Higher Education Faces a Perfect Storm During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Over the past decade or so, higher education in the U.S. has faced three major disruptive factors—declining public funding, declining enrollments, and the rise of online instruction. The Covid-19 pandemic has only magnified these challenges, creating a perfect storm situation for many universities and colleges across the nation. Here, I discuss each of these three key factors chiefly in the context of public higher education in the state of Michigan.

Declining public funding

The responsibility of paying for college has long been an issue. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration made significant changes to federal government student loan programs. In a televised address, President Reagan stated that ”education is the principal responsibility of local school systems, teachers, parents, citizen boards and state governments.”1 From his perspective, the proliferation of federal programs over the past 20 years had weakened local control of higher education. Since the 1980s, there’s been a debate on the role of the federal government in financing higher education. For example, funding for federal Pell Grants—which are generally given to undergraduates who demonstrate exceptional financial need—peaked in 2010, but by 2017, they had declined by 26%.2

In recent decades, Michigan’s public universities have seen the combined federal and state investment in higher education wane. As a result, the costs for postsecondary education have been shifted to the universities themselves and then to students and their families, leading some students to make difficult decisions about how to pay for college or whether to attend at all. To cover the shortfall in public funding, universities were forced to increase their tuition and fees beyond the normal rate of inflation. Using data from the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency, I calculated that in fiscal year (FY) 2001–02, tuition and fee revenue accounted for 46.8% of total revenue for Michigan’s public universities; by FY2018–19, however, the share of total revenue for Michigan’s public universities that came from tuition and fees had jumped to 71.7%. So, students with limited resources (or their families) were forced to borrow much more money in the late 2010s than in early 2000s to pay for college. Put another way, higher education in Michigan has changed from its post-World War II status of being publicly supported to being much more privately supported.

According to data from the Federal Reserve’s consumer credit report, student loans outstanding have increased 32% in the past five years, reaching $1.7 trillion, or about 40% of total outstanding consumer credit, in 2020:Q1.3 In addition, the New York Fed’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for 2020:Q1 shows that student loan debt now makes up a larger portion of total consumer debt than credit card debt, auto loans, and other types of loans (unlike in the early 2000s); today student loan debt is surpassed only by mortgage debt. Rising student loan debt may have contributed to students and their families relying more on the economic value proposition of a postsecondary education to make their decisions about college (rather than on other considerations such as opportunities for personal growth or avenues to contribute to society upon graduation, but without high financial compensation). In other words, students and their families may be feeling pressured to analyze how much they will earn after graduation versus the cost of a college education.

