Monetary Policy: Slow Progress Toward Our Goals

A speech delivered on February 17, 2011, at the Rockford Chamber of Commerce Economic Outlook Luncheon in Rockford, Illinois.

It is my pleasure to be here in Rockford today to speak to you about my views on the progress of the recovery and on the course of monetary policy. I would like to thank Andrea (Ward) for that kind introduction and Harris Bank for working with the Chamber to sponsor this event.

Before offering my perspective on U.S. monetary policy, let me emphasize that the views that I am presenting today are my own and not necessarily those of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) or my other colleagues in the Federal Reserve System.

The U.S. economy is now in its second year of recovery following the deepest recession since the Great Depression. However, to a lot of folks, it still doesn’t feel all that real. Too many people remain unemployed, and too many businesses still haven’t returned to the operating rates they were running at before the recession. (Chart 1)

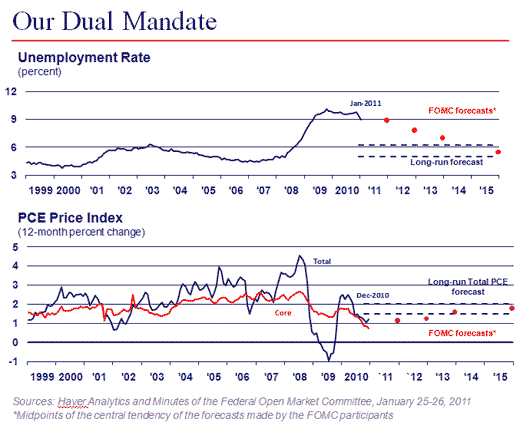

The Fed has a dual mandate from Congress to encourage conditions that foster both maximum employment and price stability. The charts on this slide report historical data and the FOMC’s current outlook for each of these objectives. Monetary policy decisions are made by the FOMC with the goal of achieving these objectives over time.

In normal times, this is done by appropriately setting the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate on overnight loans between banks. Voting members of the FOMC are Chairman Bernanke, members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and a rotating group of the 12 regional Fed presidents. I am currently a voting member of the FOMC.

With that background, let me briefly describe the current economic situation and then discuss the outlook. Over the course of the recession, U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) declined by more than 4 percent. Over 8.5 million jobs were lost, 1 the unemployment rate doubled to 10 percent and the household sector lost more than $13 trillion in wealth.

Aided by improvements in financial markets, accommodative monetary policy and fiscal stimulus, real GDP has been growing since mid-2009 and private employment has been increasing for almost a year. Overall though, the pace of recovery has been disappointing.

Early in the recovery, we had strong growth, boosted in part by the 2009 fiscal stimulus and the rebuilding of inventories drawn down during the recession. With the effects of these factors winding down, output growth moderated in the second and third quarters of last year. More recent data have been coming in stronger. That’s encouraging. But, as I will discuss shortly, closing the existing large resource gaps within a reasonable period of time requires a marked and sustained pickup in growth.

To be sure, there are many bright spots on the horizon. Looking ahead, there is an increased sense of optimism among virtually all economic forecasters. Some of the caution that has been holding back household and business spending is abating. Consumer spending, which accounts for roughly two-thirds of GDP, improved steadily throughout 2010 and increased at an annual rate of 4.4 percent last quarter.

While growth in business investment in equipment and software slowed down a bit last quarter, new orders for capital goods and surveys of purchasing managers point to further strengthening this year. Furthermore, the passage of the new stimulus package should boost paychecks and encourage businesses to invest in equipment.

The continued improvements in overall financial market conditions should provide additional support to consumer and business spending and investment, and growth abroad should help improve U.S. exports. Tempering these positive developments are the continued weakness in the housing market, state and local budgetary concerns and still somewhat restrictive credit terms for some borrowers.

The minutes of the January FOMC meeting — which were released yesterday — provide a perspective on the views of the participants on the Committee, including a summary of our economic forecasts. These predict output growth to strengthen further over the next three years: The central tendency of our forecasts is for real GDP growth to increase from a range of 3.4 and 3.9 percent this year to between 3.7 and 4.6 percent in 2013.

However, let’s not congratulate ourselves just yet: Even 4 percent is only moderately higher than the growth rate of potential output and thus represents a relatively muted recovery given the severity of the recession. In addition, this growth forecast is not strong enough to reduce unemployment very rapidly within a reasonable timeframe. As you can see on the chart, FOMC participants anticipate the unemployment rate being in the range of 6.8 to 7.2 percent at the end of 2013 — still above most estimates of what we would see in a healthy economy. I should note that these forecasts were made before last month’s data were published showing a four-tenths of a percentage point drop in the unemployment rate in January. But those data don’t change the fundamental message: We still have a long road ahead before we return to full utilization of the economy’s productive capacity and meet this piece of our policy goals.

