As head of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, it is my pleasure to offer the Bank’s annual report for 2011. As the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve is charged by Congress with promoting price stability and maximum employment. This is often called our dual mandate and guides our decision-making in the monetary policy-making process.

I strongly advocated a highly accommodative monetary policy stance throughout 2011 and have continued to do so this year. The main essay in this annual report, titled “The Case for Accommodation,” explains my thinking on the subject. It also features answers to questions about policy that I frequently receive as I travel throughout the five states of the Seventh Federal Reserve District as well as the rest of the country. I hope you find the essay useful and thought-provoking in furthering your understanding of the work of this Reserve Bank and the Federal Reserve System as a whole.

As always, the success of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago depends on the important work of the talented people who make up our staff. I also would like to recognize the dedicated individuals who comprise our boards of directors, both here in Chicago and at our Branch in Detroit. A special note of thanks goes out to two Detroit Branch board members who retired at the end of the year: Tim Manganello, Chairman and CEO of BorgWarner in Auburn Hills, Michigan, who served for six years, five as chairman, and Mark Gaffney, President of the Michigan AFL-CIO, Lansing, Michigan, who served for a total of nearly 12 years on both the Detroit and Chicago Boards.

Together, these individuals contributed greatly to our goal of fostering financial stability in 2011, and as 2012 progresses we look forward to continued success in promoting the health and well-being of our U.S. economy.

Charles L. Evans

President and Chief Executive Officer

March 20, 2012

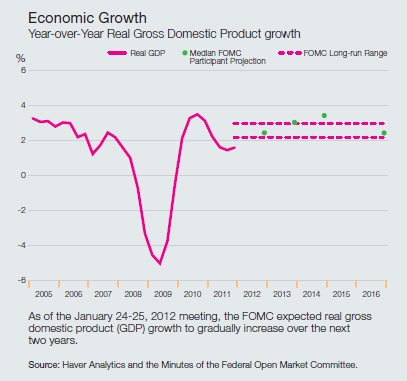

The U.S. economy continued to recover in 2011, though at a slower pace than in 2010. Real gross domestic product (GDP) grew only 1.7 percent over the course of the year and at an uneven rate: Growth was anemic during the first three quarters of the year and then picked up during the fall and winter months. Real GDP growth in 2012 is projected to be roughly on par with the potential rate of output for the economy, according to the median of the projections of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants.

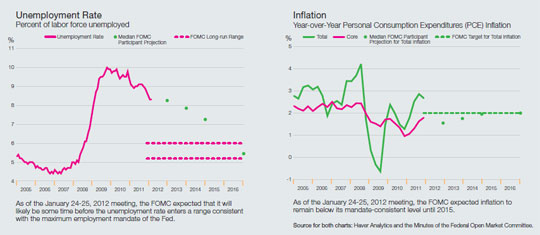

Over the course of 2011 and early 2012, the unemployment rate fell by nearly 1 percentage point. While this is welcome news, unemployment remains well above the range that encompasses the FOMC participants’ views of its longer-run natural rate. Furthermore, with growth expected to be only moderately above potential in the next few years, it could be some time before the unemployment rate declines to a level consistent with the employment side of the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate.

Looking at the price stability side of the mandate, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index ended the year 2.7 percent higher than in the fourth quarter of 2010. However, excluding volatile food and energy prices, core PCE inflation was up only 1.8 percent over the same period. With long-run inflation expectations stable and elevated resource slack continuing to exert some downward pressure on prices, the FOMC projections expect that inflation over the medium-run will be at or below the Committee’s long-run goal of 2 percent for total PCE inflation.

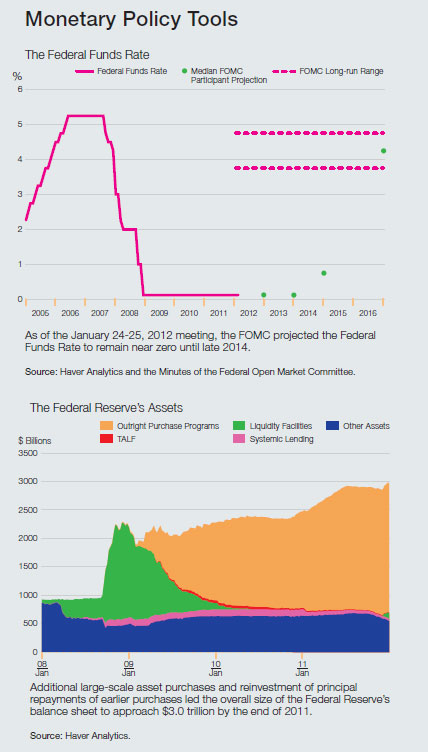

To support a stronger economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with its dual mandate, the FOMC expects to maintain a highly accommodative stance for monetary policy for some time. In particular, at its January 2012 meeting, the Committee indicated that it anticipates that economic conditions – including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run – were likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014.

