Researchers have long studied the costs to workers of major shocks to businesses like plant closures, new regulations, or international trade. Less understood, however, is how one common and frequent shock plays out in the lives of thousands of workers each year: The several dozen bankruptcies of publicly traded corporations that happen annually in the United States.1

In a forthcoming article in the Journal of Finance co-authored with John R. Graham of Duke University, Si Li of Wilfrid Laurier University, and Jiaping Qiu of McMaster University, we quantify a significant, long-term decline in worker earnings that results from bankruptcy. Further, while some workers demand and receive higher wages before bankruptcy, this “wage premium” isn’t always large enough to offset future losses for workers, especially for those with more limited alternative job prospects.

As the first study that uses microdata on U.S. bankruptcies and affected workers to quantify these outcomes, we hope to shed light on how bankruptcies can affect both workers and corporate decision-making.

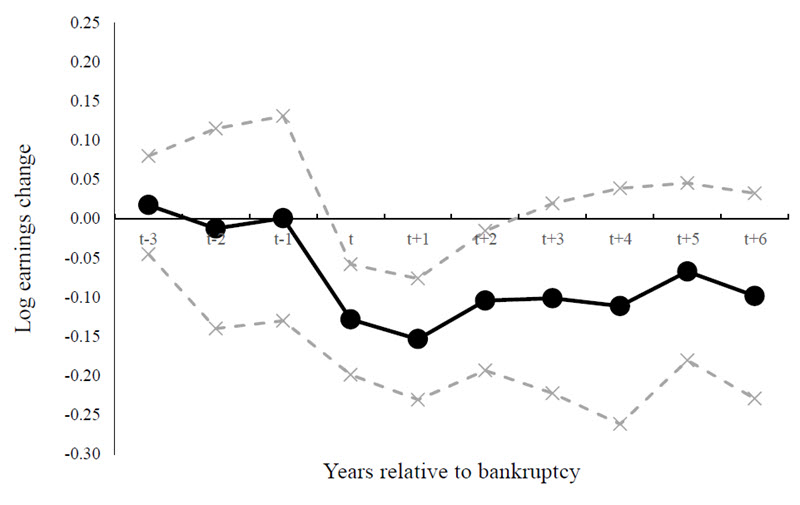

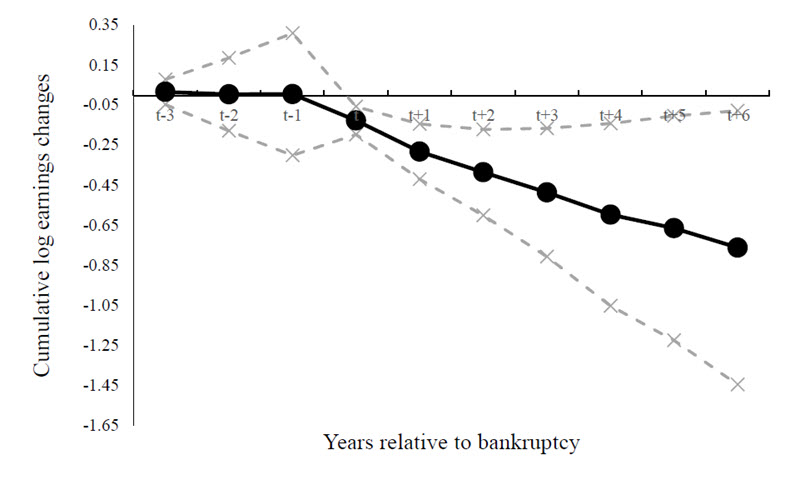

When companies go bankrupt, employees see short- and long-term earnings losses

To understand how bankruptcies affect a company’s employees, we built a dataset of 130 bankruptcy filings by U.S. public companies from 1992 to 2005 and followed, for up to six years, approximately 234,000 workers who were employed by the bankrupt companies one year before bankruptcy.

Our findings suggest that the average employee sees a 13% drop in earnings the year the company files for bankruptcy. The cumulative lost earnings over the next six years, which take into account state unemployment insurance benefits employees receive, amount to 87% of what similar workers make annually at similar companies that did not declare bankruptcy.

How Employee Earnings Fare after Corporate Bankruptcy: Changes

How Employee Earnings Fare after Corporate Bankruptcy: Cumulative Changes

Importantly, we find that employees who leave the company or industry post-bankruptcy, and who worked in labor markets with fewer workers before bankruptcy, see much larger earnings losses. This suggests that for workers whose skills are company or industry-specific or who need to relocate to find similar work, corporate bankruptcies can be especially detrimental.

Beyond what this means for worker welfare, this finding is informative because it suggests employees of companies at higher risk for bankruptcy may have less motivation to develop specialized, company- or industry-specific skill sets that many companies rely on.

To retain workers, companies with a higher risk of distress pay higher wages—but not all workers receive a large enough benefit

When companies take on additional debt to finance activities—a potential indicator of risk of future financial distress—they face a trade-off. Though the additional debt comes with tax benefits, companies also face new costs that may limit the amount of debt they want to take on. For example, corporate finance literature has long understood that companies with financial distress risk should pay workers higher wages—or a “wage premium”—in order to retain them despite the risk of bankruptcy.

In our paper, which is the first to use worker-level wage data2 to directly estimate the wage premium, we uncover two notable findings.

First, consistent with our previous finding that bankruptcy results in larger earnings losses for workers at smaller companies and in labor markets with fewer workers, we find that the wage premium is also higher for these workers. However, we also find strong evidence that the total size of the wage premium is limited by the lack of worker mobility. Specifically, the premium is more prevalent for workers who recently moved between companies than for those who didn’t, suggesting companies pay a smaller wage premium when workers have less ability to move between jobs.

Second, we estimate that the wage premium amounts to a considerable fraction of the tax benefits companies receive. When a company’s corporate credit rating decreases from AA to BBB after taking on additional debt, the tax benefits increase by about 2.7% of company value. For that same company, the increase in the wage premium can be as large as 2% of company value.

Tax policy changes can address these problems—but there are trade-offs for workers

Taken together, our findings suggests that companies with substantial distress risk are transferring a significant amount of that risk to their employees.

Although some employees are compensated for this risk transfer in the form of higher wages, the wage premium may be inadequate for many—especially for workers who cannot easily move to new jobs.

Changes in tax policy can address this problem, but there are trade-offs for workers. Ultimately, our research suggests that if tax policy reduces incentives for companies to take on debt—for example, policies that ultimately limit the tax deductibility of debt—workers may have greater job security, but also be paid less. On the other hand, tax policies that reward leverage can result in higher wages for workers at companies with distress risk, but at the expense of job security.

By using micro data to quantify the labor market outcomes and wage premiums associated with distressed companies, we hope to provide information of value to both workers and company leadership.

To learn more, you can download the full paper.

1 Source: The UCLA-LoPucki Bankruptcy Research Database, 1998-2021 (https://lopucki.law.ucla.edu/).

2 Data comes from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer Household Dynamic (LEHD) program.