How should states tax business?

As much of the Midwest economy struggles to boost its economic performance and as Midwest governments try to maintain funding for public services, the subject of state and local business taxes arises. This summer, the state of Michigan replaced its innovative but contentious “single business tax” with two lesser taxes, one on business income and the other on business gross receipts. Meanwhile, Illinois’ Governor Blagojevich proposed a hefty tax on business gross receipts that was to begin in 2008. That tax proposal was defeated even as the Governor railed against the interests of high-powered lobbyists “who eat fancy steaks” and “shuffle around in Gucci loafers.” These and other new developments in state–local business taxation will be discussed and analyzed by some of the nation’s leading tax experts at a Bank conference this coming September 17.

What are business taxes, and how should they be viewed? By definition, and in accounting for them, business taxes are any taxes collected from businesses and legally imposed on business revenue, property, assets, sales, right to do business and inputs to production. Measured in this way, business taxes are estimated in a recent study by Ernst & Young to have been $554 billion in 2006, accounting for 45 percent of state–local government tax collections. By this reckoning, their share of these tax collections has fallen by only a couple of percentage points since 1990.

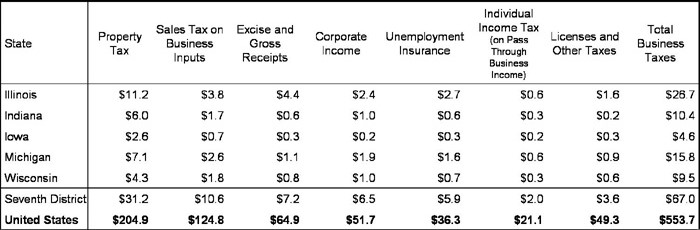

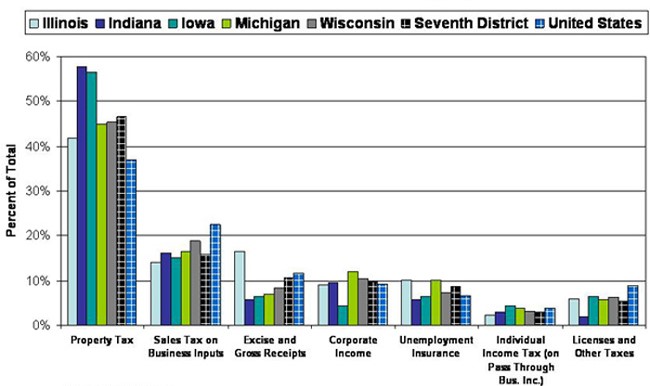

The table below, drawn from the same study, displays business tax collections by type for Seventh District states and the U.S. The following graph allocates property taxes by type into shares of the total collection. Property taxes, which are largely administered and collected by local governments, comprise almost 50 percent of business taxes. Seventh District states have historically drawn on these sources since local governments tend to be prominent here and because the Midwest economy has historically concentrated in property-rich sectors, namely agriculture and manufacturing.

It may surprise many to find that “retail” sales taxes on business transactions rank second in business tax share. Though it is often thought of as a tax primarily levied on consumers at the point of final sale, many intermediate purchases of goods and services between businesses (B to B) are not exempted from it. By one estimate, as much as 40 percent of retail sales tax collections in the U.S. may be collected from B to B sales.

Table 1. Seventh District state and local business taxes by type, FY2006 (dollars in billions)

Figure 1. State and local business taxes by type, FY2006

In fashioning business-type taxes, policymakers seem to be motivated in two primary ways. First, business taxes are often seen as a popular and expedient way of raising revenue for public services and do so at the expense of the business owners. There is a common notion that such taxes are “progressive” and are drawn from the wealth of well-to-do individuals. However, business-type taxes are imposed on certain transactions and not people per se. For example, a particular tax may be called a “retail” tax if it is imposed on telephone or electricity consumption, implying that the consumer is bearing the burden. But, the same tax may be called a “gross receipts” tax when levied directly on the public utility, implying that unidentified “business owners” are bearing the burden of the tax. Yet, in every action in collecting either tax, they are identical. “Who puts the nickel in tax collection box” makes no difference in real impact.

Similarly, while a business tax may be legally written to fall on the purchase of a business input or on the income of a corporation, behavioral adjustments take place in response to the tax that ultimately shift the final burden of the tax. Most commonly, excessive taxes are shifted forward into the prices of goods purchased by consumers—rich and poor alike; or taxes may be shifted backwards onto people who own the factors of production—laborers as well as nonworking households of various income strata.

If it is true that business taxes are shifted, why do we see that business organizations and business owners vigorously fight business tax hikes in state legislatures and in local city councils? Part of the answer is that taxes are only shifted in the long run. In the meantime, because business operators and owners cannot quickly adjust their behavior in response to tax hikes, the tax burdens may indeed fall heavily on them personally. Only after varying periods of time may businesses fully take offsetting actions, such as reducing investment and labor, retrenching production, or moving to other locales. And looking forward, many opportunities for business expansion may be nullified because of disincentives that are attendant to the expanded taxation.

In this light, the other major consideration of policymakers comes to the fore. State and local policymakers worry about their competitiveness in setting business tax policy. In the United States, “tax competition” is highly active among state and local governments. As localities compete for both jobs and tax revenues, taxes do not generally stray too far out of line. Outwardly, states keep their general business tax structures in line with their neighbors so as not to discourage business investment. So too, states and localities often offer generous and other selective tax abatements.

Tax competition serves not only to keep business taxes from being punitive, but in the competition for local investment, localities are often forthcoming in allowing commercial use of land and providing public services to business. In fact, because businesses do directly use public services such as roads, refuse disposal and public safety services, it is clear that business taxes should seldom or never be reduced to zero but should rather cover related costs. Other similar “business generating” costs that have been advanced in this regard include pollution-type taxes, which are more common in Europe, and the business benefits of allowing “limited liability” organization, which may impose costs on governments if businesses fail catastrophically or in unanticipated ways.

Some observers and analysts believe that local governments do not manage well the negotiations with savvy business firms for selective tax subsidies. For this and other reasons related to tax competition, insufficient revenues will be raised to fund basic services to households, such as public education. Accordingly, efforts to limit competition by statute have been advocated, along with proposals to assist governments in bargaining more effectively with arbiters of mobile capital investment.

Is the limiting of tax competition necessary to save governments from themselves? The answers are not yet clear. However, it can be said that local governments are competing on more than the basis of tax competition alone. Several studies have indicated that the quality of life and other household amenities are increasingly the determinants of metropolitan area growth. Local leaders, and especially big city mayors, have responded to this trend by building infrastructure and offering amenities to attract workers—especially educated and skilled work force—to their cities. Such efforts range from festivals and parks to school reform and public safety. Younger people are often the focus, since they are more mobile in their migration patterns. In tandem, cities often couple amenity initiatives with employment strategies such as college internship programs with local firms, recruitment fairs and regional marketing.

Governments also compete in providing public services to business, and they also construct the regulatory and legal environment in which businesses operate. In considering where and whether to invest, businesses must often look to an uncertain future. In choosing where to invest, they accordingly prefer to have some certainty with respect to state and local government behavior toward business activity. They may ask themselves: Do the state and local governments seem to be committed to standing as an attentive and steady partner in providing services as businesses’ needs change over time? Or has the past record of state and local government been punitive and myopic in expanding business taxation when revenue shortfalls arise?