The Economy

After rising at a moderate 2.4 percent annual rate of growth in the second half of 2010, real GDP grew at a sluggish annual rate of 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2011, reflecting declines in government spending and net exports, as well as weaker gains in consumption and investment. Growth in the second and third quarters of the year remained slow, coming in at annual rates of 1.3 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively. Growth increased to 3.0 percent in the final quarter of 2011, in large part due to an increase in inventory accumulation.

Business investment continued to improve in 2011, though not quite as strongly as in 2010. Purchases of new equipment and software continued to increase. For the first time in three years, the annual growth rate of investment in nonresidential structures was positive, boosted in part by a further increase in expenditures on drilling and extraction of petroleum and natural gas. In general, U.S. manufacturing is expanding – boosted by the recovery in the domestic automotive sector, as well as international trade. However, the recent weakness in Europe and other parts of the world remains a source of concern going forward.

Growth in consumer spending also slowed in 2011, with much of the weakness occurring in the first half of the year. The modest pickup in growth in the second half of the year came primarily from purchases of durable goods, as vehicle sales rebounded sharply following the spring supply chain disruptions that followed the natural disasters in Japan. In contrast, spending on nondurables and services was uncharacteristically weak. The housing market showed signs of improvement. For the first time since 2005, residential investment increased over the course of the year. However, the level of activity remains quite low.

The labor market showed signs of improvement in 2011. Additions to nonfarm payrolls averaged 153,000 new jobs per month – a total of 1.84 million jobs in 2011. This pace picked up in early 2012 as job gains averaged over 250,000 for the first two months of the year. Likewise, initial claims for unemployment insurance reached their lowest levels since early 2008, and the unemployment rate declined by over 1 percentage point to 8.3 percent in February 2012. There is still work to do, however: The economy remains at a net loss of 5.3 million jobs since the cyclical peak in December 2007.

Monetary Policy

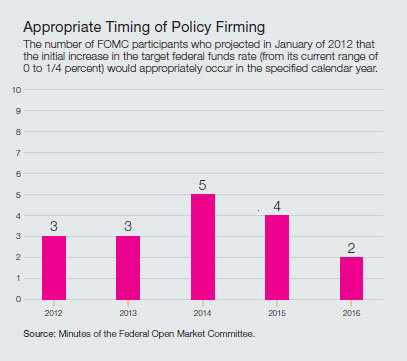

With a considerable amount of slack left in the economy, the FOMC left its traditional policy instrument, the federal funds rate, unchanged at a level between zero and 0.25 percent in 2011. However, as growth remained weak, in August the FOMC provided additional forward guidance on the path of the funds rate, altering the language in its policy statement from saying that economic conditions were likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an “extended period” to indicating that the length of the period would likely be through mid-2013. This period was then revised again in January 2012 to be likely at least through late 2014.

Nontraditional monetary policies also played a role in the FOMC’s response to weaker economic conditions in 2011. The FOMC’s purchases of $600 billion in long-term assets, announced at its November 2010 meeting, continued through the first half of the year until completion in June 2011. During the second half of the year, financial markets experienced some tightening, largely over concerns about European sovereign debt. To help reduce some of this strain and promote dollar liquidity, the Fed extended its swap facilities with the Bank of Canada, Bank of England, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and Swiss National Bank and lowered the rate for these transactions.

The FOMC also enacted a number of policies directed toward lowering longer-term borrowing costs. In September 2011, the FOMC began to re-orient its balance sheet to longer-term securities by selling $400 billion of Treasury securities with remaining maturities of three years or less and then purchasing an equal amount of securities with remaining maturities of six to 30 years. This process is expected to reach completion by June 2012. During the same meeting, the FOMC also announced that in order to support conditions in mortgage markets, it would reinvest principal repayments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in further agency MBS instead of in Treasury securities

*This essay reflects information available as of March 15 , 2012.

A Corporate Social Responsibility Council was created at the Chicago Fed in 2011 to take a holistic approach toward integrating ongoing work in the areas of economic and financial education, work force and supplier diversity and inclusion, and community and economic development and outreach programs.

ENVIRONMENTALISM

The Bank has worked aggressively toward creating a “green” culture by promoting environmental awareness and practices. Part of the process is pursuing for the Chicago Fed headquarters building a special certification that signifies it as a high performance green building in key areas of human and environmental health.

VOLUNTEERISM

The Chicago Fed actively encourages employees at Chicago headquarters and the Detroit and Des Moines offices to take part in community-based volunteer activities throughout the Seventh Federal Reserve District.

REGIONAL ECONOMIC OUTREACH

In addition to taking part in hundreds of speaking events and meetings throughout the Midwest in 2011, the Bank’s regional economists expanded their ongoing business roundtable discussions to include one in northwest Michigan and one focused on manufacturing with representatives from across the Midwest. Special conferences focused on rising farmland values, state budgetary stress, and the rise of electronic content in autos.

ECONOMIC EDUCATION

The Chicago Fed focuses on three programming areas: professional development for educators, in-kind and technical support for local education-based organizations, and experiential programs for students. In 2011, more than 200 educators attended sessions, and our educator-targeted blog received over 28,000 unique visitors.

