Closing the Racial/Ethnic Gap in Refinancing in Chicago

In this blog post, we explore the widening of Chicago’s racial/ethnic gap in refinancing (refi gap) when mortgage interest rates fell to a historical low during the Covid-19 pandemic. Understanding why borrowers in majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods fell behind at a financially opportune time offers insights into how improving access to mortgage interest savings can strengthen opportunities for wealth accumulation.

Generally, when interest rates decline and stay low for several weeks or longer, borrowers have the chance to save money by refinancing into mortgages with lower monthly payments. For example, in 2020 (when offer rates on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages averaged 3.11%), 11% of borrowers nationwide lowered their payments by an average of approximately $280 per month. However, as figure 1 shows, the refi gap was larger in 2020 than in 2019, when rates were nearly a percentage point higher and fewer borrowers refinanced. The widening of the refi gap between 2019 and 2020 has contributed to greater racial disparities in the cost of mortgage credit, as Black and Hispanic borrowers are less likely to take advantage of lower interest rates than their White counterparts. Some estimates suggest that annual interest savings could be about $600 to $700 for Black and Hispanic borrowers if they refinanced at the same rate as White borrowers during refinancing booms.1

1. Refinancing rates among active loans in January 2019 and January 2020, United States

| Borrower race/ethnicity | January 2019 to October 2019 | January 2020 to October 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| White | 3.2 | 11.6 |

| Black | 2.5 | 6.2 |

| Hispanic | 3.2 | 8.9 |

| Asian | 3.2 | 13.6 |

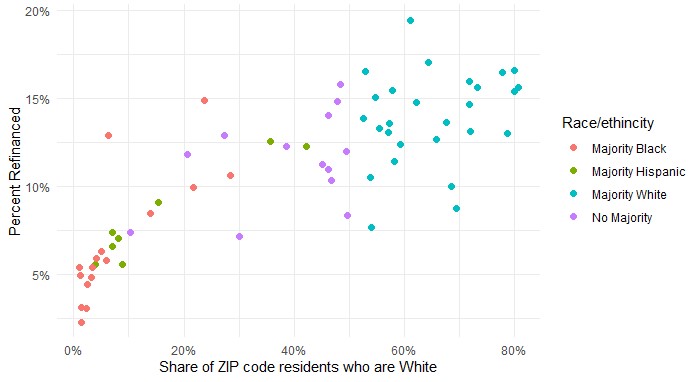

In Chicago, between January 2020 and December 2021, as offer rates on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages declined to a historical low and hovered in a low range, we estimate that approximately 11% of borrowers (or just over 17,000) refinanced their mortgages.2 But, as figure 2 shows, the likelihood of refinancing between January 2020 and December 2021 increases with a neighborhood’s share of White residents, owing in part to higher rates of refinancing among White borrowers relative to their Black and Hispanic counterparts. Moreover, consistent with the national estimates shown in figure 1, figure 2 also reflects the widening of the refi gap documented in the literature.

2. Refinancing rates, January 2020 to December 2021, Chicago

Sources: Equifax Credit Risks Insight Servicing, Black Knight McDash Data, and IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota, https://www.nhgis.org/.

Several factors likely account for these neighborhood-level differences along racial/ethnic lines:

1. Federal forbearance policies provided an alternative way to reduce mortgage payments during the Covid-19 pandemic. In particular, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act allowed borrowers to enter forbearance and temporarily suspend mortgage payments by attesting hardship to their lender. Many borrowers obtained relief for up to 18 months from this policy, often without damaging their credit. This relief was especially important for Black and Hispanic borrowers and their communities, who experienced worse health and employment outcomes during the pandemic and thus higher rates of mortgage non-payment, one indicator of financial distress. However, borrowers must exit forbearance to refinance, which involves resuming payments and paying loan origination costs.

2. Differences in risk factors along racial/ethnic lines shape refinance opportunities. On average, Black and Hispanic borrowers have lower credit scores, higher loan-to-value ratios, lower incomes, and less liquid wealth than White borrowers. So, when rates fall, Black and Hispanic borrowers’ risk profiles are more likely to limit their refinance opportunities, even though in many instances, lower payments would reduce their credit risk.3 In addition, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Black and Hispanic borrowers were also more likely to experience income loss, such as by losing a job or reducing their working hours. In general, measures of creditworthiness contribute to lower rates of refinancing among Black and Hispanic borrowers because they inform lenders’ decisions about whether to offer refinancing and at what cost to the borrower. At the same time, Black and Hispanic borrowers may also hold back on applying for refinancing if they believe that lenders will reject their applications based on their credit profiles or if they cannot pay for the upfront costs of refinancing their loans.

3. The home appraisal process may systematically undervalue the homes of Black and Hispanic borrowers when they try to refinance. For both purchases and refinancing loans, the appraisal—that is, the estimated market sale price of a home—is an important input into mortgage underwriting. It affects whether borrowers obtain mortgage credit, the interest rate they pay, and other costs of the loan. Despite a legal requirement that prohibits appraisers from considering the race/ethnicity of the borrower or their neighborhood in the appraisal process, numerous examples of undervaluation of homes owned by Black Americans have been brought to light (for example, see this article). Furthermore, in recent years, there has been an uptick in litigation about undervaluation in appraisals, thanks in part to greater efforts among fair housing centers to help people who believe they have been victims of housing discrimination (Abraham, forthcoming).4 Finally, studies that more systematically analyze home appraisals find that Black and Hispanic applicants are more likely to receive an appraisal value that is lower than the contract price in purchase transactions, one indicator of undervaluation in the appraisal process.

