, or ACE), which is to be implemented by fall 2005. The budget for that system, however, remains underfunded.

Next, Jim Phillips represented the views of a broad-based binational business organization, whose member businesses are closely tied to a well-functioning U.S.–Canada border. Phillips pointed out that U.S.—Canada trade is greater than trade between the U.S. and the entire European Union. U.S. trade with Ontario is essentially equal to U.S. trade with Japan. Most goods are carried across the border by trucks, using the land border crossing gateways and highway corridor infrastructure. Concurring with earlier presenters, Phillips reiterated that, historically, the northern border had been underfunded. Additional resources that are being made available under the U.S. Patriot Act are encouraging, he said. He strongly recommended the implementation of a joint U.S.–Canadian low-risk traveler technology system, such as NEXUS, to allow participating U.S. and Canadian citizens to enter either country via dedicated lanes. Finally, he addressed the existing infrastructure limitations at the actual border crossings by presenting simulation results commissioned by a group called the Perimeter Clearance Commission. Using the Buffalo Peace Bridge crossing between the U.S. and Canada as an example, this study shows how the efficiency of an existing border crossing can be improved significantly without costly infrastructure changes. By moving three U.S. Customs primary inspection booths from the U.S. to the Canadian side, as well as introducing the NEXUS system, one could realize substantial improvements in waiting and processing time at the border crossing. However, Phillips pointed out that even with improvements like these, the existing border crossing infrastructure will not be able to meet expected growth in trade during the next five to ten years.

Keynote address

Speaker: Peter McPherson, president, Michigan State University

Peter McPherson opened the second day of the conference with a keynote address on the region’s economic linkages. He briefly illustrated the magnitude of the trade relationship between the two countries. U.S. trade with Canada is 50% larger than that with the U.S.’s next largest trading partner, Japan. Canada buys almost 25% of all U.S. exports. McPherson stated that the region enjoys a mature trade structure. Since 1989, when the U.S.–Canada Free Trade Agreement (FTA) went into effect, trade between the two countries has grown by 10% per year. This is particularly significant for Michigan, with 58% of its exports going to Canada. As we might expect, over 75% of the trade between Michigan and Canada is in transportation products.

McPherson recalled the short-term disruption to border traffic caused by the events of September 11. As an immediate reaction, security concerns replaced the flow of trade as the top priority. Consequently, commercial and passenger traffic volumes were down drastically during the first week after the terrorist attacks. Since then, border traffic has reverted to more normal levels. In looking ahead, McPherson focused on policy objectives for the medium as well as long term. He suggested a smart border approach for the U.S. and Canada, along the lines of what was proposed in the December 2001 Smart Border Declaration. This would encourage innovative border procedures instead of concentrating resources at the immediate border, which slows down the movement of goods and people. A smart border approach involves enhanced coordination, information exchange, and resource sharing. Common technology and recordkeeping standards would be used under such an approach to facilitate information exchange. For the longer run, McPherson suggested working toward formalizing a “zone of confidence” to enhance both security and trade. He argued for less emphasis on the 4,000-mile border between the U.S. and Canada. Instead, he suggested building on the long history of cooperation between the two countries, which has established a de facto Canadian–U.S. zone of confidence. McPherson strongly recommended building on the zone of confidence that already exists and synchronizing laws and regulations to that effect. With such a zone, for example, Canada and the U.S. could achieve a level of security that works for both countries without having to adopt uniform immigration and asylum policies.

In addition, McPherson addressed the question of how to improve the trade relationship between the two countries. He argued that despite the success of the FTA and NAFTA, there still exist a number of trade barriers that should be removed. He specifically mentioned government procurement rules, trade in services, and rules of origin, which result in tariffs on goods from a third country that are subsequently shipped across the U.S.–Canada border. In order to address these very specific and technical issues, McPherson suggested forming a commission to make recommendations for reducing barriers to trade. He suggested modeling it on the institutional arrangement of the International Joint Commission, a body that addresses border water issues with great technical expertise. This body makes recommendations on specific issues. However, each country can veto the commission’s decisions.

