This article examines the potential aggregate impact on financial stability of several bilateral force majeure claims filed at approximately the same time in one or more markets. One and a half years after the pandemic started, I take stock of the developments involving force majeure claims thus far, and conclude that the likelihood of these claims creating a systemic threat to financial stability is low.1

Many financial and commercial contracts contain a provision stating that the performance of the contract can be excused or delayed on the basis of force majeure. Force majeure is an event that makes it impossible or extremely difficult for a party to perform its obligations under a contract. The event must be the cause of nonperformance or delay in performance under the contract; also, the event must be more than an inconvenience, a loss of profit, or an increase in the cost of performing. The exact characteristic of a force majeure provision differs from contract to contract; in some cases, an event must be unforeseeable for it to qualify as force majeure.2

Force majeure issues came to the fore during the spring of 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded in the U.S. and other jurisdictions. Force majeure claims initially emerged within the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets in March 2020, after a period of extreme volatility in interest rates. Force majeure was also declared in the oil markets, after West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil traded at close to negative $40 per barrel on April 20, 2020. Another prominent example occurred nearly a year later—in February 2021, when facing extreme winter weather in Texas, oil producers and chemical companies declared force majeure on their sales contracts.

Overall, U.S. economic and financial conditions have improved since the spring of 2020. But some of the underlying effects of the Covid-19 crisis remain in various markets—and there’s still much uncertainty surrounding the potential impacts of the Covid-19 variants. Texas has recovered from the extreme-weather-related power crisis earlier this year. But that event’s longer-term effects on the Texas energy markets are unclear without an in-depth study, which is beyond the scope of this article. Given the private, bilateral nature of force majeure claims, it may take a while until such claims filed in 2020 and 2021 become public knowledge, through either a court filing, a regulatory filing, or press reports.

In this Chicago Fed Letter, I explore the potential impact of force majeure in the markets for commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), residential mortgage-backed securities (MBS), energy, cleared derivatives (particularly futures), and uncleared bilateral OTC (over-the-counter) derivatives. I also account for the potential reach of force majeure claims into an even broader range of markets by briefly discussing “force majeure certificates” issued in 2020 by a quasi-governmental authority in China and by chambers of commerce in Italy.

Commercial mortgage-backed securities

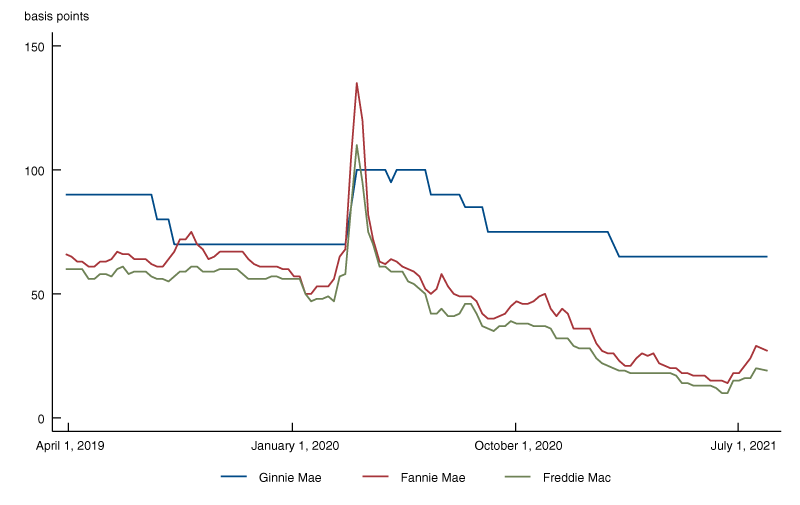

In late March 2020, commercial real estate in the U.S. experienced a significant negative impact as a result of the Covid-19 lockdowns. The retail and hospitality sectors bore the brunt of that impact. Agency CMBS spreads widened at that time, but have narrowed since then (see figure 1). That said, concerns about the impact of further waves of Covid-19 infections and lockdown measures remain. It is worth noting that in the spring of 2020, as part of a package of emergency measures aimed at stabilizing the U.S. economy, the Federal Reserve put in place a CMBS purchase program that may have contributed to the reduction in such spreads.

1. Agency CMBS spreads

Source: J.P. Morgan Research.

Commercial leases in some cases contain force majeure clauses, but often clarify that rent is still payable notwithstanding the occurrence of a force majeure event. Nevertheless, during the Covid-19 lockdowns in the U.S., commercial tenants may have missed payments because they were unable to operate or experienced significant losses. Moreover, eviction moratoriums imposed by the CARES Act and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) could have further increased the likelihood of missed rent payments. As a result of the reduced rent cash flow, landlord borrowers may have been forced to miss mortgage payments or ask lenders for forbearance. Additionally, another CARES Act provision granted borrowers of federally backed mortgages on multifamily properties (such as apartment complexes) a 90-day forbearance period. A collateral effect of this provision may have been that the number of commercial borrowers asking for forbearance rose—which may have in turn increased the liquidity stress on mortgage servicers.

