Pittsburgh: A Detroiter’s Perspective

For Detroit or any Rust Belt city looking to revitalize its urban core, Pittsburgh is often brought up as a model to follow. Before World War II, Pittsburgh was well known for the black clouds of soot that often hovered over its downtown area. (Given its industrial legacy, it has been dubbed “the Steel City.” ) But more recently, it has been deemed America’s most livable city six times by three different publications since 2000.1 According to Scott Bricker of Bike Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh is the fourth most active walking/biking city in the United States. Bike Pittsburgh and other civic-minded organizations and stakeholders have been the key to Pittsburgh’s turnaround. They are united by a mission to make their city thrive.

On June 18–19, 2015, the Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Richmond sponsored a policy summit on housing, human capital, and inequality in Pittsburgh. This summit gave me not only a chance to experience Pittsburgh for myself, but also an opportunity to hear from some of the people whose efforts have steered the city in a positive direction. In this blog entry, I will share my thoughts on my visit to Pittsburgh and some observations on how Pittsburgh is and is not a model Detroit can follow in its revitalization efforts.

Background

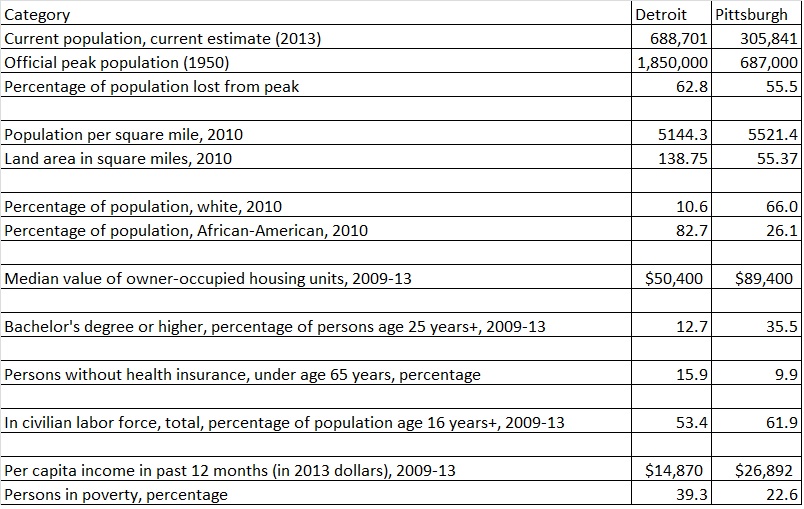

In preparation for my trip, I did a statistical comparison of Detroit and Pittsburgh. The table below displays the similarities and differences I found most interesting.

Table 1

From the table, it’s clear that both cities lost a similar percentage of their respective populations after peaking in 1950. While both cities’ population densities are similar, the size of Detroit’s land mass stands out: Detroit is more than twice the size of Pittsburgh. When adding up the size of each of Detroit’s vacant land parcels, it amounts to 40 square miles—almost 30% of Detroit’s land area, but almost 75% of Pittsburgh’s!2 Another major difference between the two cities is their racial composition: Pittsburgh’s population today is predominantly white, whereas Detroit’s shifted from mostly white to mostly African-American.

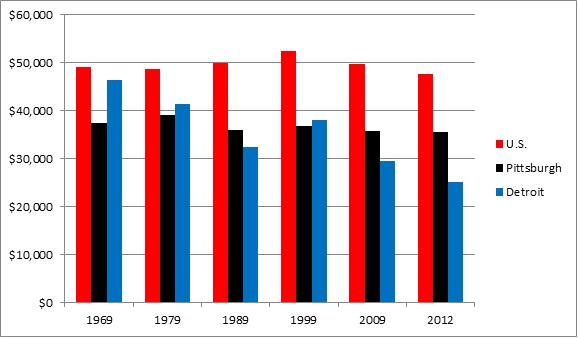

The other statistics in the table depict a higher standard of living in Pittsburgh versus Detroit. A higher percentage of Pittsburgh’s population has a bachelor’s degree, participate in the labor force and possess health insurance. Not surprisingly, per capita incomes are higher and poverty rates lower in Pittsburgh than in Detroit. The chart below shows how median household incomes have steadied and slightly rebounded in Pittsburgh versus the continued decline in Detroit.

Median Household Income: United States and Central Cities of Pittsburgh and Detroit, Select Years

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data from SOCDS (1969, ’79, ’89, and ’99) and the U.S. Census Bureau (2009, 2012); U.S. Census Bureau data adjusted using the CPI Inflation Calculator.