4. Other housing or mortgage market factors, including those that are “race neutral,” may disproportionately contribute to frictions or barriers to refinancing for Black and Hispanic borrowers. For example, there is some evidence that lenders tightened standards in the fall of 2020. In addition, during refi waves, capacity constraints among lenders can lead them to prioritize higher-value mortgages, such as those in neighborhoods with higher home values or lower-credit risk borrowers. Lenders may also increase the markups they charge borrowers. Information frictions may also reduce opportunities for Black and Hispanic borrowers, including more-limited channels for learning through social networks. And lender discrimination—that is, lenders treating borrowers differently because of racial/ethnic animus, borrower characteristics unrelated to creditworthiness in underwriting, or both—may inhibit or deter Black and Hispanic borrowers from taking advantage of refinancing opportunities.

5. Chicago’s long-standing residential segregation along racial/ethnic lines shapes neighborhood-level differences in refinancing during refi booms. Across many measures of segregation, Chicago has ranked at or near the top among major U.S. cities for many decades.5 When the refi gap widens during refi booms, residential segregation means that the stimulative effects of refinancing to household consumption are uneven across neighborhoods, as are the mortgage interest savings and the potential for building housing wealth. And because lower payments typically lead to greater housing stability, neighborhoods with more borrowers missing out on refinance opportunities are less likely to experience the benefits of housing stability. Finally, features of neighborhoods themselves—home values, employment opportunities, residents’ social capital, the presence of and programs offered by financial institutions, and much more—may limit refinancing opportunities for Black and Hispanic borrowers.6

Estimates in figure 3 show that the approximate aggregate potential savings to borrowers living in neighborhoods with different racial/ethnic majorities can be quite large. Specifically, the estimates highlight that if Chicago’s Black- and Hispanic-majority neighborhoods had the same average refinancing propensity as its majority-White neighborhoods, additional mortgage savings could be up to $340,000 per month in the aggregate for those ZIP codes, or equivalently about $90 to $110 per month per borrower. Because these estimates require many stylized assumptions, they should be interpreted as indicating a rough order of magnitude that conveys the scope of dollars at stake rather than a precise estimate of the savings that would result. Actual savings would differ, depending on the actual reduction in the interest rate borrowers receive, how much they refinance (including any cash-outs), specific non-interest rate features of the old versus new mortgage contract, the fees paid to refinance loans, and possible foregone tax savings from paying less interest, among other factors.7 Comparing our results against those of other studies that more precisely estimate actual savings suggests that our estimates can be viewed as a reasonable approximation.

3. Aggregate potential savings from refinancing by borrower ZIP Code, Chicago

| Borrower’s ZIP code | Median monthly savings if refi at rate of majority-White ZIP codes ($) | Aggregate monthly savings if refi at rate of majority-White ZIP codes ($) | Number of borrowers | Percent refinanced between January 2020 and December 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majority White | 89 to 111 | – | 63,578 | 14.7 |

| Majority Black | 90 to 105 | 180,000 to 210,000 | 26,312 | 7.1 |

| Majority Hispanic | 88 to 105 | 111,056 to 132,405 | 21,028 | 8.7 |

| No Majority | 93 to 114 | 65,100 to 79,800 | 33,310 | 12.6 |

Addressing the widening of the racial/ethnic refinance during periods of low interest rates presents an important opportunity for improving borrowers’ and neighborhoods’ financial stability. Refinancing into lower rates is important for household wealth-building because it allows borrowers to reduce their interest payments and save more, among other benefits. However, broadening the opportunity that arises when interest rates fall remains a complex endeavor and there remains a lot to learn, especially in cities like Chicago. For one, the available evidence provides little direct guidance on the design of effective borrower-level interventions, including by finding weak evidence of the efficacy of certain types of marketing campaigns. Second, although more scalable solutions can reduce borrowers’ inertia in whether and when to refinance, there may be unintended costs to these solutions. For example, mortgage contracts with automatic refinance features or broadening participation in streamlined refinancing programs can offer scale but may also increase mortgage costs or introduce new consumer financial protection issues. Third, it may be that the most effective policy interventions operate through channels outside of the mortgage market, such as improvements to borrower credit quality arising from programs that improve employment stability or strengthen legal protections against labor market discrimination. Finally, there is little to no evidence on the role and design of local solutions, which may be important if local barriers are unique, such as specific language barriers or the level of trust toward financial institutions in Black and Hispanic communities.

Notes

1 In the aggregate, Black and Hispanic borrowers are estimated to save over $800 million per year if they refinance at the same rate as White borrowers during low interest rate periods. This same study also suggests that differences in refinancing behavior are the primary driver of mortgage interest rate inequality by race or ethnicity.

2 Consistent with other refi booms, most borrowers who would benefit financially from refinancing do not do so. The focus of this post is on the refi gap rather than on why borrowers more generally “leave money on the table.”

3 Indeed, streamlined programs that refinance borrowers with limited credit documentation and underwriting recognize that Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae already hold the credit risk, so allowing borrowers to lower payments can decrease credit risk.

4 Heather Abraham, “Appraisal discrimination: Five lessons for litigators,” SMU Law Review, Vol. 76, forthcoming.

5 Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

6 Robert Sampson, Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

7 More explicitly, we follow borrowers from January 2020 to December 2021 and make four key assumptions to estimate the potential savings: 1) We assume that borrowers refinance when mortgage rates are at their lowest, which occurred in December 2020; 2) following conventions in the literature, we assume a range of 50 to 75 basis points for the up-front cost of refinancing in amortizing that cost; 3) we assume that all borrowers refinance to the same interest rate; and 4) we assume that borrowers obtain a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage when they refinance.