The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago has a tradition of strong performance that continued in 2007, a year of leadership transition. I had the honor of succeeding retiring President and CEO Michael Moskow in September. Though I have been president for just over six months, I have been deeply involved in the monetary policy-making process for more than a decade. In fact, most of my research career has involved studying monetary policy decision-making and its effects on the economy. Since 1995, it has been my privilege to attend Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings — first as a senior staffer and since 2003 as the Bank's Research Director. I have been involved in the policy-making process during a variety of interesting economic and financial periods — experience that suits me well as we deal with current challenges.

The Federal Reserve is responsible for promoting sustainable economic growth, stable prices, maximum employment, and an efficient payment and financial system. The Chicago Fed represents the Seventh Federal Reserve District, a unique population center with significant agri-business, manufacturing, financial service and technology sectors. We work in the public interest, and our strategies and actions are aligned with the needs of our regional and national economy. As the challenges facing the economy become increasingly complex, it is essential that our policies and practices evolve to meet them. The leaders and staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago are the key element in dealing effectively with these challenges, and I am proud to lead such a talented and innovative group of people.

I am also pleased to be working with the many dedicated individuals who served in 2007 on our boards of directors in both Chicago and at our Detroit Branch. I greatly appreciate the counsel of these talented people and how generously they give of their time. In particular is the contribution of Miles White, the Chief Executive Officer at Abbott, who finished his service on the Chicago board after six years, including the last two as chairman.

As for the publication you are holding, this annual report recaps some important economic developments last year. It also features a discussion of financial markets in 2007 and looks at the Federal Reserve's role in responding to developments in these markets. In addition, the report includes a discussion with the leader of our team of researchers dedicated to the study of financial markets. It also looks at the resiliency of our many electronic access products, which contribute to the effective functioning of the financial system. I hope you find the report informative.

Charles L. Evans

President and Chief Executive Officer

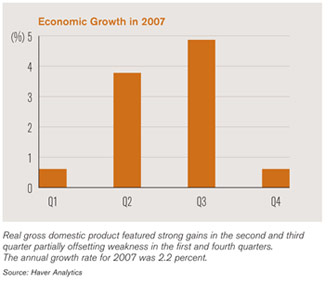

In 2007, the economy, as measured by the increase in real gross domestic product (GDP), grew at an annual rate of 2.2 percent. However, growth was spread unevenly over the year. It started slowly, picked up steam through mid-year, and then experienced weakness at the end of 2007.

Overall, economic growth in 2007 was somewhat below what the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago estimates as the economy's potential growth rate - that is, the rate of growth it can sustain over time given its labor and capital resources. The shortfall from potential in large part reflected a severe decline in residential construction, which reduced real GDP growth by an average of 0.9 percent point per quarter over the year. Solid rates of growth in business fixed investment and household consumption along with rising net exports offset some of the weakness due to the residential sector.

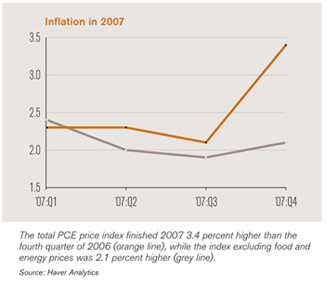

With growth just below potential, labor markets also began to ease in 2007. The unemployment rate rose from 4.4 percent in late 2006 to 4.8 percent in late 2007, and changed little, on balance, in early 2008. Still, the level of resource utilization remained elevated through much of the year, and increases in prices for food and energy and other commodities also put pressure on inflation. As a result, inflation was elevated last year. The price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) rose 3.4 percent over the four quarters of 2007. Core PCE, which excludes food and energy prices, increased 2.1 percent. Although this pace was down slightly from 2006, the improvement reflected developments early in the year, and core inflation rates were higher at the end of 2007 than they were at mid-year.

SECOND HALF OF 2007

The second half of 2007 was dominated by financial turmoil. As the residential housing market deteriorated, delinquencies and defaults on subprime mortgages increased substantially, jeopardizing the income flows supporting the many layers of securities that had been built upon them. As a result, market participants substantially reduced the perceived value of these instruments, as well as the value of other similar complex securities even if they contained no subprime-related debt. Uncertainty over collateral valuation and counterparty risk boosted the demand for liquidity. In addition, financial intermediaries had to take troubled assets back onto their balance sheets, reducing their willingness to issue new loans. These factors, along with increased concerns about the macroeconomic environment, resulted in a tightening of terms and costs of credit to some borrowers, thereby reducing their spending capacity. They also induced a sense of caution, which caused some households and firms to pull back on spending plans as they waited to see how events would transpire.

The second half of 2007 was dominated by financial turmoil. As the residential housing market deteriorated, delinquencies and defaults on subprime mortgages increased substantially, jeopardizing the income flows supporting the many layers of securities that had been built upon them. As a result, market participants substantially reduced the perceived value of these instruments, as well as the value of other similar complex securities even if they contained no subprime-related debt. Uncertainty over collateral valuation and counterparty risk boosted the demand for liquidity. In addition, financial intermediaries had to take troubled assets back onto their balance sheets, reducing their willingness to issue new loans. These factors, along with increased concerns about the macroeconomic environment, resulted in a tightening of terms and costs of credit to some borrowers, thereby reducing their spending capacity. They also induced a sense of caution, which caused some households and firms to pull back on spending plans as they waited to see how events would transpire.