FINANCIAL EDUCATION

Money Smart Weeks are the foundation of the Chicago Fed’s efforts to educate consumers to make informed choices about their personal finances. Each year, the Bank helps coordinate these Money Smart Weeks, in which roughly 1500 partner organizations put on more than 2000 free classes on a broad array of personal finance topics.

EMPLOYEE DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION/SUPPLIER DIVERSITY

COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

A variety of programs and research projects were carried out to address issues affecting economically disadvantaged and redeveloping communities as well as low- and moderate-income individuals throughout the Seventh District (see Highlights).

RESEARCHING ECONOMIC CONDITIONS

- Supporting the policy-making role of President Charles Evans, staff analyzed critical issues concerning national and regional economic policy, the economic recovery, and financial market developments.

- Researchers continued to analyze the potential role of job mismatch in explaining current weakness in labor markets.

- A new Insurance Initiative was established to analyze the role of the insurance industry in the financial sector.

- The new Industrial Cities Initiative focused on researching cities that have successfully maintained or improved their economic well-being after experiencing a major loss in their manufacturing base.

- Research continued on systemic risks to the economy and alternative models for derivatives clearinghouses.

- Best practices for error control in high trading environments were studied.

KEEPING BANKS SAFE

- Banking conditions are stabilizing. More banks are profitable, but the industry still has a considerable volume of problem loans to resolve.

- Credit Risk Management staff helped coordinate the closing of 13 distressed depository institutions located in the Seventh District.

- Leveraging lessons learned from the financial crisis, Supervision & Regulation (S&R) contributed to System efforts aimed at improving supervisory programs and processes.

- Continuing previous trends, examination events increased, yet S&R met all targets for delivering timely and accurate reports to the institutions we supervise.

- The impact of the Dodd-Frank Act (DFA) placed additional demands on supervisory resources. S&R added more than 100 people.

- The Chicago Fed gained supervisory responsibilities for 54 Savings and Loan Holding Companies (SLHCs) and nine Insurance SLHCs.

- The Act also called for enhanced prudential standards to be put in place for our largest organizations. The Chicago Fed established the Federal Reserve System’s Wholesale Credit Risk Center to serve as a resource for the System.

- The Seventh District contributed 26 people to the first and second Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR), a new DFA requirement to incorporate stress testing in the supervision of the largest banks.

KEEPING PAYMENTS SECURE

- All payment system business lines were able to manage costs to meet full cost recovery in 2011.

- The Customer Relations and Support Office (CRSO) continued to advance strategies to leverage the strategic and economic value of the FedLine network.

- District Cash performed well, adjusting staff levels to meet targets for productivity and work hours.

- District Cash realigned staffing levels and machine production shifts in response to technology-enabled productivity increases and exceeded the Cash Product Office’s performance targets.

- Chicago Cash Operations received one of its most favorable Treasury Compliance reviews.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS

- The Seventh District designed and led the System Incentive Compensation project, which produced a multi-disciplinary, horizontal review of incentive compensation practices at 25 large, complex banking organizations and helped formulate the DFA rule on this topic.

- Economic Research staff worked closely with the Board of Governors and other Reserve Banks on several key Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) related efforts.

- District staff participated in the Midwest Interagency Group, which brought together bank, insurance and securities regulators to begin dialogue related to oversight of diverse financial entities and to increase access and cooperation among agencies.

- Addressing community and economic development issues remained a priority throughout the year. One major effort was the Detroit Access to Credit for Small Businesses, which studied how changes in the location of bank branches and other financial service providers affect the availability of credit and access to banking services for small businesses.

- Money Smart Weeks were held in every state in the Seventh District and many cities outside the District, featuring roughly 1500 partner organizations bringing free educational seminars and events to tens of thousands of consumers.

- An iPad app was developed that serves as a useful tool for finding a wide variety of Federal Reserve System information.

These are welcome developments. But even the more optimistic forecasts see GDP growing only moderately above potential in the near term, and no one is expecting a surge in activity over the next couple years that would quickly close resource gaps. In fact, in the projections submitted in January, the central tendency of FOMC participants’ forecasts for the unemployment rate at the end of 2014 was still 6.7 to 7.6 percent. This is well above where most participants see the rate eventually stabilizing in the long run, which is between 5.2 and 6.0 percent. At the same time, the outlook for inflation is subdued, with most FOMC participants’ forecasts for increases in total PCE prices averaging roughly between 1 and 2 percent over the next three years. Furthermore, private sector long-run inflation expectations are quite well anchored, moderating this source of inflationary pressure.

Congress has mandated the Federal Reserve with setting monetary policy with the aim of achieving the dual goals of maximum employment and stable prices. In view of the unemployment rate outlook, I think it is clear that the Fed has fallen short in achieving its goal of maximum employment. And most FOMC participants see inflation at or below our target of 2 percent even in 2014. So on both elements of our dual mandate, we are missing our policy objectives.1

As the central bank in a democratic society, the Federal Reserve is accountable to the public. Accordingly, I believe we have to acknowledge that we are missing our policy mandates, and we need to describe the ways in which we will try to remedy this to achieve our objectives. So I have spent a good deal of time in my public discourse over the past year describing a policy strategy that I think will help us do a better job.