When looking at the chart, keep in mind that the city of Pittsburgh lost population in this time frame, yet incomes have started to record positive gains in recent years. So even if the city of Detroit were to continue to lose population, positive income gains in the future are attainable as seen in Pittsburgh.

East Liberty

My business trip to Pittsburgh began by taking one of its rapid buses3 to the neighborhood of East Liberty, located within the East End of Pittsburgh. According to Rob Stephany, director of community and economic development, The Heinz Endowments, East Liberty was Pennsylvania’s third busiest commercial corridor until World War II (only behind the downtowns of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh). However, activity decreased after World War II as consumers headed out to suburban shopping centers to do their shopping. To try and revitalize East Liberty, Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority decided to make the neighborhood’s center more walkable by transforming much of its outer surface streets into a one-way ring road where visitors could park and then walk to nearby shops. Developers hoped that this plan would also spawn development along the ring road. Unfortunately, the ring road deterred further commercial development and prompted businesses to close and residents to leave. The only major development projects along the ring road were large, multifamily apartment towers.In the late 1990s, then-mayor of Pittsburgh, Tom Murphy, noticed the relatively poor condition of the East Liberty neighborhood when compared with wealthier neighborhoods Highland Park to the north and Shadyside to the south. Mayor Murphy’s recruitment of Home Depot to the neighborhood along with the creation of a new mixed-income housing development helped lead to East Liberty Development, Inc.’s (ELDI) 1999 community plan, which outlined the community’s vision for the neighborhood.4 In subsequent years, Whole Foods and Target moved into East Liberty, the apartment towers were torn down, an old Nabisco factory was transformed into lofts and office space (where a unit of Google does business), and East Liberty came to symbolize how Pittsburgh has changed recently.

Because I took a rapid bus, my ride to East Liberty from downtown Pittsburgh only took ten minutes. The quick buses have contributed to East Liberty’s renaissance by providing residents fairly easy access to their respective places of employment while improving the neighborhood’s connections with the rest of the city. When I disembarked from the bus, I couldn’t help but notice the large development project taking place at the transit station. When completed, the East Liberty rapid bus transit station will include a retail/residential complex that will allow easier access to the neighborhood from the station.5 The development of new residential units in East Liberty has made it a trendy place to live, driving up home values and rents. Unfortunately, recent development has made it more difficult for some lifelong residents to remain in the neighborhood.6

As I left the transit station and entered the core area of East Liberty, I was struck by the contrasts in the types of businesses and development. Across from the transit station stood the new Target, but as I walked down Penn Ave. away from Target, I encountered a mix of new construction along with blighted storefronts. A similar mix of buildings greeted me when I turned north on Highland Ave., which is also home to the iconic East Liberty Presbyterian Church that dominates the core area’s landscape. East Liberty was truly diverse in that within blocks, I saw signs of a neighborhood on the rise, including trendy restaurants and boutique hotels, while symbols of struggle—such as run-down apartments, check cashing outlets and discount stores—remained. This dichotomy reminded me greatly of Detroit.

Redefining Pittsburgh

During the summit’s panel on redefining Pittsburgh, Bill Flanagan, chief corporate relations officer, Allegheny Conference on Community Development, said that city leaders and stakeholders looking to revitalize their cities must learn to listen, must craft public policy with much forethought, and must be patient because civic engineering takes time to implement. Leaders and stakeholders in East Liberty have learned those lessons, as evidenced by their increasingly providing opportunities for lifelong residents to stay in the neighborhood, thanks to more mixed-income, affordable housing projects. Kendall Pelling, director of land recycling, East Liberty Development, Inc., shared how ELDI is buying up vacant properties, as well as properties home to crime, in order to lower crime rates and make East Liberty an even more attractive place to live. In the Larimer neighborhood, which borders East Liberty’s east side, assisting lifelong residents in their effort to stay was a central piece of their neighborhood development plan. It seems safe to say that leaders in Pittsburgh are following their own advice, especially the listening part.

In a separate panel, Bill Peduto, mayor, City of Pittsburgh, shared some of the policies and programs he’s participated in or promoted during his tenure on the Pittsburgh City Council and now as the mayor. Mayor Peduto’s comments focused on social mobility and neighborhood investment. Mayor Peduto argued the most important factors to social mobility are the chance to earn a quality education and the ability to get to work. According to Peduto, another avenue for greater social mobility is his policy in granting tax increment financing (TIFs)7 to developers. Mayor Peduto said his administration only grants TIFs if developers agree to pay their workers prevailing wages. Moreover, the Mayor said he sees a lack of investment in a particular neighborhood as sending a negative message to its residents. As a way to circumvent that potential problem, Mayor Peduto shared that his office assists in writing each neighborhood’s master development plan.

