What Happened to Subprime Auto Loans During the Covid-19 Pandemic?

At the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, subprime auto loans appeared to be particularly vulnerable to credit quality deterioration potentially arising from pandemic-related economic hardships. For one thing, the delinquency rate on subprime auto loans had risen to a fairly high level in the years leading up to 2020, signaling that many borrowers were already under financial stress when the pandemic began. In addition, unlike other consumer loan categories, such as federal student loans or some residential mortgages, no new laws required lenders to provide forbearance to auto loan borrowers.

In this post, we review how subprime auto loan borrowers nevertheless largely avoided delinquency during the pandemic. Though not required by law to do so, auto lenders still widely offered forbearance to borrowers early on. In addition, many states imposed temporary moratoriums on vehicle repossessions. These actions, in combination with the fiscal support that households received, appear to have successfully suppressed delinquencies and repossessions.

Data

To analyze auto loans during the pandemic, we use monthly data on individual auto loans that are collateral for Asset Backed Securities (ABS)—i.e., loans that lenders fund by issuing bonds to investors rather than, for example, using bank deposits. Loan-level data from auto ABS are provided to the public through ABS-EE filings required by the Securities and Exchange Commission for certain types of ABS. We compile a database including all auto loans from any auto ABS with available data, and restrict the data in two ways: loans that were outstanding as of January 2020 and loans that were part of ABS issues that reported data for every month in 2020.

The advantage of these data is that they are publicly available and they provide information on two key events that other data sets may not record: forbearance and repossession. The downside is that the data are not likely to be representative—these ABS issues represent only about 6% of the auto market, and ABS issuers deliberately select loans so that the portfolio underlying a given ABS issue can be expected to yield a targeted risk and return distribution.

Altogether, the ABS database we have assembled comprises a panel that included about seven million loans per month at the beginning of 2020. The sample size decreases over time and dips below six million by the end of 2020 and to about 4.5 million by April 2021. Loans exit the sample for various reasons, including being paid off in full or charged off after default.

The data include a substantial amount of subprime loans, totaling about 1.2 million loans a month at the beginning of the sample, using a definition of subprime as a FICO score below 620.1 The ABS securitizers with the most subprime loans in the data are Ally, Americredit, Carmax, Santander Consumer USA, and World Omni.

Forbearance

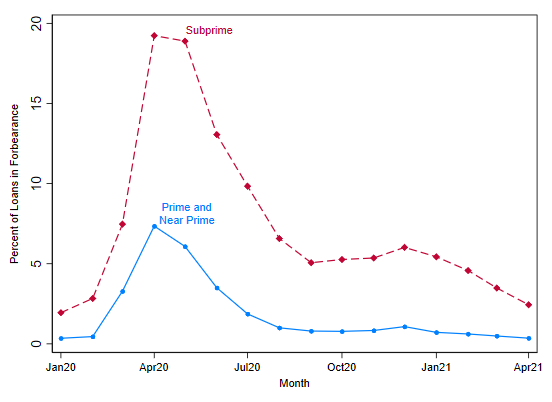

Starting in late March 2020, lenders granted forbearance to borrowers across a variety of household and business loans. In the consumer auto loan sector, forbearance agreements peaked quickly in April and May (see figure 1), when approval of forbearance was nearly automatic at many lenders. Since then forbearance take-up has fallen to much lower levels, though the decline has been uneven and the level of forbearance is still higher than before the pandemic, particularly for subprime loans.

Figure 1: Forbearance take-up was substantial

A typical forbearance agreement in the auto ABS data allowed a borrower to skip from one to four months of payments, making up those payments at the end of their loan and effectively shifting the stream of required payments forward in time. Two months was the most common duration of forbearance. Many lenders allowed borrowers to receive more than one round of forbearance, though the additional rounds of forbearance tended to come with stricter qualification criteria than the initial round from March to May, when approval of forbearance was closer to automatic.

Delinquencies

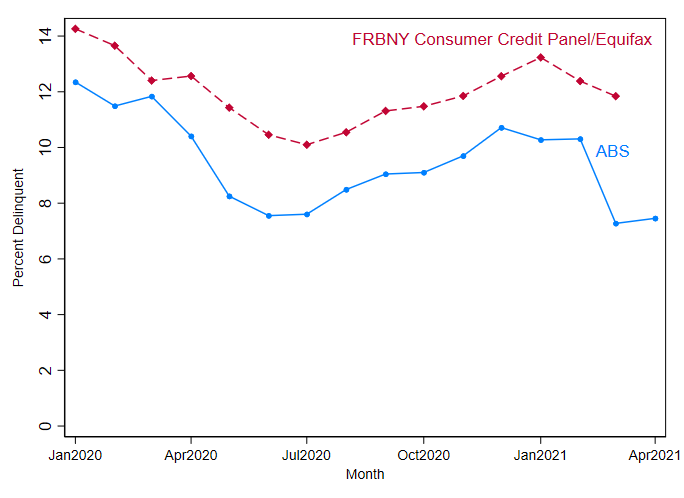

Aggregate data show that delinquencies decreased substantially in the late spring and summer of 2020 when forbearance was widespread. Figure 2 displays the delinquency rates on subprime auto loans in the ABS data and, for comparison, also displays the delinquency rate on the sample of subprime auto loans contained in the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax Data. The differences in the levels of delinquency rates across the two series reflect the differences between the ABS loans and the universe of auto loans in the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax data, and also perhaps the differences that arise from using the FICO score in the ABS data and the Equifax Risk Score in the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax data.

