Michigan Economic Adjustment: What Role Migration?

What role does migration play in helping regions such as Southeast Michigan adjust to profound economic shocks? For the most part, out-migration is not usually the favored choice of families who have strong social and economic ties to their communities and region. Regions under duress first look to rebuild and reinvent their local economy. But Americans are also a nomadic people. And so, households also adjust to negative economic shocks by picking up and moving to where opportunities for employment and income are more favorable. During the last century, for example, southerners migrated northward in search of the high-paying factory jobs located here, while the population from the Northeast and Midwest continued to flow westward as economies developed in California and other parts of the West. It is not surprising then to find that some Michigan residents may migrate elsewhere unless (or until) economic conditions turn around.

Unlike most U.S. states, Michigan’s economy has not enjoyed any net growth during the entire decade. Decline in the state’s automotive industry has kept its economy reeling. In some ways, this experience is reminiscent of conditions from two decades ago. At that time, the domestic automotive industry struggled with energy and gasoline price spikes that had begun during the mid-1970s. Much as today, the automotive fleets of Chrysler, General Motors, and Ford—known then as the Big Three—had been designed on the larger side, which was better suited to a bygone era of cheap gasoline. Accordingly, auto sales by domestic producers were sharply impacted by OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) gas price spikes, by a federal gasoline rationing program, and by imports of small, fuel-efficient vehicles from (then mostly Japanese) competitors.

Even so, by the beginning of the 1980s, Detroit was making a comeback with its own small cars; back then, the tail winds from a strong U.S. economy was lifting overall automotive sales. Alas, a second global energy price spike, along with two U.S. recessions during the early 1980s, exerted a horrific effect on Michigan and on the Midwest manufacturing belt. Foreign markets were of little help during this era of a rapidly rising dollar, and the region’s agricultural sector experienced profound declines in prices and land values.

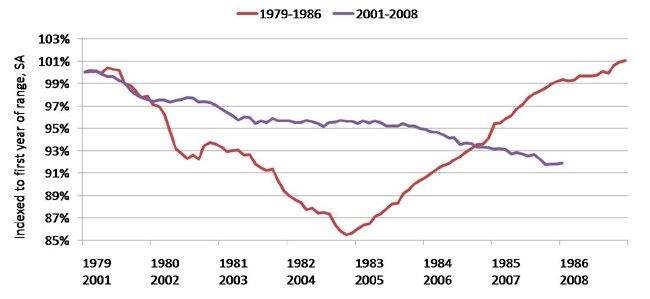

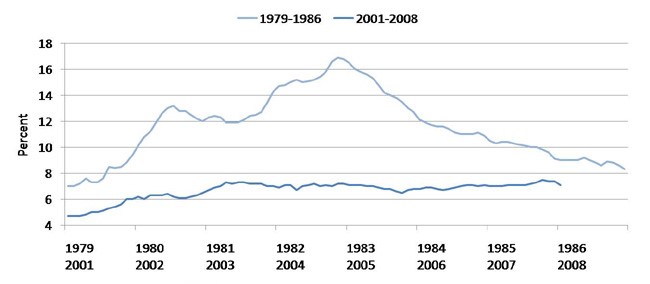

The chart below overlays the payroll job trends of that era with that of the past seven years. Following a peak in Michigan job levels in 1979, jobs declined at a pace of over 2% per year for the next four years before bottoming out at the beginning of 1983. In comparison, the recent payroll job decreases in Michigan have been less dramatic, with a cumulative decline of 5 percent from 2001 to date. Similarly, the average state unemployment for all of Michigan had reached 16 percent by 1983, over double what it is today (see chart below).

1. Payroll job loss in Michigan

2. Michigan unemployment rate

However, it should be noted that Michigan’s economic decline in the current decade has gone on much longer than its decline of the early 1980s. By 1983, Michigan’s payroll employment had begun to climb once again as U.S. consumer purchases of autos rose and as excess inventories of autos were sold off. While recent declines have been less precipitous, the cumulative effect has been no less profound. Annual employment in Michigan has not climbed over the past 7 years, and now stands at over 6% below its level at the beginning of 2001.

