What is a water service line?

Every day in the United States, an estimated 6 million to 12 million lead service lines (LSLs) that supply drinking water to homes potentially expose people to lead.1 Regular exposure to even small amounts of lead endangers health and, for children, presents a risk of developmental delays and long-term behavior and learning problems.2 The only way to eliminate lead exposure from LSLs is to replace the LSLs with new pipes.3 However, LSL replacement has generally been slow and sporadic, rarely occurring unless a pipe breaks or the law requires more widespread replacement due to a lead-contamination crisis.4

New federal funding and recent changes to federal and state laws may encourage or require water systems to stop waiting for crises and make plans for rapid replacement. Yet more widespread and rapid LSL replacement will present new challenges—many of them economic and financial. Addressing these challenges is critical for the Upper Midwest, where LSLs are particularly prevalent, and for low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, which face higher concentrations of LSLs.5

With policy developments bringing increased public attention and new resources to the problem of lead in drinking water, staff at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago are working to advance understanding of the economic and financial challenges and potential solutions, as part of the Federal Reserve’s mission to foster economic opportunity, advance a strong and inclusive economy, and promote an efficient financial system. We are leveraging our expertise in public policy, finance, and community economic development and aim to partner with those already deeply involved in this issue. We are conducting research, listening to the public’s concerns, and consulting with national, regional, and local stakeholders. Our goal is to help identify opportunities to overcome economic and financial barriers to widespread and rapid replacement of LSLs and help unlock the benefits of cleaner water for the health and growth of our communities.

New laws and new funding may help accelerate LSL replacement, particularly in Midwest and Great Lakes regions

The five states of the Chicago Fed’s region (Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin) are estimated to have 2 million to 2.9 million LSLs, representing as much as one-third of all LSLs in the United States (see map).6 The city of Chicago alone has an estimated 400,000 LSLs, the most of any U.S. city.7

Large-scale and rapid LSL replacements in the region typically occur when water testing reveals very high lead levels, water treatment does not reduce lead below the necessary threshold, and federal or state law demands further action. Madison, WI, completed a decade-long effort in 2011 to replace more than 8,000 LSLs,8 and Flint, MI, replaced more than 10,000 LSLs over five years starting in 2016.9 Residents of Benton Harbor, MI, have been struggling for safer drinking water since water testing revealed high lead levels in 2018.10 In November 2021, Michigan’s governor announced a goal to remove all of Benton Harbor’s LSLs by March 2023.11

Federal authorities took four steps in 2021 to accelerate the replacement of LSLs.