Given the relatively high level of resource utilization in the first half of 2007, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) maintained the slightly restrictive stance it had established in late 2006, holding the target federal funds rate at 5-1/4 percent through August. In light of the developing financial turmoil, the FOMC began lowering the target federal funds rate in early September, bringing the rate to 4-1/4 percent by the end of 2007. As 2008 began, the financial turmoil intensified and the pace of economic growth slowed. With inflation expectations remaining contained, the FOMC then further lowered the target to 2.25 percent by mid-March.

Given the relatively high level of resource utilization in the first half of 2007, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) maintained the slightly restrictive stance it had established in late 2006, holding the target federal funds rate at 5-1/4 percent through August. In light of the developing financial turmoil, the FOMC began lowering the target federal funds rate in early September, bringing the rate to 4-1/4 percent by the end of 2007. As 2008 began, the financial turmoil intensified and the pace of economic growth slowed. With inflation expectations remaining contained, the FOMC then further lowered the target to 2.25 percent by mid-March.

MOVING FORWARD

For 2008 as a whole, it is expected that the economy will grow, but at a quite sluggish rate. Importantly, the adjustments in housing and financial markets likely will weigh on activity, particularly in the first half of the year. However, the current fed funds rate is accommodative; and, because monetary policy operates with a lag, the effects of recent rate cuts should promote growth as the year continues. Fiscal policy will also act as a stimulus. In addition, while not as robust as in the late 1990's and early this decade, the underlying trend in productivity remains solid, providing a sound base for production and income generation over the long term. Accordingly, growth is expected to improve later in 2008 and return to near potential in 2009.

Core inflation should gradually come down in 2008, as the economy operates below its potential level of output. Still, there is a risk that inflation could remain stubbornly high. A particular concern is that increases in food and energy and other commodity prices will be passed on to downstream customers. Persistent food and energy price increases could eventually find their way into inflation expectations. To date, inflation expectations appear to be contained; however, the longer total inflation runs above levels consistent with effective price stability, the greater the danger that inflation expectations will rise. Thus, these inflation developments will be carefully monitored.

Notes:

*This essay reflects information available as of March 21, 2008.

ECONOMIC RESEARCH

- In support of the Chicago Fed's monetary policy-making responsibilities, staff devoted considerable time to analyzing sharp declines in residential real estate markets, increases in subprime mortgage defaults, and related disruptions in credit and financial markets.

- Special policy briefings covered topics ranging from the structure of new auto industry labor contracts to the effect on forecasting models of changing inflation trends.

- Twenty-four working papers were produced, and 24 previously written papers were accepted for publication in scholarly journals. Of special note were an acceptance at the American Economic Review, two at the Journal of Political Economy, and three at the Review of Economic Studies.

- Economists also presented research analyzing a range of economic and policy developments in the Chicago Fed publications Economic Perspectives, Ag Letter and Chicago Fed Letter.

- In addition, Economic Research and the Consumer and Community Affairs staff worked together on a conference that brought together researchers and workforce development practitioners to discuss strategies for increasing the economic mobility of disadvantaged workers.

SUPERVISION AND REGULATION

- Supervision and Regulation needed to respond to the financial turmoil triggered by subprime mortgages as well as to rising numbers of problem banks, driven largely by deterioration of the auto industry in Michigan.

- With regard to financial turmoil, the department continued to monitor mortgage and commercial-real-estate lending as top risks, bolstered examiner training in the credit area, and closely analyzed the effects on District banks of the stressed market and liquidity environment.

- To address the rising number of problem banks, the department shifted staff resources and enhanced its monitoring of weaker banks. It also strengthened communication and coordination with other bank supervisors, especially those responsible for Michigan banks.

- More than 1050 examinations, inspections and off-site reviews were conducted.

- The department continued to improve its risk analytics by focusing on identification of fundamental (root) causes and the problem-bank resolution process.

- A number of new processes were implemented to increase the efficiency of examinations.

CENTRAL BANK SERVICES

- In response to pressures evident in short-term funding markets, the Board of Governors in December announced plans to establish a temporary Term Auction Facility (TAF) program to auction term funds to depository institutions. Central Bank Services facilitates these auctions for the Seventh District.

FINANCIAL MARKETS GROUP

- The Chicago Fed's Financial Markets Group provided multidisciplinary expertise in financial markets and the clearing and settlement operations that support them, with a particular focus on Chicago derivatives exchanges and clearinghouses.

FINANCIAL SERVICES

- The District Check operation was a System leader. The Des Moines office remained among the top performers, and the Midway office improved its efficiency, productivity, and quality.

- Seventh District sales of check-processing services played a vital role in supporting, selling and implementing Check 21 products.

- District Cash operations aggressively pursued efficiency improvements throughout the year. A process-improvement initiative was implemented in both the Chicago and Detroit offices, significantly improving high-speed machine utilization.