Mortgage servicers are responsible for paying lenders regardless of whether they receive payments from borrowers. If servicers are unable to make their payments, the CMBS market could be negatively affected. In such a scenario, borrowers and servicers may cite force majeure as the basis for their inability to pay. Force majeure claims may cause additional stress if they take years to resolve in the courts or they spill over into the insurance sector.

Residential mortgage-backed securities

In March 2020, some mortgage originators were reported as claiming force majeure; they cited the mortgage forbearance provisions in the CARES Act as justification for missing or threatening to miss margin calls on forward TBA (to be announced) MBS contracts.3 As mentioned before, March 2020 was preceded by a period of extreme interest rate volatility. At that time the value of forward TBA MBS contracts rose sharply, which led to dealers making substantial margin calls to mortgage servicers. These margin calls put liquidity pressures on originators.

Mortgage originators sell TBA MBS contracts to hedge against the risk of rates rising relative to rate locks offered to prospective borrowers prior to loan origination. When rates decline quickly, or when MBS spreads tighten substantially, the value of such short positions declines, prompting margin calls. Most mortgage originators also act as mortgage servicers. Mortgage servicers are responsible for advancing forborne payments to investors for securitized mortgages backed by the two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Pursuant to the CARES Act, all homeowners with federally backed mortgages can receive forbearance for up to 18 months if they claim to experience financial hardship because of the coronavirus crisis. The force majeure argument advanced by servicers in this case is based on the CARES Act forbearance provisions, which have resulted in reduced cash flows from borrowers to servicers.

Because mortgage originators also service the loans they originate, the very entities facing margin calls on their TBA MBS hedges in their capacity as originators are the same ones required to advance the forborne payments in their capacity as servicers. During interviews with market participants conducted by the Chicago Fed, a concern emerged that widespread refusal to meet margin calls could pose a significant risk to the MBS market if dealers were to pull back from it. This could lead to further erosion in the ability of thinly capitalized mortgage originators/servicers to hedge their exposure to interest rate movements and impair mortgage origination flows.

While the CARES Act provided for forbearance for up to 18 months, many nonbank servicers did not have the capital or liquidity to advance 18 months of missed payments, which meant these entities faced additional liquidity pressures. While liquidity pressures resulting from forbearance did not constitute force majeure per se, they constituted an incentive for nonbank servicers to claim force majeure on the collateral calls in their TBA MBS contracts. For agency MBS, the pressures on servicers were eased by Ginnie Mae’s April 10, 2020, announcement of a Pass-Through Assistance Program (PTAP), which allowed servicers of FHA loans to ask Ginnie Mae to advance any forborne payments that they were unable to make themselves. This was followed on April 21, 2020, by the announcement that servicers of mortgages originated by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would only be required to advance four months’ worth of payments for loans in forbearance. In addition, since the issue of TBA MBS margin calls emerged, interest rate volatility has gone down and MBS prices have stabilized. These developments have lessened the pressures in the TBA MBS market.

In March 2020, the Mortgage Bankers Association started tracking the overall percentage of loans in forbearance in the U.S. with its Forbearance and Call Volume Survey. This percentage grew from 0.25% of servicers’ portfolio volume on March 2, 2020, to 2.66% on April 1, 2020. As a result of the Covid-19 crisis, the number of loans in forbearance reached 8.55% as of June 7, 2020, and then gradually decreased to 3.91% as of June 20, 2021, showing continued pressure on mortgage servicers.

