Introduction

The community development field faces new and unprecedented challenges stemming from the pandemic and stay-at-home policies. Indeed, the pandemic laid bare longstanding issues around structural racism, economic inequality, and limited social mobility in our most vulnerable communities. The fundamentals of community-building offer insights, and past redevelopment interventions that harmonized diverse actors and resources can inform current efforts to bring about a more inclusive recovery. As an example, the New Communities Program (NCP) provided a framework for the redevelopment of many Chicago neighborhoods over a decade between 2001 and 2011. This article explores the lessons learned from the NCP, as well as the durable gains—tangible and intangible—experienced by NCP communities.

The NCP evolved from an earlier generation of community development practice that focused almost exclusively on the development of affordable housing (see box 1). Recognizing the limitations of that narrow approach, neighborhood leaders in Chicago under the guidance of the LISC/Chicago office established a more robust and comprehensive way of thinking about neighborhood development. Those conversations led to the creation of the NCP. With a ten-year funding commitment from the MacArthur Foundation, the program was established in 20 Chicago neighborhoods, becoming the largest and longest comprehensive community initiative (CCI) in the nation.1

Some lessons learned

LISC/Chicago served as the central intermediary for the NCP, but it relied on local lead agencies (community development organizations of various types) to provide leadership, planning, staffing, and project implementation. A key feature of the NCP was the creation of a Quality-of-Life Plan (QLP) that offered both an organizing tool and a practical guide to the community’s self-directed development.

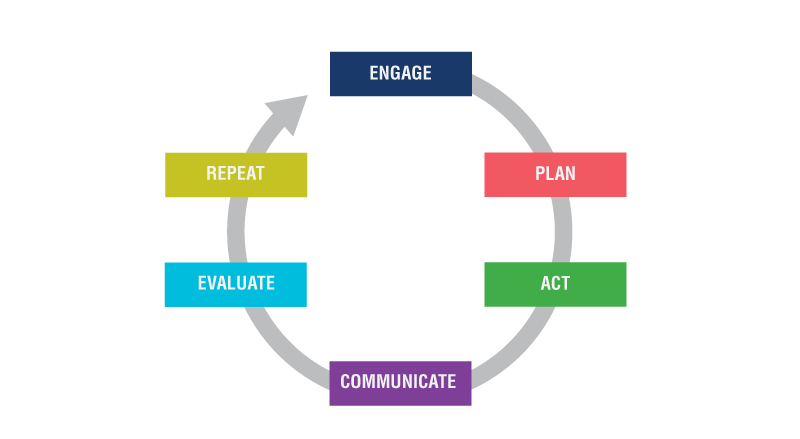

As lead agencies engaged their communities, identified collaborators, and put their QLPs together, a recurring “virtuous cycle” became evident. Organized stakeholders came to consensus around a common vision and specific projects. Working together on small-scale “early-action” projects, they deepened relationships, trust, and the confidence that comes with achieving goals. Continuous communication of successes, challenges, and ongoing activities attracted participation, partners, and investors. Public recognition of successes, coupled with honest self-evaluation, course corrections, and adjustments gave participants the courage to confront larger challenges and more imposing projects.

As NCP communities completed plans, accomplished early-action projects, celebrated their successes, and embraced more complex challenges, the process became a mantra: Engage, Plan, Act, Communicate, Evaluate, Repeat.

As this QLP-informed process was repeated across multiple Chicago communities, seven key lessons emerged.

- A long-term funding partner is critical.

The importance of the MacArthur Foundation’s long-term commitment to NCP cannot be overstated and was critical to the program’s sustained efforts in communities. Their generous funding established the program, but their decision to support NCP over a decade made it clear to all participants that they fundamentally understood the complex nature of community change, as demonstrated by the scope of their investment. The long commitment timeline also gave communities the time to implement their plans, establish credibility, and grow their capacity so they were better able to sustain their work once the NCP funding support sunset. This also sent an important message to other funders regarding the impact potential for their investments.

- Investing in relationship-building early pays dividends.

