A Conversation with Austan Goolsbee About the Economic Impact of Covid-19

The Chicago Fed hosted the Seventh Annual Summit on Regional Competitiveness during the week of November 16, 2020. The virtual event kicked off with a conversation about the impact of Covid-19 on the economy between Anna Paulson, director of economic research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and Austan Goolsbee, the Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Here is their conversation. It has been edited for clarity, and some figures and references have been included.

Anna Paulson: Can we start by getting your take on the general state of the economy?

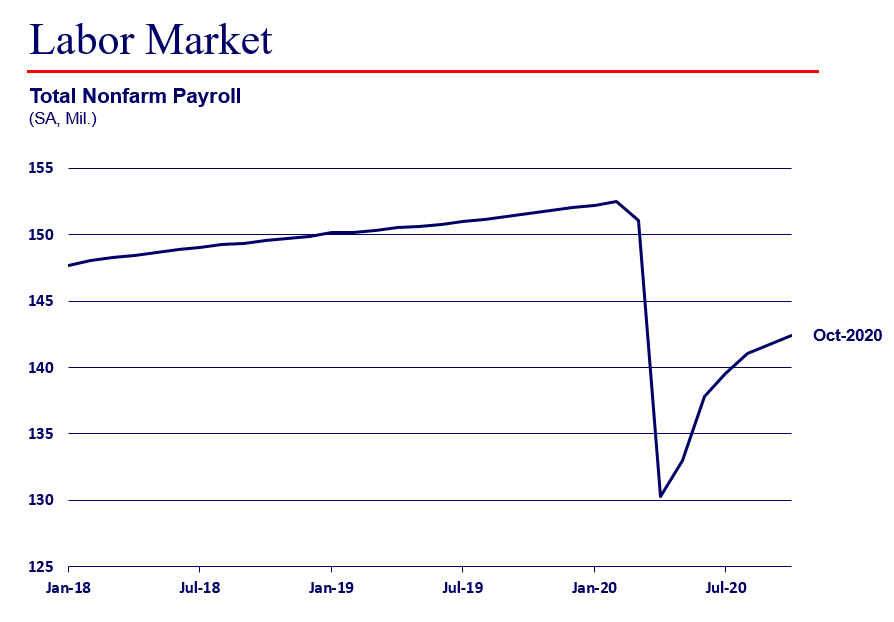

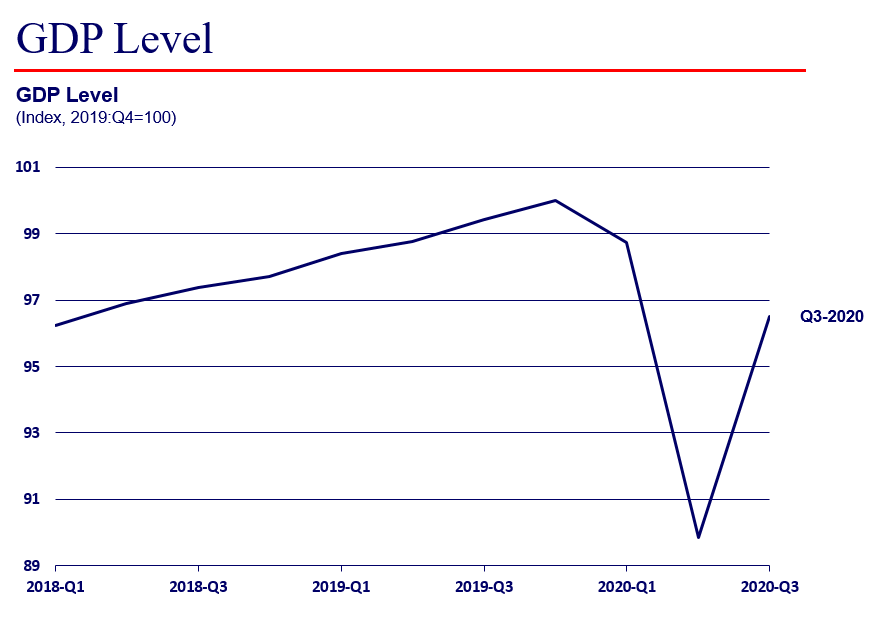

Austan Goolsbee: The economy is in the deepest downturn we have ever had, even worse than 1932, the worst year of the Great Depression. However, it has snapped back faster than we ever snapped back, but only about half or two thirds of the initial decline (shown in figures 1 and 2). On the one hand, we haven’t had to follow the normal rules of a recovery; in a normal rebound the unemployment rate only comes down about 1.5 points a year. Given that we lost 21 million jobs in a month, if we had to follow the normal rules, it would be eight to ten years before we got back from this. So it’s been great that we have had a faster—unprecedented—rebound. But it wasn’t enough—not even close. If this third wave is as bad as it looks so far, especially as it looks in our region, I’m really quite nervous what that would mean for the economy.

