This article documents the prevalence of blockbusting—the orchestration of racial turnover in urban neighborhoods—throughout many major U.S. cities from the 1950s through the 1970s.

In this Chicago Fed Letter, we highlight a few facts about blockbusting in post-World War II America:

- Across the U.S., we find evidence of blockbusting in 45 of the 60 largest cities.

- Within U.S. cities, we often find a large geographic footprint—e.g., in Chicago, we find blockbusting occurred in 15% of census tracts that were not majority Black in 1950.

- Within one neighborhood in Baltimore, we estimate that blockbusters bought two-thirds of all properties and that 96% of the neighborhood’s population in 1950 had relocated by 1970.

Overall, blockbusting appears to have been a very common practice across American cities, with the potential to have significant impacts on the lives of past and future residents of the neighborhoods where it occurred.

What was blockbusting?

Blockbusting was a pernicious practice in the history of housing and financial discrimination. Commonly associated with neighborhood “tipping” and White flight, blockbusting is an attempt to stir up race-based panic and orchestrate the large-scale turnover of a neighborhood’s housing stock in order to profit from the turnover. Scholars have described the tactics used by blockbusters to create race-based panic among existing White homeowners as preying on their racial prejudices and financial worries, thereby encouraging homeowners to sell their houses below market value.1 After acquiring the properties, blockbusters would then exploit the limited housing and financing options available to incoming Black residents in order to sell and finance those same homes at large markups and often with onerous lending terms. While the practice was eventually outlawed in 1968,2 blockbusting had long-lasting impacts, including high rates of involuntary dispossession, for these incoming residents, many of whom were first-time homeowners.

The historical context: Tight housing markets for Black Americans

The advent of blockbusting in the postwar period was precipitated by a couple of larger trends in U.S. housing markets. First, housing supply growth was severely limited during World War II, as national resources were diverted toward supporting the wartime effort. Construction fell by about 75% from 1941 to 1944, as measured by new nonfarm housing units.3 Combined with the fading of the 1930s Great Depression and increasing housing demands from veterans returning to civilian life postwar, the housing market coming out of World War II was significantly tighter than it was going in.

Second, housing demand in the U.S. North was abnormally high due to an influx of new Black migrants during the Second Great Migration. Over the course of the 1940s, almost 1.5 million Black people migrated from the South to the North. Compared with the prewar migration level of about 475,000 migrants in the 1930s, this marked a large increase in the number of Black people moving into already stretched housing markets.4 This migration trend would continue through the 1970s, with over 4 million Black people relocating from the South into cities in the North. This influx resulted in a very high demand for housing among Black families in northern cities by the end of World War II and during the postwar period. However, segregation meant that incoming Black buyers had limited housing choices, with many urban neighborhoods in the North unavailable to incoming Black migrants.5 This barrier was relaxed by the 1948 U.S. Supreme Court decision that deemed unconstitutional restrictive covenants in real estate deeds that prohibited the sale of property by race.6 While the ruling formally allowed Black homebuyers to purchase houses in previously segregated White neighborhoods, it also created an opening for unscrupulous real estate brokers to take advantage of the fear generated by the potentially changing neighborhoods.

Similar neighborhood demographic shifts had occurred in the decades prior to the rise of blockbusting, with neighborhoods that had previously been majority White shifting toward being majority Black.7 However, based on our research, we believe this phenomenon was not previously as widespread across cities in the U.S. Blockbusting in the postwar period appears to have represented a more widespread practice and was associated with the well-studied phenomena of neighborhood “tipping” and White flight.

