The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

An examination of the global linkages between an expanding world economy and the midwestern United States economy was the focal point of a workshop held at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago on September 18, 1996. The workshop was the sixth in a series held in conjunction with the economic research department’s yearlong project, “Assessing the Midwest Economy.” This Chicago Fed Letter draws on ideas discussed at that workshop, focusing on the Midwest’s role in an increasingly interdependent world market.1

The workshop delved into issues that in recent years have been recognized as increasingly important to the region’s economic well-being and growth. During the past decade, the region’s economy has become increasingly involved in international trade in goods and services, faced a surge in foreign investment in the goods and services sectors and the financial sector, and experienced the impact of political initiatives designed to facilitate or exploit the greater interaction and interdependence of the international economy. These developments have left an indelible mark on the Midwest economy.

Although it is clear that the domestic market remains the dominant influence on the Midwest’s economic condition, the fabric of the Midwest economy has become intricately interwoven with that of the international economy. For continued growth, regional industries now look not only to the domestic market, but also to new or expanding markets abroad. This is especially evident when a slowdown in domestic demand occurs; at such times in recent years, industry observers have anxiously looked to foreign demand to pick up the slack. Moreover, while it has not been an easy transformation, the current strength of Midwest industries owes much to the structural modifications in the economy that were forced, in part, by competition from imports and the competitive nature of foreign-owned entities that have become an integral part of the domestic market.

The economic revival that has occurred in the Midwest during the past decade has important underpinnings in the increasingly worldwide scope of markets. Expanded international trade in goods and services, made easier by the reduction of tariff and nontariff barriers under agreements such as the U.S.–Canada Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), has contributed to Midwest economic growth. At the same time, the region has benefited from rapid economic expansion in emerging markets and continued moderate to strong demand from developed markets around the world.

Arguably the most important development contributing to the Midwest’s economic revival has been the critical restructuring of its industrial base during the past ten to 15 years. Industrial restructuring has enhanced Midwest (and U.S.) industrial competitiveness in world markets, i.e., foreign and domestic markets (this characterization of the market is important to understanding the progress made by industry in its drive toward international competitiveness). The world market can no longer be thought of as the foreign market only; for an industry to be competitive in foreign markets, it must also be competitive in the domestic market. The provincial view that these two markets are separate, at least for tradable goods and services, is no longer appropriate.

Midwest industries’ improved competitiveness in world markets owes much to the competitive impact of imports from abroad, technology transfers and competition from foreign direct investment in major Midwest industries, and increased interregional competition within U.S. borders.

International trade— a national activity

Although we may think of an industry’s market as worldwide, national borders still define whether a trade or investment activity is international or domestic. Within the U.S., international agreements and, therefore, the degree of openness of borders, are within the purview of the federal government. Since the late 1940s, the U.S. has participated in numerous trade agreements that have dramatically reduced tariffs and opened national borders to international trade. The trend has accelerated in recent years. The U.S.–Canada Automotive Products Agreement was negotiated in 1965, the U.S.–Canada FTA in 1989, and NAFTA in 1994. Even more important were the eight post-World War II multilateral trade agreements, the first round of which established the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. The most recent of these agreements, the Uruguay Round, replaced GATT with the World Trade Organization in 1995.

National policies also influence the rate of domestic inflation, the exchange rate of the dollar relative to other currencies, codes affecting interstate movement of goods, national tax codes, financial market regulations, agricultural production decisions, and environmental, safety, and health regulations. While such national policy actions may be aimed at the domestic economy, they inevitably affect the interaction between the domestic economy and the international economy. The more open the national borders are to trade in goods and services and financial flows, the more impact these non-trade-specific national policies will have on an economy’s international involvement.

National policy actions, whether related to international trade or aimed primarily toward influencing the domestic economy, can also be expected to have different effects on the various regions of the United States. The Midwest economy has responded well to the relaxation of international trade barriers in recent years, though not without difficult and extensive industrial restructuring. The recovery of the Midwest economy from its Rust Belt reputation of the 1970s and early 1980s and its recent success in export markets are due importantly to the composition of the region’s industrial mix, which is heavily oriented toward the manufacturing of capital goods and automotive equipment, and agricultural production and food processing. The appreciation of the dollar exchange rate during the early 1980s and the negotiation of lower trade barriers through the various GATT rounds during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s encouraged a rapid influx of imports, which led to increased competition for domestic industries.

