Even as housing markets have temporarily shut down across the U.S. during the Covid-19 pandemic, housing remains a key sector that contributes disproportionately to fluctuations in overall economic activity and that will likely play an important role as the economy reopens. Interest in this market among research economists and policymakers intensified after the exceptional boom and bust in housing between 2003 and 2008. In this Chicago Fed Letter, we describe research in Barlevy and Fisher (2020)1 that examined patterns in the kinds of mortgages homebuyers took out in different cities during this episode. Recently, some have argued that the same kinds of mortgages that were used in the hottest real estate markets back then were beginning to reappear before the pandemic broke out, at least in some markets. These types of mortgages may also be more appealing in the near term for households who find themselves financially constrained in the wake of the pandemic.

Our research relied on loan data for 240 cities compiled from nine of the ten top mortgage servicers, covering the period between the first quarter of 2003 and the fourth quarter of 2008. In line with previous empirical work, we confirmed that buyers in the nation’s hottest markets were far more likely than buyers in other locations to take out backloaded mortgages featuring low initial payments. Among the most popular of these loans were interest-only (IO) mortgages that ask borrowers to repay only interest charges for some initial period, typically three to ten years, before paying down any principal. We then showed that the share of IOs among first-lien mortgages in a city seemed to be a particularly distinguishing feature of cities with rapid house price growth during the boom period between 2003 and 2006. While the mortgages issued during this period varied across cities along various dimensions, including the share of mortgages made to subprime borrowers, the share of loans that were privately securitized, and the share of loans where the loan amount exceeded 80% of the home’s value, these other characteristics were not nearly as strongly correlated with house price growth as the share of IOs. Indeed, the use of IO mortgages is the feature that really stands out in the cities with the fastest house price growth during this period.

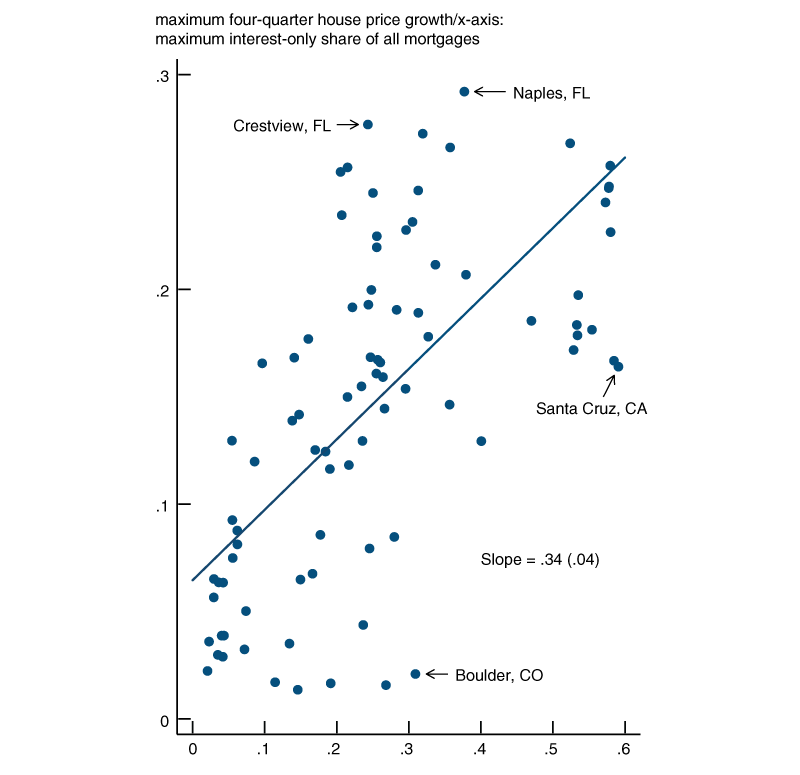

While the nationwide share of IO mortgages between 2003 and 2006 jumped from 2% to 19%, in hot markets like Phoenix the share exceeded 40% at its peak. Figure 1 shows a scatterplot of the maximum four-quarter house price gains over our sample against the peak IO share for cities with relatively inelastic housing supply due to geography and regulation, so that significant house price growth is possible. Cities with more elastic housing supply, which are not pictured, feature uniformly low house price growth and uniformly low IO use. Figure 1 illustrates that the extent to which the share of IOs took off is closely aligned with how quickly house prices grew.