Transportation of goods, the automotive sector

Presenters: Thomas Klier, senior economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago; David Andrea, director, Forecasting Group, Center for Automotive Research; Kevin Smith, director of Customs Administration, General Motors; John Taylor, senior lecturer, Wayne State University; Harry Caldwell, chief, Intermodal Freight, Federal Highway Administration

Thomas Klier opened the session on the automotive sector by illustrating the concentration of auto sector plants in the Midwest. By mapping assembly plants, assembler-owned arts plants (so-called captive suppliers), as well as independent supplier plants for the U.S. and Canada, he showed that the auto industry is characterized by a very high degree of spatial concentration. The industry’s heart is southern Michigan and the area south of it, roughly defined by interstate highways 65 and 75, the so-called auto corridor. This auto corridor extends into Canada along Route 401 from Windsor to Toronto. The Detroit region continues to be the industry’s hub. Klier showed that essentially all of Canada’s auto industry is located within 400 miles of Detroit. Of the U.S. auto industry, two-thirds of independent supplier plants, 84% of assembler-owned supplier plants, and 58% of assembly plants are clustered within a day’s drive of the motor city (see figure 1).

1. Detroit as auto industry’s hub

| Plants within 100 miles |

Plants within 400 miles |

|||

| U.S. | Canada | U.S. | Canada | |

| Assembly plants | 33% | 25% | 58% | 100% |

| Captive plants |

49 | 55 | 84 | 91 |

| Tier 1 suppliers |

23 | 19 | 65 | 92 |

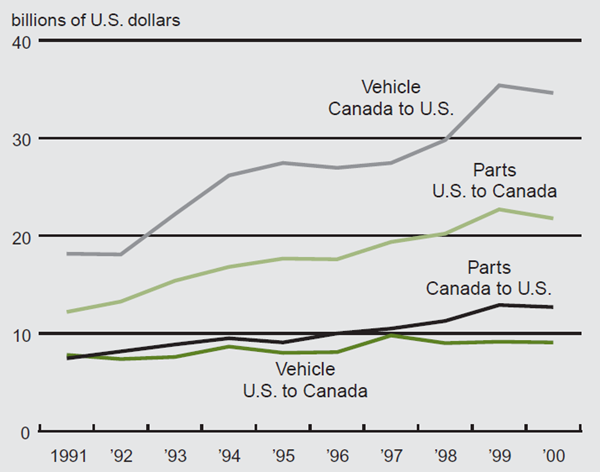

Next, David Andrea summarized a recent study on the role of the border for the auto industry. The study was commissioned by the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in July of last year. Its findings are based on a number of interviews with representatives from assembly plants, logistics suppliers, as well as tier 1 suppliers on both sides of the border. The study examined the cost that the U.S.–Canada border imposes on the North American auto industry. It takes into account the consequences of slowdowns at the border, inadequate infrastructure capacity, and staffing levels, as well as inefficient processes. Against the background of a highly integrated production system that involves many plants on both sides of the border (figure 2), shippers rely on just-in-time delivery, which schedules components to arrive at the factory as they are needed on the production line. While border delays were growing during 2000 and 2001 as the industry experienced record levels of production, the attacks of September 11 focused the industry on the need to be able to cross the border dependably within 20 minutes to 30 minutes. While border operations have essentially returned to normal since September 11, Andrea stated they remain fragile. Without a dependable way to ship components and vehicles between the U.S. and Canada, auto producers and suppliers in both countries face higher manufacturing and transportation costs, which in turn might affect sourcing and capital investment decisions.

2. U.S.–Canada automotive trade

Taking up this point, Kevin Smith noted that the auto industry is extremely cost competitive and cost sensitive. In a business environment where keeping costs down is crucial, border delays are unacceptable. Smith expressed concern that, post September 11, the fundamental issues of border operations have not yet been solved. Specifically, he mentioned the insufficient staffing levels at the border itself, necessary improvements to the border infrastructure, including more advanced equipment to screen shipments and people, and last but not least, the outdated systems technology underlying customs practices. The customs entry process now in effect is based on practices established in the 1950s and 1960s and systems put in place in the early 1980s. Smith explained that most U.S. Customs entries still require the presentation of paper invoices to obtain the release of goods. Today these invoices are created from electronic data maintained by importers and shippers purely so that they can be handed to customs officers and brokers, who then retype the information into other electronic systems. Smith argued that customs practices need to be aligned with business practices. The goal is to move to an approach where information is provided electronically to customs at the time the goods are shipped. General Motors has participated in such a prototype for the automotive sector (NCAP, or the National Customs Automation Program, which was established by the Customs Modernization Act of 1993), where data for low-risk traffic are automatically transferred to the border agencies. The goal is to have such a system implemented by 2006. Finally, Smith pointed out that security issues cannot be addressed at the border alone. By that token, a focus on border security should not complicate border transactions.