OTHER ACTIVITIES

- Charles L. Evans succeeded Michael H. Moskow as president and CEO.

- A record 27,814 people toured Chicago's Visitor Center.

- Teams from 35 high schools and 15 colleges took part in the High School and College-level Fed Challenge programs, and the Chicago Fed sponsored 10 economic teacher workshops.

- Executives from across the Federal Reserve System gathered in Chicago twice during the year for Senior Leadership Conferences.

- The District's Money Smart Week program expanded into Iowa and central Illinois and increased participation in existing programs in Chicago, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Approximately 1,000 partner organizations worked together to bring over 1,500 seminars, classes, and special events on personal finance topics to thousands of consumers.

CUSTOMER RELATIONS AND SUPPORT OFFICE

The Federal Reserve's national Customer Relations and Support Office is headquartered at the Chicago Fed.- The Customer Relations and Support Office (CRSO) exceeded National Account Program and System revenue targets and the Electronic Access cost recovery target.

- The CRSO redesigned its Web site, FRBservices.org, launching Check 21 interactive forms and a Federal Reserve Financial Services contact look-up tool called My FedDirectory. The site was developed in 2007 and unveiled in January of 2008.

- The CRSO successfully achieved 2007 goals for converting customers to an all IP Fedline connection environment by mid-2009.

PREVENTING MORTGAGE FORECLOSURES

Members of the Consumer and Community Affairs Department focused on the mortgage foreclosure crisis.Long active in this area, the department broadened its partnership with the Chicago-based Home Ownership Preservation Initiative (HOPI), co-hosting two meetings with representatives of banks, investment companies, mortgage service companies, and local government agencies.

These meetings led to the development of new strategies for loan work-out and counseling, agreements with servicers to incorporate loss-mitigation techniques, and plans to move foreclosed property more quickly to productive use. The lessons learned and strategies developed were shared throughout the Seventh Federal Reserve District through a series of conferences widely attended by industry leaders, community development practitioners and government officials. These meetings also identified other issues for consideration that are being addressed by additional working groups.

CONFERENCES CONTRIBUTE TO PUBLIC POLICY RESEARCH

Conferences remained integral to the development and dissemination of high-quality public policy research.Economic Research organized 16 conferences, some with co-sponsors such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the International Monetary Fund, the Upjohn Institute, and Chicago Metropolis 2020.

Topics covered included:

- The economic outlook.

- The mixing of banking and commerce.

- The implications of globalization for systemic risk to financial institutions.

- Mergers and acquisitions in the financial services industry.

- The changing structure of the U.S. auto industry.

- The evolution of the use of payment innovations to improve transportation networks.

- Developments in state business taxation.

- The impact of Medicaid on state budgets.

- Cost-effective carbon reduction.

Financial markets have been characterized by significant turmoil since the summer of 2007. Even as this annual report went to press in April of 2008, credit conditions remained tight, and market volatility continued to be high. These market disruptions raise many issues, but one of particular importance to the Federal Reserve System is the appropriate role of public policy in response. As the premier public policy institution for addressing financial stability issues in the U.S., the Fed must understand the underlying causes of financial disruption in order to design an appropriate policy response.

This article focuses on one such underlying cause of financial disruptions: innovation. This is a source of great benefit for our economy and our standard of living. But, like any sort of innovation, financial innovation can be disruptive. To quote Joseph Schumpeter, economies progress via a process of "creative destruction." Financial turmoil can be a way in which this sort of creative destruction works in the financial sector.

This article discusses recent market turmoil, looks at the role that financial innovation plays in such disruptions, and then explores why even highly beneficial innovations may be disruptive when first introduced. It concludes with some thoughts about the role of the Fed in responding to disruptions.

RECENT TURMOIL IN FINANCIAL MARKETS

Over the last fifteen years, financial markets have been characterized by a remarkable variety of innovative instruments and practices, including securitized cash flows, structured investment vehicles, and a veritable explosion of derivative contracts. These innovations not only enabled the creation of new financial products and opened up new sources of funding for businesses and consumers, but also directed these funds to a broader range of borrowers. Businesses and consumers who were previously unable to tap a wide range of funding sources gained access to credit at a lower cost. Financial institutions also benefited from these developments, increasing their fee-based income and overall profitability while economizing on expensive capital.

As we entered 2007, benign conditions generally prevailed. There was substantial liquidity in financial markets, and investors continued to place an unusually low price on risk. This state of affairs came to an end suddenly in the summer of 2007. In response to increased default rates on subprime mortgages, risk avoidance rose sharply, and market participants reduced their perceived value of all financial instruments with subprime exposure.

In addition, market participants started to question the value of other securities. This could be seen in the market for asset-backed commercial paper-known as ABCP-where rates soared even for paper supported by assets unrelated to subprime mortgages. Many ABCP issuers and other borrowers had to turn to very short-term financing, as lenders were unwilling to commit funds at normal terms because of uncertainty over collateral valuation and other counterparty risks. Moreover, there were periods in August when markets in certain debt instruments virtually disappeared. Without actual market transactions, it became difficult to assess the fair value of the more complex securities.