Energy and futures markets

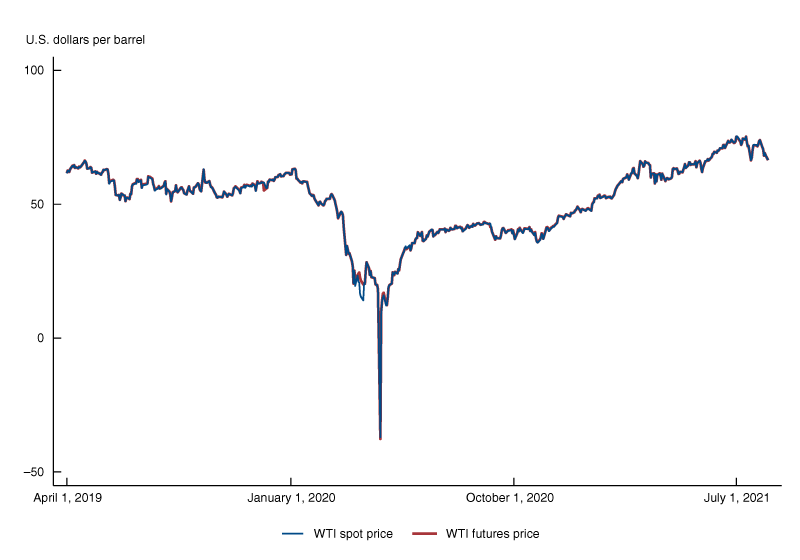

In April 2020, the oil markets experienced extreme stress as Covid-19 lockdowns in the U.S. and elsewhere markedly reduced the demand for oil. As shown in figure 2, on April 20, 2020, NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange) WTI crude oil futures for May 2020 delivery traded close to negative $40 a barrel; WTI spot prices also fell to the same level. The price per barrel of WTI crude oil is one of the leading benchmarks for global oil prices, and WTI crude oil is the underlying commodity for the NYMEX futures oil contract.

2. Spot versus futures prices for WTI crude oil

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration.

How can oil prices go negative? Why would a buyer expect to be paid to take delivery of oil from a seller? The NYMEX WTI crude oil futures contract is physically settled, but a number of market participants do not expect to ever receive physical delivery (i.e., they assume they will sell their futures contracts before the delivery date). When the oil storage center in Cushing, Oklahoma, was close to its maximum capacity in April 2020, the cost of receiving oil pushed the prices for nearby-month WTI oil futures contracts into negative territory. One commentator asked whether only those who can guarantee the ability to receive physical delivery of oil should be allowed to trade oil futures contracts.

In the case of futures contracts, NYMEX and other exchanges have very broad powers to suspend or halt trading in an emergency4 or if an operational or logistical issue arises that affects the ability to deliver the underlying commodity (in this case, oil). The CME (Chicago Mercantile Exchange) Group—NYMEX’s parent company—and the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) operate exchanges and clearinghouses where listed derivatives, including energy derivatives, are traded and cleared. When the CME Group has declared force majeure in the case of physically settled futures (e.g., corn and soybeans), it has directed physical delivery to a depository different from the one in the standard contracts or it has ordered a delay in physical delivery until the issue giving rise to force majeure (e.g., flooding) is resolved. With respect to physical delivery, ICE rules for sugar contracts excuse a delay by the party due to make or receive delivery when delivery is impossible because of force majeure. The CME Group did not declare force majeure on NYMEX WTI crude oil futures during the Covid-19 crisis. Large-scale declarations of force majeure in the futures markets are uncommon and tend to occur when a natural event makes delivery impossible, rather than expensive or very difficult.

In the context of bilateral oil contracts, some producers and importers of oil have claimed force majeure as a reason to cancel delivery. In the spring of 2020, for instance, U.S.-based oil producer Continental Resources Inc. claimed force majeure as a reason to stop delivery of oil to refiners, and the trading arm of Mexican petrol company Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos) claimed force majeure to stop delivery of oil from the U.S.5 As these oil contracts were bilateral (i.e., not traded or executed on an exchange), there was no exchange authority or rulebook to appeal to in cases of force majeure. I discuss force majeure and other types of off-exchange contracts in more detail next.

Uncleared bilateral OTC derivatives

Derivative contracts derive their value from a reference asset or rate—such as a stock (equity derivatives), a commodity (commodity derivatives), the debt issued by a company (credit derivatives), an interest rate (interest rate derivatives), or the exchange rate between two currencies (foreign exchange derivatives). Some derivatives are listed or traded on an exchange—such as the CME, Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), ICE, and Eurex; and others are traded off exchange. Derivatives traded off exchange are often referred to as “over the counter,” or OTC. Let’s take an equity total return swap as an example. In an equity total return swap, party A pays party B if the value of the stock goes up, and party B pays party A if the value of the stock goes down. Let’s say the payment date on which these calculations are made is the 15th of each month. If the stock is listed on an exchange, the parties will need to know that stock’s price on the exchange in order to calculate the amounts due under the swap. In this case the stock is the reference asset. If the exchange is closed, the parties will need to find an alternative price source, also referred to as a fallback, or they may be unable to calculate amounts due under the contract. That inability to identify a fallback may constitute force majeure.

Standard trading terms for uncleared bilateral OTC derivatives, which are set out in the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) Master Agreement and ISDA Definitions, provide fallbacks in case the original reference value becomes unavailable because of force majeure or otherwise. In this context, a force majeure claim would only be available after the parties have exhausted all other fallbacks. ISDA keeps track of disruptions due to Covid-19. To keep running during the Covid-19 crisis, most price sources transferred all their pits trading and in-person operations to electronic platforms in the spring of 2020; some even reopened their open-outcry trading floors with modifications for health and safety by the summer of last year.6

Even if a force majeure event arises, the parties to OTC derivatives trades are not excused from their contractual obligations, but rather, all transactions between the parties are terminated and a single closeout net amount is calculated. A closeout crystallizes positions between the parties: The value of each transaction is calculated and forms part of the overall liquidation value of a portfolio composed of all existing transactions between the parties. This may result in a net payment due to the party invoking the force majeure; but depending on the overall net value of all positions being terminated, this exercise may also result in a net payment due by the party invoking force majeure to the other party. Market participants that wish to continue having derivative positions in place to hedge other exposures or to match their view of future market moves would need to reestablish those positions with potential operational and bid–offer costs (if the market has moved since the calculation of the closeout values).

