During the first three quarters of 2005, the U.S. economy grew at a rate about equal to or slightly above its potential growth rate - the rate that can be sustained over the long run without creating inflation pressures. Real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2005, however, dropped to an annual rate of below 2 percent. This appears to have been largely due to transitory factors, and various indicators point to a recovery in growth in early 2006.

When the economy has an abundance of slack resources, as it did after the 2001 recession and the slow recovery that followed, inflation pressures can remain relatively muted even when the economy grows faster than its potential. Over the last couple of years, a highly accommodative monetary policy has helped foster such economic growth, which has removed much of this slack. The unemployment rate has fallen from almost 6 percent at the end of 2003 to under 5 percent at the end of 2005, and the capacity utilization rate in manufacturing has risen from under 77 percent at the end of 2003 to over 80 percent at the end of 2005, near its 30-year average.

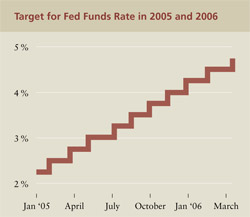

With the economy growing at a robust, self-sustaining rate, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) began removing policy accommodation at a measured pace in June 2004 to prevent inflation pressures from developing. This continued throughout 2005, with the target federal funds rate (see chart below) rising from 2.25 percent at the beginning of 2005 to 4.75 percent after the FOMC meeting in late March of this year, the first one led by new chairman Ben Bernanke, who replaced Alan Greenspan.

|

| The target Federal Funds rate rose from 2.25 percent at the beginning of 2005 to 4.75 percent after the FOMC meeting in late March of this year. Source: Federal Reserve System |

Soaring energy prices are also an inflation threat. Spot crude oil prices jumped over 30 percent in 2004, and strong worldwide demand, continued geopolitical risks, and the terrible devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina contributed to a 40 percent increase in oil prices in 2005. Natural gas and refined oil product prices also rose sharply in 2005. Like other costs related to production, higher energy prices can pass through to the prices of other goods and services.

Finally, there is a concern that if people see a string of higher inflation numbers, they may begin to expect permanently higher inflation. Though inflation expectations are currently contained, one of the goals of monetary policy is to keep these expectations in check.

Some have suggested that explicit numerical inflation guidelines can aid the Fed in keeping inflation expectations well anchored at a low level. In this year's annual report, we examine the issue of inflation targets in more detail and pose some questions that need to be answered before I feel we can make a final determination on this issue.

2005 Results and Recognition of our Employees and Directors

The hard work and dedication of our employees and the leadership and counsel of our directors in 2005 contributed to another successful year at the Chicago Fed. A list of some of our many accomplishments.

Two individuals completed their service as directors last year and merit separate mention: Connie E. Evans from the Chicago board and Edsel B. Ford II from the Detroit board. Both Connie and Edsel served on their respective boards since 2000, and Edsel served as chairman of the Detroit Branch board for the last two years. I am personally grateful to both for their valuable perspective and guidance. On a related note, Valerie B. Jarrett, managing director and executive vice president of the Habitat Company, joined the Chicago board this year, and Timothy M. Manganello, chairman and CEO of BorgWarner, Inc., joined the Detroit board.

I would also like to recognize Alan Greenspan, whom I have known for over 35 years, for his more than 18 years of outstanding service as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board and the FOMC. His contributions will be missed, but I have high regard for his successor, Ben Bernanke. And Chairman Bernanke is taking over a very strong institution. The quality of the people at the Fed and the collegial nature of this organization will continue to contribute to our success in 2006.

Michael H. Moskow

President and Chief Executive Officer

April 1, 2006

Monetary policy has come a long way in the past quarter century. Price stability has always been part of the Federal Reserve's policy mandate, and one of our major accomplishments of the last 25 years is that we have actually achieved this goal.

We have learned a lot about monetary policy during the last 25 years - and we're still learning. We have gained important insights about the tactics of monetary policy as we moved from an environment of moderate inflation to one of price stability. In particular, we have learned a good deal about the benefits of maintaining appropriate flexibility when implementing policy. We also have learned about the importance of communications and transparency in that implementation - notably their role in reducing the uncertainty that households and business owners face when making economic decisions such as how much to spend, save and invest, or what prices to charge for their products.