THE LINK BETWEEN FINANCIAL INNOVATION AND FINANCIAL TURMOIL

Economic history has much to teach us about financial crises. Banking panics were common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Panic of 1907 was particularly severe and ultimately led to the establishment of the Federal Reserve System six years later. More recent episodes include the Penn Central commercial paper default in 1970, the stock market crash of 1987, and the disruption associated with the Russian default in 1998.

Each of these episodes, as well as the recent turmoil, had unique features. But there is an important common element to them: In each case, the event was associated with a drying up of liquidity. The most liquid assets are those that can be immediately used to discharge indebtedness: cash, bank reserves, and the like. When liquidity is said to "dry up," market participants find it increasingly difficult to convert otherwise sound assets into these more liquid media of exchange. This would be the case if lenders are unwilling to accept the illiquid assets as collateral, if dealers in these assets substantially widen bid-ask spreads, or if transactions in these securities simply cease to occur.

Why do periods of financial stress occur periodically, and why is liquidity an integral part of these events? Surprisingly, innovation in financial markets can play an important role. Continuous innovation is one of the key strengths of our economy. Financial innovation enhances markets' ability to allocate capital and risk. But during periods of rapid financial innovation, it can take time for market participants to learn how these innovative instruments and practices operate, especially in the event of falling asset prices.

To elaborate on this theme a bit, think about a financial innovation, say, the development of some new type of derivative contract introduced at a time when markets are expanding. The innovation performs well and becomes widely used, and market participants look at this record of success when designing risk-management systems. Now suppose that something happens to stress the market. The new contract may interact with market forces in ways that are largely unexpected. The strategies that market participants had used to quantify and manage risk may not adequately encompass the events and interactions now taking place, making these risk-management strategies inadequate to address the unexpected developments. A natural response may be to pull back, conserve liquidity, and curtail trading in risky markets until a clearer picture of the level of risk emerges. If market participants were to withdraw from risk-taking in this way en masse, the result would be a liquidity crisis. Interestingly, a body of academic research exists that explores precisely this process: That when investors can't quantify a particular type of risk, they may respond by avoiding that risk entirely.1

Recent financial events seem to fit this narrative in many ways. The innovation behind the recent difficulties relates to the widespread use of the originate-to-distribute business model, in which mortgages are funded by selling them bundled together in highly structured securities. Of course, mortgages have been securitized for many years, but there are two features of this business model that are relatively new and that are particularly important for the current situation. The first is the extension of the originate-to-distribute model to subprime mortgages. Subprime mortgages represented only 8.5 percent of the mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) issued in 2000. By the end of 2006, this fraction had increased to 20 percent.

The second feature is the increasing use of multiple layers of structure. For example, a mortgage originator may sell a portfolio of mortgages to an intermediary, who in turn divides up the cash flow into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) of different risk tranches. These CDOs can be sold directly or can be combined with other securities to back instruments such as ABCP, and so on. In all, there may be numerous layers of structure between the original mortgage loans and the ultimate providers of funds.

The benefit of this complex structuring is that it accommodates different levels of risk tolerance on the part of different investors, thus tapping a wider range of funding sources. However, these multiple layers of structure can be extremely opaque, making it more difficult for the ultimate providers of funds to assess the true level of risk they are taking on.

These innovations in structured housing finance had never been tested in a period of widespread weakness in housing markets. But with the recent declines in housing prices, these structured securities have behaved quite differently than they did during better times. For example, many investors appeared to have assumed that the triple-A tranche of a sub-prime MBS would act like a triple-A corporate bond, which carries little default risk and low downgrade risk. We now know that these highly rated MBSs have a risk profile rather different from a comparably rated corporate obligation. The rating of an MBS is less certain than that of a corporate bond, so MBSs have much greater downgrade risk. In addition, most of the default risk of a corporate bond is idiosyncratic to the firm, so it can be readily diversified away by investors. In contrast, a security backed by a diverse pool of mortgages has little idiosyncratic risk. Most of the risk in these securities is due to common systematic factors, such as the general movements in home prices. This sort of risk is considerably more problematic for investors than idiosyncratic risk, because it can't be diversified away.

These characteristics of MBSs were unanticipated during the quiescent period before the summer of 2007, but they became apparent during the ensuing turmoil. We saw abrupt and unexpectedly large ratings downgrades of triple-A-rated MBSs and other collateralized mortgage debt obligations, with ratings declines of ten notches or more not uncommon. The perceived downside risk of these securities increased in a highly correlated fashion, as would be expected for securities sharing the same systematic risk factors. Many market participants started calling into question the safety of securities that had received high scores from the ratings agencies. For example, even the so-called super-senior tranches of CDOs, thought to be extremely well insulated from losses, were shunned by investors. These investors also began to shun other types of structured securities, even those completely free of mortgage-related collateral.

An important factor influencing these developments was the complexity of the structured credit products used to finance mortgages. This complexity made it difficult and costly for the ultimate investors to learn about the underwriting standards being applied to the original mortgages. There were few defaults during the long period of rising home prices, and investors paid little attention to the growing evidence of lax underwriting, such as high loan-to-value ratios, negative amortization, and deficient documentation. But when housing markets weakened, the consequences became apparent. Default rates on subprime loans rose far beyond those anticipated by the risk-management models commonly in use.