THE ECONOMY IN A LIQUIDITY TRAP

I believe that the disappointingly slow growth and continued high unemployment that we confront today reflect the fact that we are in what economists call a “liquidity trap.” In normal times, real interest rates — that is, nominal interest rates adjusted for expected inflation — rise and fall to bring desired saving into line with investment and to keep productive resources near full employment. This market dynamic is thwarted in the case of a liquidity trap. A liquidity trap occurs when desired saving increases a great deal but nominal interest rates fall to near zero and can go no lower. Real interest rates become “trapped” because they cannot become low enough to equilibrate saving and investment. That is where we seem to be now: Short-term, risk-free nominal interest rates are close to zero, and actual real rates are modestly negative, but they are still not low enough to return economic activity to its potential.

A liquidity trap presents a clear and present danger of a prolonged period of economic weakness — today that means a risk of repeating the experience of the U.S. in the 1930s or that of Japan over the past 20 years.

The important point for policy is that we need not resign ourselves to such an outcome. A large body of economic research concludes that economic performance can be vastly improved by employing monetary policies that commit to keeping short-term rates low for a prolonged period. Because of this, I have been advocating such a prolonged period of accommodation.

PROVIDING ACCOMMODATION WITHIN A BALANCED APPROACH TO MONETARY POLICY

While I believe we are in a liquidity trap and favor the prescription of prolonged accommodation, I recognize that my assessment could be wrong. Some have posited that we are in an economic malaise that reflects “structural factors” (such as a job skills mismatch) and that the economy today is actually functioning close to a new, more dismal productive capacity. If this scenario is true, then further monetary accommodation would lead only to rising inflation without much improvement in unemployment. In considering this possibility, I am mindful of the 1970s, when our failure to appreciate the changing structure of the economy led to an overstimulative policy and eventually to stagflation.

Although I do not find this structural impediments scenario compelling, as a prudent policymaker, I must at least consider it as a possibility. Accordingly, I favor a monetary policy strategy that balances the two risks of dismally slow growth on the one hand and rising inflation on the other.

The Fed could sharpen its forward guidance by pledging to keep policy rates near zero until one of two events occurs. The first event would be if the unemployment rate moved below 7 percent. An unemployment rate below this threshold would represent enough meaningful progress toward the natural rate of unemployment that it might be time to lessen policy accommodation.2

The second event prompting higher rates would be if inflation rose above a particular threshold even if the unemployment rate remained above 7 percent. This trigger is a safeguard against the possibility that we are wrong and the natural rate of unemployment is higher than 7 percent. If this were so, then the low-rate policy would generate an unexpected increase in inflation, and the trigger would cause us to exit from what would now evidently be excessive policy accommodation. We would not have the desired reductions in unemployment, but then again, monetary policy could do little about it.

I believe that this inflation-safeguard threshold needs to be above our current 2 percent inflation objective. This is consistent with the theoretical work showing that extraction from a liquidity trap requires the central bank, if necessary, to allow inflation to run higher than its target over the medium term. My preferred inflation threshold is a forecast of 3 percent over the medium term. This seems to me to be a risk we should be willing to accept. We would suffer some net policy loss if the expected gains in employment did not materialize. But we certainly have experienced inflation rates near 3 percent in the recent past and have weathered them well. And 3 percent is not even close to the debilitating higher inflation rates we saw in the 1970s or 1980s. Nor is it high enough to unhinge long-run inflation expectations.

Let me also emphasize that under this policy proposal, inflation reaching 3 percent is only a risk and not a certainty. Indeed, simulations of standard models suggest that inflation is likely to remain below 3 percent, even under a policy of extended monetary accommodation.

For monetary policy to be most effective, communication must be both clear and consistent. Furthermore, as a central bank in a democratic society, we have a responsibility to articulate the FOMC’s views about the goals for monetary policy and the strategies it will employ to achieve those goals.

I have tried to be clear and open in explaining my policy views to the public, giving my messages about the economic outlook and my preferred policy reaction in numerous speeches and press interviews over the past year. I have received thoughtful and sometimes tough questions at these speaking engagements. Answering these questions has offered me another channel to explain and expand on my thinking. What follows is a sampling of those questions and my edited responses to them, culled from the answers I gave at the time and supplemented with content from speeches covering the topic. The answers have also been updated where necessary to reflect current economic and policy conditions.

THE OUTLOOK FOR THE U.S. ECONOMY

How do you make the argument that the economy needs more accommodation when it looks like it is improving?

We have been disappointed so many times since the expansion began. I am at the point where the normal flow of monthly data is not instrumental in my views on the economy. I had been more optimistic. In 2010, I thought we would achieve escape velocity. It did not happen. In 2011, we saw more of the same slow growth, and real GDP growth in the first half of the year was revised down. The amount of resource slack in the economy is still very large. My forecast for this year is about 2-1/2 percent growth, rising to about 3 percent in 2013. That’s not enough to make substantial progress on the labor market and to close the output gap.