Some argue that the best way for central banks to increase transparency and reduce this uncertainty is by adopting explicit numerical targets for inflation. However, there are a number of outstanding questions that should be addressed before a central bank decides to move to a regime of explicit numerical guidelines. Importantly, central banks usually think about these questions only in terms of achieving a target for inflation. But the Federal Reserve has two goals: It is charged with the dual mandate of fostering maximum sustainable growth as well as price stability.

Economists have thought a lot about these questions in recent years. In my opinion, they have not yet come up with adequate answers. So these questions continue to challenge a wide range of experts: academic researchers who study monetary theory, economists who advise businesses and households on how monetary policy may affect their investment decisions, and central bankers who try to formulate effective monetary policy in a constantly changing - and inherently uncertain - economic system.

The Tactics of Monetary Policy During the Transition to Price Stability

When thinking about the interaction between inflation and monetary policy, it's useful to remember University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman's important observation: Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. I learned this lesson the hard way in the early 1970s when working at the Council of Economic Advisers and at the Council on Wage and Price Stability. Overly expansive monetary and fiscal policies had contributed to a rise in inflation from near 1 percent in the early 1960s to more than 6 percent in early 1970. These rates were unacceptably high, and wage and price controls were implemented in 1971 to deal with the problem.

These controls did more harm than good. They did not break inflationary expectations, and inflation rates spiked back up when the controls were lifted. Furthermore, the distortions to relative wages and prices caused by these policies - and by other controls and guidelines that followed - resulted in the misallocation of productive resources in the economy.

Today, many of those involved in implementing wage and price controls have vowed to fight fiercely any future efforts to reinstate them. But that certainly was not doctrine back then. For example, in the 1970s, Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns thought that monetary policy should not take sole responsibility for bringing down inflation. He believed some kind of wage and price review authority was a necessary additional element of anti-inflationary policy. The experiences of the 1970s, however, stress that anti-inflationary efforts outside of the realm of monetary policy are far less important for lowering inflation than reversing the accommodative policies pursued by the Fed.

Much hard-fought progress against high inflation had occurred by the time of my arrival at the Chicago Fed in September 1994. At that time, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was embarking on a pre-emptive strike against emerging price pressures in order to prevent inflation from rising. These policy moves were successful. Subsequently, a series of events resulted in the achievement of price stability.

The history of this 11-year period highlights the importance of flexibility in the implementation of monetary policy. Part of this flexibility is the willingness to debate and discuss new ideas. A good example is the tactical discussion in 1995 and 1996 about opportunistic disinflation. This was a discussion about whether policymakers should deliberately move to lower inflation or whether they should wait for the reductions that typically occur when the economy softens somewhat. In other words, should the effort to reduce inflation involve daily skirmishes or less regular battles when the opportunity arises?

Interestingly, opportunism won out in a different way. The opportunistic arguments in the mid-1990s largely were based on the idea that inevitable slowdowns in aggregate demand could be exploited to lower inflation. In fact, the productivity acceleration during the second half of the 1990s allowed for lower inflation without reductions in aggregate demand or economic activity — inflation came down at the same time that unemployment was falling. But because productivity growth had been persistently slow for the previous 20 years, few people considered the possibility of a productivity resurgence at the time of the opportunistic-versus-deliberative policy debate.

The next episode that is important to highlight occurred in 2003. Following its May 2003 meeting, the FOMC acknowledged a relatively new risk to the economy: the possibility of an unwelcome fall in the inflation rate. For a central bank that had worked steadily for 25 years to reduce inflation, this sure was something new. But it highlighted the fact that with the achievement of price stability, monetary policy had to be based on flexible thinking; it had to acknowledge that inflation could be either too high or too low. And policy had to be conducted in recognition of that fact.

These episodes are well-known to business and monetary economists who have studied the path that the U.S. economy has followed to reach the neighborhood of price stability. Interestingly, it is a peculiarly American path.

While other central banks pursued a numerical inflation objective, the U.S. achieved price stability without having an explicit numerical target. Of course, it wasn't that important to have a numerical definition of price stability when actual inflation exceeded price stability by everyone's measure. At the time, Chairman Alan Greenspan offered a useful, though non-explicit, definition: It's when businesses and households are not taking inflation into account in their economic decisions. So as long as the plans of households and businesses still accounted for inflation, it seemed clear that price stability had not yet been reached.