1. Maximum house price gains versus peak interest-only mortgage share

Why were borrowers in cities with rapid house price growth attracted to IO mortgages?

Why were IO mortgages so popular in cities with hot housing markets, and what does their popularity tell us about the housing market at the time? If we knew why homebuyers tended to use IOs at high rates in these places, it might shed some insight on this episode.

Researchers have offered a number of explanations for the popularity of backloaded loans like IOs:

- Rising incomes. If buyers expected their incomes to rise, it might have made sense to structure payments to be low at the beginning and higher later in the life of the loan. According to this view, backloaded mortgages were popular in cities with high house price growth because those cities were also experiencing rapid income growth. This logic suggests the surge in house prices in those cities might have been driven by the same factors responsible for high income growth.

- Affordability. Low initial payments make houses less costly, at least during a loan’s early years. In cities where housing became expensive, borrowers may have relied on IOs to keep payments manageable, with the expectation of refinancing their loans later on. By this explanation, backloaded loans were a response to, as opposed to a cause of, rising prices.

- Demographics. Younger households tend to be more mobile and face more expenses related to raising children. This would have made mortgages with low initial payments attractive to younger and more mobile households. According to this view, backloaded mortgages were more popular in cities with high house price growth because of the demographics of these cities.

We performed regression analyses to examine whether these factors can help account for the relationship between house price gains and IO use. Our statistical analysis showed that rising incomes, affordability concerns, and demographic differences can indeed account for a large share of the variation in IO use across cities. IOs were especially popular in cities where house prices were high relative to income. But cities with high prices are not necessarily those where prices rise rapidly. In some cities, house prices were high but not growing. In others, prices were low and rose quickly, but not to especially high levels. Although we find evidence that IOs were indeed more common in cities where houses were less affordable, where incomes grew faster, and with younger and more mobile populations, we also find that these were typically not the same cities in which house prices surged the most. IOs were popular in cities with rapid house price growth, even though these cities were not typically associated with features that would have been expected to make IOs attractive.

Some researchers have argued that the reason IOs were popular in cities with fast house price growth was that lenders were more willing to extend backloaded mortgages when they expected house prices to rise. Higher expected house price growth protects lenders against losses if borrowers are unable to repay their loans. However, finance theory suggests expected future price growth should be higher only if house prices are also expected to be more volatile: Expected returns are high only when there is more risk. For lenders to profit in these circumstances, they would need to recover enough profits if house prices rise to offset losses if they fall. As Gorton (2008)2 argues, one way lenders could secure such profits is to impose a prepayment penalty so they can collect fee income if prices rise and borrowers have an incentive to refinance their mortgage. Alternatively, they may charge borrowers a high interest rate and then use a prepayment penalty to discourage them from refinancing. Either way, lenders would only offer backloaded mortgages when they expect high price appreciation if they could impose prepayment penalties on borrowers. We found that prepayment penalties were indeed more common in cities with high IO usage. But these penalties were not especially prevalent in cities with rapid price growth, nor were they disproportionately imposed on IO mortgages. The fact that higher expected house price growth should have made lenders more willing to offer backloaded loans cannot explain why IOs were so popular in hot markets.

We then proposed a new explanation for why IOs might have been so popular in the cities where home prices rose most rapidly: speculation. If lenders cannot seize the borrower’s remaining income in case of default, as was and is true in certain U.S. states, individuals may find it profitable to speculate on housing, borrowing to buy housing and profiting if prices rise while knowing they can default and cut their losses if prices fall. Speculators following this strategy would have certainly found IOs attractive, since their losses if prices fell would have been smaller the less they paid down on the house they purchased.