Next, John Taylor discussed the various elements that make up the border infrastructure. He explained that a border crossing consists of a variety of elements, such as ingress roads, intersections, toll booths, road capacity, inspection areas, and egress roads, all of which must function well for the process to work smoothly. Taylor pointed out that the greatest capacity constraints tend to be from inadequate staffing at inspection booths—at best, half the available booths tend to be staffed, leading to uncertainty and delays. Commenting on longer-term issues, Taylor reiterated the need to address institutional and regulatory constraints. He cited existing Cabotage laws as an example.

The final presenter on this panel, Harry Caldwell, discussed national freight policy. Caldwell illustrated that logistics expenditures, which comprise transportation costs, costs of owning and operating warehouses, ordering costs, and carrying costs of inventory, currently represent about 10% of the U.S.’s gross domestic product. While that share fell from 1981 to 1993, it has since stalled. One option to reduce this expenditure is to focus on building transportation infrastructure into seamless transportation corridors/gateways. While state governments currently have to fund improvements through their general department of transportation allotments, one could create a specific funding program for international freight gateways. Examples of emerging major freight access and security projects include the Seattle–Tacoma FAST (freight action strategy) corridor and the Detroit–Windsor border crossing. Caldwell argued that gateway policies need to achieve three objectives: increase freight throughput, increase national security, and reduce local congestion and community impacts. He used a border-crossing simulation to illustrate the potential benefits of improvements such as dedicated lanes for frequent users and the importance of channeling and sorting traffic into such lanes to avoid congestion and gridlock.

Keynote address

Speaker: The Honorable John Engler, Governor of Michigan

In his mid-morning keynote address, John Engler likened border crossings to the lifeblood of the Michigan and Ontario economies. To continue with the analogy, delays at the border are like blocking the artery. Engler said the border needs more agents to avoid backups. Backups could also be avoided if auto companies and others that make frequent crossings could have their trucks preapproved at their factories. On trade policy, he argued that it is very important to remove trade barriers on goods and workers. For example, Engler would like to see agreements so that professionals like nurses wouldn’t have to get two sets of credentials to work on either side of the border. He also proposed harmonizing regulations to make it easier for companies to bid on business across the border. In addition, he suggested that universities develop similar intellectual property agreements to make it easier to start new businesses. Engler endorsed the idea of a permanent binational commission to explore ways to ease problems such as border delays. He also announced a Michigan–Ontario summit on border issues to take place June 13–14, 2002, in Detroit.

Movement of people and capital

Speakers: Richard Egelton, senior vice president and deputy chief economist, Bank of Montreal; Michael Donahue, president and chief executive officer, Great Lakes Commission; Daniel Cherrin, director of public policy, Detroit Regional Chamber