Blockbusting prevalence

We have identified reports of blockbusting in 45 of the 60 largest cities in the U.S. during the 1950s and 1960s. This evidence comes from a careful review of a wide-ranging set of sources—scholarly histories, accounts in the news media, official reviews, and other materials—which made explicit reference to blockbusting activities within a neighborhood, either by name or through the description of blockbusting tactics. It is difficult to verify these reports of blockbusting, but given that the practice was legal, we take most plausible accounts at face value, with the only exceptions being instances of conflicting accounts, which garnered closer examination. Reference to racial turnover within a neighborhood alone is not a sufficient indicator of blockbusting activity.8 Ultimately, we have identified 950 specific census tracts across 39 cities that were the sites of purported blockbusting.9 These tracts represent about 8% of all the census tracts that were not already majority Black by 1950 in these cities. Given the somewhat limited availability of historical records on the subject, this figure could represent an underestimate of the true extent of blockbusting in major U.S. cities during this time period.

As examples, we examine two cities—Chicago and Baltimore—and describe the extent and impact of blockbusting in each. By evaluating the where and how of blockbusting, we can then begin to understand the longer-term impacts of these episodes.

Chicago

In Chicago, we identified blockbusting events from the 1950s and 1960s in 144 of the 805 census tracts that were not majority Black in 1950. This represents a significant share of the city: In 1950, 15% of the city’s population that did not already live in a majority Black neighborhood lived in a tract that would experience blockbusting. These instances of blockbusting were largely concentrated in neighborhoods on the West and South Sides of Chicago. This pattern largely matches the common narrative of Chicago’s blockbusting history, as Lawndale on the West Side and Englewood on the South Side are two particularly infamous blockbusting sites.

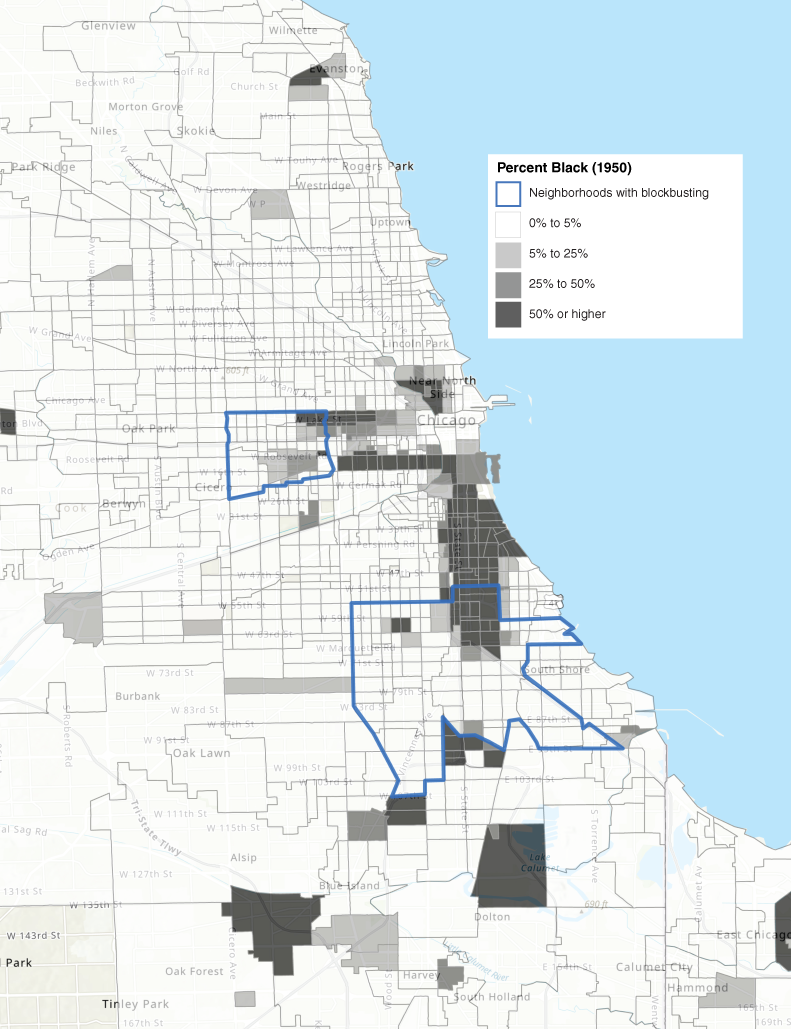

Figure 1 suggests a geographic pattern in which blockbusting occurred in neighborhoods near existing majority Black neighborhoods, but somewhat idiosyncratically. Additionally, the geographic prevalence of blockbusting illustrates just how pervasive an issue it was.