1. Non-farm payroll (January 2018–October 2020)

2. Gross Domestic Product (2018:Q1–2020:Q3, indexed relative to 2019:Q4)

Research from the Chicago Fed1 and a paper I have with a colleague2 were some of the first research exploring the link between the virus and economic conditions. This work shows that the recovery is tied very closely to the progression of the virus. There is no tradeoff between the virus and the economy, in my opinion.

Paulson: As you mentioned, your research and some of the research from the Chicago Fed suggests that it is personal choice that drives a lot of the decline in economic activity and not so much stay-at-home orders and other policy directives. What does that mean for policymakers?

Goolsbee: Well, I don’t think it was lockdown orders that shut down the economy. If we look at the evidence, we can see that it was people staying at home because they didn’t want to get sick. For our paper we looked at (anonymized) phone records for visits to 2.25 million businesses, using consumer visits as a measure of business activity. Beginning in March, you see a collapse of consumer visits to these businesses. For our research, we wanted to look within metro areas where there were different shutdown timings, to see the consumer response. We looked across the whole country—I think there were 502 counties where there was a border on either sides of a policy divide. If you look in the same week, in the same metro area, you would see activity decline by 70%, with the lockdown orders accounting for about one-tenth of that. For example, visits to beauty salons in Bettendorf, IA, where there was no lockdown order, decline by almost the identical amount as they do across the border in Illinois where there is a lockdown order. So it really is not about the lockdown order, it’s about people getting scared. In the counties where the death rate starts to rise, people stop going out to businesses of all different forms because they are afraid of the disease. So, what that tells us now is that if the virus starts really spreading again, it could seriously undermine consumer activity. The only way that it wouldn’t occur is if people are so fatigued by the disease that they no longer care about the risks.

Paulson: What does that mean for policymakers as they contemplate a rising case load?

Goolsbee: I always say, “The virus is the boss,” which means the most important thing you can do for the economy is to slow the rate of spread of the virus. So, policymakers have got to take every action they can to slow the rate of spread of the virus. The irony is that you don’t need the vaccine in order to do that. Places like Taiwan, Korea, Australia, and New Zealand got control of the virus through public health measures and they’re basically back (to pre-pandemic economic levels). I wish we could put a direct focus on the public health aspect. The CARES Act is a relief bill—not a stimulus bill, as it is often referred to. It was designed to avoid permanent economic damage from what is supposed to be a temporary shock. The thing about relief bills is that they are expensive. It is analogous to burning money so we do not freeze while the furnace is out. It works, but only as long as you are feeding it money. We need to understand that a trillion dollars every six to nine months is the run rate of life support for the biggest economy in the world. So, if the policymakers do not put the focus on slowing the rate of the virus, we’re going to have to pay a lot more in the form of rescue and relief.

Paulson: We focus a lot on the government sector and what official policymakers can do, but what about the private sector? Are there things that businesses, nonprofits, and other private sector actors can to do influence behavior?

Goolsbee: I think so. When the polio vaccine was introduced, there was a lot of fear and uncertainty about taking it. To dispel this anxiety, Elvis got the polio vaccine on national television. Apparently, that in itself increased the immunization rate by 30 percentage points. People said, “Well if Elvis got it … it must be ok!” In a world where everything is so politicized and partisan, I do feel like the private and nonprofit sectors have credibility. Obviously, the vaccine and medical companies have a role in creating credibility, but I think big, reputable organizations taking actions for themselves is also important. The more organizations model good behaviors and the more they reward their employees for it, the better. For example, we should pay more attention to things that may in the short term erode GDP—paid sick leave, that is, paying people to not come to work—but that in the longer run are better than people coming to work when sick and contributing to the spread of the virus. This does not mean you have to engage in partisan politics, it’s just modelling compliance behavior. I think that would be helpful here.

Paulson: Are there lessons from your research about the individual fear of getting infected that might give us some ideas about how businesses ought to behave?

