Millions of Americans every year lose what had once seemed stable jobs due to factors including technological change, company or plant closings, alterations in trade patterns, and mass layoffs. Such job displacements have deep impacts on the affected workers, according to multiple studies.

The broader society, too, may pay a significant price. In the U.S., where there are long-term trends of declining intergenerational economic mobility (Aaronson and Mazumder, 2008; Chetty et al., 2017), it seems important to understand more fully the consequences of job displacement, defined as the involuntary loss of employment for reasons other than performance.

While a large literature in economics has documented the sizeable and lasting negative effects of a job displacement on employment outcomes, few have explored its impact by demographic and parental socioeconomic status. In our 2022 report published by the Brookings Institution—and discussed at a 2023 Chicago Fed Economic Mobility Project event—we find not only a large and long-term effect on the earnings of all workers who are displaced, but also that workers who are Black, workers without a bachelor’s degree, and workers whose parents have below-median incomes are more likely to experience a job displacement in any given year.

The unbalanced distribution of job displacement suggests that it may play a significant role in driving inequalities across demographic and socioeconomic groups and in contributing to the decline in economic mobility between generations.

Background

Our research examines job displacements that occurred between 1989 and 2019 among workers ages 25 to 55, and we focus on workers who have worked at least two years full time with their employer before being displaced. This is a group with strong labor-force attachments.

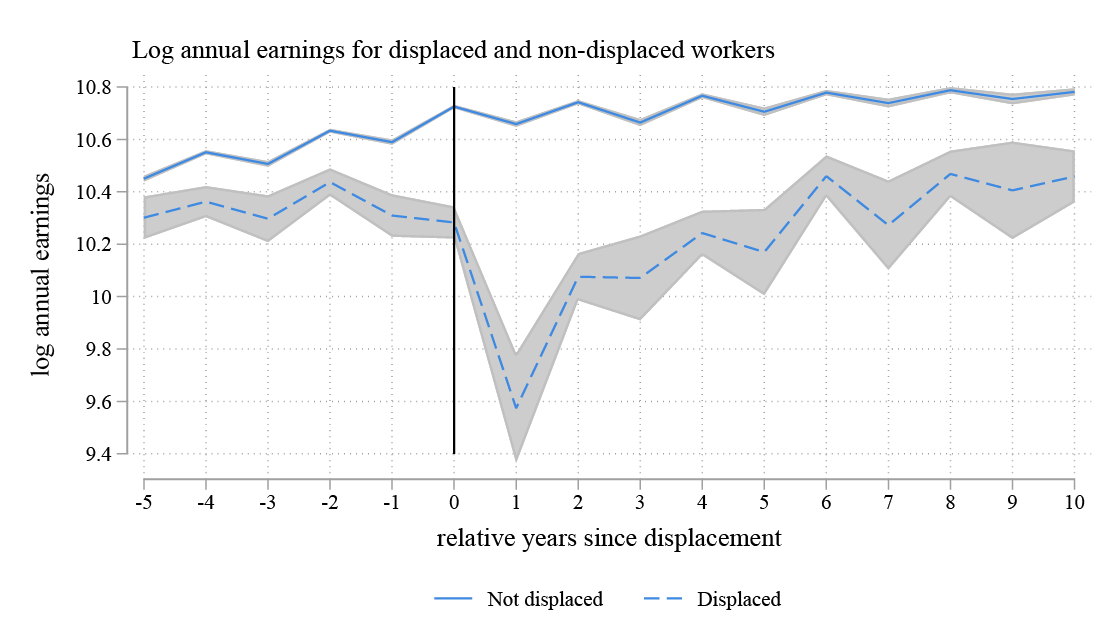

Displacement effects are striking across the board. In the first year after being displaced, workers experience a dramatic drop in earnings (on the order of 60%; see Figure 1) relative to their pre-displacement level. Notably, this impact lingers: Ten years after being displaced, these workers have earnings that are still 25% lower than those of non-displaced workers—and non-displaced workers, by contrast, experience consistent growth in earnings over time. Our analysis shows that the longer-term, lingering effect of a job displacement on annual earnings is driven by displaced workers finding lower-paying jobs after displacement, rather than by working less.

1. Earnings trajectories

Source: Authors' calculations using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

But there is also meaningful variability to be seen in digging deeper into the data, and it starts with the likelihood of displacement. In any given year, Black workers are 67% more likely to experience a job displacement than their White peers. Workers without a bachelor’s degree are also 67% more likely to be displaced than those with a bachelor’s degree. And workers whose parents are in the bottom quintile of the income distribution are 27% more likely to be displaced than those with parents in the top income quintile.

Interestingly, though, while workers with at least a bachelor’s degree initially experience a slightly smaller impact on earnings, the negative effect of job displacement seems to persist longer for them than it does for their peers without a bachelor’s degree. By the tenth year after the displacement event, individuals without a bachelor’s earn 18% less than their non-displaced peers; for workers with a bachelor’s, the number is 36%.

Comparing White and Black displaced workers, we find that the effects of the job loss over time are similar for both race groups, but large differences in earnings levels still exist across all relative years. In the year after a displacement, non-displaced White workers earn roughly $11,500 more than their non-displaced Black peers, on average.

As for the question of parental income, we find strikingly similar effects of displacement on workers with high-income parents and those with low-income parents. This diverges from a pioneering Finnish study (Kaila, Nix, Riukula, 2021) on this question, which found much larger earnings losses in the group with parents in the bottom quintile of income vs. those in the top.

Policy considerations

- Traditional unemployment insurance assumes that what is needed is money to tide a worker over until they get their old job, or one very similar to it, back, but that doesn’t fit the way job displacement plays out. Jobs may be lost due to technology changes, and workers often return to the workforce in very different positions. Meanwhile, the connections and skills they’ve developed specifically relevant to their former employer do not automatically serve them in a new position. Policymakers should consider different approaches to unemployment assistance, including retraining programs, wage insurance, and wage subsidies when switching fields.

- Parental income is important to study because it gets at questions of intergenerational economic mobility. Our research shows similar lasting impact on displaced workers with high- and low-income parents, but the lower-end cohort is much more likely to be displaced in the first place. And those with higher-income parents are likely to have more flexibility in the choices they make on when and where to return to the workforce; they may also have a broader range of connections. If the U.S. wants to begin to reverse the trend of declining economic mobility between generations, further study based on parental income level seems warranted.

- While college education remains a meaningful driver (Barrow and Malamud, 2015) of income growth, disruptions caused by job displacement look to be particularly costly for those with a bachelor’s degree. That said, those with a college degree are less likely to be displaced and more likely to have higher income levels than those without a college degree, so encouraging higher education continues to be sound policy.

- While the number of jobs in the United States has recovered to pre-Covid-recession levels, many of the workers who were displaced in 2020 will likely continue to feel the negative effects of their job displacement for years to come, especially in cases where structural changes mean that old jobs are not returning. Researchers and policymakers alike should work to understand both the negative effects resulting from these displacements and the possible policy solutions that could reduce their impact.

- Finally, amid all the finer points of the discussion, it is important to remember the big takeaway from our and many other studies through the years: Losing a job hurts, immediately and in the long term, and it lowers a worker’s financial prospects over a lifetime. Such findings suggest that policies that reduce labor market disruptions and ameliorate disruptions when they occur can have a profound and lasting impact across all demographic groups, but especially among those more likely to be displaced in the first place.

Kristin F. Butcher is a Chicago Fed vice president and its director of microeconomic research. Ariel Gelrud Shiro is a research associate with the Broad Center at the Yale School of Management at Yale University.