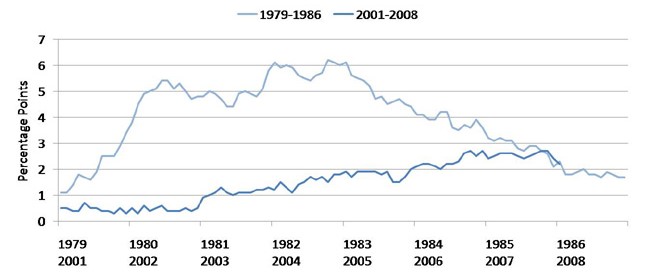

How did Michigan households adjust to diminished job and income opportunities in Michigan during the 1980s? In part, Michigan workers and their families left the state in search of opportunities in other regions. Households decide to migrate based on more than local conditions. That is, they also base their decisions on labor market conditions in alternative regions of the country. Although the overall U.S. economy was experiencing recessionary conditions during the early 1980s, Midwest labor markets were far and away more affected. For instance, rising energy prices were spurring economic investment (and jobs) in energy-producing regions, such as Texas–Louisiana and in the western coal fields. Meanwhile, the first surge in high-tech computing production was underway in New England and California, and strong economies were emerging in regions where post-1970s defense spending was growing. The chart below illustrates the difference in unemployment rates between Michigan and the overall U.S. at that time. Michigan’s unemployment rate was 5–6 percentage points above the nation’s from 1980–83.

3. Michigan and U.S. difference in unemployment rates

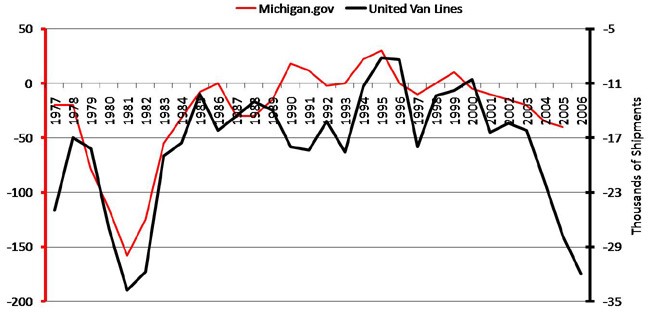

As the chart below suggests, more households had been moving out of Michigan than moving in throughout the 1970s, with a net out-migration exceeding 50,000 per year by 1974–75. However, this number tripled by 1981–82, exceeding 150,000 per year. Economic recovery eventually unfolded in Michigan, but it did not pull along net migration into Michigan until the early 1990s.

4. Net migration comparison by source

Today, labor market conditions in Michigan, while the worst in the U.S., look mild compared with that of the 1970s and 1980s. Still, the pattern of continual payroll job losses since 2001 gives the impression of long-term structural decline rather than a short-term episode. So far, the pace of out-migration from Michigan has reported to be milder as well, averaging -20,000 per year from 2001 to 2006. A contributing factor for restrained out-migration may be the difference in the age demographics of the population between then and now. Historically, those aged 20–39 have been much more likely to pull up stakes and move out of state. Michigan’s population has aged, with only 37% of the adult population of prime (moving) age today versus 48% in 1980.

Still, out-migration from Michigan may yet increase somewhat. Out-migration from the state has been picking up lately as the decade wears on and employment continues to decline. United Van Lines (UVL) has been tracking data on in-movements versus out-movements of its residential moves by state for many years, and these data tend to accord fairly well with government statistical trends on net migration of population. Recent UVL data for 2007 suggest that out-migration of households exceeded in-migration by a 2 to 1 ratio, while the level of net out-migration of moving trucks is approaching the previous trough experienced in 1981.

Many policy leaders and local communities in Michigan are determined not to let the state’s growth fall further into negative territory. There are concerted initiatives to diversify the region’s economy toward technology industries, services, and recreation-tourism. For example, three of Michigan’s universities—the University of Michigan, Michigan State, and Wayne State—are teaming up to fashion a research corridor that will further stimulate innovation in the state. The research synergies of the three hope to improve technology transfer, share resources, and attract jobs to the state.

Such efforts may well turn around the state’s fortunes over the long term. But following a long and difficult decade for many of the state’s residents, the road ahead does not look any easier—at least for the immediate future. As the U.S. economy slows during the first half of 2008, domestic automotive sales (and production) are also expected to soften.