Midwest industries, especially those that were international in scope, responded to this increased competition with a comparatively successful restructuring. Foreign direct investment in new facilities, as well as existing U.S. firms, was an important factor contributing to the growth and retention of some midwestern industries, for example, electrical machinery (see figure 1). Foreign investment in industries that are important to Midwest manufacturing recorded substantial growth, as reflected by employment growth, during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Figure 1 reports rapid employment growth in foreign affiliates associated with electrical and industrial machinery, instruments, transportation equipment, primary and fabricated metals, and the like, relative to employment growth for all U.S. businesses in those categories. In addition, foreign financial institutions entered the region’s banking market and provided new sources of competitively priced funds.

| Selected industries | Foreign affiliates | All U.S. businesses | ||

| Employees | Growth | Employees | Growth | |

| (thousands) | (percent) | (thousands) | (percent) | |

| Total manufacturing | 2,004.6 | 52.9 | 18,061.7 | –4.7 |

| Food and kindred products | 156.7 | 42.3 | 1,467.2 | 2.9 |

| Furniture and fixtures | 10.0 | –35.1 | 421.8 | 14.7 |

| Paper and allied products | 49.5 | 14.5 | 587.9 | 3.0 |

| Printing and publishing | 100.6 | 94.3 | 1,465.6 | 2.8 |

| Chemicals | 232.6 | 35.4 | 842.1 | 4.5 |

| Rubber and misc. plastics | 118.3 | 84.3 | 822.0 | 3.6 |

| Primary metals | 120.7 | 54.5 | 651.8 | –1.0 |

| Fabricated metals | 101.8 | 65.6 | 1,350.5 | –4.1 |

| Industrial machinery | 192.7 | 66.1 | 1,766.5 | –2.2 |

| Electrical machinery | 235.5 | 38.2 | 1,423.8 | –7.9 |

| Transportation equipment | 106.9 | 91.6 | 1,488.1 | –5.6 |

| Measuring instruments, photo goods, watches | 112.7 | 54.7 | 877.7 | –5.0 |

The automotive industry, heavily concentrated in the Midwest, was profoundly influenced by developments in the international sector. The 1965 U.S.–Canada Auto Pact promoted harmonization of the industry and the development of a single market across the national border. The industry then had to adjust to growing international competition in the domestic market, initially from imports and more recently from the transplanting of foreign production (that is, foreign investment) to U.S. locations, in many cases the Midwest. To the domestic auto industry’s credit, it has been able to adjust to meet this competition. Its challenge will be to continue to meet that competition.

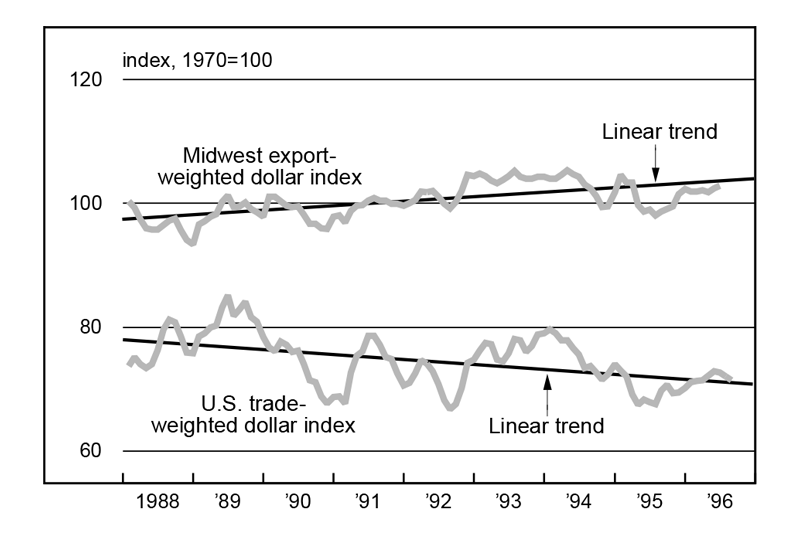

Midwest industrial restructuring contributed importantly to rapid growth in shipments to foreign markets during the late 1980s and early 1990s. This development occurred despite the fact that the primary markets to which Midwest industry exports (North America) faced a dollar exchange rate that was appreciating (not depreciating as is typically thought to be the case), as can be seen in figure 2.2

2. Dollar facing Midwest exporters appreciates

Agricultural exports, primary products and processed foods, have also surged in recent years. The Midwest is the heart of U.S. feed grain and oil seed production; it is also an important center for the food processing industry.

Much of the expansion in U.S. exports has occurred in response to growth in emerging markets. Indeed, some estimates suggest that nearly three-quarters of future growth in world trade will arise from such markets. Demand for capital goods—machinery and equipment—is particularly high in emerging markets and the Midwest is well positioned to respond in this area. Recent evidence of NAFTA’s impact on market expansion to Mexico suggests that Midwest gains have accrued through an expansion in durable goods manufacturing activity.

Open borders to direct investments have assisted the Midwest in several ways, including the adoption of world-class technologies and modes of business operation. In some cases, technology transfer has occurred through information/communication channels as multinational and midwestern companies that sell worldwide have adopted new standards and processes. In other cases, foreign domiciled firms—both manufacturers and service firms—have relocated operational skills directly to the Midwest. Joint ventures between domestic and foreign firms have also helped domestic firms to invest in cutting edge technologies (e.g., integrated steel mills). Open borders at the national level have made this transformation possible; regional amenities and infrastructure may also have contributed.