Goolsbee: If you are running a business and you are trying to draw a conclusion from my research or the Chicago Fed’s research about what you should do, I think that would be to make your customers feel safe. If you’re a physical business and your customers don’t feel safe, they’re not going to come back. In our data, we were able to look at different sizes of companies and different activity levels in a store. We observed a decided shift as the pandemic raged in an area away from busier stores to less busy stores. There is a parallel with the 2008 crisis: As that crisis began, as a financial crisis, people withdrew from the financial system and that was a disaster. Here, it’s a physical contagion and people withdrawing from the physical, service sector economy. Until now those sectors have largely been recession proof. So we don’t know how to respond. We never anticipated that health care spending or education spending would plunge in a recession. These are the sectors that usually keep chugging along in a recession.

Paulson: So, this has been a theme throughout this conversation but I would like to hit it explicitly: What do statements like “the virus is in charge” mean to you and how has that altered your thinking? What might’ve been different if we had really accepted the premise that “the virus is in charge” from the very outset?

Goolsbee: The most successful places took protective measures like wearing masks and instituting widespread testing from the start. There is an argument in the U.S. that the people who are most at risk should be the ones to withdraw and that we should not impose on the freedoms of the people who do not feel they are at risk. According to this line of thinking, if you have a pre-existing condition, if you’re old, or are otherwise at risk, you should stay home and let others go about their normal life. And the problem with that, to my mind, is if you take people who are over 65, clinically obese, have diabetes or asthma or heart disease or an autoimmune disease, or are on chemo, even taking out the overlap, more than the majority of the country classifies as one of those at risk categories. To me it’s not a viable strategy to say, let’s have the majority of the country stay home. The fundamental thing is that people have to feel if they go out of their house, they’re not going to get sick. Other countries, Australia and New Zealand for example, have a high degree of personal freedom, but still did very heavy testing. With that amount of testing, they were able to see an increase and stomp it out right away, with a quite strict lockdown. So, according to the epidemiologists, if policymakers had moved quickly and competently more than 100,000 deaths could have been prevented. That’s heartbreaking. And that’s just the deaths, to say nothing about people who are not going to see their families for the holidays, people who are not going to school, the countless other difficult situations that could’ve been prevented.

Paulson: As you look forward, even as the progression of the virus is uncertain, what are the various recovery scenarios? What kind of things do you think are likely to be temporary and what are likely to be more permanent?

Goolsbee: This is the first recession we have ever had that had nothing to do with the economy. It’s more like a natural disaster, like a hurricane came ashore or we had an earthquake. The economy wants to come back. If the vaccine was available now and everyone could get it, I think the economy could go right back to where it was before this began. I can’t help but remember that period right before the 2008 financial crisis. A shocking number of the most damaging loans were made in the last six months before things fell apart. I feel like if we could’ve just stopped what we were doing six months earlier, the financial crisis would’ve been so much less severe. And I kind of feel that way now. We’ve got to stop this surge here. We can’t let this spiral out of control in the last six months. Otherwise half of the deaths are going to end up being in this last period.

On your other point about what is permanent versus temporary, I am skeptical that anything that has happened in the last six months because of Covid is going to reverse some long-standing trend. However, I’m receptive to the idea that Covid has accelerated long-standing trends. For example, over the last 15+ years there has been a huge shift to internet commerce and that has accelerated during this downturn. I think that is going to be permanent. Once this is done, a lot of people are going to have developed a habit for buying groceries on line, for example. So, the implications of that for commercial real estate, for brick and mortar retailers I think are pretty serious.

On the other side, I’m more skeptical of these stories that speculate that major metros, like New York or Chicago or Minneapolis, are going to die. Or that Milwaukee is in trouble because everybody is trying to move away from cities to rural and smaller metro areas. That type of shift would reverse a 180-year trend in the United States. I think once this is done, we are going to rediscover why that trend existed in the first place: that productivity is a lot higher when we are together. There might be a little less business travel—going to conventions and that kind of thing—but I think this Regional Summit is going to be in person when you go forward, because we are going to rediscover that the productivity spillovers are bigger when they’re actually agglomerating in the same place. I think that will come back.

Notes

1 Diane Alexander and Ezra Karger, 2020, “Do stay-at-home orders cause people to stay at home? Effects of stay-at-home orders on consumer behavior,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, working paper, No. 2020-12, available online; and Diane Alexander, Ezra Karger, and Amanda McFarland, 2020, “Measuring the relationship between business reopenings, Covid-19, and consumer behavior,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Chicago Fed Letter, No. 445, available online.

2 Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson, 2020, “Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline,” June 19, University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, working paper, No. 2020-80, available at SSRN or Crossref.