Furthermore, while other countries have suffered sluggish growth to achieve lower inflation, the U.S. did not. This is because our disinflationary monetary policy could be implemented against the backdrop of a step-up in productivity growth and because monetary policy did not adhere to a rigid mechanical rule, but adapted to the incoming evidence on inflation and output.

This flexibility has been an important hallmark of monetary policy tactics over the past 20 years. This has caused heartburn among academics and others who worry about excessive discretion and advocate a more rigid, rules-based policy. Instead, the Greenspan Fed generally has responded adeptly to changing economic conditions and financial risks that threatened macroeconomic performance, and has done so without abandoning the discipline of its dual mandate to pursue maximum sustainable growth and price stability.

The Fed's reaction to financial risk is another hallmark of flexible policy. This actually is an old prescription for central bankers that Walter Bagehot (the founding editor of The Economist) gave in the 19th century: Provide liquidity to solvent financial institutions during financial market crises. Such action was clearly evident during the stock market crash of 1987, the extended monetary accommodation in the face of financial headwinds of the early 1990s, the Russian default in 1998, and the period after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

In some instances, the injection of liquidity ran counter to the inflation risks that the FOMC perceived just before the crisis. But as events bore out, such flexible monetary policy responses did not jeopardize the pursuit of the nation's long-run goal of price stability. That is because an important element in this "disciplined approach to flexibility" is that long-run policy goals generally have been clearly articulated and are understood by the public.

The Importance of Communications and Transparency

Another relevant topic is the importance of communications and transparency in the implementation of monetary policy. The changes that have occurred in this area are little short of extraordinary. Remember when central bankers deliberately avoided announcing their decisions? Over the past decade, we have seen a move from central bank secrecy to central bank transparency, a change that reflects a growing appreciation of the enhanced policy credibility and reduced economic uncertainty that accompany public understanding of the goals and rationales underlying monetary policy decisions.

It was not until 1994 that the Fed decided to announce policy changes immediately following FOMC meetings (See The Evolution of Federal Open Market Committee Communication). The first one went like this: "The Federal Open Market Committee decided to increase slightly the degree of pressure on reserves. The action is expected to be associated with a small increase in money market rates." The key word was "slightly," and there was no explicit mention of the federal funds rate. The next step in the evolution of the policy communication was the explicit mention of the target federal funds rate. Then came the announcement of a "tilt" to indicate the likely direction of the next policy move, then the judgment of the balance of risks to the policy objectives, then discussion of two-sided inflation risks, and, finally, the accelerated release of the minutes of FOMC meetings. In addition, media coverage of all FOMC participants' speeches has exploded, and the Internet makes these readily available to everyone in real time. So, even though there is no rigid numerical rule, the public has a much better idea of the systematic ways in which the committee makes judgments regarding economic developments and translates these into monetary policy decisions.

Although transparency requires careful execution of communications strategies, its benefits seem obvious: the well-anchored inflationary expectations and reduced uncertainty mentioned earlier. When the public and financial markets have a clear understanding of Federal Reserve goals and the methods used to achieve these goals, uncertainty is reduced, and consumers and businesses can better plan for future activities. One way this is revealed is in borrowing costs: Policy transparency can lower the risk premia imbedded in interest rates because it reduces the uncertainty over how future rates may vary due to changes in inflation, economic activity, and monetary policy.

Appropriately, there will always be risks for entrepreneurs in search of returns, but central banks should not add to those risks by unnecessarily increasing uncertainty regarding monetary policy. At the same time, though, they should not lead markets to think that the path for policy is more certain than it actually is. Finally, when policy is transparent, a central bank can respond to economic events and financial crises that involve liquidity shortages without creating undue risk - the bank can make it clear to markets that it is responding to a short-run problem and not lessening its commitment to price stability.

Questions Regarding Explicit Numerical Guidelines

An important question facing central bankers involves determining the best way to be transparent and communicate policy. Some say explicit numerical guidelines are the ultimate form of transparency and communication, arguing that these guidelines are the best way for a central bank to anchor inflationary expectations and reduce the uncertainty over the future path for policy and interest rates (See Selected Central Banks' Inflation Guidelines). This leads to a third important topic: the questions that remain to be addressed regarding the advantages and disadvantages of explicit numerical regimes.