History provides us with other examples of linkages between financial innovations and liquidity crises, and there are some interesting common elements between them and the current situation.2 Consider the unexpected bankruptcy in 1970 of Penn Central, a major railroad that was an important issuer of commercial paper. The Friday before its collapse, Penn Central was seen to be in financial trouble, but the company was expected to receive a government loan guarantee that would keep it afloat. Over the weekend, it became evident that no government support was forthcoming, and Penn Central declared bankruptcy. Investors woke up Monday morning with commercial paper that was essentially worthless. Penn Central's failure raised doubts about the integrity of the commercial paper market in general. A predictable flight to quality ensued: Treasury yields declined, and corporate debt yields rose.

The financial innovation in the Penn Central example was the use of commercial paper to substitute for bank loans. Commercial paper had become an important source of funds for large firms in the 1960s, but risk-management systems for commercial paper remained untested until the recession of 1969-70. The Penn Central bankruptcy was a rude awakening that these systems were inadequate.

The stock market crash of October 19, 1987, may also be associated with financial innovation. While there is no universally accepted explanation for the sharp drop, a widely held theory focuses on the innovation of portfolio insurance.3 Portfolio insurance is a form of computerized dynamic hedging that can involve automatic selling after certain market declines. Portfolio insurance implicitly relies on the availability of market liquidity-that is, the ability to sell shares at the prevailing price-when the automatic selling kicks in. Prior to October 1987, this innovation seemed to work well. But on October 19, liquidity was grossly inadequate. It appears that computerized selling into the declining market turned the morning's losses into a wholesale rout that was completely unforeseen by existing risk-management models. As with the Penn Central episode, a flight to quality followed, with Treasury yields falling dramatically.

A third example is the market crisis in the fall of 1998 that was triggered by the Russian bond default. This shock caused bond spreads to widen in both emerging and developed countries, and induced a major liquidity crisis. The financial innovation that magnified this shock was the growth of highly leveraged and opaque hedge funds, notably Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). The possibility that failing hedge funds would respond to falling market prices with a fire sale of available assets led intermediaries to withdraw liquidity from the market and reinforced the initial shock.

In each of these cases, markets eventually learned from the crises. This resulted in improved approaches to risk management that could address the new types of market risks. The commercial paper default of Mercury Financing in 1997 was much larger than Penn Central, yet caused virtually no disruption to the markets. Similarly, the 6 percent fall in stock prices that occurred on October 13, 1989, had nowhere near the impact of the market break two years earlier. Finally, the failure of the Amaranth hedge fund in 2006 was twice the size of LTCM's failure, yet this default was absorbed by the markets without turmoil. And market participants undoubtedly will learn important lessons from the turmoil of 2007 and 2008 that will improve their structure and functioning in the future.

THE ROLE OF THE FED IN RESPONSE TO FINANCIAL DISRUPTIONS

Ultimately, financial market participants have the strongest incentives to sort things out when a liquidity crisis hits. However, the Fed and other public policy institutions play an important role in monitoring and facilitating efficient market functioning. The Federal Reserve seeks to foster policies that mitigate the possible fallout from the financial market to the broader macroeconomy. This means that our policy should account for how events might affect the attainment of monetary policy objectives, which are to facilitate financial conditions that help the economy obtain both maximum sustainable growth and price stability.

The Fed has a number of tools at its disposal. First, through its authority as a bank supervisor, the Fed sets regulatory standards aimed at fostering the safety and soundness of the banking system. This process serves an important role during times of turmoil because well-capitalized banks can act as shock absorbers for financial markets. Second, the Fed operates Fedwire, which is one of the key large-value payment systems supporting financial markets. Periods of financial stress tend to be associated with spikes in payments volume, so ensuring that interbank payments are made in a safe, reliable, and timely fashion removes a potential source of uncertainty (see related story). Third, the Federal Reserve Banks do major work to mitigate the impact of financial turmoil in the community. During the subprime disruption the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago has worked closely with lenders, community leaders, and government officials to assist borrowers confronting foreclosures. In particular, we have strongly supported and contributed to the Home Ownership Preservation Initiative (HOPI). HOPI was originated and launched at our Reserve Bank in 2003, and is a partnership of Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago, the City of Chicago, and the Fed (see related story). It works with all areas of the mortgage lending business, from Wall Street to Main Street, to reduce the number and impact of foreclosures in Chicago, and provides a model for service to the community that is adaptable to other areas of the country.

Our most powerful tool for addressing a liquidity crisis is monetary policy. In setting the stance of monetary policy, the Fed has a dual mandate: to help foster maximum employment and price stability. Monetary policy is concerned with mitigating financial market stress to the extent that the stress impedes fulfillment of this dual mandate. Broadly speaking, our response to a financial shock is similar to the way we respond to other shocks to the economy. First, we consider the most likely effects of the shock on the future paths for economic activity and inflation. Second, we take a risk-management approach to policy. This means we consider less likely, but more costly, alternative outcomes that we may want to insure against. We then may adjust the stance of policy to guard against the risk of events that may have low probability but, if they did occur, would present an especially notable threat to sustainable growth or price stability. In this way we set policy to best fulfill our dual mandate.

