Michigan—Brakes and Shocks

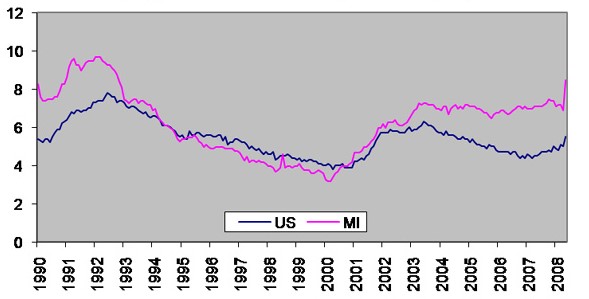

Few outside the state of Michigan are fully aware of its economic woes. Nationally, the U.S. economic slowdown, housing market decline, and rising gasoline prices have captured the headlines. Even within the Midwest, spring and early summer flooding have dominated our news. Somewhat lost in the shuffle, Michigan payroll jobs are down more than 10% from their peak in June, 2000, representing over 486,000 jobs. Recent developments are no more encouraging. The state’s (preliminary) unemployment rate rose by 1.6 percentage points in May, to a seasonally adjusted 8.5% percent—topping the U.S. rate of 5.5% by 3 full percentage points. Preliminary statistics estimate that payroll jobs in Michigan fell by 68,000 over the month (seasonally adjusted). Minus Michigan, reported U.S. employment would have grown by 19,000.

1. Unemployment rate Michigan vs. U.S. (seasonally adjusted)

Michigan’s economy currently suffers from unfortunate industry composition, with an added dose of structural shocks to several of its prominent lines of business. In particular, the automotive, tourism, and office furniture sectors are highly sensitive to national swings in economic activity. As the U.S. economy slows, such industries tend to decline even more. Moreover, in the case of automotive and tourism, structural changes are tending to further dampen economic production and hiring in Michigan.

Michigan’s economy remains far and away the nation’s most concentrated in motor vehicle manufacturing. Its overall employment concentration lies 8.5 times the national average in combined automotive parts and assembly, with many attendant jobs in manufacturing, distribution, and professional service companies that are customers or vendors to automotive producers.

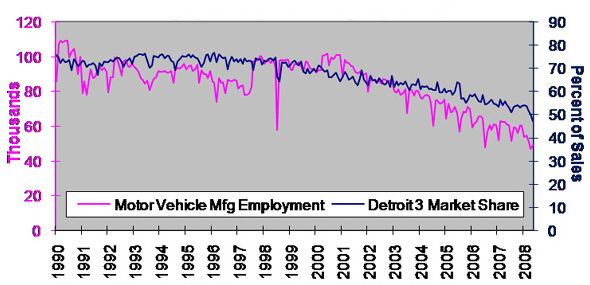

While U.S. automotive sales remained robust until recently, the former Big Three automakers (now more appropriately called the Detroit Three) and their suppliers have been steadily losing market share to imports and to foreign nameplate producers located elsewhere in the U.S. As of May 2008, market share of the Detroit Three automakers had fallen from 67.8% in 2000 to 47.2%. Prominent parts supply companies, including Delphi, Dana, Tower, and Collins & Aikman, have folded, merged, or are currently trying to emerge from bankruptcy.

2. Big 3 market share and Michigan motor vehicle manufacturing employment (seasonally adjusted)

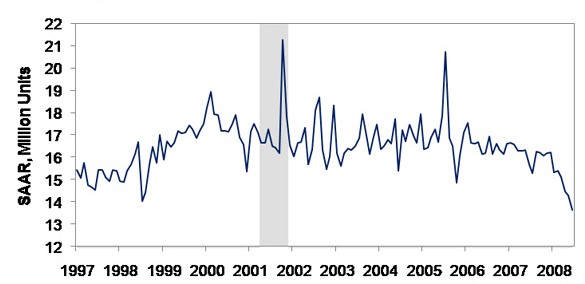

With the recent economic slowdown, automotive sales are resuming their cyclical pattern of retrenchment. To some degree, the historical behavior of sales declines was allayed in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, when automakers offered generous sales and financing incentives to prospective buyers. However, today’s slowing economy appears to be leading consumers to avoid the purchase of new autos. As discussed recently at our annual Automotive Outlook Symposium, rising gasoline prices are curbing driving behavior while draining household income.

3. Light vehicle retail sales (imported and domestic)

The recent run-up in gasoline prices has magnified loss of market share and erosion of profitability of the Detroit Three automakers and their suppliers. Over the past year, the Detroit 3 share of domestic sales has fallen by 7.1 percentage points. To some degree, this repeats the pattern of the 1970s when U.S. consumers turned to (imported) foreign-domiciled automakers who offered vehicles with greater fuel efficiency. Domestic automakers are more reliant on trucks than on cars, and they tend to lag foreign manufacturers on fuel efficiency.