It's pretty much accepted now by economists that monetary policy cannot permanently alter the unemployment rate or growth rate of the economy. This is often referred to as the vertical, or expectations-augmented, long-run Phillips curve and the natural rate hypothesis of Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps. According to this hypothesis, attempts by monetary policy to push unemployment below its natural, or equilibrium, rate eventually will lead to pressures on resources and rising inflation and inflationary expectations. The unemployment rate will need to return to its equilibrium level in order to stabilize inflation.

Now it wasn't so long ago that the Humphrey-Hawkins Act placed explicit guidelines on the achievement of both low inflation and maximum employment. The law was enacted in 1978 when the natural rate hypothesis was more controversial. The Humphrey-Hawkins Act set the following targets for unemployment and inflation within five years of the act's passage: the unemployment rate would be below 3 percent for those older than 19 and below 4 percent for those 16 years old and up; and CPI inflation would be under 4 percent. And the law also stated that by 1988 the inflation rate was to be zero percent.

Well, the unemployment rate didn't drop to 4 percent by 1983, and the inflation rate wasn't down to zero by 1988. Fortunately, though some would have liked it, the Fed was not held in contempt of Congress.

Of course, no one on the FOMC is suggesting that numerical targets for unemployment be reinstated. But FOMC members have expressed a variety of views on numerical inflation measures. Some have suggested an explicit inflation guideline. But no one has proposed full-blown inflation targeting in which we would commit to set policy with the sole aim of achieving a particular numerical inflation rate within some predetermined time period.

As an aside, the open discussion the FOMC has had on explicit inflation guidelines has been very healthy. Such debates are a strength of the Federal Reserve and foster much learning. So no matter what the final decision, our discussion of inflation guidelines will help formulate more informed — and better — monetary policy.

In any event, some form of an explicit numerical guideline may be embraced some day. But there are many issues that need to be studied and questions that need to be answered before making this decision.

The first problem is deciding what the number should be. As noted earlier, former Chairman Greenspan offered a non-explicit definition of price stability: when households and business owners are not taking inflation into account in their economic decisions. This is a useful definition, but it does not easily translate into a particular number for an inflation guideline.

Indeed, as recent history shows, deciding on a number for policy to aim for - let alone if it represents price stability or not - has been the subject of a good deal of debate. There was little debate in the late 1980s. Inflation was around 4-1/2 percent and looked to be heading up - to most, the inflation outlook clearly was too high. However, there was a debate in 1994. Core CPI inflation then was a relatively low 2.8 percent, and according to the minutes and transcripts, inflation was generally heading higher than most FOMC participants wanted. But that view was not universal. Many commentators thought an inflation rate of 3 percent was satisfactory and the Fed should not try to reduce it.1 Today, though, it's doubtful many people would find 3 percent to be an acceptable point estimate for an inflation guideline. Of course, as I noted earlier when describing policy during 2003, it is possible for inflation to be too low. Importantly, the zero bound on nominal interest rates means that if inflation were too low, the Fed could be limited in its ability to lower short-term real interest rates and thus would have to turn to alternative and largely untested methods if it found it necessary to respond to unfavorable shocks to the economy.

A related question involves a seemingly simple issue: Which index should be selected for the inflation guideline? There are many measures of inflation: the Consumer Price Index, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index, and the GDP price index, to name only a few.2

When inflation rates are high, it typically doesn't matter which index is selected for the guideline, because all measures of inflation will be high and above the guideline. But when inflation is in the range of price stability, the choice of the index could matter. Indeed, seemingly small differences in the composition of consumption baskets and other measurement methods in principle mean that different indexes could conceivably send mixed signals to policymakers about the appropriate direction policy should take.

There are other issues with regard to the choice of the guideline index. The Fed thinks that the price index for personal consumption expenditures, excluding food and energy, is the best measure of underlying trends in consumer inflation. But does that mean it's the best index for a guideline? For example, the total CPI is used in many private contracts as well as the inflation adjustments in many tax and transfer programs. So should there be a guideline for the CPI as well? Also, in a period of rapidly rising energy costs - such as the present - will the public have confidence in an inflation guideline that excludes energy prices? Would such a guideline achieve its claimed advantages of anchoring expectations and reducing risk premia?

