The auto region continues to reshape

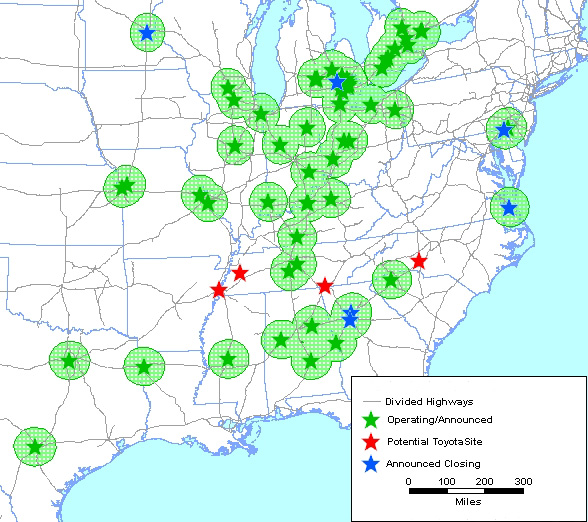

On Wednesday, February 14, DaimlerChrysler AG announced a restructuring of its North American Chrysler Group. Adjusting its vehicle production capacity to continued market share losses, the company will eliminate shifts at three different assembly plants (Newark, DE, and Warren, MI, in 2007, St. Louis, MO, in 2008) and idle the Newark plant in 2009 (that plant is identified in figure 1 by a blue star).

Conversely, Toyota Motor Corporation, in response to strong growth in the North American market, is about to announce where it will build its next vehicle assembly plant in North America. The company is looking to expand its footprint of production facilities to meet its goal of achieving 60% of local production. Several weeks ago a story appeared in the Wall Street Journal identifying a handful of locations that are being considered by the company (identified in figure 1 by the red stars).

What are the main drivers underlying a decision to locate an assembly plant? This blog suggests a number of influences.

First, let’s briefly outline the current industry geography. Today there are 68 full-size assembly plants (plus two currently under construction) producing cars and light trucks, such as minivans and sport utility vehicles, in the U.S. and Canada. Figure 1 shows them all with the exception of the lone West Coast plant (the GM-Toyota joint venture called NUMMI, which is located in Fremont, California, in the San Francisco Bay area).

1. Light vehicle assembly plants

The striking feature of figure 1 is the high degree of clustering exhibited by this industry. The vast majority of the plants are located in the interior of the country, extending south from Michigan and Ontario in a rather narrow band. In addition, one can see the importance of transportation infrastructure. It is a key location factor for manufacturing industries, such as the auto sector, which are operating based on lean manufacturing principles. Interstate highways and rail lines (the map only shows interstate highways) are enabling assembly facilities to connect with their supplier base on a just-in-time basis.

In a second quarter 2006 issue of Economic Perspectives, Thomas Klier and Daniel P. McMillen analyzed how the geography of assembly (as well as auto parts production) facilities has evolved in the U.S. and Canada since 1980. They identify noticeable changes in the industry’s geography. These changes, however, occurred gradually, in evolutionary fashion over the last three decades.

Two major trends have shaped the footprint of today’s assembly facilities: Foreign-owned assembly plants gravitated towards the southern end of the auto region, preferring warmer climes and a work force that had not previously been employed in auto assembly. With two exceptions, all of foreign-owned assembly plants operating today have been so-called greenfield plants, i.e., newly constructed plants on land that was previously not a manufacturing site. The domestic assembly facilities, on the other hand, re-grouped in the northern end of today’s auto region after decades of serving the major population centers directly. They began shutting down their coastal plants in the late 1970s in response to the changing economics of transportation costs associated with serving the national market.

And so today’s auto region with a clearly defined north-south extension came about. Concentration of locations remains very important for this industry: Assembly plants need to be near their supplier base. Yet there are reasons for them not to be right next to one another. Assembly plants are large manufacturing facilities drawing their work force from an area larger than the immediate vicinity. Notice in figure 1 how many of the 50-mile circles drawn around assembly plant locations do not overlap.

How do the latest developments fit the ongoing re-shaping of the auto region described above? Chrysler, in line with recent restructurings last year by GM and Ford (plant closings in Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota, and Virginia as indicated by the other blue stars on the map), is trimming a production facility at the periphery of its manufacturing footprint. As a result, the domestic vehicle production has recently become more concentrated in the Midwest than it has been for many decades. For example, the announced closing of the Delaware assembly plant leaves only one vehicle assembly facility in the Northeast (there were six as recently as 1980). Should Toyota choose one of the locations mentioned in the press, it could best be described as “in-fill” development. It would fill a gap in the auto region which was extended considerably further south by assembly plants that located in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina during the 1990s.

And so the combination of recently announced plant closures and a soon to be announced plant opening are reinforcing the shaping of an auto region that is located in the interior of the country, with a north-south orientation, extending northeast into Ontario.

What are the implications of this analysis for Michigan and the Midwest? In Michigan especially, intense discussion is under way concerning what role, if any, public policy can play in shaping the region’s future. Currently, the competitive struggles of the domestic automotive companies (formerly known as the Big Three) and their suppliers are affecting the Midwest economy. Surely, much will depend on individual companies’ abilities to restructure and find ways forward. However, as the research by Klier and McMillen suggests, at the same time as traditional automotive companies are retrenching, they are also regrouping closer to the traditional (midwestern) center of the automotive industry. Actions speak louder than words in many instances. Here, locational decisions strongly suggest that the Midwest remains a highly productive place to manufacture automotive parts and vehicles. The region’s advantages lie in the fact that: 1) it is already the center of production so that proximity to suppliers makes it cost effective in many respects, 2) its transportation infrastructure is highly developed to serve manufacturing, and 3) its existing work force is highly skilled and trained in these industries. Accordingly, in addition to moving in new economic directions, local policy actions to help restore the region’s place in manufacturing seem not misplaced.