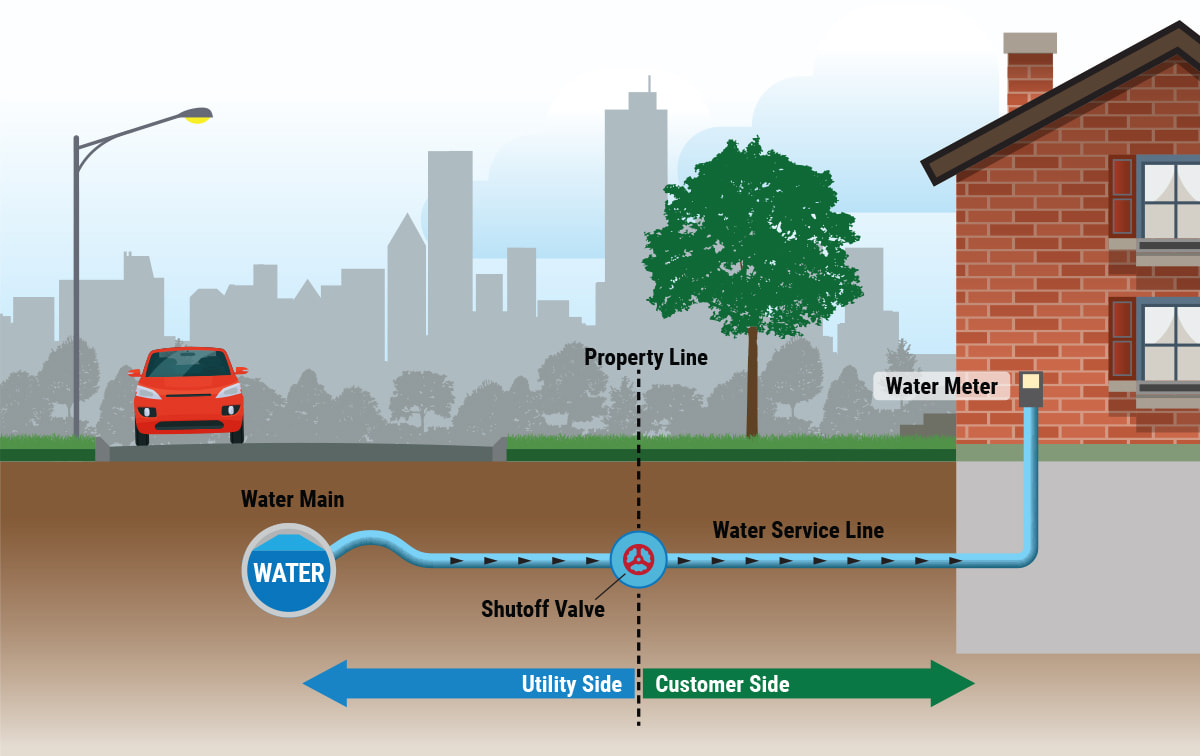

- The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a 2024 deadline for all water systems in the U.S. to inventory LSLs and develop a plan to replace them. Because typically some parts of LSLs are owned by utilities and other parts by customers (see Infographic), these plans must include strategies to communicate with customers and to support those who cannot afford to replace the portion of the LSL that they own.12

- Congress modified an EPA grant program to let water systems help families pay for their share of LSL replacement.13

- The EPA updated required water testing methods. The agency expects the updated methods to more frequently detect high lead levels and increase the number of water systems required to replace LSLs on an expedited timeline.14

- Congress appropriated $15 billion to help states pay for or subsidize LSL replacement over the next five years.15

The EPA also announced in December 2021 that it plans to issue new regulations by 2024 that will further accelerate replacement of all LSLs, which it called “an urgently needed action to protect all Americans from the most significant source of lead in drinking water.”16

In recent years, states in the Chicago Fed’s region have also changed laws to promote acceleration of LSL replacement. For example, Michigan revised its environmental regulations in 2018 to require all water systems to replace all LSLs before 2041.17 In 2021, Illinois lawmakers also set LSL replacement deadlines.18 Illinois’s new deadlines give more time to water systems with more LSLs. The smallest water systems must replace all LSLs within 20 years, while Chicago has until 2077 to replace its estimated 400,000 lines. In addition, Iowa,19 Indiana,20 Michigan,21 and Wisconsin22 have each recently changed laws to allow utilities to help families pay for customer-side LSL replacement.

Next steps on LSL replacement: Key questions for stakeholders

Taken together, federal and state developments could facilitate a shift in LSL replacement programs from a crisis-by-crisis, one-place-at-a-time approach to a more proactive and widespread strategy. Speeding the large-scale replacement of LSLs may create new economic and financial challenges and require creative solutions. For example, widespread and rapid LSL replacement would likely require increased funding beyond what is currently available from federal and state sources; new programs to coordinate with and provide financial assistance for homeowners to replace customer-side LSLs; and more workers, such as plumbers and other contractors, who will require training to acquire new skills but may also need to look for new work once LSL replacement is complete.

Over the coming months, our staff plans to research and convene with stakeholders on the many challenges and potential responses, focusing first on funding strategies and equitable solutions:

Funding strategies

Available federal funding for faster and more widespread LSL replacement is expected to fall short of the total cost. Although federal appropriations in late 2021 made $15 billion available for LSL replacement, this amount is less than half of the national cost estimates. Regionally, if the average LSL replacement cost matches the $7,700 cost in Benton Harbor,23 total costs will be at least $5.2 billion in Illinois, $3.5 billion in Michigan, $2.5 billion in Wisconsin, $2.2 billion in Indiana, and $1.2 billion in Iowa, based on lower-bound estimates of the number of LSLs in each state.24 Based on federal funding formulas, the portion of the federal $15 billion appropriation allocated to these five states will likely pay for roughly 10 percent of the total estimated costs in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and closer to 20 percent of the total estimated costs in Iowa.25 The funding gap raises several questions:

- What funding strategies are available to state and local governments as well as homeowners to pay for LSL replacement?

- What is the role of private financial markets in providing financing to governments and households for LSL replacement? Could existing markets be used, or will new markets need to develop? What kinds of incentives could encourage private financial markets to provide financing to governments or households? What barriers might impede private financing?