If we don’t do some of the things that you’re prescribing, where does the U.S. economy go?

I hope I’m wrong. I hope the economy takes off and we achieve escape velocity. But if we don’t, if the unemployment rate stays high, there are a large number of people whose skills are going to diminish. Their opportunities aren’t going to be very strong, and that’s going to reduce the potential of our economy to grow. This occurs because growth depends not only on capital accumulation and technology, but also on the skill composition of the work force. If we’re not using the work force efficiently and up to workers’ skill levels, we’re not going to produce as much. That would translate to lower living standards for everybody. So we need to get living standards up through higher growth.

MONETARY POLICY STRATEGY

Can you describe your monetary policy strategy?

Policymakers must ask whether their forecasts are consistent with their medium- and long-term policy objectives and, if not, what then is the best response for monetary policy to influence the trajectory of the economy and inflation in order to meet the FOMC’s objectives. In essence, this boils down to looking at how far inflation and unemployment are from the values we see as being consistent with our long-run policy objectives and weighing the relative deviations from our goals, both today and also along the prospective paths over which these deviations are likely to close over time under various policy options. This is often referred to in the macroeconomics trade as flexible inflation targeting.

A central banker who favors a conservative approach to monetary policy can still value deviations in unemployment from the natural rate of unemployment equally with deviations in inflation from its target.3 Accordingly, an inflation rate of 5 percent versus an inflation goal of 2 percent presents this policymaker with an equal-sized loss as a 9 percent unemployment rate versus a conservative estimate of 6 percent for the natural rate of unemployment. There also is an immediate corollary: If you aren’t as riled up over 9 percent unemployment as you would be over 5 percent inflation, then you either put even less weight on unemployment misses in your loss function or you think that the natural unemployment rate is substantially higher than 6 percent.

Given how poorly we are doing in meeting our employment mandate, I argue that the Fed should seriously consider actions that would add very significant amounts of policy accommodation. Such further policy accommodation would increase the risk that inflation could rise temporarily above our long-term goal of 2 percent. But I do not think that a temporary period of inflation above 2 percent is something to regard with horror. I do not see our 2 percent goal as a cap on inflation. Rather, it is a goal for the average rate of inflation over some period of time. To average 2 percent, inflation could be above 2 percent in some periods and below 2 percent in others. If a 2 percent goal was meant to be a cap on inflation, then policy would result in inflation averaging below 2 percent over time. I do not think this would be a good implementation of a 2 percent goal.

You get tremendous push-back from your colleagues when you say, “It’s OK for inflation to run a little bit hotter for a period of time.” What’s your reaction?

I think that’s what flexible inflation targeting means. Don’t forget that the unemployment rate is 8-1/4 percent and the natural rate of unemployment is much closer to 6 percent. So, we need to evaluate our policy losses and keep both goals in mind when we formulate policy.

But didn’t we try that in the 1970s without success?

I have some worry about repeating the 1970s. What central banker wouldn’t? But the circumstances today are really quite different. In terms of sustained, higher inflationary expectations, the situation is much different now. In the 1970s, you had high wage growth and a wage-price spiral. Prices would go up, workers would demand that wages go up to compensate for rising prices, and the two would keep spiraling upwards. I don’t believe today anybody expects that wages are going to increase to the extent that it’s going to propel inflation or inflation expectations higher. The state of the labor market is that many people are looking for jobs, thereby creating downward pressure on wages. And the thing is we’re always tempted to fight the last war, which in my view is what the 1970s experience represents. I’m much more worried about repeating the 1930s experience or Japan’s experience of these past 20 years.

Can you explain why you thought the Fed should have done more when you dissented from the consensus viewpoint twice at FOMC meetings in late 2011?

I think the economy needs more accommodation. I think the current unemployment rate is unacceptably high. We should be much closer to 6 percent or less than that. That’s where I think the natural rate of unemployment currently is. So I think we should be doing as much as we can to get there. There is strong accommodation already in place. We’ve done a lot already, but we are a long way from achieving our goals. Clearing up timing questions would provide even more accommodation.

You have mentioned the desire for a clear framework for setting monetary policy decisions. What does that mean for stating both explicit inflation and unemployment targets?

I strongly supported the adoption of a framework statement by the FOMC that contains both of these elements. I think a framework should include clarifying an explicit inflation objective, as we recently did in stating a 2 percent target. On the unemployment side, I think it’s very important that we have some clarification of what’s meant by maximum employment, but quantifying a particular goal for that is much more difficult. Maximum employment is affected by so many factors outside the scope of monetary policy, and those factors change over time. But we can provide estimates. FOMC participants’ latest projections for the rate unemployment would converge to in the absence of further shocks to the economy are 5-1/4 to 6 percent. So our target should be in that range.

PREFERRED FUTURE COURSE OF MONETARY POLICY

So you think we’re going to grow at or even a little bit above trend, but you still think the Fed should take action. What action should it take at this point?