Figure 2: Percentage of subprime loans 30+ days delinquent

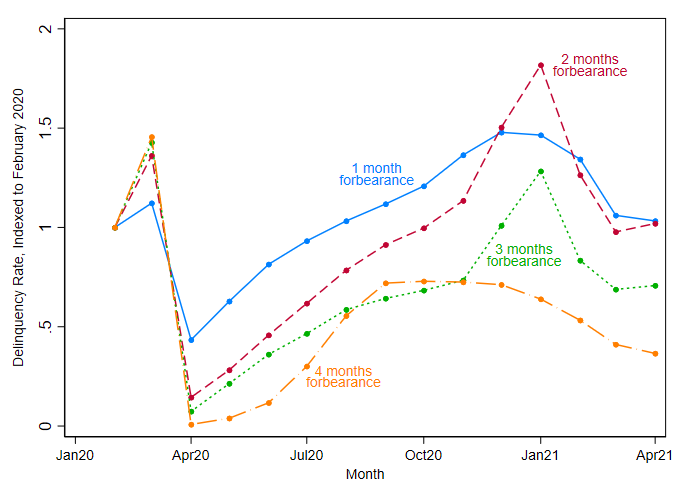

To understand the relationship between forbearance and delinquency a bit more precisely, we look at the delinquency rate over time (figure 3) depending on the duration of forbearance received in April 2020. Loans that received longer durations of forbearance show commensurately longer-lasting declines in their delinquency rates. For example, loans that received one month of forbearance in April 2020 experienced the fastest rebound in delinquency rates. This graph also shows a spike in delinquency rates in March 2020 among this set of loans that received forbearance in April, an indication of the need for forbearance due to the economic hardships that many households experienced at the onset of the pandemic, before receiving much fiscal support.

Figure 3: Longer forbearance durations led to longer-lasting declines in delinquency rates

The variation in the duration of forbearance is largely driven by lenders choosing different default amounts of forbearance that they granted to all of their borrowers, rather than by borrower choice. While borrowers may differ systematically across lenders, the effect we see here is largely mechanical, since delinquency is typically reset once a borrower is in forbearance. As a result, what we are capturing is essentially the decision by lenders to mechanically suppress delinquencies with the aim of providing borrowers time to receive fiscal support during the pandemic.

Repossessions

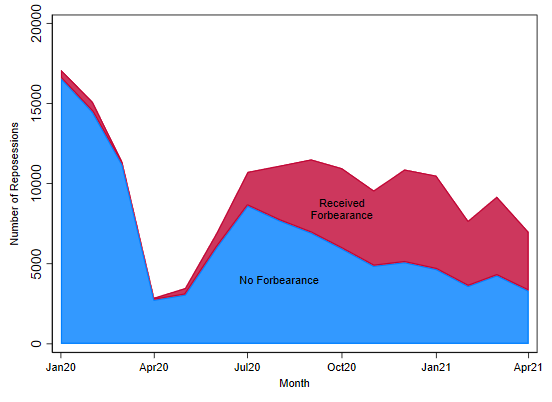

Repossessions on auto loans fell in mid-2020, reflecting pandemic-driven lockdowns that restricted vehicle repossessions (on the basis that repossessions were not an essential activity) and also reflecting that many borrowers were able to avoid default through either forbearance or fiscal support. That said, repossessions rebounded in the late summer, and as shown in figure 4, many of the underlying loans had received forbearance earlier that year. This is an indication of rising economic hardship at the end of 2020, as forbearance was no longer widely available and as the support provided by the fiscal stimulus from the previous spring began to fade away.

Figure 4: Repossessions increasingly consist of loans previously in forbearance

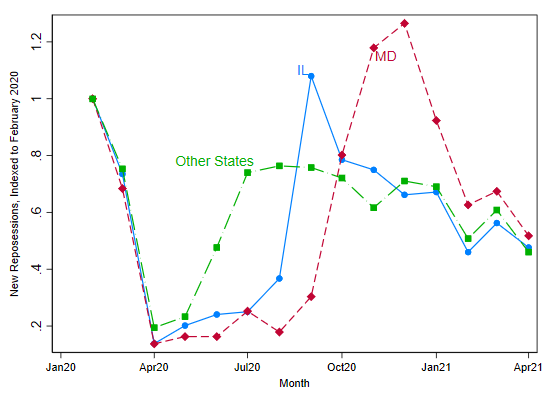

Some states imposed moratoriums on repossessions in recognition of the hardships imposed by the pandemic. Figure 5 captures the impact of these state-level moratoriums in the ABS data. Illinois and Maryland were the second-to-last and last states, respectively, to lift their moratoriums. In all other states combined, repossessions increased substantially by July 2020, but this increase was delayed by a few months in Illinois (which lifted its moratorium in late August 2020) and another month or so in Maryland (which lifted its moratorium in October). These later spikes in Illinois and Maryland suggest that the moratoriums effectively held down some latent repossession activity that might have occurred otherwise, much like forbearance agreements appear to have lowered delinquencies earlier in the year.

Figure 5: Lifting of repossession moratoriums led to temporary spikes in repossessions

Conclusion

Most auto lenders made forbearance widely available in the spring of 2020, according to data from auto ABS. Nearly one in five subprime auto borrowers in these data availed themselves of forbearance. As a result of this forbearance and other fiscal support for households, delinquency rates on auto loans fell significantly during the summer of 2020. Auto lenders significantly rolled back the availability of forbearance during the summer, after which delinquencies rebounded but still remained at or below pre-pandemic levels. Similarly, the overall volume of repossessions has rebounded but has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels, even as repossessions are increasingly affecting borrowers who received forbearance early in the pandemic. The overall picture is one in which the combination of forbearance, repossession moratoriums, and fiscal support from the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan Act appear to have significantly helped subprime auto borrowers to avoid more adverse outcomes during the pandemic.

Note

1 We use the FICO score at origination, obtained from the ABS Auto Database.