An inclusive, participatory process that welcomes everyone may take time to develop, but it pays dividends when negotiating a common vision, goals, and the implementation of plans. Communities that began with a systematic process of relationship-building and maintained that collaborative process through the planning period into implementation progressed more quickly and effectively.

- Building a social compact helps drive energy and momentum toward common goals.

All communities consist of diverse constituencies with multiple and often conflicting interests. Successful comprehensive community initiatives emerge when lead agencies and their partners—including local government officials—commit to an agreed upon vision and a set of projects that unites stakeholders, clearly defines their responsibilities, keeps them engaged, and moves them in the same direction. Forging a social compact—a “consensus-building covenant” within the community—is a critical step in implementing community change. The inclusion of local government officials in the process helps build wider support within the community and private sector. It also gives local stakeholders the “hustle and muscle” to manage projects to completion, and the accountability to ensure that those projects are in the community’s interest.

- Build diverse relationships that will withstand the challenges of community development.

Creating and nurturing new (or enhanced) relationships in a neighborhood, sometimes among leaders and organizations that have contentious histories, requires honed community-building skills. Often, it’s a matter of finding the right “sweet spot” that will persuade others to join the table. Always it’s a matter of developing the personal and institutional relationships that will endure through both successes and failures. During NCP, this was a particular responsibility for the CEOs and board chairs of the lead agencies.2

- Dedicated skills for project management help ensure project execution.

Project management skills are essential in implementing Quality-of-Life plans. Lead agencies that were the most effective at executing their projects were those that either had dedicated project management staff, or had staff with other core responsibilities but also skill and experience in project management.

- Investing in professional communications offers important feedback to stakeholders and elevates community efforts to a wider audience.

From the outset of the NCP, LISC/Chicago invested heavily in documentation and communications, using professional journalists, photographers, and designers to support the community planning processes and provide stories for websites and newsletters. Real-time, fact-focused documentation of meetings and programs offered important feedback to stakeholders and LISC program officers. Vivid photography and striking design for publications attracted attention and documented progress. Websites, slideshows, and newsletters showcased results and helped spread the word about the NCP. Stories, case studies, and reports served as an important means to measure and evaluate outcomes. The professional caliber of these products elevated the profile of NCP efforts both within the communities themselves and to a national audience.

- “Activist” program officers help communities achieve more.

Communities achieve more when they are supported by activist program officers at the central intermediaries, in this case, LISC/Chicago. Activist program officers understand organizing and engagement, partnerships and collaboration, and deal-making, not just in real estate, but also in education, arts, economic development, parks, sports activities, and more. They act as a part of the neighborhood team, as an ally and supporter of neighborhood efforts, always seeking new, different, and better ways to accomplish the visions set out in the QLPs. The program officer links organizations with technical assistance, and potential partners and resources. When problems arise, the LISC program officer works with lead agencies to offer guidance, solve problems, and help them help themselves. The program officer also provides oversight and helps maintain focus on the community’s vision and goals by reinforcing the expectations that the NCP participants place on themselves through the QLP planning process.

Tangible outcomes

The NCP leveraged nearly a billion dollars into the participating communities over its ten years. Over 800 discrete projects ranged from the creation of a neighborhood newspaper to major real estate developments. Among those projects were several innovative city-wide programs in a wide variety of fields, including health care, education, economic development, real estate development, broadband access, and youth programming (for some examples, see text box on the Quad Communities Development Corporation). These programs were complex to develop, involving funding from multiple grantors, for example.

By the end of the program in 2011, there were 13 “Centers for Working Families” (now called Financial Opportunity Centers), five “Elev8” in-school neighborhood health clinics, seven “Smart Communities/Family Net Centers” providing internet access to entire regions, multiple youth recreational and arts programs (such as the well-known summertime program “Hoops in the Hood”3), multiple retail/commercial developments and over 5,000 new housing units. Nearly all these programs are still in place.4

In fact, many of the original NCP participants, plus a few other neighborhoods in Chicago, still utilize the Quality-of-Life planning process to keep their communities organized and to encourage investment in their neighborhoods (see text box about Auburn Gresham).