- What are the existing resources in the region to recruit and train the workforce needed for LSL replacement? How much new funding could be needed for workforce training and to increase workforce capacity or help workers transition to new work once LSL replacement is complete?

- How will large-scale LSL replacement affect the average cost of replacement? Will increases in demand for workers and materials drive up costs, or will widespread replacement programs create efficiencies that reduce per-line costs?

Equitable solutions

Given the concentration of LSLs in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, rapid LSL replacement holds the promise of advancing equity. However, there is also a risk that replacement strategies could amplify existing inequities. Situations where equity considerations may arise include 1) decisions about who is hired and trained to help replace LSLs; 2) the possibility that better-resourced water systems may replace LSLs many years, even decades, before water systems with fewer resources; 3) whether the ability to pay affects water systems’ decisions about which LSLs to replace first; and 4) when paying for LSL replacement requires borrowing, how differences in customers’ incomes and wealth and water systems’ resources affect borrowing costs. Initial questions related to equitable solutions include the following:

- Which funding strategies are more or less likely to disproportionately burden low- and middle-income communities?

- What are effective funding strategies to help customers who cannot cover the costs of replacing their customer-side line?

- What are ways to help ensure that smaller or less-resourced water systems have sufficient access to financial resources?

- Landlords do not generally consume the water at their properties but must often consent to and pay for LSL replacement, which benefits renters. Can funding strategies play a role in encouraging landlords to replace LSLs?

- What are the most effective ways to help ensure that meeting workforce needs for LSL replacement fosters a strong and inclusive economy?

Conclusion

The benefits of reducing lead exposure are vast: improved health, reduced health care costs, reduced risks of crime and incarceration, increased educational achievement and incomes, longer life spans, and improved quality of life.26

Our staff is committed to working with those already invested in LSL replacement to help facilitate positive change for communities in our region and throughout the nation. We invite people to write to us at CHI.Lead.Service.Lines.Project@chi.frb.org to share their insights on what it would take to rapidly replace LSLs and offer their own questions for exploration. We value varied views and hope a diverse set of stakeholders—from within and outside our region and from both small and large cities and water systems—will share their insights. Through our research and by synthesizing and sharing insights, we hope to help identify new windows of opportunity to overcome economic and financial barriers to rapid and widespread replacement of LSLs.

Notes

1 Final LCRR Economic Analysis, December 2020, 4-35. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-1769_content. Regulations.gov (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates at least 6.3 million LSLs); Final LCRR Economic Analysis, December 2020, 4-29. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-1769_content. Regulations.gov (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates total LSLs is approximately 9.3 million); and Lead Pipes Are Widespread and Used in Every State | NRDC (“12.8 million pipes that are known to be lead or may be lead”). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that drinking water can make up 20 percent or more of a person’s total exposure to lead. And that infants who consume mostly mixed formula can receive 40 percent to 60 percent of their exposure to lead from drinking water. Basic Information about Lead in Drinking Water | US EPA. Lead enters drinking water primarily through the corrosion of distribution system and household plumbing materials that contain lead. Final LCRR Economic Analysis, December 2020, 2-1. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-1769_content. Regulations.gov.

2 Health Effects of Lead Exposure | Lead | CDC (“No safe blood lead level in children has been identified”); Learn about Lead | US EPA (“Even low levels of lead in the blood of children can result in: Behavior and learning problems; Lower IQ and Hyperactivity; Slowed growth; Hearing Problems; Anemia”).

3 Dignam, Timothy, Rachel B. Kaufmann, Lauren LeStourgeon, and Mary Jean Brown. “Control of lead sources in the United States, 1970-2017: Public health progress and current challenges to eliminating lead exposure.” Journal of Public Health Management & Practice: JPHMP 25, no. Suppl 1 LEAD POISONING PREVENTION (2019): S13 at p. 8 (“Recent events involving lead-contaminated drinking water have highlighted the need to remove lead service lines; however, corrosion control water treatments remain an important component to lead-safe water.”); Introduction to Lead and Lead Service Line Replacement - LSLR Collaborative (lslr-collaborative.org) (“Even if your community has a water system with effective corrosion control and low drinking water lead levels, LSLs can contribute unpredictable and variable sources of exposure.”); Final LCRR Economic Analysis, December 2020, 5-207. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-1769_content. Regulations.gov (“The effectiveness of [corrosion control treatment] installation or re-optimization is uncertain”).

4 strategies_to_achieve_full_lead_service_line_replacement_10_09_19.pdf (epa.gov) provides examples of some cities that have proactive LSL replacement programs.