The demand for housing from such speculators can push prices above the level homes would command based strictly on their use as residences. Speculators buy houses not because of their utility as places to live, but because of the profits they can reap if prices go up. They value a house for its upside potential and would be willing to buy houses even if they were overpriced. This observation is consistent with research such as DeFusco, Nathanson, and Zwick (2017),3 who found that cites with large house price gains also saw an increase in sales volume during the housing boom due to “flippers”—buyers who bought properties with the intention of selling and turned them over within two years of purchase.

IOs can benefit both speculative buyers and lenders

Speculative buyers obviously stand to benefit from an IO mortgage’s low initial payments, given that their losses if forced to default would be smaller the less equity they had accumulated in the house. While IOs shift losses to lenders, the latter might still be willing to offer such loans if they believed IO mortgages encouraged speculators to sell their homes quicker than they would otherwise. In a market where houses are overvalued, lenders are better off if properties are sold quickly before their prices fall, rather than if they continue to be held by speculators. In effect, lenders would offer IOs with low payments early on and high payments later on to encourage speculators to sell more quickly. According to this explanation, the popularity of IOs in cities with rapid house price growth is a sign of active speculation taking place in those markets.

We found suggestive evidence of speculation among borrowers using IOs during the housing boom. First, we found that the cities with the highest IO shares were in states where lenders did not have recourse, and speculation should have been more profitable. Second, we found that borrowers with IOs were twice as likely to sell their houses in response to price increases as borrowers with traditional mortgages. Similarly, IO borrowers were twice as likely to default in response to falling prices. These results are consistent with IO mortgages being used to finance speculation.

Lessons for policymakers

Our research suggests that traditional explanations for the popularity of IO mortgages can help explain why IOs were more popular in some cities than in others, but not why IOs were especially popular in cities where house prices grew rapidly. That is, we confirmed that IOs were indeed more common in cities where incomes grew or were expected to grow; where housing was expensive; where households tended to be younger and more mobile; and where lenders were offering the types of loans that were reasonable to make if house price growth was expected to be both higher and riskier than elsewhere. But we also found that house prices surged in a fair number of cities with limited income growth, relatively inexpensive housing, and older and less mobile populations, and IOs still proved popular in these cities. A potential explanation for why IOs were popular in these hot markets that we find some support for is speculation in those markets. Both lenders and borrowers might favor these contracts when agents are borrowing to speculate that house prices might continue to grow.

What are the takeaways from our research for policymakers who worry about speculation feeding rapid house price growth that can eventually lead to defaults? Our analysis suggests that an increase in IO loans in cities where there are no other obvious reasons for their popularity may reveal the incidence of such speculation. So evidence on the types of mortgages borrowers use and where those mortgages are growing in popularity may be informative on the extent of underlying speculation.

