The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

In recent years, the use of antidumping duties has been growing around the world. What caused the explosion in the use of a once-obscure trade remedy?

Beginning in 1980, the use of antidumping duties—special import tariffs that are used to raise the price of “dumped” goods—came to be a common practice in conducting trade policy among the U.S., the European Union (EU), Canada, and Australia. While only a handful of antidumping cases were initiated worldwide in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, more than 1,600 cases were filed during the 1980s. Of these, the vast majority were filed by the traditional users—the U.S., the EU, Canada, and Australia. However, prior to the advent of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, the use of antidumping protection began to spread to developing countries, most notably India, Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa.

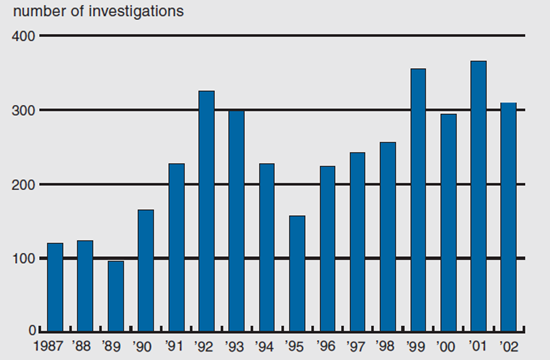

The worldwide explosion in the use of antidumping duties has been widely documented (see figure 1; also Prusa and Blonigen, 2003; Miranda, Torres, and Ruiz, 1998; and Messerlin, 1989, among others).1 Over the five-year period from 1987 to 1991, 733 antidumping investigations were conducted worldwide. Between 1992 and 1997, the number increased to 1,463. Most recently, between 1998 and 2002, 1,581 antidumping investigations were filed.

1. Worldwide AD investigations: 1987–2002

What caused this explosion in the use of a once-obscure trade remedy? Why are countries increasingly trying to restrict their imports through the use of antidumping duties, while at the same time engaging in broad programs of trade liberalization? What effect does this shift in trade policy have on consumers and producers both here and abroad? This Chicago Fed Letter reviews some of the newer explanations that have been offered to explain the antidumping phenomenon. Changes in international trade laws, probably the most important factor in the rise of antidumping protection, fostered an environment in which many countries increased their use of antidumping protection without any specific regard for the trade policies of their trading partners. More recent research, which I discuss here, examines if there are linkages across countries in the increased use of antidumping duties.

Put simply, for countries that belong to the WTO, dumping is selling an exported product in a foreign market at a price that is lower than the product’s price in its home market, a third market, or below its average cost of production.2 Dumping is often called unfair because many confuse its definition with the economically harmful practice of predatory pricing. Although dumping is not necessarily harmful and, in fact, benefits consumers through lower prices in most cases, the WTO allows the use of antidumping duties to raise the price of dumped products. Under WTO rules, an importing country can impose an antidumping duty if there is proof that dumping is occurring and that it is causing injury to the domestic firms that compete with the dumped goods.

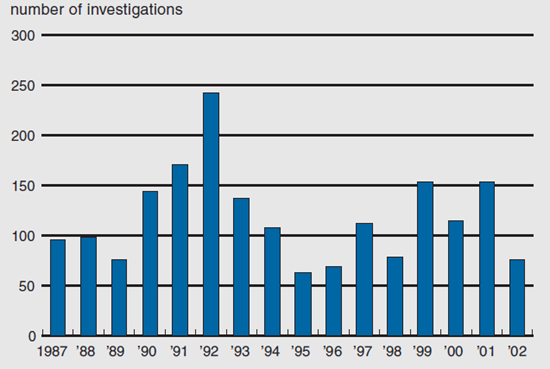

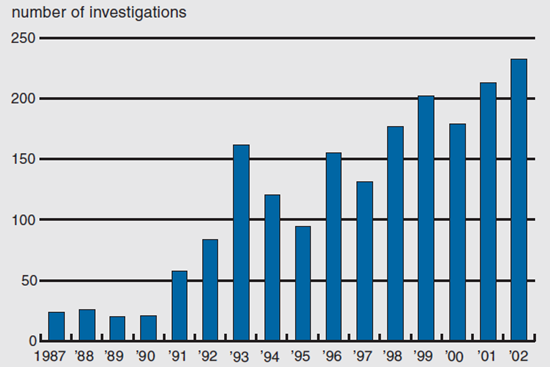

Figure 2 presents the total number of antidumping investigations by the U.S., EU, Canada, and Australia over the last 15 years. Among traditional users, the number of antidumping investigations fluctuates considerably from year to year with no clear trend over time. However, in figure 3, which plots the total number of antidumping investigations by all other GATT–WTO members, we see that there has been a steady increase in the number of antidumping investigations over this period.

