Reshoring discussion

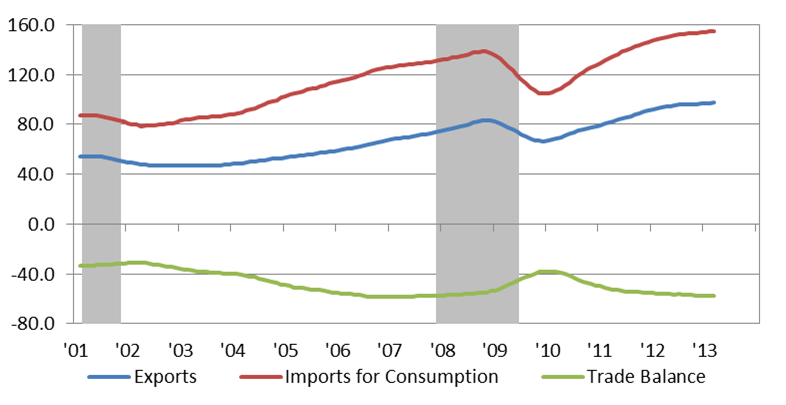

Robert Solow, an accomplished economist, once said that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”1 Similarly, the reshoring of manufacturing activities to the U.S. has been highly touted over the past two years, even though the evidence for it has been scarce. As skeptical analysts and journalists alike have indicated, if reshoring were taking place on a large scale, we would expect to see improvements in the U.S. balance of trade in manufactured goods with the rest of the world.2 Imports of manufactured goods would be waning and/or exports would be rising rapidly. On the contrary, the U.S. balance of payments in manufactured goods shows that little progress has been made in this regard since the years preceding the Great Recession (below).3

1. Monthly manufacturing trade balance in $billions F.A.S. value, Jan '01 to Feb '13 (12MMA)

Still, despite the lack of aggregate macroeconomic evidence to date, there appear to be legitimate prospects for the reshoring of manufacturing activities because of ongoing shifts in the underlying competitive conditions that favor manufacturing production on U.S. soil.

At our recent conference held in Detroit, encouraging and somewhat mixed prospects for re-shoring were presented for a wide spectrum of domestic manufacturing, as well as for two specific industries—chemicals and automotive.

Presenting the broad case for the reshoring of manufacturing activities, Justin Rose of The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), partly drew from a recent report called “Made in America, again.” According to Rose’s presentation, the U.S. share of world manufacturing has remained steady over the past 40 years, and the U.S. still makes over 70% of the manufactured goods it consumes—two facts that may be surprising for some to learn. China has emerged as a chief manufacturing competitor to the U.S. because of its low wages. Yet, on a productivity-adjusted basis, U.S. manufacturing wages have become more competitive with China’s since 2005, said Rose. And in terms of productivity-adjusted wages in manufacturing, the U.S. has a distinct advantage over many developed countries, including Germany, France, Italy, the UK, and Japan, because of its relatively less regulated labor market.

Rose noted that BCG has identified seven manufacturing subsectors that are close to a “tipping point” for reshoring. Further reductions in labor and logistics costs for the U.S. (or further increases in these costs for its competitors) may bring back to American shores a significant amount of manufacturing activity in the following industries: computing and electronics, machinery, electrical equipment/appliances, transportation equipment, plastics and rubber, chemicals, and primary metals. If a significant portion of these seven industries’ manufacturing activity were to return to the U.S., the result would be a gain of approximately $200 million in annual manufacturing output, said Rose.

Of these specific industries identified by BCG, the chemical industry may be the most likely to bring back the bulk of its production to the U.S., according to Martha Gilchrist Moore, senior director of policy analysis and economics for the American Chemistry Council. At our recent Detroit conference, Moore pointed out that the chemical industry will benefit greatly from the enhanced production of natural gas and natural gas liquids that are now taking place in the U.S. The chemical industry is the largest natural-gas-consuming industry in the U.S., and the U.S. shale gas boom is possibly the most important energy development in the past 50 years. Shale gas production has been climbing rapidly since 2005, and now accounts for 30% of U.S. gas production. Along with the gains in “dry gas” production have come supplies of natural gas liquids. These liquids are used as important feedstocks to chemical production. All of these developments are changing the economics of global petrochemical production in favor of the U.S. such that domestic chemical production is expected to increase 7.8% annually through 2020. Having tallied the recent shale-gas-related announcements from the chemical industry, Moore reported that $72–$82 billion of chemical industry investment stemming from shale gas is expected over the next ten years, which will enhance the domestic production of key chemicals such as ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. Most of these investments are expected to take place along the U.S. Gulf Coast, but some important projects are slated for the Midwest.

The automotive industry is another manufacturing subsector that is on the move, as reported by Chicago Fed senior economist Thomas Klier at the conference and in a recent Chicago Fed Letter. However, the motor vehicle industry is on the move to Mexico rather than the U.S. (i.e., it’s reshoring its activities to another part of North America). Klier showed that Mexico has raised its share of North American light vehicle production from 6% in 1990 to 19% in 2012. The growth of light vehicle exports explains virtually all of the increase in Mexico’s light vehicle production over the last 25 years or so.4 Moreover, foreign domiciled vehicle producers are an integral part of Mexico’s motor vehicle industry. Last year the three largest producers there were – in order – Nissan, Volkswagen, and GM.

According to Klier, Mexico has become an attractive location in which to manufacture automobiles not only because of its low labor costs, but also because of improvements in its training and infrastructure, and salutary changes in its trade policy over the past two decades. The major changes in Mexico’s trade policy began in 1994, when Mexico, along with the U.S. and Canada, implemented the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—which opened Mexico’s market to its neighbors to the north while (temporarily) discouraging auto imports from outside of the NAFTA area. More trade barriers came down for Mexico since 1994; as of 2012, Mexico had signed free trade agreements with 44 countries.

At first blush, it would not seem that rising auto production in Mexico contributes at all to the reshoring of manufacturing activities to the U.S. Rather, it would appear that gains in auto production in Mexico simply divert production away from the U.S. (and its other NAFTA partner, Canada). However, over 37 percent of Mexico’s auto exports are destined outside of North American to Asia, Latin America, Europe and Africa. And since some of the embedded value within Mexico-produced vehicles comes from parts and design that originate in the from U.S., those enhanced exports of finished vehicles from Mexico does augment manufacturing activity to the north. Because NAFTA has helped integrate auto manufacturing activities across Mexico, Canada, and the U.S., gains in production in one of the three NAFTA nations can mean gains in production for the others.

Will evidence of large-scale reshoring ever emerge? The answers to the issues raised by re-shoring will not be settled for quite some time. Shifting patterns of global trade and technological change make for a murky geographic landscape. But at the very least, some of the shifts underway will be toward U.S. domiciles rather than away from them.

Footnotes

1 Robert Solow, 1987, “We’d better watch out,” New York Times Book Review, July 12, p. 6.

2 See, for example, Timothy Aeppel, 2013, “Signs of factory revival hard to spot,” Wall Street Journal, April 1, available by subscription here.

3 These figures represent total manufacturing as stated in nominal dollars. Further analysis from 2003 to date using data that cover specific industry sectors in 2005 chained dollars are similar, though with some sectoral differences. Two sectors have experience shrinking trade deficits: Industrial Supplies (including petro products), and Food, Feeds and Beverages. Three other sectors report widening trade deficits: Capital Goods Excluding Automotive, Automotive, and Consumer Goods Excluding Automotive.

4 Automotive exports from the U.S. have also been rising markedly, see Thomas Klier.