Intangible outcomes

With nearly a billion dollars leveraged on behalf of 20 Chicago communities through the NCP program, the scale of the initiative is clear. However, there were important intangible outcomes that are proving to be enduring.

Creation of a neighborhood platform—We believe that NCP’s most remarkable outcome, in addition to the intrinsic value of the program investments and dozens of completed projects, was the evolution of a neighborhood platform. As communities engaged in planning, early-action projects, and the implementation of initiatives from their QLPs, they developed a web of both internal and external relationships—a virtual infrastructure—that served as a base for accomplishing the many projects and activities conceived in their plans. Ultimately, we believe this platform helped connect the collective efforts of many stakeholders in their communities into the social, political, and economic dynamics of the larger region.

Leading to a delivery system—This web of relationships and the neighborhood platform united often disparate organizations and individuals in common purpose, creating a program delivery system, manifesting in the ability to get things done. Over time, relationships evolved and grew, accomplishments accumulated, and an infrastructure emerged to deliver a vehicle for investment for funding from the public, private, and philanthropic sectors. The neighborhood platform also became an information delivery system, through which technical resources, innovation, and communication flowed across the organizations and individuals working toward a common purpose.

Perhaps most importantly, we believe the neighborhood platform made the NCP neighborhoods resilient in the face of economic challenges that inevitably arose. For example, during the Great Recession of 2008 (see text box) many NCP communities faced extreme levels of home foreclosures and their lasting impacts on both housing stability and household credit histories. At the same time, the platforms and systems in place enabled those communities to leverage the federal and state resources designed to mitigate these challenges at the local level.

Focus on the practice of community development—the NCP stands out from other CCI models owing to its focus on the systems of relationships—personal and institutional, social and economic—that underlie neighborhoods. When these systems can be coalesced through community action into a platform for neighborhood development, we believe they can support local leadership and decision-making. These systems also help inform channels for community action and galvanize external investments and internal commitments. The platform also connects to the larger systems in which communities are embedded, including the city and region, in a dynamic process of mutual influence.

From this perspective, the practice of community development takes on a new meaning: It is the art and process of bringing together experience, knowledge, skill, and diverse agents for the purpose of influencing the long-term trajectory of neighborhood systems. Importantly, the diverse agents active in those systems have agency and play a key role in influencing the trajectory. The trick to success for community organizers is to comprehend the many elements and actors at play in a neighborhood as they align toward a common good. The NCP moved the practice of community development from a standard “theory of neighborhood change” to a much more robust “theory of influence.” As a result, we believe the NCP empowered communities to set their own priorities, take responsibility for their own actions, and chart a course for an improved future.

Implications for now

As new leaders and practitioners emerge, the experiences of the NCP can provide some reassuring guidance embedded within the fundamentals of community development.

In spirit and in practice, many of the lessons learned through the NCP still guide community development efforts today, even as we strive to respond to today’s challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic and widening inequality, among others.

For example, the Southwest Organizing Project (SWOP), an NCP lead agency in the Chicago Lawn community, applied its NCP experience in creating, developing, and administering a local school health clinic to organize the Southwest System of Care Network. This coalition of mental health, healthcare, social service providers, schools, after-school providers, and youth leadership development programs coordinate care for young people and their families. As the Covid-19 pandemic began, SWOP and its network pivoted to combat the incidence of Covid-19 in their neighborhood, hiring 18 residents as contact tracers and mobilizing teams of healthcare professionals to vaccinate residents.

In Humboldt Park, Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation organized multiple agencies through their NCP leadership team to implement a robust mask and vaccination program in each of their residential properties. As in other communities, having coalitions (the platform) in place prior to the pandemic helped ensure that a response to the pandemic could be quickly mobilized. With the legacy of the NCP still active in their communities, Chicago Lawn and Humboldt Park were able to not only react to the emergency phase of the pandemic, but also respond to community needs as the crisis evolved.