The clearing mandate was introduced globally for most liquid OTC derivatives as a result of the financial crisis of 2008–09. But also, following that crisis, international regulators developed a framework for applying margin requirements to derivatives that are not cleared. These rules, which are referred to as uncleared margin rules (UMR), include a requirement to collateralize derivative exposure (both variation margin and initial margin) for uncleared derivatives for a large number of market participants.7 This UMR requirement has been gradually phased in since 2016, and thousands of additional end-users were scheduled to become subject to it in September 2020; but on account of the Covid-19 pandemic, they were given another year before they had to be in compliance.8 It remains to be seen whether the delayed implementation of the UMR requirement for some end-users exacerbates the potential negative systemic impact of large closeouts (or a large number of smaller ones) in the uncleared derivatives market.

Given the impact of a closeout on the position of each party, closing out of positions because of a force majeure event is truly an option of last resort. While there have been many publications on the legal aspects of this topic during 2020, to date I am not aware of material force majeure issues in the OTC derivatives market due to the Covid-19 crisis.

Force majeure certificates

Force majeure can affect any financial or commercial contract. Authorities in China and Italy—jurisdictions impacted dramatically during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in early 2020—provided for the issuance of “force majeure certificates” to support local businesses affected by lockdowns. Under Chinese law, the party claiming force majeure is required to provide evidence. The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, a quasi-governmental body, is reported to have issued 7,004 force majeure certificates for contracts worth in aggregate of nearly $97 billion as of April 20, 2020. These certificates are intended to protect Chinese manufacturers, which experienced production delays due to Covid-19, against claims by foreign purchasers. Manufacturers receiving these certificates include steel producers, electronics companies, and auto parts suppliers. As reported last year, in March 2020, the Italian Ministry of Economic Development (Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, or MISE) issued a circular directing Italian chambers of commerce to issue force majeure certificates to those Italian manufacturers that requested them and were affected by lockdown provisions; through this measure, MISE was aiming to facilitate force majeure claims in international contracts entered into by Italian firms. These certificates constitute evidence that a force majeure event has occurred, but whether this form of evidence is conclusive depends on a number of factors, including the language of any force majeure clause in the contract, the governing law of the contract, and applicable international commercial law.

Conclusion

During the height of the Covid-19 crisis in the U.S. and other jurisdictions last year, some market participants threatened to refuse performance on their contractual obligations citing force-majeure-type arguments as a result of the pandemic. The same happened in the petrochemicals market as a result of extreme winter weather in Texas in February 2021. Studying these events helps us assess the implications of unexpected widespread disruptions. If enough market participants invoke force majeure and their claims result in disputes before the courts, there could be systemic implications. If parties to contract disputes stop meeting margin calls and cease making settlement payments, losses could spread through the financial markets while the bilateral disputes get resolved in the courts—which in some cases could take years.

With that said, a year and a half after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I conclude that there is a low likelihood of force majeure claims creating a systemic threat to financial stability under the current circumstances.

Notes

1 This Chicago Fed Letter does not constitute legal advice. I address some legal concepts for the sake of completeness, with a view to study the systemic impact of certain legal provisions, rather than to provide legal advice. I thank John Spence, former financial markets analyst at the Chicago Fed, and Jahru McCulley, financial markets analyst at the Chicago Fed, for their support in the research for this article.

2 Typically, if the contract lists a series of events that constitute force majeure (e.g., floods) and the specific event claimed (e.g., a pandemic) is not included in that list, the court may find that the clause does not protect that party in the specific circumstance that was not enumerated in the contract. Many contracts do not list pandemics as a type of force majeure, and in that case, it remains to be seen whether the clause will be enforceable based on the wording of the clause.

3 For a forward TBA trade, the particular securities to be sent by a seller to a buyer are determined just before delivery, instead of when the trade is originally completed. More details on TBA MBS are available online.

4 See, e.g., the emergency powers under NYMEX Rule 230.k, available online.

6 See, e.g., this CBOE press release.

8 Firms with an aggregate uncleared derivative exposure value exceeding 50 billion euro will have to comply starting in September 2021, and those with an aggregate exposure exceeding 8 billion euro will have to comply starting in September 2022; see pp. 2 and 24 of this document.