2. AD investigations by traditional users: 1987–2002

3. AD investigations by new users: 1987–2002

There are many potential explanations for the rise in antidumping protection and I discuss only a few. Ultimately, the rise of antidumping protection can be traced back to changes in the rules-based trading regime of the WTO and its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The first major increase in the use of antidumping duties began after rule changes introduced during the Tokyo Round of trade negotiations in 1979. The first surge in the use of antidumping duties was concentrated among the U.S., EU, Canada, and Australia, all GATT members. The second major increase began in the early 1990s as numerous developing countries joined the GATT and, later, the WTO. In signing on to the rules-based trading regime, countries agreed to restrict their use of import tariffs and other barriers to trade. It appears that in some cases, facing competitive pressure from lower-priced imports, countries whose firms compete with imports turned to one of the few loopholes in the WTO rules, the use of antidumping duties.

In addition to this important explanation, linkages among countries may have affected the frequency of antidumping activity. As the use of antidumping duties has spread, researchers have begun to examine if the use of these policies in different countries is linked, either directly through the strategic behavior of governments or indirectly through the use of antidumping policies to control import surges caused by other countries’ antidumping duties.

One factor behind the rise of antidumping protection could be that countries are engaging in retaliatory mini-trade wars. If one country imposes an antidumping duty against another, the second country will retaliate by imposing its own antidumping duty against the first. A 2002 paper by Tom Prusa and Susan Skeath3 examines whether the increasing use of antidumping duties is due to economic factors, like a rise in dumping, or strategic factors, like retaliation. They study antidumping cases filed by GATT–WTO members between 1980 and 1988 and find evidence for a strategic motive in the initiation of antidumping cases. Specifically, they find that a country is more likely to begin an antidumping case against its trading partner if the trading partner used an antidumping duty against it in the past. Prusa and Skeath argue that their results “help to reject the notion that the rise in antidumping activity can be solely explained by an increase in unfair trade.”

While Prusa and Skeath find a significant retaliatory motive behind the proliferation of antidumping duties, a study by Blonigen and Bown (2003)4 suggests that the threat of a retaliatory antidumping duty could eventually have a “cold war” effect that dampens antidumping activity if antidumping laws become more widespread. They argue that a country that is contemplating an antidumping duty against an important trading partner may actually refrain from imposing the measure if there is a threat of retaliation. In their examination of U.S. antidumping activity from 1980 to 1998, Blonigen and Bown find that if a country is a significant export market for U.S. producers, and thus has the ability to adversely affect U.S. exporters through its own retaliatory antidumping duty, the U.S. is less likely to impose an antidumping duty in the first place. An interesting implication of this is that such a cold war effect may not materialize and instead the use of antidumping protection may be biased against small and developing countries if such countries continue to have little ability to retaliate effectively against an antidumping duty imposed by a major trading partner.

Taken together, what do these two papers tell us about the role of retaliation in the spread of antidumping protection? It may be that credible threats of retaliation can lead to a dampening of antidumping activity, but that noneconomic, strategic motives are an important factor in the rise of antidumping protection.

A 2003 paper by Bown and Crowley5 postulates that some of the increase in the use of antidumping duties may be related to the problem of trade deflection. Bown and Crowley examine what happens to the exports of a country, specifically Japan, when it faces U.S. antidumping duties. Using highly detailed data on flows of Japanese exports to almost all the countries in the world, Bown and Crowley try to determine if the imposition of U.S. antidumping duties on Japanese products leads to an increase in Japanese exports to other countries, i.e., trade deflection. After controlling for a variety of other factors, like changes in gross domestic product growth, industry productivity, and movements in the exchange rate, Bown and Crowley find that Japanese export growth to countries other than the U.S. increases by roughly 10 to 20 percentage points when the U.S. imposes an antidumping duty on Japanese products.