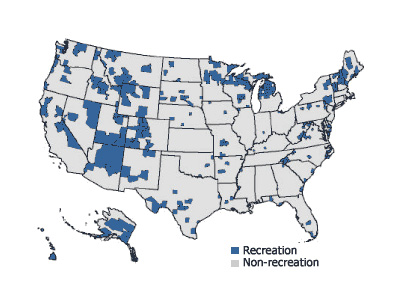

Not only the automotive sector has been impacted by rising energy prices. Michigan’s tourism, recreation, and hospitality industry has taken on added importance in the wake of the state’s waning automotive industry presence. Many parts of western and northern Michigan feature attractive scenic and semi-rural locales for retirement, recreational living, and seasonal tourism. In addition to its many inland lakes, the state is endowed with 3,126 miles of Great Lakes shoreline, which is attractive for boating, fishing, and other recreational activities like hiking, cycling, and golf. In particular, the state registers nearly as many boats as Florida or California. Such activities in Michigan are especially related to vacation and seasonal homes. As of the last Census, 5.6 percent of homes in Michigan were of this variety versus a national average of 3.1 percent.

The map below shows recreational counties as designated by demographers Calvin Beale and Kenneth Johnson. The northern tier counties of Michigan and Wisconsin have long been recreational destinations, especially for Michiganders and residents of the greater Midwest region.

4. Recreational counties

Recreational spending is highly discretionary on the part of consumers. As household income falls, recreational spending can be easily curtailed by households in an effort to maintain spending on necessities.

Recent declines in Michigan recreational spending are reflected in data collected by the State of Michigan on sales tax collections imposed on overnight lodging. These accord with declining lodging occupancy rates collected by the industry. Both are down so far in 2008 on a year over year basis. A broader index of Michigan’s tourism activity is displaying a modest uptick for the first quarter of 2008 versus one year ago. However, with rising gasoline prices, the index (and activity) is expected to trend lower in coming months.

Two additional factors may be restraining recreation sector growth in Michigan. Michigan’s recreational counties are characterized by ownership of second homes. The run-up in housing prices and the subsequent rash of foreclosures and price declines have been especially severe in recreational/seasonal home locales. Seasonal home residents who have experienced asset price losses on their second homes may be especially aggressive in re-building their household balance sheets by restraining current spending in the second-home locales.

The second, more obvious, factor affecting recreation this year is rising gasoline prices which raise both travel costs to vacation locales and, in Michigan’s case, the cost of boating. However, some domestic vacation locales may benefit from a backwash effect as households choose nearby attractions rather than long distance adventures. Nonetheless, in most instances, the overall effect tends to be a dampening. For these reasons, tourism industry analysts in Michigan are forecasting declines in tourism activity for 2008.

In addition to automotive and recreation sectors, Michigan has a strong presence in the furniture sector. Indeed, Western Michigan hosts the nation’s largest concentration of makers of office furniture. This industry took shape in the late nineteenth century during rapid industrial growth, which was accompanied by rapid growth in office employment. Taking advantage of the region’s abundant hardwoods and skilled immigrant craftsmen, most furniture companies in the area had developed as manufacturers of high-end traditional style home furnishings. However, the labor-intensive wood furniture industry declined in Grand Rapids and other northern centers by the mid-1900s due to competition from Southern producers. In response, the Grand Rapids industry shifted its focus from household to office furniture, led by companies that would become industry giants: Steelcase, Haworth, and Herman Miller.

The U.S. Census reports that the state is the nation’s leading producer of office furniture and fixtures, with 17,000 direct employees in 2005. Broadly defined, the state’s industry share accounts for 24% of the nation’s shipments. (Michigan’s share is larger according to the way that the industry trade association defines the industry).

Michigan’s office furniture companies have been affected by competition from China and other low-cost locales. Despite competitive pressures, the companies have successfully responded in two ways. To some extent, producers have moved or offshored production of select product lines to low-cost locales while maintaining high value added and custom design services domestically. More importantly, these companies are characterized by great innovation in product and processes. They have succeeded and grown by offering custom and advanced products and services.

However, office furniture sales and production have been highly cyclical. The industry experienced sagging sales in the late 1980s and early 1990s when U.S. businesses downsized middle management positions and as the U.S. economy sagged. So too, the “technology bust” years that began the current decade saw a falloff in demand for office systems and furniture, especially in the IT sector.

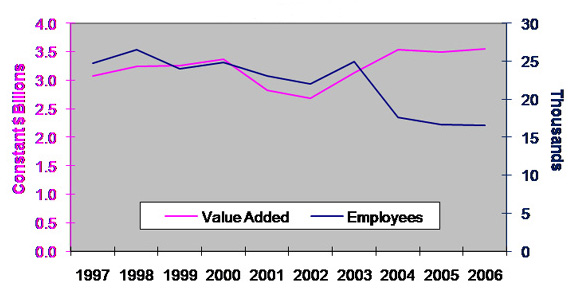

5. Michigan office furniture industry value added and employment

So far in the current environment, industry production has been holding up well. However, if industry observers are correct, office furniture may be “one more shoe about to drop” in Michigan. An opinion poll of office furniture executives has been flashing negative for the near term outlook, and the industry association has recently lowered its forecast of 2008 production.

If such expectations develop, this would further dampen economic activity and the labor market in Michigan. Cyclicality of certain businesses can be planned for and absorbed by states such as Michigan and its neighbors. However, cyclical episodes in the economy can be exceptionally severe when shocks such as rising energy prices are in play and when longer term structural changes are taking place, as they are in Michigan’s automotive sector.

Thanks to Graham McKee and Vanessa Haleco-Meyer for assistance.