What are the opportunities in central cities?

Since at least the 1960s, central cities of large metropolitan areas have experienced challenging times. In many cases, large shares of the population and jobs have shifted from these central cities to their suburbs. More recently, over the past two decades, central cities’ travails have eased somewhat; the declines in the number of households and jobs have abated, and in some instances, these negative trends have reversed. Understanding the reasons behind these trends can be helpful in fashioning public policies to encourage the redevelopment of central cities.

The Chicago metropolitan area’s experience may be especially helpful in informing policy throughout the Midwest states. While the Chicago area has shared a common course of development with its neighbors in the Great Lakes region, its central city has outperformed its counterparts over the past 20 years. The population of the Chicago area’s central city has grown by an estimated 1.9%, or 53,000, since 1990. In comparison, the central cities of the eight remaining largest Great Lakes metropolitan areas have clocked a 9% loss1. As for employment located in the central cities, from 1990 through 2004, the Chicago area’s city lost 4.6%, while those of the other areas lost 6.5%.

1. Central city percent change in jobs and population

Why have central cities such as Chicago and the Twin Cities experienced some rebound? Two major reasons have been advanced. For one, it is clear that there has been a reawakening of interest in living in central cities that relates to their unique amenities and features. Gentrification in many cities has focused on those neighborhoods that contain interesting architecture and history—not to mention lively entertainment scenes. In addition, big city mayors have capitalized on renewed interest in city living by lavishing attention on amenities such as outdoor recreation, lively shopping and arts districts, scenic streetscapes and waterfronts, and urban festivals.

In a recent study of residential location in the City of Chicago versus suburban areas, Bill Sander and I document the specific characteristics of urban denizens versus suburbanites for both 1990 and 2000. The importance of city services to households is apparent from our findings concerning their demographic characteristics. For example, with an eye on the quality or reputation of city schools, household adults with children of school age are much more likely to choose the suburbs over the city. As for the general importance of amenities, diversity, and built environment, we find higher educational attainment to positively affect households’ decisions to choose central city residence. In 1990, those with a four-year college degree were no more likely to live in the city; by year 2000, such householders were 4% more likely to live in the city rather than the suburbs.

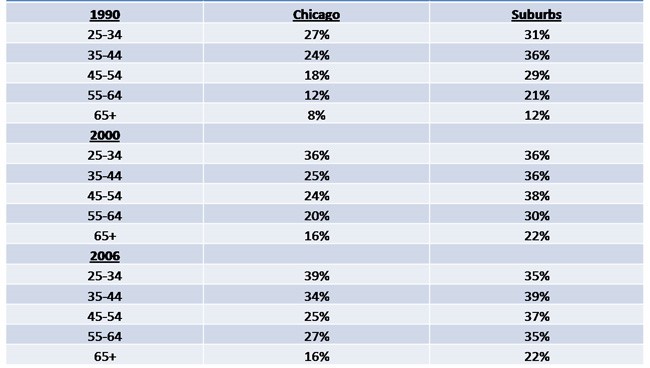

The education-related aspect of urbanization is evident in the changing composition of Chicago’s residents. In 1990, 19% of all working age adults living in the city had attained a college degree. By year 2000, this proportion had grown to 26%. Gains among the younger adults were most striking. As shown below, for adults aged 25–34, the college attainment share had grown to 39% by 2006. Growth since 1990 in college attainment of young adults living in the city reversed the suburban advantage of 1990. On average, by 2006, college attainment of young adults in the city exceeded that of their counterparts in suburban areas. The number of those with a bachelor’s degree residing in the city grew by over 50% over the 1990s (not shown).2

2. Percentage college graduates by age in the city of Chicago and suburbs, 1990-2006

It is a mistake to attribute too much of the rising urbanization of college-educated householders to the siren call of city lights, museums, and lakefront parks. That is because job location also strongly pulls along residential location (and vice versa). Through a job channel, the rising importance of information exchange in the U.S. economy may be the second vital large force that may be reviving central cities. New ideas, their dissemination, and the coordination of a complex worldwide economy have come to dominate economic output in developed nations; therefore, the siting of jobs and meetings of workers in dense configurations, some have argued, augments productivity and value generation. Central city location of work has become more desirable, which has pulled some jobs back toward the center of metropolitan regions.

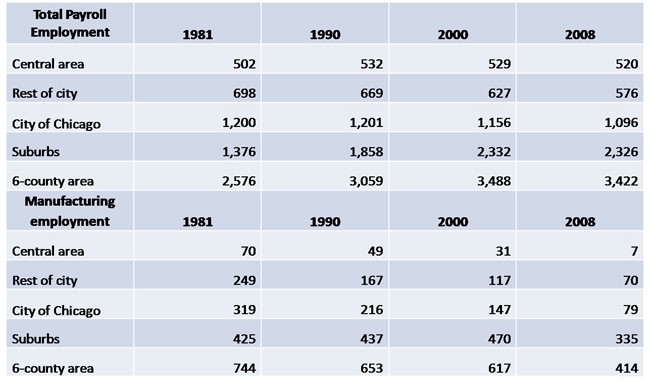

There is some evidence of this renewed role of central cities. At the same time that many central cities have shed some types of routine production jobs, gains have been made in occupations and industries that are steeped in workers who engage in information exchange and interaction. While the City of Chicago has been shedding manufacturing jobs—one of its historic mainstays—it has largely replaced such jobs with those in nonmanufacturing sectors. As shown below, city job losses are largely accounted for by the manufacturing sector alone; in fact, the city has experienced overall growth in employment net of manufacturing. More specifically, (not shown) over the period from 1991-2002, central city Chicago realized strong job gains in such industry sectors as business services (+34.4 percent), securities and commodities brokers (+61.8 percent), educational services (+25.1 percent), and engineering and management services (+13.6 percent).3

3. "Private sector employment (thousands) Chicago metropolitan area

Source: Illinois Department of Employment Security, Where Workers Work, (various issues).

In our recent investigation of household preferences for city versus suburban residence in the Chicago metropolitan area, we account for the proximity of households to their place of work. Once we statistically account for those city residents who also have found employment in the city, our estimates of the importance of educational attainment on household location in the city are somewhat smaller than we originally estimated. More importantly, “place of work” statistically explains much of the central city residential location decision. For this reason, we should not put too much emphasis on the importance of household amenities to central city living, nor perhaps should policymakers; jobs and job-attracting features continue to be important.

At this point, not much is known about the extent to which the changing economic structure of central cities is actually generating new jobs in related fields and transforming economic bases. And so, leaders and analysts in other Great Lakes cities are looking at the Chicago experience for insights as Chicago pursues policies to refashion itself as a “global city,” in both its residential amenities and in its attractiveness to highly skilled service industries that trade in world markets. Research initiatives that can discern the importance of the city as a job location from a residential location will be especially helpful to city mayors and other policy makers.

Footnotes

1 Cities with elastic boundaries—namely, Columbus, Ohio, and Indianapolis, Indiana—are excluded.

2 Not all of these gains reflect shifting preferences toward the city. Gains in overall educational attainment of the general population, especially young adults, enlarged the population of those adults that were, in turn, more likely to choose urban residence.

3 See U.S. Dept. of HUD, SOCDS County Business Patterns Special Data Extracts, available online.