With regard to shocks to the financial system, the risks we must guard against concern the ability of financial markets to carry out their core functions of efficiently allocating capital to its most productive uses and allocating risk to those market participants most willing to bear that risk. Well-functioning financial markets perform these tasks by discovering the valuations consistent with investors' thinking about the fundamental risks and returns to various assets. A widespread shortfall in liquidity could cause assets to trade at prices that do not reflect these fundamental valuations, impairing the ability of the market mechanism to efficiently allocate capital and risk. Furthermore, reduced availability of credit could reduce both business investment and the purchases of consumer durables and housing by creditworthy households.

We clearly must be vigilant about these risks to economic growth. However, overly accommodative liquidity provision could endanger price stability, which is the second component of the dual mandate. After all, inflation is a monetary phenomenon. Indeed, one of the many reasons for the Fed's commitment to low and stable inflation is that inflation itself can destabilize financial markets. For example, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, high and variable inflation contributed to large fluctuations in both nominal and real interest rates.

The Fed has kept these various risks to growth and inflation in mind when responding to the financial turmoil that started in August of 2007. We have taken a number of monetary policy actions to insure against the risk of costly contagion from financial markets to the real economy. Our response to the onset of the turmoil focused on ensuring that the financial markets had adequate liquidity. For example, on August 10, the Fed injected $38 billion in reserves via open market trading. In one sense, this was a routine action to inject sufficient reserves to maintain the target federal funds rate, which at that time was 5-1/4 percent. The nonroutine part was the size of the injection required to do so (the largest such injection since the days following September 11, 2001). On August 16, with conditions having deteriorated further, the Federal Reserve Board, in consultation with the District Reserve Banks, moved to improve the functioning of money markets by cutting the discount rate by 50 basis points and extending the allowable term for discount window loans to 30 days. The Board also reiterated the Fed's policy that high-quality ABCP is acceptable collateral for borrowing at the discount window.

At its regular meeting on September 18, the FOMC cut the federal funds rate 50 basis points, the first in a series of rate cuts that brought the target funds rate to 2.25 percent by mid-March of 2008. This target funds rate was a full 300 basis points below the level that prevailed at the onset of the financial turmoil. In addition, the Fed inaugurated a new Term Auction Facility (TAF) that allocates Federal Reserve credit via an auction mechanism. The TAF allows banks to borrow for a longer term than the usual discount window practice, and the auction mechanism can deliver an interest rate for these term loans that is below the posted discount rate. It appears that the $140 billion provided by the TAF in December of 2007 through February of 2008 was useful in alleviating funding pressures around the start of 2008.

As the turmoil continued through the first three months of 2008, the Fed undertook several initiatives to help provide liquidity to stressed markets. On March 7, the Fed announced an expansion of the TAF, increasing the size of the two March auctions to $50 billion each. That same day, the Fed announced its intention to conduct a series of term repurchase (RP) transactions with primary dealers totaling $100 billion. These RPs could be collateralized by a variety of securities, including Treasury debt, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities. On March 11, the Fed increased its existing dollar swap lines with the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank. And on March 16, the Fed increased the maximum maturity of primary credit loans to 90 days from 30 days.

Two other policy innovations in mid-March are particularly noteworthy, in that they expanded liquidity provision to institutions other than commercial banks. First, on March 11 the Fed announced a new Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF). Under the TSLF, the Fed can lend up to $200 billion of Treasury securities to primary dealers for a term of 28 days, collateralized by assets that include both agency and AAA-rated private-label mortgage-backed securities. Second, on March 16 the Fed created a lending facility that extends overnight credit directly to primary dealers. These loans can be collateralized by a broad range of investment-grade debt securities. Since the primary dealers are nondepository institutions, these loans required the Fed to invoke its authority to lend to nonbanks under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Under this act, such lending is only permissible under "unusual and exigent circumstances." Such loans are the first extensions of credit by the Federal Reserve to nondepository institutions since the 1930s.

Together, these policy actions expand the Fed's role of providing liquidity in exchange for sound but illiquid securities. While these actions represent major innovations in Fed practice, they are in the spirit of the oldest traditions of central banking. As described by Walter Bagehot in his 1873 treatise Lombard Street, the job of the central bank is to "lend freely, against good collateral" whenever there is a shortage of liquidity in markets. These actions by the Fed will provide support to financial markets and to the economy as a whole during this period of turmoil.

But we certainly cannot rule out the possibility of continued market difficulties. We cannot be sure how long it will take for financial intermediaries to complete the process of re-evaluating the risks in their portfolios and restructuring their balance sheets accordingly. Moreover, further mortgage defaults due to declines in house prices and the fact that many sub-prime adjustable rate mortgages will see their rates rise over the next few months could have negative feedbacks onto housing and financial markets. Furthermore, there remains a good deal of uncertainty about the creditworthiness of many key market participants.