1. Map of blockbusting in Chicago neighborhoods and the 1950 Black population share in U.S. census tracts

Sources: Authors’ analysis based on data from the University of Minnesota, IPUMS NHGIS; and ArcGIS Online.

Baltimore

We now turn to a more fine-grained analysis of blockbusting in a single neighborhood to illustrate the sweeping scale of blockbusting on a local level. In Baltimore, the neighborhood of Edmondson Village, depicted in figure 2, is the site of one of the most notorious instances of blockbusting in American history.10 Using property-level data, we analyze all of the housing transactions on 2,600 properties in this neighborhood from January 1954 through December 1975. Figure 2 highlights in red any sales to realty companies—likely blockbusters—during that time period. We find that realty companies purchased about two-thirds of all properties, mostly over the period 1955–65. Most of the remaining properties also changed hands, but without involving blockbusters. As a result, comparing the 1950 U.S. Census with the 1970 U.S. Census reveals a stunning amount of population turnover among the original 20,000 residents of this neighborhood, with the Black population share of this neighborhood up from almost 0% to 96%.

2. Blockbusting in Edmondson Village, Baltimore, 1954–75

Note: Properties highlighted in red indicate any sales to realty companies—likely blockbusters—in each time

period, and properties highlighted in pink indicate such sales that occurred in previous periods.

Sources: Authors’ analysis based on data from the Maryland State Archives, available online, and other archival materials; and ArcGIS Online.

Based on the prices of property transactions in this data set, we calculate that when reselling these properties to incoming Black homebuyers, blockbusters charged an average markup of around 45% on home prices—a markup labeled by community groups at the time as the “Black tax.” This markup also reflected the relatively low prices at which the blockbusters purchased the residential properties, possibly due to panic by existing residents. While some research, such as Ed Orser’s (1997) social and cultural study of blockbusting in Baltimore, has suggested that the first White families to sell their homes were often given a high price in order to induce a sale, we cannot find systematic evidence of this practice in Edmondson Village. That said, certainly some instances along these lines likely did occur.

Blockbusters maintained a tight grip on prices through the mid-1960s, at which point there remained very few unsold properties in Edmondson Village. At the same time, we find that prices on transactions not associated with blockbusters fell roughly between the prices bought and sold by blockbusters, suggesting that both the buyers and sellers could have been better off by dealing directly with each other, without a blockbusting intermediary. However, as Orser (1997) suggests, a combination of racial prejudice and panic often led existing White homeowners to deal with blockbusters instead of directly with Black families.

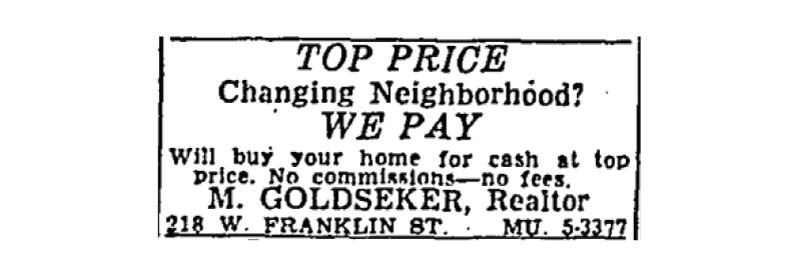

To complete these home transactions, blockbusters in Baltimore would often engage in aggressive and sometimes fraudulent practices, many of which became illegal after the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. As an example of an aggressive practice, blockbusters were known to blanket neighborhoods with advertising suggesting that the neighborhood was undergoing a racial transition. Figure 3 shows an example of an advertisement that would likely be illegal today, given the question “Changing Neighborhood?” Another set of aggressive practices involved installment contracts, which blockbusters often used to finance the sale of homes, especially for homeowners who could not otherwise obtain mortgage credit. Unlike mortgages, installment contracts allowed a blockbuster to legally retain ownership of the home until a series of payments had been completed by the buyer. Until they paid off their debt, these homebuyers essentially functioned as renters, leaving them vulnerable to the loss of their equity without the protections of mortgage law. As for fraud, two blockbusters were given prison sentences after being convicted of defrauding the Veterans Administration by arranging for false attestations on credit applications by buyers.11