5 86 Federal Register 71574 (Dec. 17, 2021), 71575 (“minority and low-income populations appear to be disproportionately exposed to the risks of lead in drinking water”) Federal Register: Review of the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation: Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR); Data Points: the environmental injustice of lead lines in Illinois - Metropolitan Planning Council (metroplanning.org) (“65% of the [Illinois]’s Black and Latinx residents, and 42% of Illinois’ Asian-American and Native American populations, are living in communities containing 94% of the state’s known lead service lines”).

6 E2-UA-Economic-Impacts-from-Replacing-Americas-Lead-Service-Lines_August-2021.pdf, Tables 4 and 5.

7 Initial material inventory submitted to the Illinois EPA for 2019 report that Chicago (PWS) has 389,893 known lead service lines and 119,468 service lines of unknown material, Lead Service Line Information - Public Water Users (illinois.gov).

8 LSLR Financing Case Study: Madison, WI | US EPA.

9 Service Line Replacement Program – City of Flint. An exception is Lansing, MI, which replaced 12,000 LSLs between 2004 and 2016 without a public health emergency. Lead Information | lbwl.com

10 benton-harbor-sdwa-petition-20210909.pdf (nrdc.org)

11 Mi Lead Safe - City of Benton Harbor selects five firms to tackle lead service line replacements citywide, Accelerated work to begin in March (michigan.gov).

12 Congressional Research Service R46794 (June 22, 2021) at p. 13. Addressing Lead in Drinking Water: The Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) (congress.gov).

13 Section 50105 of 117 P.L. 58, 2021 Enacted H.R. 3684, 135 Stat. 429 at 1140, Text - H.R.3684 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act | Congress.gov | Library of Congress. In 2016, Section 2105 of the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act created this EPA grant program for reducing lead in drinking water across the country, including activities such as full lead service line replacement. PUBL322.PS (congress.gov).

14 Final LCRR Economic Analysis, December 2020, 1-3. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-1769_content. Regulations.gov (“more stringent sampling requirements in the final rule will better identify elevated lead levels, which will result in more systems replacing LSLs”).

15 117 P.L. 58, 2021 Enacted H.R. 3684, 135 Stat. 429, at 1400. Text - H.R.3684 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

16 86 FR 240 71574 (Dec. 17, 2021), 71574. Federal Register :: Review of the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation: Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR)

17 Mich. Admin. Code R. 325.10604f - Treatment techniques for lead and copper | State Regulations | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu).

18 415 Ill. Compiled Statutes 5/17 12(v). 415 ILCS 5/17.12 (ilga.gov).Illinois General Assembly - Full Text of HB3739 (ilga.gov)

19 567 Iowa Admin. Code 44.10(1)(a) (effective 5/18/2018) Iowa Admin. Code r. 567-44.10 - General administrative requirements | State Regulations | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu).

20 Ind. Code ch. 8-1-31.6 Indiana Code 2019 - Indiana General Assembly, 2022 Session

21 Mich. Admin. Code R.325.10604f(6)(b). Mich. Admin. Code R. 325.10604f - Treatment techniques for lead and copper | State Regulations | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu).

22 Wis. Stat. section 196.372(2) Wisconsin Legislature: 196.372

23 With a total estimated cost of $30 million and 3,900 to 4,300 LSLs, the average cost is between $7,000 and $7,700. Gov. Whitmer Visits First Lead Service Line Replacement Construction Site in Benton Harbor Since Call to Replace 100% of LSLs (michigan.gov) and Mi Lead Safe - City of Benton Harbor selects five firms to tackle lead service line replacements citywide, Accelerated work to begin in March (michigan.gov).

24 Estimated costs for each state equal the product of $7,700 multiplied by the estimated number of LSLs in the state according to Lead Pipes Are Widespread and Used in Every State | NRDC. Actual average costs may be higher or lower than those in Benton Harbor.

25 Authors’ calculations based on FY 2022 BIL - SRFs Allotment Summary (epa.gov).

26 For summaries of the harms of lead exposure and vast benefits of reducing lead exposure, see, for example, Prevention of Childhood Lead Toxicity | Pediatrics | American Academy of Pediatrics (aap.org); https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/08/hip_childhood_lead_poisoning_report.pdf; and Do Low Levels of Blood Lead Reduce Children's Future Test Scores? - American Economic Association (aeaweb.org).