In another example, many NCP participants, like the Greater Auburn Gresham Development Corporation (GADC), continue to use the Quality-of-Life planning process as a way to organize their communities and provide a vision for their future.5 Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development continues to use the QLPs as a guide for the city’s investments in neighborhood projects, such as through its Invest SouthWest initiative. Organizations in other cities, such as Houston and Indianapolis, also use the NCP approach to guide much of their work.6

Whether responding to an unprecedented crisis or striving to reverse decades of disinvestment, the NCP QLP process of building a platform to support resource delivery (and deployment) by focusing community development efforts on common goals can lead to important tangible and intangible outcomes. When these lessons and practices are observed at scale and over time, they provide important insights into how organizing contributes to community resiliency and revitalization.

Notes

1 The design for the NCP’s methodology was largely informed by the ground-breaking Comprehensive Community Revitalization Program (CCRP) in New York City. See Miller and Burns, 2006.

2 See Bill Traynor’s excellent article distinguishing between community-organizing and community-building, in The Community Development Reader, Fillippis and Saegert, 2008.

3 For a video of “LISC Chicago’s Hoops in the Hood turns troubled streets into safe places to play” see https://vimeo.com/32428151.

4 From the MacArthur Foundation-commissioned “An Evaluation of

the New Communities Program” by MDRC,

https://www.macfound.org/press/evaluation/assessment-new-communities-program.

5 “LISC’s Quality-of-Life Planning Bettering Neighborhoods throughout Chicago,” highlights several of the 23 QoL plans completed in Chicago neighborhoods since the conclusion of the NCP.

6 LISC/Houston’s 12-year old GO Neighborhoods program supports Quality-of-Life planning and comprehensive community development in 13 neighborhoods; and LISC/Indianapolis invests in seven Quality of Life Neighborhoods (based in part on the NCP model) that have created plans and are working to achieve their visions.

Box 1: LISC/Chicago’s New Communities Program (NCP)

In 1995, Chicago’s community development field was in crisis. Several high-profile community development corporations (CDCs) in Chicago and nationally had failed under the burden of their real estate portfolios. Government, philanthropic, and neighborhood leaders grew frustrated as new housing was developed, yet many neighborhoods still declined.

In response, LISC/Chicago organized a public 18-month dialogue among the “Futures Committee,” comprised of community development, political, and civic leaders, and called on them to recommend a path forward. The committee produced a document entitled Changing the Way We Do Things, which aimed to refocus the community development world toward a more nuanced, comprehensive approach.

The New Communities Program (NCP) grew out of a small demonstration effort in 1999 (“the New Communities Initiative”) in three neighborhoods. In 2001, with the support of the MacArthur Foundation, the demonstration expanded to become the NCP in 20 communities (with 16 “lead agencies”) in a ten-year endeavor and became the nation’s largest comprehensive community development program.

LISC/Chicago empowered a lead agency in each neighborhood as an intermediary to organize the community, coordinate planning, develop partnerships, manage projects, and communicate successes. Agencies engaged stakeholders, adopted a common vision, crafted “quality-of-life” (QLP) plans, and identified issues, strategies, and projects to realize their vision.

Planning teams targeted “early-action projects”—“doing while planning”—to create short-term visible improvements to showcase positive activities and grow collaborative relationships, while implementing larger, catalytic projects designed to inspire hope, promote investment, and transform neighborhoods.

With the help of professional journalists, an ongoing communications process spread the word about successes and challenges and attracted partners and resources. LISC served as the central intermediary, channeling resources and expertise to communities and coordinating resources among its lead agencies to develop and maintain staff and program continuity to implement multi-layered, complex projects.

Box 2: Quad Communities Development Corporation

Concurrent with the creation of the NCP, the Quad Communities Development Corporation (QCDC) was formed to improve the quality of life of four Chicago lakefront communities. Its QLP focused upon driving economic development, improving neighborhood schools, and preparing the local work force for quality employment and financial stability.