Growth of say, 3 percent, would be a little bit above trend but not nearly enough to make large improvements in the labor market. So I favor being more aggressive in applying accommodative monetary policy. The first step I would take is to clarify the conditions under which we would contemplate removing accommodation. I would say that we will continue to be accommodative as long as the unemployment rate is above 7 percent. We’re pretty far from that right now. Seven percent is above what I think is a sustainable unemployment rate. When we get to 7 percent, we’ll look at how we’re doing. We might decide to provide even more accommodation.

This is all as long as inflation remains contained. By “contained,” I mean inflation potentially above our 2 percent target, but certainly no more than 3 percent over the medium term. If we find that we are bumping up against 3 percent, that would tell us that things aren’t proceeding the way I expect; maybe there’s another impediment and we’re running into structural problems. But I’d like to at least test that.

With all the accommodation already in place, how would additional stimulus encourage business spending and investment?

I think it’s important to get the incentives right. Businesses and households need to reach the point where they find it in their best interests to engage in slightly more risk-oriented investment, so that businesses actually start thinking about growth opportunities. If we keep applying accommodation, we’ll eventually tip the scales on the question of incentives so businesses will want to undertake more investment.

At what point would the FOMC consider additional asset purchases?

I think that the state of the economy is such that, all else being equal, it would be a good idea for the Fed to undertake more asset purchases. But before doing so, I think we should first clarify our language on forward guidance. Then we should monitor very closely what progress is being made towards our goals, asking, “How quickly is the economy accelerating and bringing unemployment down? How is the economy responding?” And then, only if we think that there’s not enough progress being made, I would consider providing additional accommodation through more asset purchases.

Can you explain how more asset purchases would help lower the unemployment rate or create growth?

These purchases are aimed at directly influencing longer-maturity interest rates; lower long-term rates, in turn, should stimulate spending by households and businesses. The purchases also play an important and useful communications role — they signal our commitment to keeping short-term rates low for an extended period of time.4

Consider a metric for interest rates, the well-known Taylor Rule, which captures how monetary policy typically adjusts to output gaps and deviations in inflation from target. At the time of our second set of asset purchases (in November 2010), the Taylor Rule would have called for the federal funds rates to be something like –4 percent, well below the zero lower bound at which the funds rate is still trapped. Our large-scale asset purchases have provided additional stimulus, but by most estimates, not enough that it would be equivalent to bringing the federal funds rate down to the Taylor Rule prescriptions.5 So, in the absence of other accommodative policy actions, there is an argument for having another large-scale asset purchase program.

In July 2011, FOMC Chairman Ben Bernanke reconstituted the FOMC Subcommittee on Communications and asked it to study proposals to increase monetary policy transparency. I served on the Subcommittee, which was chaired by Governor Janet Yellen and also included Governor Sarah Raskin and Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser. The Subcommittee worked on two major communications initiatives that were adopted by the entire FOMC and rolled out to the public at the January 2012 FOMC meeting. The first was a framework statement of our monetary goals and strategies, and the second was the publication of FOMC participants’ projections for the future path of appropriate policy. I believe that these latest communications efforts are an important step in further increasing our transparency and accountability to the public. Importantly, they reaffirm our commitment to both legs of our dual mandate and they further describe the ways in which we will seek to achieve these objectives.

THE FRAMEWORK STATEMENT

The framework statement clarifies how the FOMC interprets its statutory responsibilities for facilitating maximum employment and price stability, in terms of measurable and achievable economic goals over the longer run. We say that the FOMC considers a rate of inflation of 2 percent over the long run as being consistent with the price stability leg. There are two important ingredients: Our explicit inflation objective is 2 percent; and this is to be achieved over the long run. As recently as 2005, many FOMC participants preferred to describe a range of inflation outcomes as being consistent with our inflation mandate instead of stating it as a single number. Our current statement narrows our objective to 2 percent. It also presents this as an average that we aim to achieve over the long run, in recognition of the obvious fact that inflation may deviate from this goal from time to time owing to economic challenges, conflicts in achieving the dual mandate objectives, and difficulties in the policy transmission channels.

The statement also notes that maximum employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors, which are difficult to measure and may change over time. Hence, we cannot and do not specify a fixed, time-invariant goal for it. But FOMC participants can provide their current assessments of goal variables related to the achievement of maximum employment. We do so using the central tendency of FOMC participants’ projections for the rate that unemployment would converge to in the absence of further shocks to the economy. As of January 2012, this rate is 5-1/4 to 6 percent.

The statement also indicates that policy will seek to mitigate deviations in inflation and unemployment from these longer-run goals and addresses the weighting of relevant costs and benefits when trying to close these gaps. Namely, if the policy prescriptions for achieving the inflation and unemployment goals are in conflict, we will take a balanced approach in promoting the economy’s return to each goal, taking into account the size of the deviations and the relative speeds at which convergence can be expected.

Just about every major central bank around the world publishes something akin to such a framework statement. In one way, the Fed’s is different because, unlike other countries, we have a dual mandate, so our framework explicitly addresses goals for both inflation and the real side of the economy (as reflected in employment). But just about every central bank with a single price stability mandate also says that it will avoid undue disruptions to the real side of the economy when pursing its inflation goal. Indeed, some are quite clear about following a flexible inflation targeting strategy.