Figure 4 illustrates Bown and Crowley’s main finding of trade deflection. This figure graphs the average growth rates of Japanese commodity exports by their destination—the U.S., the EU, and non-EU third countries—if the exports were subject to a new U.S. antidumping duty between 1992 and 2001. It plots the average growth rates of Japanese exports in the year in which the antidumping case was initiated (time t) and in the two years prior to the initiation of the antidumping investigation.6 The blue line designates exports to the U.S. that are subject to a new U.S. antidumping duty. As one might expect, in the year before a successful antidumping case is initiated, growth of the products that eventually face an antidumping duty is very high, slightly below 30%. In the year in which an antidumping case is initiated in the U.S., the growth of Japanese exports falls to –10%. By way of comparison, the average growth rate of all commodities exported from Japan to the U.S. between 1992 and 2001 was roughly 0%.

More interestingly, the black line plots the average growth of Japanese exports to the EU in the year in which a successful U.S. antidumping investigation begins and in the two years prior. Although there is little change in the growth of these Japanese commodity exports to the EU in the two years prior to the U.S. antidumping investigation, in the year in which a U.S. antidumping investigation is initiated, Japanese exports to the EU surge to over 25%. Bown and Crowley interpret this as “trade deflection.” They hypothesize that the commodities that the Japanese had planned to sell in the U.S. market are redirected to the EU in response to the adverse change in U.S. trade policy.

We see a similar pattern of trade deflection in Japanese exports to other, non-EU countries. While export growth of the specific commodities is close to zero in the periods before the initiation of a U.S. antidumping duty, it jumps up to about 3.5% when the U.S. initiates a successful antidumping investigation. The EU may be a preferred destination for deflected trade because it is a large market with demand for many of the same goods that Japanese firms sell in the U.S. and because many Japanese firms have a presence in the EU, making it relatively easy to shift sales there.

How does this finding of trade deflection relate back to the question of the explosion in the worldwide use of antidumping duties? Bown and Crowley speculate that trade deflection may be one of the pathways through which antidumping duties are multiplying. For example, if a U.S. antidumping duty against Japan leads to a surge of Japanese imports into the EU, the EU may then respond with its own antidumping duty against Japanese exports. The EU antidumping duty may then induce further trade deflection and antidumping duties in other countries. As Japanese exports chase the remaining open markets, antidumping duties rise.

Conclusion

This Chicago Fed Letter has summarized some of the explanations for the dramatic increase in the use of antidumping protection over the last 20 years. In addition to changes in international trade laws, linkages across countries may also have affected the use of antidumping protection. The idea that trade deflection could be behind the increased use of antidumping duties is especially troubling, because it suggests that worldwide trade in some products may collapse to highly inefficient levels as more and more countries turn to antidumping protection in the face of deflected import surges. Further research utilizing data on the timing of antidumping investigations for specific products on a worldwide basis could help to clarify whether trade deflection or retaliation is behind the spread of this newly important form of protectionism.

Notes

1 Thomas J. Prusa and Bruce Blonigen, 2003, “Antidumping,” in Handbook of International Trade, E. Kwan Choi and James Harrigan (eds.), Oxford, UK, and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers; Jorge Miranda, Raul A. Torres, and Mario Ruiz, 1998, “The international use of antidumping: 1987–1999,” Journal of World Trade, Vol. 32, pp. 5–71; and Patrick A. Messerlin, 1989, “The EC antidumping regulations: A first economic appraisal, 1980–85,” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, Vol. 125, pp. 563–587.

2 See M. Crowley, 2003, “An introduction to the WTO and GATT,” Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Fourth Quarter, pp. 42–57.

3 Thomas J. Prusa and Susan Skeath, 2002, “The economic and strategic motives for antidumping filings,” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, Vol. 138, pp. 389–413.

4 Bruce Blonigen and Chad Bown, 2003. “Antidumping and retaliation threats,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 60, pp. 249–273.

5 Chad Bown and Meredith Crowley, 2003, “Trade deflection and trade depression,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, mimeo.

6 In most cases, antidumping cases are initiated and duties are imposed in the same year. In some cases, duties are imposed in the following year.