During the 1980s and early 1990s, high crime rates led many states to pass laws that mandated or encouraged judges to send more people to prison. These laws were so much stricter than previous laws that, despite a significant reduction in crime over the past 30 years, current incarceration rates are roughly 300% higher than their 1980 levels. However, a new research paper by Andrew Jordan of Washington University in St. Louis, Ezra Karger of the Chicago Fed, and Derek Neal of the University of Chicago finds that for a large share of the prison population, prison time isn’t the crime deterrent many people think it is.1

The study, which analyzes 70,581 felony court cases filed in Chicago from 1990 to 2007, is among the first to compare sentencing outcomes between those in the criminal justice system for a first offense and those in the system for a repeat offense. By analyzing the impact of prison and other sentencing measures on these two groups, the researchers uncover some important new findings.

Toward a better understanding of repeat offending

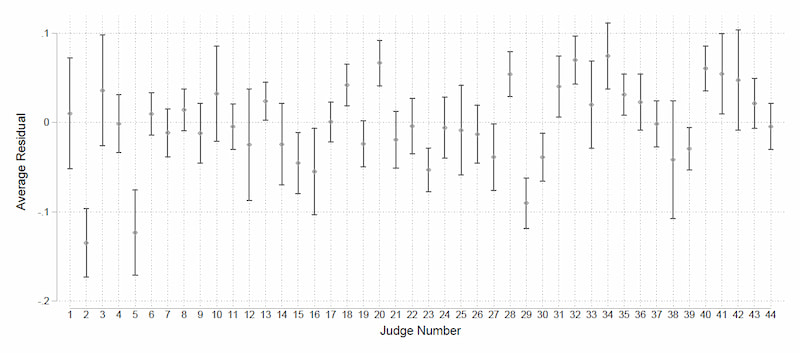

To conduct the study, Jordan, Karger, and Neal divide the sample of defendants into two groups: those facing their first felony charge and those who faced at least one other felony charge in the past. Within the samples of people with first and repeat offenses, they study cases that the court randomly assigned to judges.2 Judges vary greatly in the average severity of their sentencing practices, and the study uses this variation to measure the impacts of differences in sentences given to similar defendants.

Jordan, Karger, and Neal ultimately uncover the following: When people with repeat offenses are charged with a new felony, those who go to prison are just as likely to be charged with at least one future felony during the next seven years as comparable people with repeat offenses who receive non-custodial sentences. In contrast, they find that incarceration deters future crime among people with a first offense. This deterrence effect is particularly strong among those whose first offense is not a drug crime and who do not live in areas with relatively high rates of crime. But, among people with repeat offenses of any type, the study finds no evidence that prison time creates lasting reductions in their chances of interacting with the criminal justice system in the future.

In both population samples, the study finds considerable variation in sentencing outcomes among people charged with the same crime, and much of this variation is driven by the random assignment of judges to cases. When dealing with a person charged for the first time, some judges are much more severe than others, and some judges are far more severe or lenient when sentencing people who face charges more than once. Further, the judges who are most severe with those charged repeatedly are often not the judges who are most severe with those charged for the first time. Taken together, these patterns imply that the likelihood of receiving a prison sentence is heavily influenced by random judge assignments.

First Offenders

Repeat Offenders - Sorted by Judge Severity Among First Offenders

Over-policing does not explain why people sentenced to prison are so likely to reoffend

Parole officers in Illinois have the power to arrest persons on parole if they suspect they are involved in criminal activity, and people with repeat offenses are more likely than those who only have been charged with a first offense to live in high-crime neighborhoods and to be charged with drug crimes. So, some may conjecture that prison fails to reduce the likelihood of future felony charges among people with repeat offenses because they are over-policed while on parole. However, Jordan, Karger, and Neal find no evidence to support this hypothesis. Being under the supervision of parole agents does make it more likely that people return to prison, but this increase in prison re-entries is entirely due to technical violations of Illinois’s Mandatory Supervised Release (MSR) conditions. They find no evidence that people are more likely to be charged with a new felony while under MSR supervision.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings illustrate that people who face charges repeatedly interact with the criminal justice system differently than those charged with a first offense. Since the vast majority of inmates in state prisons have been charged more than once, these results underscore the need for crime reduction efforts to focus on the promise of reintegration and rehabilitation. This study also highlights the importance of further research to compare sentencing outcomes by race, especially since those with repeat offenses in the sample are more likely to be Black. In this particular study, data limitations prevented the researchers from comparing the effects of sentencing outcomes for different racial and ethnic groups.

To learn more, download the full paper.

Notes

1 I would like to thank Ezra Karger, Delaney Parrish, and Helen Koshy for their contributions to this research brief.

2 Importantly, Jordan, Karger, and Neal focus on crimes that are randomly assigned to judges and exclude from their study crimes that are not randomly assigned, such as felony murder and political corruption.