POLICY PROJECTIONS

The forecasts for growth, the unemployment rate, and inflation that FOMC participants have been submitting since 1979 have always been conditioned on each participant’s views of the future path of policy most likely to foster outcomes consistent with our dual mandate responsibilities — what we refer to as the appropriate path for policy. As of January 2012, our quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) now includes the projected paths for the federal funds rate and qualitative information about the balance sheet that make up these views.

I believe this move significantly enhances policy accountability. For example, suppose inflation were running higher than we would like, and the economic projections in the SEP showed it coming down over the next couple of years. In the absence of policy projections, the public would not know whether the FOMC thought inflation would simply come down on its own or whether it thought that a monetary tightening would be required to reduce inflationary pressures. The inclusion of participants’ policy projections will help communicate such judgments.

Furthermore, households and businesses will be able to make better informed decisions if they have a clearer notion of future policy rates; the potential for reduced uncertainty could also lower the risk premium embedded in longer-term interest rates. Now, clearly, our forecasts of what rates are going to be three years from now will often be wrong — and sometimes by a good deal. Some say this means our projections are worthless or, even worse, will cause people to underweight interest-rate risk in making economic decisions. I disagree. The accuracy of the early forecasts we write down is not as important as the fact that the public can observe how these forecasts change over time. As the economy is hit by shocks or the data come in contrary to expectations, we will update our forecasts for both the economic variables and the policy rate. As we do, households and businesses will be able to learn more about the monetary policy reaction function. And this knowledge will help them make better informed decisions.

Another criticism we heard the day the projections were published was that they seemed to be inconsistent with the FOMC policy statement released a couple of hours earlier. The statement indicated that the Committee thought economic conditions were likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014, but six of the 17 policy projections anticipated a fed funds rate of 1-1/2 percent or higher at the end of that year. Well, by the next day, the markets had figured it out; the projections are made by all FOMC participants, while the statement reflects the policy views agreed upon at the meeting by the voting members of the Committee. We all come into the meeting with our own projections, but we then do have a real debate: All of the participants exchange ideas and argue points of view, and then the voters on the Committee come to a consensus and make a collective policy decision. The information regarding the federal funds rate in the SEP does not substitute for this formal decision of the voting members of the FOMC.

That said, the diversity of views is a fact of life. Policymakers may well make different judgments about the appropriate stance of monetary policy in the particular economic circumstances of the moment. These communications initiatives cannot eliminate these differences of opinion. But they further discipline the parameters of our discussions, clarify the judgments that underlie our policy decisions, and enhance transparency and the public’s ability to evaluate current monetary policy and compare it with alternative approaches.

Senior Vice President and Senior Research Advisor Spencer Krane and Economist and Senior Policy Specialist Ellen Rissman contributed to the development of these essays.

First Vice President Gordon Werkema leads the Federal Reserve office that operates the electronic FedLine network, which financial institutions use to access Federal Reserve Bank payment services – more than 71 million payments daily worth almost $4 trillion. Werkema also oversees national sales and marketing of these services.

First Vice President Gordon Werkema leads the Federal Reserve office that operates the electronic FedLine network, which financial institutions use to access Federal Reserve Bank payment services – more than 71 million payments daily worth almost $4 trillion. Werkema also oversees national sales and marketing of these services.

Consumers, businesses, retailers and governments – as well as the depository institutions that service them – do not have to look too far to see that the payment system is changing rapidly. Non-bank service providers have been jumping into the payment service business. The choice of payment instruments and channels keeps growing. Payment options – including prepaid cards, debit cards, credit cards, stored-value systems, smart phone apps, checks and cash – bombard consumers. And financial incentives abound for service providers, prompting them to steer consumers toward certain types of payment methods and away from others.

With its finger on the pulse of the U.S. payment system, the Reserve Bank Financial Services team is facing these changes head-on. Our national sales and marketing teams closely monitor payment activity and customer needs, and the Board of Governors and various Reserve Banks publish useful research documenting changes in the use of different payment instruments. We also stay very close to the industry by partnering with other payments organizations. For example, this past year we collaborated with NACHA to establish formats, rules and procedures for international ACH payments.

Overall, what we continue to learn from our own efforts and through industry partnerships is that large non-bank companies and service providers – as well as smaller start-up companies – are innovating rapidly in payment services and competing to provide the best solutions for end-users. This drive to innovation reflects the market-driven approach to payment services in the U.S., where multiple banks, service providers, technology companies and the Reserve Banks are in the competitive mix.

Through these periods of change, the Reserve Banks have stood firm as the foundation of the U.S. payment system. For almost 100 years, the role of the Reserve Banks has been to operate a national payment clearing and settlement network, guided by the goals of integrity, efficiency and accessibility. We have not strayed from these goals, and we stand committed to helping financial institutions maintain stability, both in our role as system operator and as an industry thought leader. Summarized below are some accomplishments in 2011 that highlight this commitment.

INTEGRITY

A key attribute of payment system integrity is operating reliable and secure networks, with effective risk management and controls, especially in systemically important systems.