Another set of issues centers on the best way to specify the numerical guideline to anchor inflation expectations. Should it be a single hard number or should it be a range of inflation outcomes? And once that has been decided, what is the time frame for achieving and maintaining the numerical values? The problem is to come up with something practical, yet still informative.

The advantage of a single number is that it's precise, so that there is no question how far one is from the guideline. However, actual inflation will inevitably fluctuate, and it's extremely unlikely that inflation at any point in time will be precisely at the guideline. To get around this problem, a range of acceptable inflation outcomes could be specified. It's more feasible to achieve inflation rates within a range. Of course, there is the issue of how wide the range should be. A very wide range would be uninformative and therefore not a useful starting point.

Under both systems, however, there are difficulties in communicating policy. In the first instance, it's communicating what kinds of small deviations from the single number policymakers would be willing to ignore. In the second case, it's communicating what kinds of deviations within the range would require a reaction by policymakers. We don't want to leave the public with the impression that there necessarily is a "zone of indifference" about inflation whenever it's in the guideline range. In either case, the difficult communications task would be to explain the role of economic conditions in determining why sometimes the FOMC acts, and other times it doesn't.

Furthermore, the policy prescription needs to include a time period for evaluating the inflation outcome against the inflation guideline. Empirical evidence indicates that monetary policy does not affect the trajectory of inflation before one year, or more likely, two years. So it's impractical to specify too short of a time period to reach the guideline. In contrast, suppose a very long time period is specified, say 10 to 20 years. It's doubtful that households and business owners would find this very useful for their financial planning. Obviously, the answer lies somewhere in between. Many central banks that have guidelines refer to the time frame with the qualitative phrase of "over the medium term." It is difficult to say precisely what this means. Is it three years, or five, or 10? And is it even a constant time period?

The time-frame decision becomes even more complicated when one considers another important issue: the Fed's dual mandate.

How does our growth mandate interact with a numerical guideline for inflation? As seen with the Humphrey-Hawkins Act, achieving explicit fixed guidelines for unemployment or real GDP growth is not workable in practice. Theoretically, the equilibrium, or natural, rate of unemployment and the trend in potential GDP growth change over time with demographics, productivity trends, and other factors. For example, a decline in the trend in productivity of the labor force would reduce the potential growth rate of GDP - and trying to boost output growth higher would only generate inflationary pressures. Furthermore, there are many issues regarding the measurement of these concepts. In any event, monetary policy cannot alter the natural rate, and any influence on potential output from the risk premia channel is at most secondary. As those in Europe are learning, reductions in high rates of structural unemployment require regulatory changes and increased competition. Paradigm changes are needed to remove structural impediments to growth and employment.

But even if it is accepted by economists that it does not make sense to set explicit fixed numerical targets for real growth and unemployment, the dual mandate still puts equal weight on price stability and maximum employment. In the academic literature on inflation targeting, a central bank that places substantial weight on both targets is referred to as a "flexible inflation targeter."

As of yet, in my opinion, the proposals for flexible inflation targeting require further elaboration before they can be of practical use to policymakers. Suppose for the sake of argument that the natural rate of unemployment and the level of potential real GDP were known. The key question in formulating explicit guidelines in the context of the dual mandate has two parts: "How fast should we plan to close the deviation in inflation from price stability?" and "How fast should we close the deviation between the unemployment rate and the natural rate?"

The answer is complicated because it involves the interaction between the time frame for closing any gap between actual output and its maximum sustainable level and the time frame for bringing inflation in line with price stability. This is because policy dilemmas may arise. Suppose inflation is one percentage point above its guideline. If output is above potential, then there is no policy dilemma, because a contractionary policy aimed at both slowing output growth and reducing inflation would make progress on both objectives. But if output is below potential, there is a conflict in achieving both objectives. The inflation gap points to raising rates, while the output gap suggests lowering them. Flexibility means that the central bank must balance the two deviations; therefore, it would take longer to close either gap in the second case than in the first. And the larger the policy dilemma, the longer it would take to close the gaps.

