Rural Economies and Globalization

Rural economies in the U.S. are on the front lines of the upheavals associated with globalization. Many rural economic engines are based on commodity production and traded goods—namely, routinized manufactured products and production agriculture. Such industries are coming under competitive pressure from overseas economies that often enjoy significant cost advantages. These are also the types of production activities that regularly experience sharp productivity gains—and attendant labor efficiencies—as a result of technical progress. As a result, many rural work forces are shrinking; rural economies are, on average, underperforming metropolitan area economies. In response, rural areas are searching for ways to become innovative in nature rather than commodity-based as a way to stay vibrant.

The Global Chicago Center of the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations recently convened its second in a series of meetings intended to assist print journalists connect global events with their readerships. The Global Chicago Center has fashioned a web-based guide for media so that local experts on global affairs can be readily sourced by local journalists. This particular meeting in Chicago focused on newspaper journalists in rural regions of the Midwest. Experts and analysts of rural regions met with the journalists to discuss the ways in which globalization is affecting rural economies and what, if anything, can be done about it. For some rural regions, the answer to the latter question is not much.

Due to high productivity on farms, which has helped give Americans the world’s highest standard of living, production agriculture employs relatively few people. Indeed, farmers account for only 2 percent of the U.S. work force and only 11 percent of rural population.

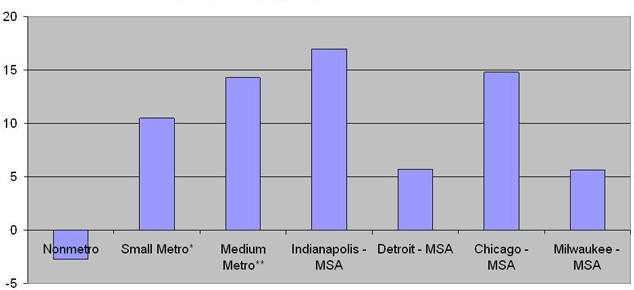

Manufacturing now dominates many more rural counties than does agriculture, but the type of manufacturing activity there is vulnerable to global competition and displacement. Over the past 50 years, manufacturing plants locating in rural areas have been seeking a low-cost environment and high-quality but lower-skilled rural workers. Nonetheless, technological progress and heightened global competition often have an adverse impact on these operations. As the figure below shows, metropolitan economies in the Seventh District are easily outperforming nonmetropolitan areas on average.

1. Midwest population growth, 1990-2004, percent change

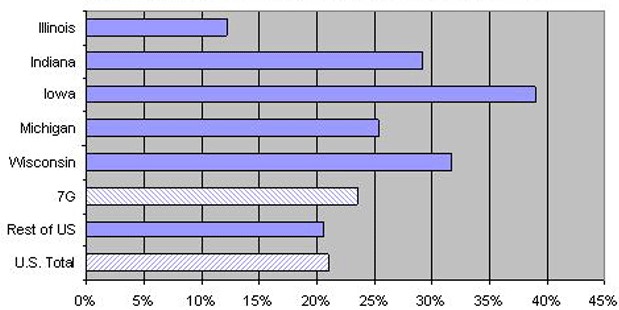

2. Rural population as a percent of total population, 2000

Why are metropolitan areas adapting more successfully to globalization? At least part of the answer is that innovative industries or groups of activities have more frequently emerged or prospered in urban areas. And innovative companies can sometimes stay one step ahead of the competition—even low-cost competition—by spinning out new products and conducting business with new processes and management techniques.

But all is not lost in rural areas, according to Lee Munnich of the Humphrey Institute at the University of Minnesota. Munnich has studied what he calls “rural knowledge clusters” in Minnesota. These clusters are proximate groups of innovative, inter-related firms, workers, entrepreneurs and, sometimes, educational institutions. They have managed to thrive, often building an industry related to local features or activities such as the snowmobile “cluster” of leading firms in northwest Minnesota. Other knowledge clusters in Minnesota identified by Munnich include:

- Mankato: wireless and radio frequency technology

- Alexandria: automation/motion control technology

- Winona: advanced composite materials

- Northwest Minnesota: recreational transport equipment

- Southwest Minnesota: precision agricultural equipment

Munnich argues that you cannot build a knowledge cluster from scratch, but you can identify existing clusters and build on them. Building blocks include programs to encourage further entrepreneurship, mentor and provide seed capital for new ventures, and create complementary work force programs at the local colleges.

One who agrees with Munnich’s assessment that rural economies are struggling is Mark Drabenstott, Vice President at the Kansas City Fed and Director of their Center for the Study of Rural America. Drabenstott reports that the top 310 fastest growing counties in the U.S. over the past ten years accounted for three-fourths of total U.S. economic growth and that only eight of these were nonmetropolitan counties. Rural areas must find ways to achieve the critical mass of talent and innovation that are needed to compete in today’s global economy.

According to Drabenstott, finding ways to develop rural economies toward greater scale and innovation is far from simple. For one thing, rural areas vary enormously. So what might be a successful path to redevelopment in one area might be entirely different from what will work in another area.

Another hurdle is that rural areas themselves often lack the local capacity to understand and react to global phenomena. And nationally, few resources are being devoted to assisting rural economies in handling their development challenges. For instance, almost two-thirds of USDA expenditures are earmarked for payments and subsidies for commodity agriculture; only 0.5 percent is going toward rural economic development.

Drabenstott sees a few bright spots in rural America. U.S. agricultural exports have been steadily shifting away from commodities and toward “consumer” food products and other higher value added agriculture. So too, many rural manufacturing firms are adapting to global competition by adopting world class manufacturing processes. Immigrants are also bringing their entrepreneurial enthusiasm to parts of rural America, and foreign companies are also scouring rural economies for investment opportunities.

As the Global Chicago Center sees it, newspaper journalists in rural areas can help their readers and their communities in understanding and reacting to the challenges and opportunities that accompany globalization.