Pittsburgh: A Model for Detroit?

It’s easy to draw a comparison between Pittsburgh and Detroit because both cities saw a majority of their respective fortunes rise and fall with labor-intensive durable goods manufacturing industries. The cities’ and industries’ heydays came in the first half of the twentieth century. To the common observer, it may seem that Pittsburgh’s turnaround happened rather quickly and therefore is attainable for Detroit.

What the common observer may not realize is the forethought and diligence Pittsburgh leaders and stakeholders had regarding their city’s future. In the 1940s, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development—along with David Lawrence, then-mayor of Pittsburgh, and Andrew Mellon, the well-known banker and industrialist—started planning and implementing their idea for Pittsburgh’s future.8

In contrast, Detroit has lagged behind other cities in its revitalization efforts. For example, the Detroit Riverwalk Conservancy was formed in 2003 to help make the Detroit Riverfront more visitor-friendly. Impressed by what the Allegheny Conference did in Pittsburgh, the Greater Baltimore Committee began implementing its plan to improve Baltimore’s downtown in the 1950s, which eventually encompassed the city’s Inner Harbor in the 1960s.9 The planning of Chicago’s Lakefront Trail provides an even starker contrast with the city planning for Detroit. Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago included plans for a continuous lakefront park with a trail that became the Chicago Lakefront Trail, which was resurfaced in 1979.10 Detroit unveiled its most recent plan, the Detroit Future City plan, in 2010. This plan is the latest attempt at envisioning the path forward for Detroit. Will the Detroit Future City plan come to fruition? Time will tell if it matches the results already realized in places like Pittsburgh.

Bill Flanagan’s advice for cities and their stakeholders most definitely applies to Detroit, especially the two pertaining to listening and public policy. I associate listening in a Detroit context with regional collaboration—which Detroit and its neighbors have improved upon in recent years. For example, regional authorities were created for entities such as Cobo Hall (our convention center), and regional leaders came up with the “grand bargain,”11 which helped lift Detroit out of bankruptcy (and save the Detroit Institute of Arts’ collection). More regional collaboration will be needed for other solutions, especially public transportation, which has the potential to increase labor mobility and help better match employers with employees. With regard to public policy, Detroit must continue to improve its delivery of police and fire service in order to ensure the safety of its citizens.

The importance of social mobility and neighborhood investment that Mayor Peduto underscored at the summit is shared by Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, as demonstrated in his 2015 state of the city address.12 The magnitude of Detroit’s turnaround will be determined by how far it can reach outside of Detroit’s Downtown and Midtown neighborhoods and into other areas of the city. Just as in Pittsburgh, a strong correlation between neighborhood investment and neighborhood condition exists in Detroit. Mayor Duggan has looked to increase neighborhood investment through programs such as the Detroit Blight Task Force and Detroit Land Bank. One of Detroit’s challenges is to better coordinate activity between city government and city neighborhoods as Pittsburgh has done. Mayor Duggan is in the middle of implementing his neighborhood plan, which included the creation of a Department of Neighborhoods, placing neighborhood managers within each City Council District.13 Plans to improve social mobility, which in Detroit means reforming Detroit Public Schools have been presented by a task force and Michigan Governor Rick Snyder.

Conclusion

Detroit faces the same obstacles Pittsburgh faced and continues to face, though the magnitude of those obstacles appears larger in Detroit. Most of the obstacles will require greater collaboration among community developers, city leaders, and regional stakeholders so that as many Detroiters as possible can experience the city’s rebound. In many ways Pittsburgh’s redevelopment can serve as a model for Detroit’s, but in other ways it cannot. When the Pittsburgh model doesn’t apply to Detroit, Detroit can look to other cities for ideas. Arguably, the biggest take-aways from the policy summit were the many different plans and strategies other cities have executed that are available to help cities such as Detroit return to prosperity.Footnotes

1 Those publications are The Economist, Forbes, and Places Rated Almanac. More information is available online.

2 More information is available online.

3 More information is available online.

4 More information is available online.

5 More information is available online

6 More information is available online.

7 TIF is a financial mechanism used by municipalities and other governments to promote economic (re)development. TIF is intended to generate economic (re)development activity that would not otherwise occur. It works by establishing a specifically defined district, using incremental growth in revenues over a frozen baseline amount to pay for (re)development costs. TIF may utilize property, sales, or utility tax revenues.

8 See p.3 of "Downtown Pittsburgh: Renaissance and Renewal."

9 More information is available online.

10 More information is available online.

11 More information is available online.

12 More information is available online.

13 More information is available online.