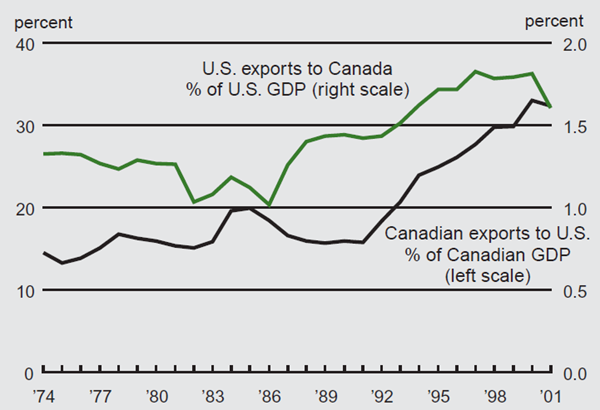

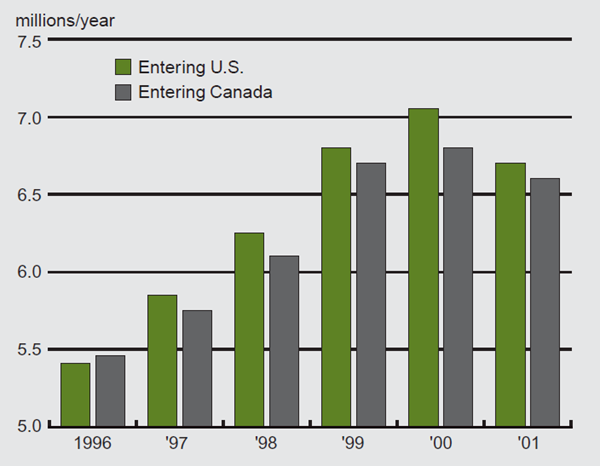

Richard Egelton illustrated the degree of integration of the U.S. and Canadian economies (figure 3). While the two economies are far from perfectly integrated,5 the growth in trade and related truck border crossings under the FTA has been remarkable. For example, from 1996 to 2000 alone, the number of trucks crossing the border annually increased from 5.5 million to just under 7 million annually (figure 4). Egelton also documented the increasing integration of both countries’ capital markets by referring to the increased flow of direct foreign investment between the two countries, as well as increased cross-border flows of bonds and equities. As for the movement of people, net migration flows are currently small with movements in both directions near historic lows. He suggested that the long-term decline in the migration rate is related to increasing labor force participation rates, resulting in more dual income households.

3. Growth in two-way trade

4. Cross-border truck volumes

Then, Michael Donahue discussed the quality of life, tourism, and the environment in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence system. He emphasized that the Great Lakes, the physical border separating the U.S. and Canada in the Midwest, represent a jointly shared resource. Regarding earlier suggestions on establishing a commission to explore further liberalization of trade between the U.S. and Canada, Donahue said it might be worthwhile to study the institutional arrangements that govern the Great Lakes.

Finally, Daniel Cherrin reiterated the sheer magnitude of the economic linkages between southeastern Michigan and southwestern Ontario. For example, 27% of Canada’s trade with the U.S. crosses the Ambassador Bridge in Detroit. With 41 U.S. and eight Canadian automotive assembly facilities located within a day’s drive of the Detroit region, it is estimated that U.S.$300 million in auto-related goods cross one of the region’s three border crossings daily. Cherrin specifically discussed the importance of the movement of people across the border for the Detroit metro area. Prior to September 11, about 110,000 Canadian workers would cross the border every day. Notably, the health care sector in greater Detroit depends heavily on a reliable flow of people across the border, with around 1,600 nurses, many of them highly skilled and specialized, commuting from the Windsor area to jobs in Detroit.

Conclusion

This conference highlighted the integration of the economy of the Great Lakes Region and a range of issues that need to be addressed, in view of the events of September 11, to prevent the U.S.–Canada border from becoming a stranglehold on regional commerce and trade. There seemed to be general agreement on the importance of pursuing a smart border approach. A number of speakers endorsed the concept of a zone of confidence; this would imply moving some security procedures away from the border through harmonization, as well as binational cooperation and communication. In addition, it was widely pointed out that a number of practices and regulations currently exist that impede the flow of goods and services across the border. Several participants recommended the establishment of a permanent commission, patterned, for example, after the International Joint Commission, to address these problems.

Notes

1 The Detroit area has two land-border crossings: the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit–Windsor Tunnel between Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario. Fiscal year 2001 traffic volumes over the bridge averaged approximately 10,800 passenger vehicles and 4,300 trucks each day; the tunnel averaged about 11,600 passenger vehicles and 240 trucks each day. Trade values between the U.S. and Canada total about U.S.$1.2 billion per day, 27% of which comprises merchandise crossing the Ambassador Bridge.

2 A more complete version of Sands’ remarks will appear as “The border after September 11: Learning the lessons of the Section 110 experience,” in A Fading Power: Canada Among Nations, Maureen Appel Molot and Norman Hillmer (eds.), Oxford University Press, 2002, forthcoming.

3 The Customs Modernization Act of 1993 grew out of concerns of many in Congress that the policing of U.S. borders required improvement in order to cope with the growing pressures of trade and individuals crossing into and out of the U.S. with increasing frequency. Its passage was an important precursor to the congressional ratification of NAFTA and related legislation in November of that year.

4 See Government of Canada, 2002, “Joint statement by the deputy prime minister of Canada, John Manley, and the director of the White House Office of Homeland Security, Tom Ridge, on progress made in the Smart Border Action Plan,” press release, Buffalo, NY, May 16.

5 Egelton cited John McCallum’s 1995 paper, which showed interprovincial trade in Canada is 19 times as intense as trade with neighboring states. See John McCallum, 1995, “National borders matter: Canada–U.S. regional trade patterns,” American Economic Review, June, pp. 615–623.