Tending the Northern Border

Despite the fact that the U.S. is Canada’s largest trading partner and vice versa, northern border crossing conditions have sometimes been given short shrift. Today, in some places along the border, freight and travelers use outdated infrastructure in a post 9/11 world where security concerns have tended to slow cross-border movement. Accordingly, suggestions have been raised on both sides of the border to improve passenger and trade flows between the two countries. The Seventh District’s Great Lakes crossings, specifically the Detroit River crossings, are focal points of the growing debate on how best to improve the U.S.–Canada border.

U.S.–Canada Border Crossing Policy

Over the last few years, the majority of U.S. border policies have focused more on Mexico and the flow of immigrants and illicit activity crossing the southern border into the U.S. The heightened attention on the Mexico border has been a concern both to Canadian officials and those whose economic interests depend on cross-border trade between our two countries. For example, automotive-intensive communities in Michigan and much of the surrounding region are especially keen to see border crossings made easier. Much of the fragile North American automotive industry continues to operate with highly inter-connected supply chains that traverse the border between the Midwest and Ontario.

Responding to these concerns, the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program and the Canadian International Council held a forum recently on the challenges and opportunities to improve U.S.–Canada border policy and management. Among the experts to speak at the Brookings forum, Christopher Sands of the Hudson Institute discussed his paper characterizing the U.S.–Canada border policies past and present and recommending a broad framework for improvement. Sands specializes in Canada, U.S.–Canada relations, and North American economic integration. He followed up his appearance at the forum with a meeting here at the Bank.

Sands divides the U.S.–Canada border into four separate traffic corridors. The Great Lakes Corridor sees the highest volume of automobile and truck traffic, most notably the crossings at Detroit–Windsor, Buffalo–Niagara, and Lake Champlain, which connects Montreal and New York City. All Great Lakes crossings see heavy volumes of what Sands calls “amateur” traffic, those who cross rarely, usually on vacation. However, these Great Lakes crossings also provide infrastructure support for commercial goods and services to travel back and forth from both countries’ manufacturing centers. The Michigan border crossings directly link the Great Lakes, where 28% of US GDP is produced, and Ontario, where 41% of Canada’s GDP is produced.

Sands’ Policy Recommendations

Precision, decentralization, and consensus, Sands argues, should serve as the framework for future discussions on improving the border. Precision revolves around defining the specific problem and efficiently targeting and solving it. Decentralization refers to engaging local and regional stakeholders in the policy process while taking care not to stall the process by giving any party too much power. Canadian officials tend to agree more on border initiatives because most of the Canadian population lives near the border and is affected by border policy; they don’t have the regional rivalries exhibited by the debates and issues seen in U.S. border cities and their inland counterparts. Consensus occurs when all levels of government agree on the future of the border and how it should be managed.

Michigan’s Aging Infrastructure

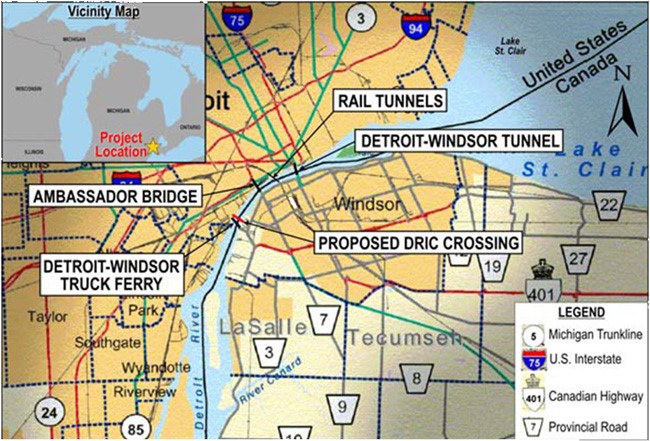

Along the Michigan–Ontario border crossings, infrastructure issues have become pressing. Here, the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit–Windsor Tunnel connect Detroit and the industrial Midwest with Windsor, Ontario, and Highway 401, which heads northeast through the major cities of London, Toronto, and Montreal. Combined with the Blue Water Bridge in Port Huron and the St. Clair rail tunnel just south of it, Michigan possesses some of the more important crossing points, making the state an important player in U.S.–Canada trade. As commercial and passenger traffic continue to cross the border in Detroit, added pressure has been put on infrastructure that is almost 70 years old and isn’t equipped to handle current traffic volumes.

1. Michigan-Ontario border crossings

In recent years, federal, state, and local leaders in the U.S. have advocated for a new Detroit River border crossing approximately 2 miles south of the Ambassador Bridge that would be able to handle increased trade flows as well as implement post 9/11 security upgrades. Adding to the campaign, the Canadian Minister of Transport, Infrastructure, and Communities has publicly stated that Canada’s #1 infrastructure priority is the new Detroit River crossing. Currently, construction on the new bridge complex is scheduled to begin sometime next year, with the opening set for 2013. But first, Detroit and the state of Michigan have short- and long-term issues they must address. The land needed for the new bridge has not yet been purchased by the Michigan Department of Transportation; and critics argue that a new crossing isn’t needed due to slowly decreasing traffic flows. Competing claims for attention have arisen as the Detroit city government and Lansing legislators attempt to agree on expansion and administration plans for Cobo Hall, the region’s premier trade and convention hall, as well as how to contend with education budget deficits and recovery options for a poorly performing state economy.

Independent plans for a competing cross-border bridge in Detroit have further complicated the outlook. The private owner of the Ambassador Bridge has started construction of a second span next to the current Ambassador Bridge, albeit without government permission. (The publicly approved site for the Detroit River International Crossing is Zug Island, 2 miles south of the Ambassador Bridge, which would cross over into southern Windsor, where a new highway accessing Highway 401 is being constructed.) While the private initiative may be advantageous in some respects, its competing site will have the least negative impact on surrounding communities (no displacement of residents anticipated), is the most environmentally friendly, and is the one both nations favor.

Midwestern states along the northern border have keen economic interests in a national border that is secure, yet speedy. Because these interests are somewhat more diffuse throughout most of the remaining states, Midwestern residents would do well to take part in border-improving policy discussions.