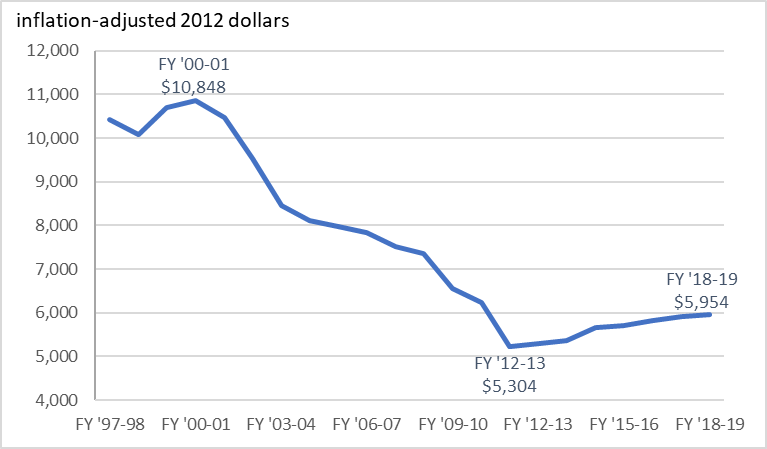

This decision process has been made increasingly difficult given the ongoing cuts to funding to public universities. Figure 1 shows the State of Michigan’s budgeted funding from FY1997–98 through FY2018–19 per full-year equivalent student (FYES)4 in inflation-adjusted 2012 dollars (using the Consumer Price Index). State funding for public universities in Michigan peaked in FY2000–01, at $10,848 per FYES, and declined to $5,304 in FY2012–13, before again rising slightly to $5,954 in FY2018–19. This implies that Michigan’s public universities have seen a decline in funding per FYES of over 45% in the past two decades in real terms. These funding cuts have forced Michigan’s public universities to make some difficult choices of their own to cover the costs of providing a high-quality education to their students. The Covid-19 pandemic will make state funding for Michigan’s public universities even more constrained in the coming years, as the State of Michigan’s general fund (which has accounted for about 74% of the total public higher education budget over the past five years5) is expected to face a shortfall of $2.5 to $3.2 billion during the current fiscal year.6

Figure 1. State of Michigan’s funding for public universities per full-year equivalent student

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency.

Declining enrollments

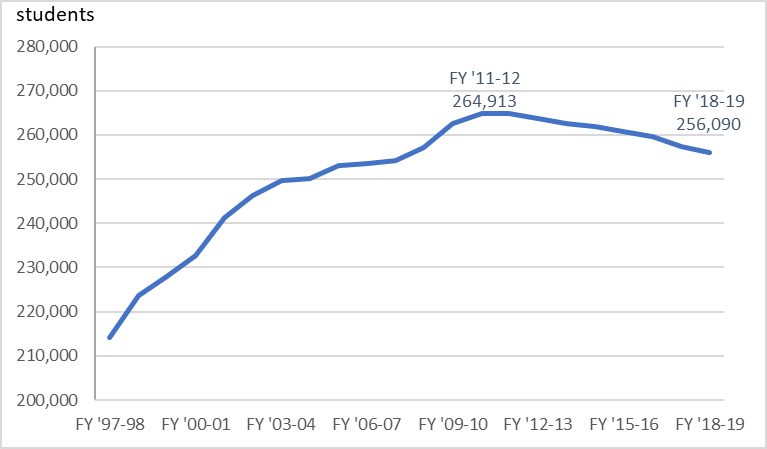

At the same time, demographic changes such as a decreasing birth rate and an aging population have resulted in declining enrollments at several Michigan public universities. The reductions in applications and enrollments have had an added impact on the amount of funding many of Michigan’s 15 public universities can receive, given that public funding is tied to FYES enrollments each year. Figure 2 shows how FYES enrollments continued to grow from FY1997–98 through FY2011–12 (even as state and federal funding for Michigan’s public universities generally fell over this span), but then enrollments began to decrease.

Figure 2. Michigan public universities’ budgeted enrollments of full-year equivalent students

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency.

Since FY2012–13, state funding per FYES in Michigan has increased slightly (see figure 1), but declining enrollments have limited the amount of state funding schools can receive. This means that Michigan’s 15 public universities are now competing with private universities and other public schools for a larger share of a shrinking pie within Michigan. Some Michigan public universities have been faring better than others at attracting students despite the overall downward trend in enrollments at these schools. Table 1 shows the percent change in FYES enrollments between FY2011–12 and FY2018–19 for each of Michigan’s 15 public universities. The changes range from an increase of 11.1% for the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor to a decrease of 27.7% for Lake Superior State University.

Table 1. Percent change in Michigan public universities’ full-year equivalent student enrollments between fiscal years 2011–12 and 2018–19