In recent years, the commitment to integrity has expanded to include a focus on resilience and data security, including preparedness for business disruptions such as malicious attacks, natural disasters or network outages. The Federal Reserve Banks are strategically investing in technology and infrastructure designed to enhance security and reliability. We also have initiatives underway to modernize our funds transfer and securities-processing platforms, check, ACH and electronic access. These improvements will scale our systems for the future processing needs. Enhancing the security of our payments network is requiring ongoing investment in industry-leading approaches for identity and access management, encryption, and intrusion detection.

EFFICIENCY

The Reserve Banks continue to focus on maximizing efficiency within our operations by encouraging even greater use of electronic clearing. We also believe some of the greatest opportunities lie in facilitating straight-through processing for financial institutions and their customers, both business and consumer. Over the past several years, the Federal Reserve Banks have worked with the industry to identify barriers to moving business-to-business (B2B) transactions to electronic payments. We have taken a number of actions to address these obstacles with enhancements to virtually all of our payment services. Some of the key advances include more sophisticated risk management and electronic data interchange (EDI) related services for ACH as well as implementation of an updated Fedwire funds transfer format that supports notification services and remittance information using an internationally recognized format standard. Educating financial institutions and corporations about these innovations and how they address B2B payment requirements is important.

Opportunities for greater clearing speed and efficiency exist for ACH payments as well, both for domestic and international payments. The Federal Reserve Banks’ FedACH® SameDay Service introduced a significant change to ACH debit originations and helped to set in motion the industry effort to design an expedited ACH credit origination clearing and settlement model. Same-day clearing puts ACH on par with electronic check, debit and credit transactions from a settlement timing perspective, but at a lower clearing cost and with less risk. With the growth of cross-border commerce, tremendous opportunities also exist to speed international payments, reduce exceptions, lower costs and provide greater certainty and transparency to international payments clearing. Today, the Reserve Banks’ FedGlobal® ACH Payments network provides low-cost ACH credit payments clearing to 35 countries, as well as debit payments to Canada, with expansion of the network under consideration.

ACCESSIBILITY

Accessibility is the ability of all depository institutions to use Fed services. We offer services across our entire product suite that are competitively priced and help ensure widespread access. Our FedLine® services provide flexible options so that financial institutions can access the types of services they need at a price they can afford. Customers who aren’t able or choose not to invest in sophisticated payments capabilities internally can take advantage of an array of clearing, risk management, information and reporting services we offer. This fuels a competitive marketplace for payments services and benefits end users.

The Reserve Banks supplement our operator role with research and development-like events that benefit the industry at large. For example, the Chicago Fed last year hosted a symposium on Immediate Funds Transfer (IFT) for general-purpose payments. It highlighted systems that are up and running in other countries and asked whether IFT-like attributes would be beneficial for the U.S. payments system as well. We also sponsored a conference on remote payments fraud, which brought industry participants together to discuss strategies to help reduce this type of fraud.

Part of our role as a thought leader in the payments system is to develop meaningful partnerships with various industry associations, system operators, bankers, academics, and legislators, as well as our own System Product Offices. Through forums such as focus groups and conferences, we can keep in close touch with industry developments about how to deliver better customer service.

As we look beyond the current state of change, the Fed finds itself at a crossroads. Our vision is to understand new ways that our payment and clearing network can bring benefits to all end-users of the payments system – in the U.S. and globally. We gain this understanding only through partnership with the private sector, as we have always done. In doing so, we commit to consider the needs of the smallest credit union to the largest bank. In that way, we will continue to be the foundation of the U.S. payment system.

Contributing to the development of this essay were Kirstin Wells, Assistant Vice President, Financial Markets Group, and Cyndi Pijarowski, Assistant Vice President, Customer Relations and Support Office.

Portions reprinted by permission of the Association for Financial Professionals. Excerpted from April 2012 Exchange. Copyright 2012. All rights reserved.

1At the January 2012 FOMC meeting, the Federal Reserve for the first time decided on an explicit inflation target—2 percent as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures. The FOMC did not specify a fixed goal for maximum employment, but noted that the central tendency of FOMC participants’ most recent estimates for the rate of unemployment consistent with this goal is 5-1/4 to 6 percent. See “Recent FOMC Communications Initiatives”.

2Note that if inflation fell to 1 percent (below our 2 percent objective) while unemployment improved to 7 percent, then tightening policy at this point would run counter to the achievement of both our employment and price stability objectives.

3For more information, see Charles Evans, 2011, “The Fed’s Dual Mandate Responsibilities and Challenges Facing Monetary Policy,” speech delivered on September 7 at the European Economics and Financial Centre, London, United Kingdom.

4Charles Evans, 2011, “Making Sense of Monetary Policy,” speech delivered on May 19 at the Global Corporate Treasurer Forum, Chicago, Illinois.

5 Charles Evans, 2011, “The Fed’s Dual Mandate Responsibilities: Maintaining Credibility during a Time of Immense Economic Challenges,” speech delivered on October 17 at the Michigan Council on Economic Education, Michigan Economic Dinner, Detroit, Mich.