One of the strengths of the American university system is the availability of external financing to enable students of all income and asset levels to obtain a college education. The federally funded student loan system is a key element in the overall funding structure. Undergraduate students from households that demonstrate financial need are granted access to federally subsidized loans that generally offer lower interest rates, deferral of interest charges while in school, and some flexibility in repayment schedules.

Nevertheless, parents and/or guardians might choose to lean on their savings or alternative sources of credit to avoid having their student start their adult life with a potentially sizable financial obligation. Thus, it is important to consider what happens to students when household wealth deteriorates and how that experience affects the students’ long-run well-being.

Researchers Janice Eberly, John Mondragon and I looked at the cohort of students entering college on the heels of the 2007–09 Great Recession to see how the deterioration of the key component of household wealth, namely the reduction in home equity, affected their parents’ ability to support the costs of college. We find that for every dollar of home equity that parents did not draw upon, the student borrowed between 40 and 80 cents to replace it. This analysis shows that the loss of home equity during the Great Recession shifted the responsibility for education expenses to students, setting off longer-term economic effects.

We do not find that this shift in financial responsibility resulted in a change of whether or where to enroll in college, which is a positive for education outcomes. We also find, perhaps intuitively, that parents whose students borrowed more to compensate for the loss of home equity were able to rebuild their non-housing wealth more quickly. However, we also observed that this student cohort worries more about money, is more likely to work during college, and is less likely to own a home or a car after graduation. This cohort is making different investment decisions than have been observed in previous generations, in part due to an increased debt burden—and this warrants additional research.

Background

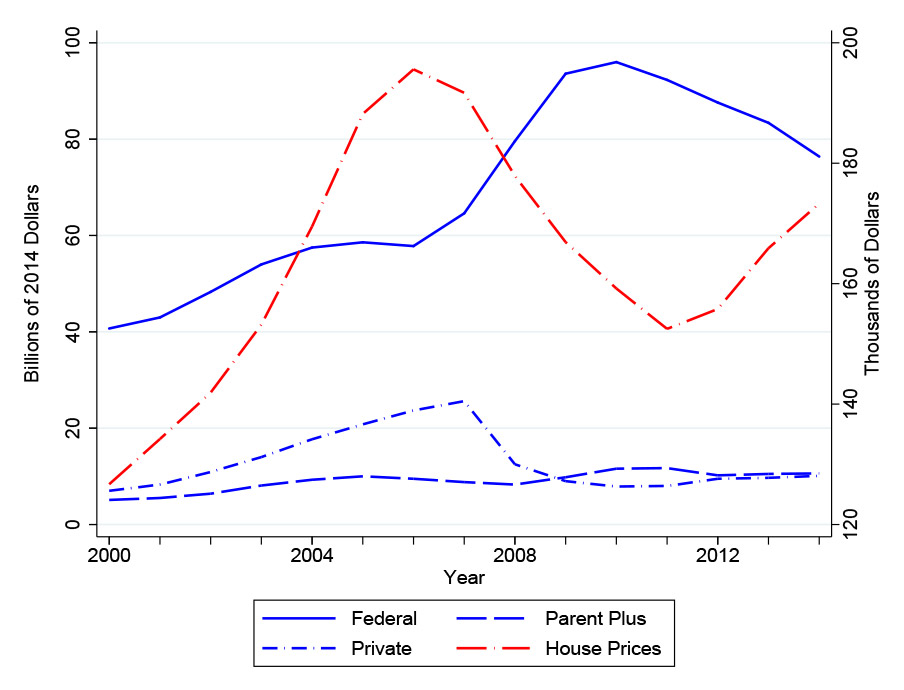

The flow of federal student loans increased 50% between 2007 and 2010 as home prices dropped significantly.

Aggregate Loan Flows and House Prices

Many reasons could explain some of this increase, including higher enrollment and the deterioration of the private student loan market. However, the increased enrollment does not account for the higher balances per student observed, and the private loan market was small overall, so neither factor provides a fully satisfying explanation.

The other popular narrative is that college just became much more expensive during this period, which we do observe in our research in “sticker prices.” However, the implied net cost of public-school tuition only increased by about 2% annually between 2006 and 2015 (the end of the period observed) and was basically flat at private, nonprofit colleges.1 This means that the increased published costs were not reflective of prices paid by students and their households. Further, from the peak in 2010–11, total annual student and parent borrowing was down 33% in 2021–22, supporting the idea that the growing sticker price of college does not explain the loan increases observed post Great Recession.2

The figure above is suggestive of potential links between the erosion in housing wealth and student loan burdens. To study it more closely, we compared borrowing decisions of families enrolling students in college that had experienced housing losses of different magnitudes with those of families that did not have a college-aged student during the Great Recession. To illustrate, one such family may have owned a house in Arizona where home prices plummeted by 40%, while another family resided in Iowa, where prices remained effectively unchanged. In both cases, our analysis takes as the baseline families experiencing similar housing shocks but not having a college-aged student in their household.

Our research confirms that households with higher equity were six times more likely to use it (typically through a cash-out refinancing transaction) when they had an enrolled student. Such higher-equity households also tended to have more wealth outside of home equity and used some of that as well to support the enrolled students.

Students whose families lost housing wealth—lower-equity households—were much more likely to take out a loan, replacing between 40 and 80 cents of each dollar that their equity-constrained parents could not extract from their property. These students were also more likely to work while in college, and they were twice as likely to worry about money. This shift in responsibility for education financing can be observed in parents’ wealth as well. Parents who spent less of their income on education were able to accumulate more non-housing wealth.

This shift has left a lasting imprint. In particular, by the time students from low-equity households reached the age of 30, their higher loan balances were associated with a lower likelihood of owning a house or living independently. Although this question requires additional study, we did not detect parents making lump sum repayments of their student’s outstanding debts once their housing equity recovered. If this proves to be the case, it would imply the shock of the Great Recession and its impact on housing value have facilitated the transfer of education debt burdens from parents to their children.

Policy considerations

There are already negative effects from this increased loan burden—increased worry, less investment in housing—and it is only reasonable to assume that the effects will continue to compound. It is important for us to consider what the increased debt burden might mean for this cohort’s future.

It is useful to look at the student loan burden through a larger, more holistic lens versus the "sticker price" of college. Much of the narrative about increasing college costs may be overshadowing the conversation of how parents and students share in paying for their education and what universities have been doing and can continue to do to support incoming students. Additional study of the net cost of attendance, available household support, and financing options might better inform policy going forward.

And lastly, by highlighting a link between family housing wealth and student borrowing, our analysis suggests that future deterioration in housing values may result in higher indebtedness among the youngest adults, affecting the trajectory of their lifecycle consumption and savings decisions. Policymakers may want to consider ways to lessen the long-term impact on students during times of widespread housing stress; we haven’t analyzed potential solutions but there are many that would be worthy of study, including further consideration of conditional repayment plans and/or the need for additional federal funding for students and universities.

Notes

1 See the College Board’s average net price trends, available online. Reliable figures for for-profit colleges are not available and those may have been higher than the 2% number used here.

2 See the College Board’s average net price trends, available online.