3. 1958 advertisement in Baltimore’s The Sun newspaper

One result of the financial structure created by blockbusters was a high rate of foreclosure for the new homeowners. Overall, based on the data set of Edmondson Village property transactions, we calculate about a 13% rate of foreclosure from the end of 1966 through the end of 1976—both on mortgages taken out by the new homeowners and on installment plan loans. Foreclosure rates were particularly elevated on loans made in coordination with the Veterans Administration or Federal Housing Administration, reaching about 25%. In comparison, we calculate a foreclosure rate on transactions between individuals without the use of an intermediate real estate company to be 2.5%. These foreclosures put downward pressure on prices and the foreclosures themselves represented a significant loss of wealth through accumulated equity.

Conclusion

We have documented the widespread activity by blockbusters in the postwar U.S.—across cities, within cities, and within a neighborhood. In a separate working paper,12 we analyze the impact of these practices on the wealth that Black homeowners were able to accumulate when they became homeowners after moving into specific neighborhoods for the first time. In the paper we find that across census tracts, blockbusting resulted in relatively lower housing prices by 1980 or 1990. For instance, using data from Edmondson Village in Baltimore, we find evidence consistent with downward pressure on home prices stemming from affordability problems; our research suggests that these historical affordability issues can be traced back to the high prices charged by blockbusters and resulting high rates of foreclosure, as well as to the underwriting fraud that at least some blockbusters engaged in when arranging for mortgage credit. These blockbusting practices were widespread and ultimately harmed Black homeowners’ ability to build wealth through homeownership.

Notes

1 W. Edward Orser, 1997, Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

2 Discrimination in the sale or rental of housing and other prohibited practices, 42 U.S.C. § 3604 (1968), available online.

3 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1948, Construction in the War Years 1942–45: Employment, Expenditures, and Building Volume, Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, No. 915, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, available online.

4 James N. Gregory, 2009, “The Second Great Migration: A historical overview,” in African American Urban History: The Dynamics of Race, Class and Gender since World War II, Kenneth L. Kusmer and Joe W. Trotter (eds.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 21.

5 For examples, see Beryl Satter, 2010, Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America, New York: Metropolitan Books; Todd M. Michney, 2017, “Beyond ‘White flight,’” Belt Magazine, May 31, available online; Kevin Fox Gotham, 2002, “Beyond invasion and succession: School segregation, real estate blockbusting, and the political economy of neighborhood racial transition,” City & Community, Vol. 1, No. 1, March 1, pp. 83–111, Crossref; and Thomas J. Sugrue, 2005, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

6 Aradhya Sood, William Speagle, and Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, 2019, “Long shadow of racial discrimination: Evidence from housing covenants of Minneapolis,” University of Minnesota, working paper, September 30. Crossref

7 Prottoy A. Akbar, Sijie Li, Allison Shertzer, and Randall P. Walsh, 2019, “Racial segregation in housing markets and the erosion of Black wealth,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper, No. 25805, May. Crossref

8 Though we use this outlined process to identify probable blockbusting locations for research purposes, this process may not meet evidentiary standards required in formal legal proceedings.

9 Though we find reports of blockbusting in 45 cities, we focus on 39 cities where we were able to identify specific neighborhoods in which blockbusting reportedly occurred.

10 Orser (1997).

11 A. S. Abell Company, 1961, “Realty firm officials get terms, fines: 2 are sentenced to 2 months, assessed $15,000 each,” Sun, April 15, pp. 32, 21.

12 Daniel Hartley and Jonathan Rose, 2023, “Blockbusting and the challenges faced by Black families in building wealth through housing in the postwar United States,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, working paper, No. 2023-02, January. Crossref