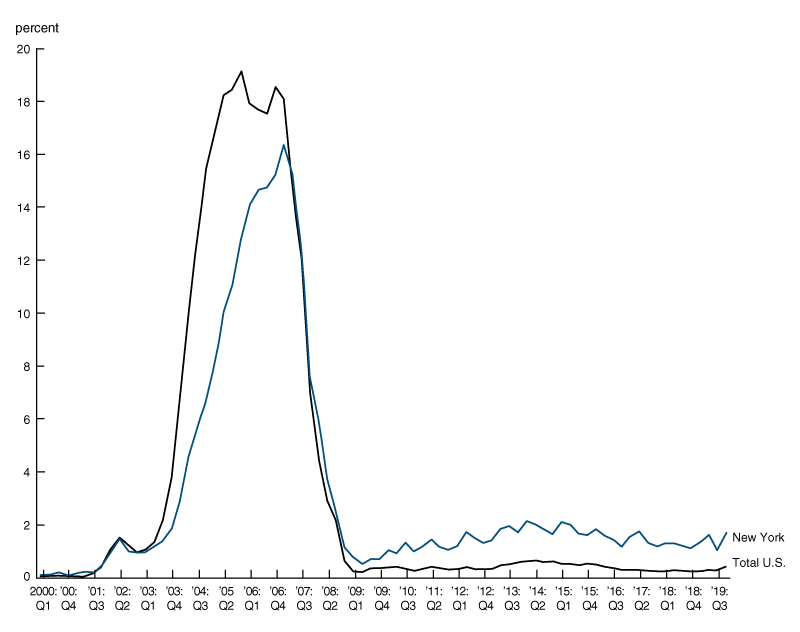

A 2018 New York Times article4 reported anecdotal evidence that IOs were regaining their popularity and argued this might herald the return of the speculative frenzy we saw back in the mid-2000s. When we extended the mortgage data we used in our research to 2019, however, we found that the share of IOs among originating mortgages for the U.S. as a whole in fact has remained below 1% since 2009. When we broke the data down to individual states, we did find a more pronounced revival in IO use in some areas, primarily in the Northeast. Figure 2 shows the share of IOs among all newly originating mortgages in the U.S., as well the share of IOs in newly originating mortgages in the state of New York, which had the highest IO share in 2019. But even the share of IOs in New York was only 1.6%, and IO use there since the financial crisis peaked back in 2014, just as it did for the nation as a whole. This does not quite suggest a rising trend in IO use.

2. Interest-only mortgages, share of originations

Even if there was a more pronounced rise in IO use in particular cities that is not apparent in the aggregate data, our analysis suggests caution in interpreting data on IO use and specifically warns against naively equating IOs with speculation. Beyond speculation, there are benign reasons for borrowers to use these mortgages, and the evidence suggests IOs may have been used in such ways. In principle, we could try to apply the same approach we do for the mid-2000s to gauge whether a rise in IOs can be explained by these benign factors or is more likely to be associated with speculation. For example, a rise in IOs in areas where lenders lack recourse would be more suggestive of speculation than a rise in areas where lenders have recourse. Yet we found that the places where IO use was highest in 2019 were all places where lenders have recourse, such as New York, Washington, DC, Connecticut, and New Jersey, and not places like California and Arizona where prices previously surged and where lenders have no recourse. By the same reasoning, a rise in IO in cities with little expected income growth would be a more alarming sign than a rise in cities with high expected income growth where IOs would be appealing for other reasons.

Since we found that IOs were popular among households whose income is low relative to house prices, households now suffering earnings losses due to shutdowns associated with the pandemic may find these types of mortgages appealing as they work to rebuild their incomes. To the extent that we do see a rise in these mortgages as the economy starts to recover, examining which households are the ones taking out these mortgages may allow policymakers to determine if such a resurgence is a sign of constrained households managing their payments more efficiently or a rise in speculation on what might happen to house prices in various areas as a result of the pandemic shock.

Finally, we caution that evidence of low IO use does not mean we can rest assured that speculation is not a concern. Our research suggests the appeal of IOs in markets with speculation is due to the way their payments are backloaded, which can be replicated in contracts that do not specify borrowers only pay interest early on in the life of a loan. IOs may be especially convenient vehicles for betting on rising home prices, but they are not the only alternative. If a market gets caught up in a speculative fever, other types of mortgages with backloaded payments could serve the purpose. This same reasoning suggests limiting or banning IO mortgages may not be effective in reining in speculation. An alternative way to curb speculation might be to limit nonrecourse lending that encourages speculation, although this would have to be balanced against any potential benefits from such lending.

Notes

1 Gadi Barlevy and Jonas D. M. Fisher, 2020, “Why were interest-only mortgages so popular during the U.S. housing boom?,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, working paper, No. 2010-12, revised January 9, 2020, available online.

2 Gary B. Gorton, 2008, “The Panic of 2007,” in Maintaining Stability in a Changing Financial System, proceedings of the Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, WY, pp. 131–262, available online.

3 Anthony A. DeFusco, Charles G. Nathanson, and Eric Zwick, 2017, “Speculative dynamics of prices and volume,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper, No. 23449, May. Crossref

4 Paul Sullivan, 2018, “Risky home loans are making a comeback. Are they right for you?,” New York Times, December 14, available online.