This discussion highlights the serious, and unanswered, question of how to specify formally such variable time periods in a policy environment with explicit numerical guidelines. Even if this problem is solved, other issues then come into play. As a legal matter, would the Fed need Congressional approval to adopt flexible targeting? And in light of the dual mandate, would this eventually lead to adding numerical unemployment guidelines that - like those in the Humphrey-Hawkins legislation - would prove to be incompatible with the natural rate hypothesis? Finally, how do you best explain flexible targeting to the public? It seems that whenever a number is mentioned, the media focuses entirely on the number and forgets all of the caveats.

This brings me to a final question. Suppose a central bank successfully adopted a formal inflation guideline that respects a dual mandate by flexibly adjusting the time horizons for achieving both its guidelines. Would this policy look any different from current Fed policy? Some academics who study inflation- targeting central banks say no.3 They say that, effectively, the Federal Reserve does engage in flexible inflation targeting. This is a bit puzzling since there are no announced explicit guidelines. Still, financial markets and the public do not seem to be overly bothered by the lack of an explicit number for future inflationary expectations, and at the present time, inflationary expectations are well anchored. Our actual policy appears to have successfully obtained one of the most important benefits ascribed to a regime based on formal guidelines.

Then what is it that distinguishes current policy from simple discretionary ones that have the potential to produce large run-ups in inflation, like those in the 1970s? It's that central bankers now know that even without rigid rules or numerical guidelines, their actual approach to policy must be aimed at keeping inflation expectations anchored at a low level. They see this as a prerequisite to achieving maximum sustainable growth over the long run. Central bankers also know that anchoring inflationary expectations sometimes requires pre-emptive policy tightening before the actual inflation numbers start to rise - moves that might prove unpopular with the public, but are necessary to keep inflation in check.

A lot of questions have been raised in this essay concerning inflation guidelines and flexible targeting. There is not a pressing need to make an immediate decision on guidelines one way or the other. However, the topic is one of the most important issues currently on the table regarding the appropriate strategies for conducting monetary policy. There clearly are many issues regarding guidelines and targeting for researchers, business economists, and policymakers to study and debate. And this debate is going to be a healthy process. No matter what answers surface, more will be learned about the best ways to conduct monetary policy in our complicated and ever-changing economy.

Looking ahead, Ben Bernanke, the new chairman of the Federal Reserve, has been a proponent of more explicit inflation guidelines, and the FOMC clearly will be discussing the issue further. These discussions will take place with full consideration given to formulating such guidelines in the context of maintaining policy flexibility and respecting the Federal Reserve's dual mandate. As Chairman Bernanke said in his confirmation hearings:

"I view the explicit statement of a long-run inflation objective as fully consistent with the Federal Reserve's current policy approach, including its appropriate emphasis on the role of judgment and flexibility in policymaking. Most important, this step would in no way reduce the importance of maximum employment as a policy goal. Indeed, a key justification for this action is its potential to contribute to stronger and more stable employment growth by further stabilizing inflation and inflation expectations. In any case, I assure this Committee that, if I am confirmed, I will take no precipitate steps in the direction of quantifying the definition of long-run price stability. This matter requires further study at the Federal Reserve as well as extensive discussion and consultation. I would propose further action only if a consensus can be developed that taking such a step would further enhance the ability of the FOMC to satisfy its dual mandate of achieving both stable prices and maximum sustainable employment."

Of course, whatever the outcome of this discussion, the FOMC's decisions regarding inflation guidelines will not be the final say on what constitutes the appropriate tactics for conducting monetary policy. Paradigms will continue to shift, and new personalities will arrive on the scene. And central bankers will continue to grapple with the best ways to implement monetary policy and convey to the public how we aim to achieve the fundamental long-run goals of price stability and maximum sustainable growth. Indeed, some people have complained that when Alan Greenspan retired after his extremely successful chairmanship of the Fed, he didn't write down his secret for running outstanding monetary policy - "He didn't leave a playbook." But that's fine - the most important legacies of the Greenspan era may be the lessons that central bankers teach themselves as they reflect on the conduct of monetary policy over the past 18 years.

Center Focuses on Issues Related to Price Stability

The views presented here are those of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Michael Moskow and not necessarily those of the Federal Open Market Committee or the Federal Reserve System. Major portions of this essay are based on a speech presented September 26, 2005, by the author to the National Association for Business Economics. Economic Research Senior Vice President Charles Evans and Vice President Spencer Krane contributed to development of the speech and this essay.