Given these risks going forward, the Fed must be diligent in applying the risk-management approach to policy formulation, in order to ensure that the economy is well cushioned against financial turmoil that seems to be an occasional concomitant to the beneficial process of financial innovation.

Senior Vice President David Marshall, head of the Chicago Fed's Financial Markets Group, contributed to the development of this essay. It is derived from a speech given by Charles Evans in Chicago in late November of 2007. The opinions expressed herein represent the opinions of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Open Market Committee or the Federal Reserve System. The essay was strongly influenced by the ideas of Riccardo Caballero and Arvind Krishnamurthy. (See R. Caballero and A. Krishnamurthy, 2008, "Collective Risk Management in a Flight to Quality Episode," forthcoming, Journal of Finance.)

Notes:

1See I. Gilboa and D. Schmeidler, 1989, "Maxmin expected utility with non-unique prior," Journal of Mathematical Economics, Vol. 18, No. 2, April, pp. 141-153; L. Hansen and T. Sargent, 2003, "Robust control of forward-looking models," Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 50, No. 3, April, pp. 581-604; and R. Caballero and A. Krishnamurthy, 2008, "Collective risk management in a flight to quality episode," forthcoming, Journal of Finance.

2For a further discussion of these examples, see Caballero and Krishnamurthy, op. cit.

3See G. Gennotte and H. Leland, 1990, "Market liquidity, hedging, and crashes," American Economic Review, Vol. 80, No. 5, December, pp. 999-1021.

In 2006, the Chicago Fed created a special group to study the behavior of financial markets. Members include researchers with backgrounds in economics, law, financial regulation and financial market operations. They look at a wide range of issues related to financial markets, and they also examine the clearing, settlement and large-value payment operations that support the markets-with a focus on Chicago derivatives exchanges and clearinghouses. In a Q&A, Senior Vice President David Marshall discusses the group's work.

Q. Is the Chicago Fed's interest in financial market policy motivated by recent market disturbances?

A. The turmoil that has characterized financial markets since August of 2007 certainly illustrates why financial market expertise is vital to the public policy process. But it's important to remember that financial turmoil is hardly a new phenomenon. There have been four major financial crises in the last 28 years-the 1980 crisis involving Mexico's default, the market crash in October of 1987, the liquidity crisis following the Russian default and devaluation in the fall of 1998, and the September 11 terrorist attacks. We've also identified 35 potential market disruptions over the last 25 years that could well have materialized into full-blown crises. Each one had the potential to adversely affect economic activity, with a real impact on people's standard of living. Clearly, it's imperative that we better understand the dynamics of these disruptions to have a better chance of avoiding them-and to mitigate their impact when they do occur.

Q. What is the Fed's role when financial crises occur?

A. The Fed has a critical role. While each crisis may look very different from the preceding crisis, one thing they all have in common is a shortfall of liquidity. In other words, many otherwise sound institutions can't obtain the means to make needed payments. This is where the Fed comes in. The Fed is the ultimate source of liquidity in the economy because the liabilities of the Fed (currency and bank reserves) constitute the key means of payment. So when there is a shortage of liquidity, the Fed is generally called upon as first responder. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 said one of the key reasons for establishing the Fed was the need for an "elastic currency." This means the Fed is expected to add or withdraw liquidity as needed to facilitate economic activity.

Q. Why is it important for the Chicago Fed to have a Financial Markets Group?

A. There is a contribution to be made by looking at financial market policy issues from a Chicago perspective. Chicago is the second most important center of financial activity in the U.S., behind New York. But Chicago's role in finance is not simply to act as a miniature New York. Rather, Chicago is the global leader in a small but important slice of the financial pie: exchange-traded derivative contracts (mostly futures and options). The total volume of derivative contracts traded on Chicago's exchanges last year vastly exceeded the volumes traded on exchanges in any other global financial center. Most is traded on the Chicago Board Options Exchange and on the exchanges now affiliated with CME Group (a newly formed combination of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade). But there are a number of small and nascent derivatives exchanges based in Chicago that add to the vibrancy of the Chicago financial markets, including the Chicago Climate Exchange (a venue for trading carbon emission permits), OneChicago (a venue for trading single-stock futures), the United States Futures Exchange, the Merchants Exchange, and the Actuarial Exchange.

Q. Are there policy concerns particularly relevant to derivatives exchanges and clearinghouses as opposed to financial activities such as banking or securities trading?

A. Certain characteristics of derivatives trading are particularly noteworthy. For example, derivatives trading and clearing require high-frequency risk and liquidity management to ensure the continued creditworthiness of market participants. They depend on reliable execution of time-critical margin payments on a daily and sometimes twice-daily basis. Much of the trading on these exchanges is done via direct computer-to-computer connections (so called "black box" trading), with trade execution times on the order of microseconds. The liquidity in these markets resides, to a large extent, with relatively small proprietary trading firms whose structure and incentives are very different from the large banks and brokerage houses that dominate securities trading. Given these special characteristics, it is important that financial market policy analysis be informed by a Chicago point of view. The Chicago Fed's Financial Markets Group seeks to provide this perspective.

