Automotive wages in flux

As the “Detroit 3” automotive companies have experienced shrinking profits and market share, many midwestern communities have experienced falling jobs, income, tax revenues and public services—to say nothing of the households and families working in the industry. This summer, automotive workers and communities are watching closely as the terms of automotive employment—especially wages—are being renegotiated. On July 20, for example, the UAW labor union opens contract negotiations with Ford and Chrysler (July 23 for General Motors) for contracts that will run for 4 years. And earlier this month, auto parts maker Delphi announced settlement terms with its workers as it undergoes operational restructuring. Only four Delphi production plants will remain in operation in the U.S. as its customers will source parts from its overseas operations or from alternative suppliers. Remaining Delphi production workers will be on the receiving end of cuts to health care benefits, employment security, retirement and wages. Wages for production workers will be reduced from $27 per hour to a maximum of $18, $14 for new hires.

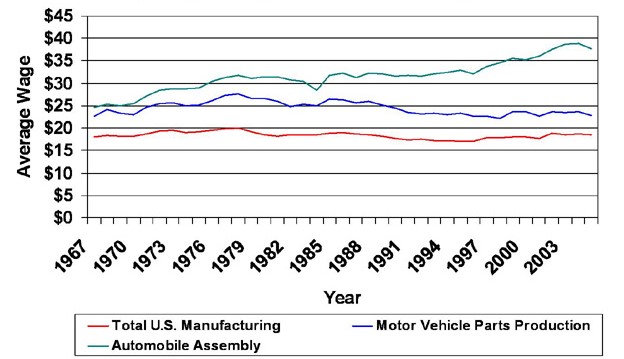

How should we view the wage settlements as they are announced in coming months? One perspective is to compare them to average wages for production workers in U.S. manufacturing. Production workers are typically those who have few or no supervisory roles in manufacturing plants; in other words, most assembly line workers would fall into this category. The chart below displays average wages for production workers back to 1967. These wages represent the average in compensation for overtime and regular time. The wages are expressed in current dollars, adjusted over time for changing prices by the Consumer Price Index.

The bottom line shows that, across all manufacturing industries, average wages have remained largely flat since 1967, ranging between $17 and $20 per hour. Wages were rising until 1980. With several deviations, the average wage settled at $ 18.59 in 2005, which is the latest available data from this particular source.

In the same graph, we can see that that production workers in motor vehicle parts industries (blue line) have fared somewhat better over time, but that their wages have been converging with the remainder of manufacturing workers since the 1980s.

Workers in the automotive assembly industry (green line) are smaller in number than those in parts production. In the U.S., there are approximately three workers in parts production for every worker in an assembly plant. Unlike their brethren in parts production, assembly workers’ wages have been generally rising since 1967. By 2005, the U.S. Census Bureau reported an average production wage of $35.84.

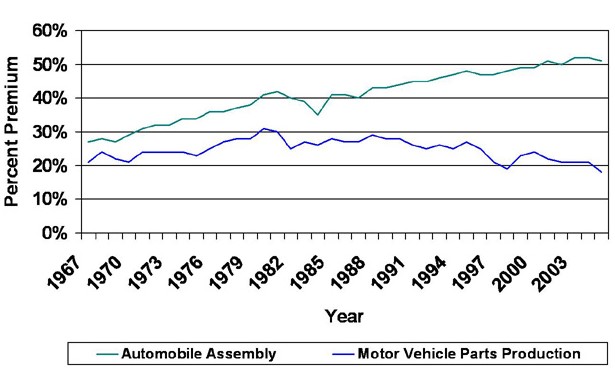

The second graph below plots the premiums in wages for automotive workers. This premium is expressed as the percent by which wages exceed the average of all U.S. production workers across all industries. As of year 2005, the average wages of automotive assembly workers topped their counterparts by 50 percent. For motor vehicle parts workers, the wage premium has fallen below 20 percent from a peak of 31 percent in 1980. Approximately one-third of workers in the parts industry are represented by labor unions versus three-fourths of domestic assembly workers.

1. Real average hourly wage changes in U.S. (as adjusted by the CPI-U where 2007=100)

Note: Pre-1998/post-1997 data are not strictly comparable due to definitional changes.

2. Wage premiums vs. total manufacturing in the U.S.

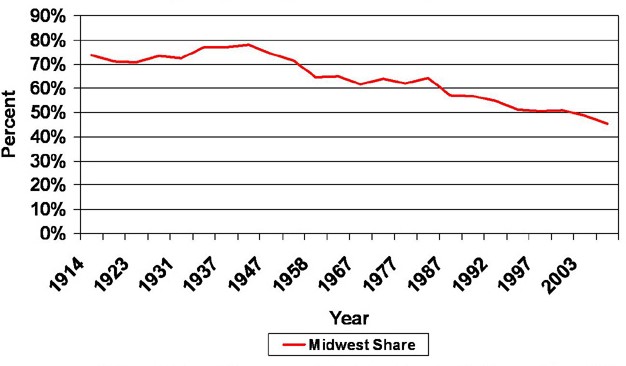

Declining employment has accompanied softening wages in many instances. From a geographic perspective, declining automotive jobs is nothing new for many midwestern states and communities. The industry was highly concentrated in the Midwest throughout the first half of the twentieth century but afterward began to disperse—first to other U.S. states and later around the globe. Considering domestic employment in automotive parts and assembly combined, the next graph shows that the states of Ohio, Michigan and Indiana accounted for over three-fourths of automotive employment through World War II. By 2005, their employment share had fallen under one-half.

3. Midwest share of U.S. automotive employment, 1914-2007 (Ohio, Michigan and Indiana)

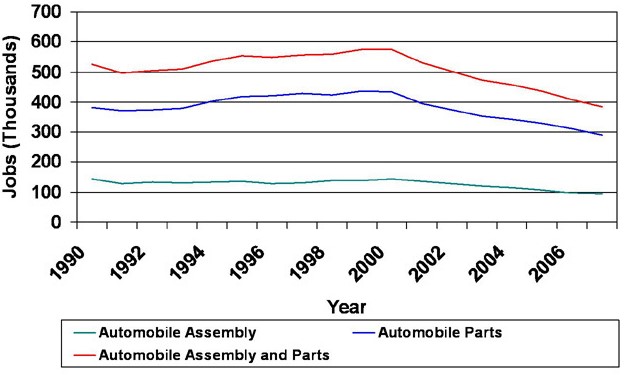

During the current decade, the automotive job decline has been precipitous. The final graphic (below) indicates that the three-state decline in automotive jobs has fallen by almost one-third since year 2000, from 576,000 to 383,000 over the first half of 2007.

4. Automotive employment (Ohio, Michigan and Indiana)

The reasons for these employment declines are several.

- As always, productivity gains are reducing the labor content in automotive production. Labor hours per vehicle assembled by the “Detroit 3” car makers, for example, declined from 24–28 hours in 2002 to 22–23 hours in 2006. Beyond assembly, estimates by Martin Baily of the McKinsey Institute and the Institute for International Economics report that labor hours to produce an auto in North America, including parts, are decreasing at an annual average of 1.7 percent annually since 1987, and are now approaching 100 hours total.

- Globalization of production has resulted in both off-shore operations and competitive pressures on domestic producers. Since 1996, the import share of light vehicle sales has increased from 12 percent of sales to 20 percent, year to date. Approximately one-quarter of domestically used automotive parts are now sourced abroad.

- Despite some periods of re-concentration over the past 2 decades and the siting of many new plants in various Midwest communities in recent decades, the overall industry continues to disperse to other states, especially in the South.

Note: Thomas Klier contributed to this entry.