| Central Michigan University | –16.9 |

|---|---|

| Eastern Michigan University | –17.7 |

| Ferris State University | –11.9 |

| Grand Valley State University | 0.4 |

| Lake Superior State University | –27.7 |

| Michigan State University | 3.4 |

| Michigan Technological University | 4.3 |

| Northern Michigan University | –21 |

| Oakland University | 6.3 |

| Saginaw Valley State University | –19.2 |

| University of Michigan–Ann Arbor | 11.1 |

| University of Michigan–Dearborn | 7.4 |

| University of Michigan–Flint | –9.6 |

| Wayne State University | –4.3 |

| Western Michigan University | –11.8 |

| Total for Michigan's 15 public universities | –3.3 |

To make themselves stand out, schools in Michigan and elsewhere have adopted various ways of meeting students’ increasingly high expectations through improved amenities, including on-campus coffee shops and new technologies in classrooms. College sports such as football and basketball can also be used to attract more students. Successful college sports programs, such as those at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor and Michigan State University, can help promote universities locally and nationally; moreover, they can also help to boost alumni engagement with—and donations to—the university. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has created a tremendous amount of uncertainty about whether games will even be played and, if they are played, whether there will be fans in the seats (at some schools, season ticket holders account for a substantial amount of revenue generation that helps pays for these programs).

Declining enrollments are a problem not only at the undergraduate level, but also at the graduate level at universities across the nation. Before the pandemic, business schools throughout the country reported declines in enrollments in recent years. For instance, in an October 2019 Wall Street Journal article, it was reported that because of changes in U.S. immigration laws, American business schools had seen a sharp decline in applications from international students last year; according to the Graduate Management Admission Council, applications to U.S. business schools fell 13.7% in 2019 compared with the previous year, whereas Canadian and European business schools saw increases in applications, indicating a loss in competitiveness for American business schools.7 This is an important development because many U.S. universities have recruited foreign students to apply to their business schools and other programs, given that they typically pay higher tuition than their U.S. counterparts. More recently, Purdue University, located in West Lafayette, Indiana, announced it would pause its Master of Business Administration program and not enroll any business school students for the 2021–22 academic year; its graduate business school enrollments have fallen 70% since 2009, and the dean of the business school stated it costs more money to recruit candidates than the amount of revenue generated by tuition.8

The rise of online instruction

Rising demand among students for online postsecondary instruction over the past two decades has contributed to the proliferation of for-profit institutions that are geared primarily to distance learning—such as the University of Phoenix.9 Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, traditional universities had increased their online instruction offerings to help broaden their base of potential student candidates and to better compete with these newer for-profit schools. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 35.3% of college students across all levels (undergraduate and post-baccalaureate) were enrolled in some type of online learning classes in the fall of 2018, with 16.6% of the students taking online courses exclusively. So, as the pandemic continues to unfold, one of the key questions for higher education is this: Without the experience of engaging in face-to-face learning, living on campus, and participating in co-curricular and extracurricular activities (such as student clubs and sports), will prospective students still be attracted to a traditional university? If so, at what price? One irony here is that as the pandemic forces more traditional schools to use online curriculums to protect the health and well-being of their students and faculty members, some students may come to view distance learning from the newer institutions as the preferred alternative to what they’ll receive from a traditional university.

Conclusion

Three disruptive factors—declining public funding, declining enrollments, and the rise of online learning—have combined to make running a traditional university more challenging during the past decade or so, and the Covid-19 pandemic has only made this more difficult. It’s true that not all of Michigan’s universities are experiencing the same enrollment problems during this perfect storm, but it is becoming harder to justify running some school programs because competition for students also has increased the overall cost of recruiting them.

While some public universities will fare better than others, I think it is reasonable to assume that when this perfect storm finally subsides, the landscape of higher education in Michigan—and in many other states—will look significantly different than it did before the storm’s onset.

Notes

1 This quotation was reported in a November 14, 1982, New York Times story.

2 Author’s calculations based on data from an October 2019 Pew Charitable Trusts issue brief, figure 3.

3 Author’s calculations based on data from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2020, G.19 statistical release, July 8, available online.

4 One FYES is equivalent to one full-time student who is taking 30 credits in an academic year in Michigan. So, the total number of full-year equivalent students is calculated by taking the total number of credit hours taken at all of Michigan’s public universities for the year divided by 30 credits.

5 Author’s calculations based on data from the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency.

7 Available online by subscription.

8 Available online by subscription.

9 There are also some nonprofit schools that primarily provide higher education online, such as Southern New Hampshire University.