1 A sophisticated expression of this view was offered by George A. Akerlof, William T. Dickens, and George L. Perry, "The Macroeconomics of Low Inflation," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 1 (1996). It is based on the hypothesis that even though real wages determine purchasing power, workers have an extra aversion to seeing real wages lowered through a reduction in nominal wages. This results in nominal wages being sticky on the downside. These authors calibrate a model in which an inflation rate of 3 percent allows most realignments of real wages to occur without reducing nominal wages.

2 Most central banks that have targets use a consumer or retail index, and this has some grounding in economic theory since it is ultimately the well-being of consumers that matters for utility theory. For example, good business decisions among intermediate goods producers ultimately benefit consumers through their effect on final products and returns to investors who are also consumers.

3 See, for example, Marvin Goodfriend, "Inflation Targeting in the United States," NBER Working Paper no. 9981, September 2003.

Economic Research and Programs

Chicago Fed economists conducted research in support of the monetary policy responsibilities of the Bank's President and Board of Directors, including special presentations on inflation expectations, the Delphi bankruptcy and housing prices.

- The department held 29 conferences throughout the District, and 22 Economic Research papers were accepted for publication in refereed journals.

- The Inflation Research Center sponsored important initiatives, among them a new measure of core inflationary pressures and a new approach to short-term inflation forecasting. The Center also organized a conference on price stability.

Financial Institution Supervision and Regulation

Supervision and Regulation improved core supervisory functions through enhanced risk analysis, staff development and operational processes.

- The department conducted more than 1100 examinations, inspections and off-site reviews. It strengthened its risk-assessment process, putting more focus on improving its analysis of the root causes of institutional risk.

- Supervision and Regulation employees spoke at conferences for the Institute of Internal Auditors, the American Bankers Association and the Bank Administration Institute. The department also organized a conference bringing together community bank CEOs from around the five-state region.

Financial Services

Seventh District cash and check processing performed well during the year.

- Seventh District check revenue goals were exceeded by 15% based upon volumes and increased usage of Check 21 image products.

- The Detroit Branch maintained strong performance while shifting its check-processing operations to Cleveland as part of the ongoing effort to consolidate and streamline Federal Reserve financial services.

- With the cooperation of the Secret Service, the U.S. Coast Guard and three other law enforcement agencies, the Detroit Branch moved more than $1 billion into its new state-of-the-art facility (see photo above left).

- The Midway Facility implemented a quality management program to help improve efficiency. Special attention was paid to managing float and developing Check 21 expertise.

- The Des Moines office sustained high productivity all year and scored well on performance and cost measures. In a key indicator of quality control, the internal error rate was among the lowest for check processing in the Federal Reserve System.

Customer Relations and Support Office (CRSO)

The national office at the Chicago Fed that provides support to Federal Reserve customers nationwide made progress in converting customers to FedLine Advantage, a new electronic access solution.

- More than 3,000 institutions were conducting transactions daily via FedLine Advantage by year-end.

Other Activities

- Money Smart Weeks held in Chicago and Detroit featured more than 700 events that provided financial education to more than 25,000 area consumers.

- Record attendance by Federal Reserve executives around the U.S. highlighted the System's annual leadership conference, which was developed and hosted by the Chicago Fed. The Bank also sponsored similar leadership training for other management staff.

1994 FEBRUARY

First Press Release After a Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) Meeting.

"Chairman Greenspan announced today that the Federal Open Market Committee decided to increase slightly the degree of pressure on reserve positions. This action is expected to be associated with a small increase in the short-term money market interest rates. The decision was taken...in order to sustain and enhance the economic expansion...."

1995 JULY

First Explicit Mention of the Target for the Federal Funds Rate.

"Chairman Alan Greenspan announced today that the Federal Open Market Committee decided to decrease slightly the degree of pressure on reserve positions....Today's action will be reflected in a 25 basis point decline in the federal funds rate from about 6 percent to about 5-3/4 percent."

1999 MAY

Begin Releasing an Announcement Following Each Meeting Even if There is No Change in the Policy Rate. Announcements Now Include A Description of Economic Conditions. A "Tilt" is Added to Indicate Likely Direction of Next Policy Move.