The role of state and metropolitan governments

As individual nations become more interdependent with the rest of the world through the reduction of trade and investment barriers, national governments cede some of their economic and, hence, political authority to multinational bodies. Some observers suggest that, as a result, the economic role of subnational political jurisdictions, such as states and metropolitan areas, is likely to grow. Indeed, states and metro areas in the Midwest have moved toward becoming hosts and centers for foreign investment and the export of services worldwide— business services, financial services, business travel, and tourism. However, the current model of participating in the expanding international marketplace by states and metro areas is that of interstate or intercity competition. Some observers suggest that the European model of intercity cooperation to promote cities’ relative advantages would be a more productive approach and would in turn help U.S. cities attract global investment.

There is much more to be understood about the pattern of interregional linkages (local, regional, and international), how they are evolving, and how they are interacting. Many questions remain unanswered about what makes these linkages work and what sort of impediments inhibit their efficient operation. Useful answers to any such questions require the formulation of meaningful and appropriate questions. In this spirit, some reasonable questions that might be addressed include: Are there significant unmeasured interstate and international flows in services as well as manufactured goods? What are the implications of policies that promote distortionary regulations, taxes, and other fiscal issues that may be limiting intraregional, interregional, and international trade, investment, and labor flows—policies such as different weight and length limits on trucks; different state and local tax regimes; barriers and impediments to skilled labor migration; prohibitions against foreign ownership of property; and trade distortions among states or across international borders, arising from selective tax policy or restrictions on imports that grow out of purposefully distortive, as well as legitimate, health, safety, and environmental regulations? Conflict over such issues is inherent in the interplay of economic and political forces.

Clearly, international as well as intranational economic linkages are complex, and becoming more so. The papers and discussions presented at the Chicago Fed’s global linkages workshop shed some light on these issues. Nonetheless, what most clearly emerged from this endeavor was another pattern. While the search for understanding often answers some questions and may provide some insightful guidance for policy, it also raises more questions. A willingness on the part of researchers and policymakers to risk asking difficult (and potentially unpopular) but relevant questions, answering those questions as best they can, and then engaging in good faith dialogue to try and find a way of implementing the results holds the potential of contributing positively to the future prosperity of the Midwest economy.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1992=100)

| January | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFMMI | 124.3 | 124.4 | 118.2 |

| IP | 119.1 | 119.4 | 113.4 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| January | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cars | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.7 |

| Light trucks | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.3 |

Purchasing managers' surveys: net % reporting production growth

| February | Month ago | Year ago | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 60.1 | 60.8 | 55.8 |

| U.S. | 59.3 | 58.0 | 46.2 |

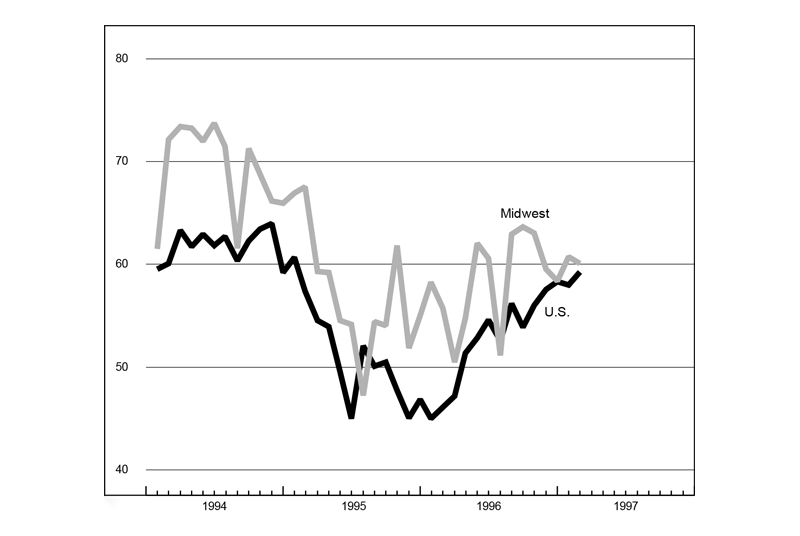

Purchasing managers’ surveys (production index)

Midwest manufacturing activity remained expansionary in February, although the production component of the composite purchasing managers’ index edged down from 60.8 in January to 60.1. This pace has been in line with the nation. The national production component was only slightly below the region at 59.3, although the nation recorded a slight pickup from the previous month.

Among other contributors to strength, the supplier deliveries component of the Chicago purchasing managers’ index jumped from 47.6 (consistent with a shortening of delivery time) to 56.0 (consistent with a marked lengthening of the amount of time it takes to make deliveries). If sustained in other metro areas, price increases could begin to accelerate. So far, most indications are that labor and material costs have remained tightly constrained.

Notes

1 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Global Linkages to the Midwest Economy, Number 6 in the Assessing the Midwest Economy summary series, September 18, 1996. Summary publications for the other five workshops are available from the Bank’s Public Information Center—Number 1, Midwestern Metropolitan Areas: Performance and Policy; Number 2, The Midwest Economy: Structure and Performance; Number 3, The Changing Rural Economy of the Midwest; Number 4, Work Force Developments: Issues for the Midwest Economy; and Number 5, Designing State–Local Fiscal Policy for Growth and Development.

2 Jack L. Hervey and William A. Strauss, “A regional export-weighted dollar: A different way of looking at exchange rate changes,” Assessing the Midwest Economy Working Paper Series, No. GL-2, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1996.