State-local Debt and Unfunded Employee Benefits

A combination of events surrounding the recent recession have left many state and local governments with gaping budgetary holes. A recent report by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that states face a combined budget deficit of $375 billion for fiscal years 2010 and 2011.

Rather than raise taxes and cut spending cuts sufficiently, some governments, including Illinois, continue to add to their debt obligations to pay for current operations and debt service.

Widening deficits and mounting debt raise concerns that state and local governments will become seriously strained in meeting debt obligations and servicing their debt. If so, disruptive cuts to public services or punitive spikes in tax rates will likely take place at some future crisis point. Such sudden and possibly ill-considered corrective measures are not likely to help the cause of economic growth and development. Even before a crisis develops, a large debt overhang means uncertainty in the minds of would-be investors and in-migrants to the region as to how the obligations will eventually be paid down and, more specifically, uncertainty regarding which taxpayers will be impacted.

To be sure, not all debt accumulation diminishes a government’s capacity to repay its obligations or to finance public services. State–local government debt issuance often finances long-lived assets such as roads, school buildings, airports, and convention centers that are expected to pay for themselves, either directly through revenue streams such as highway tolls or other user fees, or indirectly by increasing economic growth and productivity of the local economy. However, to achieve such ends, judicious choices among alternative investments must be made; debt-financing of current consumption must be avoided.

The U.S. Census Bureau systematically gathers information on the outstanding debt of all state and local governments. The table below reports the Census data for the latest year available, 2007. All state and local governments reported debt outstanding of $2.4 trillion for fiscal years ending in 2007.

1. Combined state and local debt in 2007

In the table above, long-term debt overwhelms short-term debt outstanding. In theory, long-term debt may be preferred since the borrower has more time flexibility in meeting the ultimate re-payment of principal. However, the long-term option of repaying principal on public debt may make it less visible to the electorate who must monitoring borrowing and spending by elected officials.

In examining overall debt of state and local governments in Seventh District states—both short- and long-term combined, debt levels are generally seen to vary by size. To standardize, we divide debt outstanding by each state’s gross state product (GSP; see last column). GSP measures the total production value of goods and services from all sectors within a state for the year. It is equivalent to gross domestic product (GDP) for the national economy. By standardizing debt by the size of the state’s economy, we may reflect the state’s ability to repay debt by taxing productive activity.1

By this measure, all Seventh District states save Iowa would seem to be straining their debt-issuance capability compared with the national average. However, the measure is imperfect in several ways. For one, debt that is issued in fast-growing states may be financing infrastructure that will be needed for tomorrow’s (larger) population. It follows that tomorrow’s economy will be larger in these states too and provide greater potential for repaying today’s outstanding debt. However, Midwestern states have not been growing rapidly at all, so it seems unlikely they will grow their way out of debt.

The Census measure of debt outstanding also excludes an important category of debt that is thought to be potentially pernicious. In addition to the explicit debt illustrated above, which is issued through government bonds, state and local governments often accumulate non-bonded liabilities for pension and retiree health care. In the case of pensions, both governments and employees typically contribute to dedicated funds which are calculated to meet retiree payouts2. But state and local governments can choose to defer the funding of their full obligations to meet future pension and retiree health benefits (OPEBs) of today’s public employees and retirees. And unlike borrowing to finance long-lived infrastructure, such obligations reflect public services consumed today or in the past that will be paid out in the future. Accordingly, unless the state or local economy grows robustly of its own accord, such debts may grow sufficiently large to cause fiscal strains and stresses in future years.

Even before the recent recession, some governments had accumulated significant unfunded pension and retiree health care debt obligations (OPEBs). These are estimated in a recent a study by the Pew Foundation. The Pew report takes a conservative approach in producing these estimates. Excluded are the unfunded obligations for public employee pensions and OBEPs of local governments. Such local government plans can be very sizable, and the state versus local split varies by state.

As shown below, the Pew study reports that state governments had compiled an estimated $731 billion in such debt as of 2008. Measured as a claim on the U.S. GDP for 2008, state government debt represented just over 5 percent of GSP (last column, author’s estimates). Among District states, both Illinois and Michigan debt of this variety exceeded national averages by wide margins.

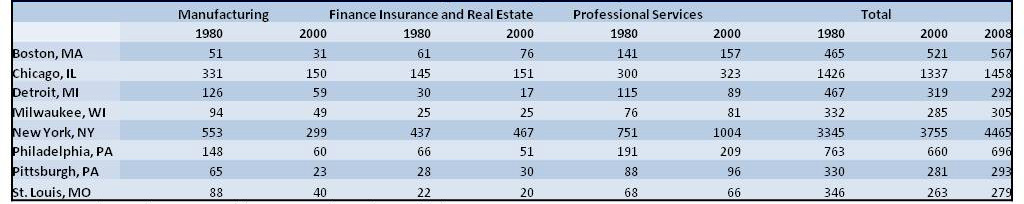

2. Jobs by place of work (in thousands)

The ability of state and local governments to redeem debt obligations is difficult to evaluate, even in the best of circumstances. Much as with private debt issuance, such evaluation requires careful scrutiny as to the purposes to which debt proceeds are used; the question being whether these purposes will pay dividends in the future3 or not. While inherently valuable, pension and other obligations for today’s or yesterday’s public employee services often have no such future dividends. Accordingly, state and local governments should exercise caution in deferring funding of these obligations. So, too, in their role as watchdogs of the ongoing decision making of elected officials, citizens and the electorate should carefully consider the full price of expanding public services, including pensions and OPEBs.

Footnotes

1 Not all product or wealth of a state can be readily reached by the tax or revenue system in place. For this reason, other measures of capacity may account for the “reachable” tax base under existing tax and revenue statutes and arrangements.

2 In addition to being nonbonded, the legal obligation to meet pension payout expectations may differ from state to state.

3 In contrast, government-funded educational services may enhance the productivity and income streams of future workers who remain in the state, some part of which may be taxed to redeem pension obligations incurred in the past.