Q. What does the future hold for the city of Chicago's financial markets?

A. Derivatives markets represent a rapidly growing segment of the financial sector. Over the last eight years, the total value of derivatives contracts outstanding has grown by over 20 percent per year. Each year, it seems that new types of derivative contracts are created and traded. Just look at the phenomenal growth of credit derivatives over the past five years. So Chicago, as the world's center of derivatives exchange activity, is well positioned to benefit from this growth trend. But remember that while Chicago has the lion's share of exchange-traded derivatives activity, this represents only 15 percent of the derivatives market. The remaining 85 percent of derivatives trading is in the over-the-counter market based in New York and London. And the over-the-counter market is looking more and more exchange-like, with high-liquidity, screen-based trading, and even central clearing. So the big question for Chicago is how successfully Chicago's institutions will meet the challenge of an increasingly innovative over-the-counter market. We don't know how all this will play out, but I feel confident that the ultimate winner from this competition will be the U.S. economy.

With spikes in payment volume often prevalent in times of economic stress, the Federal Reserve strives to ensure that payments can be made in a secure, reliable and timely fashion. Removing uncertainty about the payment system gives confidence to financial institutions and results in more stable and efficient markets.

A stable and healthy U.S. payments system depends on providing financial institutions with secure, reliable access to Fedwire®, FedACH® and Check 21 Services. By operating several channels that provide electronic access to these services, the Customer Relations and Support Office (CRSO) at the Chicago Fed helps support an efficient payment system.

The ongoing evolution of the Federal Reserve's FedLine® access channels helps to provide greater usability through enhanced operating speed, efficiency, security and reliability, which in turn help foster secure and stable operations for the nation's payment system. These channels are designed to help support stable, efficient payment operations for the smallest to the largest financial institution.

The Federal Reserve is continuously seeking ways to incorporate contemporary technologies into its offerings in order to help financial institutions better manage their payments business, and has introduced two such large-scale upgrades to IP-based technologies. In recent years, the CRSO has also led the migration of more than 7,000 financial institutions to the new systems.

In 2006, the CRSO completed the migration of customers from the now-retired DOS-based FedLine® platform to the Web-based FedLine Advantage® access solution. The focus has now shifted to managing the migration of computer-to-computer interface customers to an IP-based solution called FedLine Direct®. This solution plays a critical part in the day-to-day operations of high-volume financial institutions.

CUSTOMERS APPRECIATE SUPPORT DURING CONVERSION

Both of these recent efforts to migrate to IP-based technologies have helped position the Federal Reserve as a leader in innovative technology offerings that meet financial institutions' needs for reliable and secure payment operations. The U.S. Postal Service and Agribank were among the first to migrate to the FedLine Direct access solution and realize the benefits of the Federal Reserve's next-generation technology.

The U.S. Postal Service uses the Federal Reserve's FedACH Services to handle an average of 2.5 million ACH transactions per month for payroll and other payments to its approximately 700,000 employees. Its high transaction volume made the U.S. Postal Service a natural candidate to complete its migration to FedLine Direct as soon as it became available.

Streamlined technical support and maintenance are key benefits for financial institutions as they migrate to FedLine Direct, said Richard Kotenberg, project manager in the U.S. Postal Service's Data Transfer group.

"It allows us to upgrade to take advantage of current technology," he explained. "There's more flexibility in this type of solution."

The U.S. Postal Service's IP-based FedLine Direct connection has been up and running since the third quarter of 2006.

One of the first financial institutions to use FedLine Direct to conduct Fedwire Funds transactions was AgriBank, a unique institution cooperatively owned by 18 regional farm credit associations in 15 states. AgriBank facilitates wholesale loans and other financial services to promote agriculture and agribusiness.

Because FedLine Direct was designed to integrate with financial institutions' existing systems, the migration resulted in almost no changes to AgriBank's daily operations. Now that the migration is complete, AgriBank uses FedLine Direct to process an average of 8,500 wire transfers per month.

IMPROVING THE CAPABILITIES OF A VARIETY OF PRODUCTS

Innovative technology is not the only area in which the Federal Reserve receives high marks from financial institutions. Customer satisfaction surveys show financial institutions appreciate the Federal Reserve's efforts to develop and deploy contemporary technology to improve the capabilities and benefits of FedACH, Fedwire Funds, Check and FedCash Services, Account Management Information (AMI) and FedLine Advantage.

In addition, being able to continue operations during emergency situations is one of the most important aspects of the support provided to financial institutions. The Federal Reserve maintains business continuity plans to address possible operational threats and has undertaken rigorous contingency planning and testing to help ensure resiliency.

The Federal Reserve also provides advice and direction to financial institutions to help ensure they have plans in place to help maintain the flow of electronic payments. Recommended contingency arrangements include back-up personnel, alternate Internet Service Provider (ISP) and access connection setup, and substitute network components and arrangements.

These efforts and others help to contribute to an efficient payment system, which in turn helps to support well-functioning financial markets. Helping make both resilient and effective will drive the efforts of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and the CRSO in the coming year and well into the future.