The federal government’s propagation of redlining, beginning in the 1930s, is typically attributed to two housing finance programs established in that decade: the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). In a recent paper, co-authored with Price Fishback of the University of Arizona, Ken Snowden of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and Thomas Storrs of the University of Virginia, we seek to better understand the historical role of each agency in propagating redlining.

We conclude that, to the extent that the red lines drawn on maps by the federal government had impacts on the mortgage market, the red lines drawn by the FHA were likely far more impactful than the HOLC’s. We find that the FHA largely excluded core urban areas and Black mortgage borrowers from its insurance operations, while the HOLC did not. In addition, while the HOLC’s maps of urban areas remain iconic symbols of systemic racism, our analysis suggests that it is very unlikely that the HOLC maps were used to guide the mortgage market activities of either the HOLC or the FHA. Instead, the FHA developed its own methodology to redline core urban neighborhoods, which it did from day one of its operations.

From a policy perspective, it is remarkable that these two programs were founded around the same time but developed such contrasting patterns of activity in mortgage markets. We suggest that each agency’s pattern of activity was a function of its legislative mandate. Nevertheless, because each agency possessed administrative flexibility in interpreting its mandate, empirical analysis of actual activity is essential.

Timeline of activities by the HOLC and FHA

In 1933, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) as a temporary program with a mandate to aid mortgage borrowers who, given economic circumstances during the Great Depression, were in hard straits through no fault of their own.

The next year, in 1934, the federal government established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) as a permanent agency with a mandate to insure loans that were “economically sound,” while also requiring private lenders to offer lower interest rates and longer durations than were typically available. The FHA was also intended to focus on financing new construction, in order to revive the building industry.

Both agencies developed maps that evaluated urban neighborhoods. The HOLC maps have received intense study in part due to their careful preservation. In contrast, the FHA’s maps have been destroyed. On the HOLC maps, predominantly Black neighborhoods were as a rule marked “red”—the lowest rating. Many studies have concluded that the HOLC maps propagated discriminatory lending practices against Black Americans and other low-income urban residents by institutionalizing existing redlining practices.

Evidence of federal propagation of redlining within the Federal Housing Administration

We digitize over 16,000 loans made by the HOLC or insured by the FHA in three U.S. cities, covering all loans made by the HOLC from 1933 to 1936, or insured by the FHA from 1935 to April 1940.1 Using these data, we have two main findings.

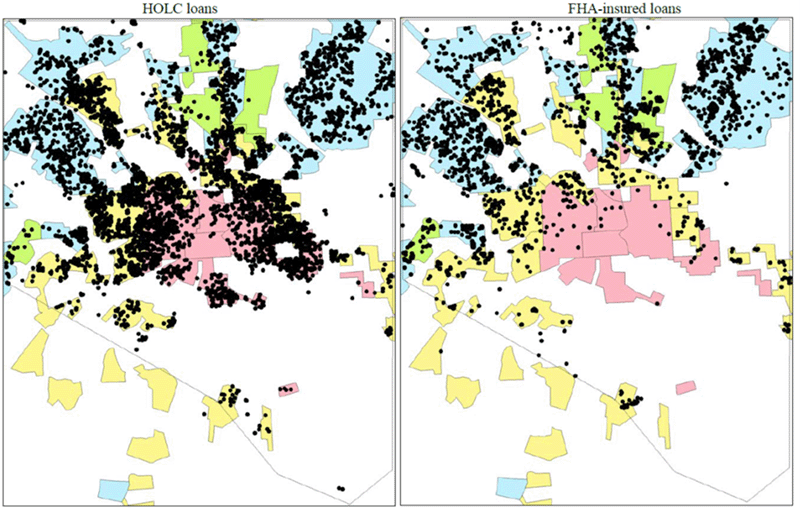

First, the HOLC and the FHA had very different patterns of activity. In each city, the HOLC made many more loans to neighborhoods in areas eventually rated C or D (“red”) on their maps compared to the FHA. In addition, the share of HOLC loans to borrowers who were Black was largely proportionate to the share of homeowners who were Black. In contrast, the FHA largely excluded Black borrowers and core urban neighborhoods, and instead targeted areas with new construction and higher property values. For example, figure 1 shows the pattern of HOLC and FHA activity in Baltimore.

1. HOLC loans (1933 to 1936) and FHA-insured loans (1935 to 1940) in Baltimore, MD, superimposed on the 1937 HOLC map

Second, the HOLC maps were created after these patterns had already been established. The HOLC had already made 90% of its loans before its map project began in 1935. Likewise, the FHA began insurance operations before the HOLC’s map program was launched. We find that the FHA excluded core urban neighborhoods and Black borrowers from day one of its operations, and that its practices showed little change after the HOLC maps were created.

Lessons for policy on mandates and agency operations

How is it possible that these two New Deal programs had such different footprints in mortgage markets? While they were designed and enacted within a year of each other by the same Congress and presidential administration, they had differing policy mandates.

While the HOLC broadly loaned to Black borrowers, it did so within the existing system of segregation, refinancing loans that already existed. In contrast, the FHA was instructed to create a new system of loan insurance that departed in key ways from existing practices. In light of the failure of mortgage insurance companies from the 1920s, the FHA was instructed to make only “economically sound” loans—a phrase that the FHA interpreted as a mandate to avoid core urban neighborhoods or those whose racial composition might potentially be in flux. Neither program was tasked with defying the existing patterns of segregation, and neither did.

An unusual cluster of FHA-insured loans from our study drives home this point. In Baltimore between 1935 and 1940, we find only 25 Black households that received loans insured by the FHA (compared to hundreds of loans to Black borrowers made by the HOLC). A large share of these FHA-insured loans went to households in Morgan Park, an upscale neighborhood near the historically Black educational institution now known as Morgan State University. Morgan Park appears to have been the rare Black neighborhood that satisfied the FHA’s underwriting criteria, with restrictive covenants barring White occupants and newer, high-quality suburban-style housing.

Our research leaves no doubt that the existence and legacy of redlining is real. We argue, however, that to the extent that federal agencies institutionalized redlining by drawing specific borders, this largely occurred through the FHA.

To learn more, please download the full working paper.

Note

1 Our sample of loans come from county offices in Baltimore City, Maryland; Peoria, Illinois; and Greensboro (Guilford County), North Carolina.