"While the FOMC did not take action today to alter the stance for monetary policy, the Committee was concerned about the potential for a buildup in inflationary imbalances that could undermine the favorable performance of the economy and therefore adopted a directive that is tilted towards the possibility of a firming in the stance of monetary policy. Trend increases in costs and core prices have generally remained quite subdued. But domestic financial markets have recovered and foreign economic prospects have improved since the easing of monetary policy last fall...."

2000 FEBRUARY

"Tilt" Replaced with Balance of Risks to Policy Goals.

"...Against the background of its long-run goals of price stability and sustainable economic growth and of the information currently available, the Committee believes the risks are weighted mainly toward conditions that may generate heightened inflation pressures in the foreseeable future...."

2004 DECEMBER

Decision to Expedite Release of Minutes.

"...the Committee unanimously decided to expedite the release of its minutes. Beginning with this meeting, the minutes of regularly scheduled meetings will be released three weeks after the date of the policy decision. The first set of expedited minutes will be released at 2 p.m. EST on January 4, 2005."

*Excerpts from press releases following selected FOMC Meetings

1990 RESERVE BANK OF NEW ZEALAND

Policy designed to keep future All Groups Consumer Price Index inflation outcomes between 1 and 3 percent on average over the "medium term." When conducting policy, the Bank is directed to "seek to avoid unnecessary instability in output, interest rates, and the exchange rate."

1991 BANK OF CANADA

An "inflation-control target range" for the 12-month change in total CPI inflation of 1 to 3 percent, with policy aimed at the 2 percent midpoint. Also, policy is directed to move inflation to the 2 percent midpoint over the next 6 to 8 quarters. Core inflation is used as a shorter-term operational guide for policy.

1992 BANK OF ENGLAND

A target of 2 percent measured by the 12-month change in the total CPI, with policy designed to bring inflation to target "in a reasonable period of time without creating undue instability in the economy."

1998 EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK

Target defined in terms of the year-on-year increase in the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices, with policy designed "to maintain inflation below, but close to, 2 percent over the medium term." Furthermore, "...without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ECB shall support the general economic policies in the Community with a view to contributing to the achievement of....a high level of employment and sustainable non-inflationary growth."

The Inflation Research Center (IRC) at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago analyzes issues related to the Fed's mandate of maintaining stable prices to help foster maximum sustainable economic growth.

Economists in the IRC use the latest statistical methodology and economic theory in research projects aimed at helping policymakers, including Chicago Fed President Michael Moskow, address practical problems they face formulating national monetary policy on the Federal Open Market Committee. The IRC also encourages policy-relevant research and fosters the dissemination of research findings through the academic and policy-making communities.

"The IRC fosters basic and applied research on monetary policy," said senior economist and economic adviser Jonas Fisher, who manages the Center's activities. "The center's economists develop tools for practical policy-making."

The IRC has focused on applying developments in time-series statistics to better measure inflationary pressures. The Chicago Fed National Activity Index (CFNAI) is a good example. The CFNAI is a monthly index that provides a summary measure of economic growth and an assessment of emerging price pressures. The index was developed and produced under the direction of the IRC and is based on recent academic research on inflation forecasting.

In addition to developing tools for inflation forecasting, IRC economists examine the determinants of real economic activity, productivity growth, inflationary expectations, and the design of optimal fiscal and monetary policy. The ultimate goal of this research is to gain a better understanding of the forces generating inflationary or deflationary pressures.

ONGOING AND NEW INITIATIVES

Numerous other efforts are underway, including:

- Developing a new model-based statistical measure of core inflationary impulses.

- Investigating how long-run relationships implied by economic theory can improve short-and medium-run forecasts of inflation and other economic variables.

- Examining the use of disaggregated price data to understand the process of price formation at the firm level.

The IRC also carried out a number of outreach efforts in 2005. Well-known experts on inflation and macroeconomic modeling visited the center to present their research and provide feedback on current and potential IRC projects. IRC economists also organized a conference on price stability in November attended by more than 80 leading academic macroeconomists and policymakers. The IRC has a Web site featuring working papers, research articles, and information about IRC conferences, data, and visitors.