With support from the City of Chicago and LISC/Chicago, the QCDC formed a Special Service Area taxing district, a Tax Increment Financing District, and a Small Business Improvement Fund to revive the Cottage Grove Avenue retail corridor. They also partnered with Cara Chicago to establish a Financial Opportunity Center to provide residents with career counseling and financial coaching; and implemented LISC/Chicago’s “Elev8” program to transform the educational achievement and life outcomes at a local middle school.

QCDC leaders knew that restoration of the Cottage Grove corridor (the former economic center of Chicago’s historic Bronzeville community) would require a major new development to catalyze investment throughout the neighborhood. For nine years, they planned, organized, and advocated for a mixed-use project at the community’s busiest intersection. The result: the “Shops & Lofts at 47,” a $46 million retail and residential project with 96 mixed-income housing units, 55,000 square feet of retail space, and anchored by a Walmart Neighborhood Market. Envisioned by the community, supported by LISC Chicago, the City of Chicago, and dozens of partners, Shops & Lofts brought more than 100 new jobs to the community—and with them, hope, optimism, and new investment.

Box 3: Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation

As the lead agency in Chicago’s Auburn-Gresham community, the Greater Auburn Gresham Development Corporation (GADC) has spearheaded community improvement strategies since 2001. GADC staff and leaders have implemented initiatives focusing on economic development, education, housing, financial stability, health impacts, public safety, transportation, and more. Since its founding, Executive Director Carlos Nelson has steered the agency’s growth from one person to more than 17 staff members. Also, neighborhood leaders, public officials, and funders view GADC as a catalyst for positive change in the community.

In our view, the GADC’s comprehensive approach, dynamic network of partners, and strong and dedicated leadership contribute to its success. It was selected from over 80 applicants as the inaugural winner of the $10 million Chicago Prize, a 2020 competition sponsored by the Pritzker Traubert Foundation to promote community investment in Chicago’s South or West Sides. The neighborhood’s most recent Quality-of-Life Plan highlighted important investment-ready projects to be funded by the Chicago Prize.

Among those projects is a partnership with the Urban Growers Collective and Green Era Partners to develop a $50 million campus with a Healthy Lifestyle Hub, a digital community center, an Urban Farm campus, and an anaerobic digestor. The campus will also feature the transformation of two vacant city blocks into vibrant community spaces, providing equitable access to a new health care clinic for area residents. This project will involve over 300 construction jobs and is expected to house 300 permanent professional jobs once completed.

Box 4: The Great Recession and the Southwest Side of Chicago

The Great Recession of 2008, the foreclosure crisis, and its aftermath were devastating to Chicago’s Southwest Side communities. As the economy declined, and job losses mounted, the Chicago Lawn neighborhood was hit with 11,000 foreclosures, resulting in 700 vacant properties.

The Southwest Organizing Project (SWOP), the area’s NCP lead agency, mounted an extraordinary campaign—Reclaiming Southwest Chicago—to mobilize partners and secure resources in a comprehensive effort to confront the economic and social challenges, strengthen the community, and create affordable homes, safe streets, and good schools.

SWOP assisted over 625 families in keeping their homes through aggressive anti-foreclosure organizing. Working with the City of Chicago and its Micro Market Recovery Program (MMRP), they secured $900,000 from the City and $3 million from the Illinois Attorney General to target a 20-block area with housing subsidies, flexible loans, and grants for renovation. Local and citywide organizations joined the effort.

More than 100 affordable homes and apartments were acquired and renovated. Vacancies in the target area decreased from 93 properties to eight. Seventeen more properties are being renovated. Through an organizing campaign with United Power for Action and Justice, SWOP obtained commitments for $10 million of public funding to reclaim properties throughout the community.

Biographies

Joel Bookman led a community development corporation in Chicago for 25 years, was director of programs for LISC/Chicago from 2005 to 2013, and currently serves as a community development consultant and president of Bookman Associates, Inc. Andrew Mooney was the Commissioner of the Department of Planning and Development for the City of Chicago from 2010 to 2015 and served as executive director of LISC/Chicago from 1996 to 2010. Mooney and Bookman also co-founded LISC’s Institute for Comprehensive Community Development.