The arithmetic is daunting. Employment now stands about 7.7 million below its peak three years ago as we entered the recession. The economy would have to generate over 210,000 new jobs per month for the next three years to make up for just these employment losses alone — and that doesn’t even cover any growth in the labor force (which is just under 1 percent per year). To date, job growth has been disappointing: On average, only about 80,000 new jobs were created monthly over the past three months. And looking forward, private forecasters expect average monthly job gains over the coming year of about 190,000. Although these improvements are welcome, the arithmetic implies only slow progress in returning to previous levels of employment. The chart of the unemployment rate captures this unfortunate reality.

Let me turn now to a discussion of the price stability element of our dual mandate, which is addressed in the bottom chart of the slide. From my vantage point, we haven’t done well on this dimension either. Inflation is measured as the growth in prices for a broad basket of goods and services. The Federal Open Market Committee considers a wide variety of such measures when gauging inflation and evaluating the appropriate stance of monetary policy. In general, we tend to focus on core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation, which removes the volatile food and energy components. Being free of this volatility makes the core measure a better indicator of broad underlying inflation trends — and therefore a better guide of where inflation is heading.

Most of us on the Federal Open Market Committee have said that a PCE inflation rate of about 2 percent is consistent with our price stability mandate. Yet, core inflation has been running well below this 2 percent rate for about two years. It has been roughly three-quarters of a percent for the past several months, and the FOMC forecasts have it reaching our mandate-consistent range only by the end of 2013. And my own assessment is that inflation will be lower than this path.

But wait. This seems like an unusual — and unpopular — viewpoint. With all the news about rising prices of crude oil, crops and other commodities over the past several months, you might reasonably wonder why I judge inflation to be too low. After all, I often hear people say, “Aren’t all prices really going up more than these inflation numbers say?”

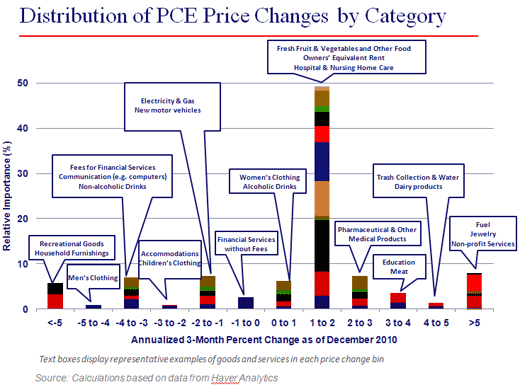

Let me explain. The broad PCE index is a weighted average of the prices paid for various goods and services. (Chart 2) The total index has risen at a three-month annual rate of 2.4 percent. True, gasoline prices have jumped over that period. But, on average, fuel accounts for only about 3.6 percent of expenditures. And despite the jump in meat and dairy prices, overall food prices have gone up only about 1-1/2 percent over the past 3 months (annual rate). In addition, the prices of many everyday categories of expenditures have increased very little or even have declined some.

Let me highlight a few. The price of a new car has actually declined at a three-month annual rate of 1.8 percent. Although cotton prices rose sharply in the second half of 2010, prices for men’s apparel actually fell over 4 percent and women’s clothing prices rose by less than 1 percent over the past three months (annual rate).

In fact, over 80 percent of what consumers spend their money on increased at an annual rate of 2 percent or less over the past three months.

Furthermore, when contemplating the inflation numbers, quality improvements are important to keep in mind. I am reminded of a comment once made by former Fed Governor Ed Gramlich that illustrates this point.2 Let's say someone gave you $10,000 and a choice of purchasing whatever you wanted out of one of two catalogs. One catalog has today’s goods at today’s prices. The other catalog is five years old. It has only goods that were available five years ago at those prices. Which would you choose? If you select from the older catalog, prices for most items would certainly be lower, but so would the selection of goods and the number and quality of their features. Would you prefer a five-year-old computer at five-year-old prices, or a 2011 computer that costs a bit more but has many more bells and whistles?

Indeed, the prices of many popular items have fallen. Five years ago a 60-inch HDTV cost $6,000. The current, much more sophisticated model, costs only $1,500. The iPad had yet to be invented and smartphones were primitive and pricey. For me the answer is pretty clear — I’d take today’s catalog. And, appropriately so, statisticians try to incorporate such new and improved items into our price indexes such as the PCE data I just showed you.

Prices that are falling because of improvements in technology are not a concern. But undershooting our overall inflation target because the economy is growing significantly below its potential is costly. Many people took on debt obligations two or three years ago, when they expected inflation would be nearer the 2 percent rate, which is approximately our price stability objective.

As such, the real burden of this debt is unexpectedly higher. Realigning inflation with these prior expectations — which were presumably held by both borrowers and lenders — would therefore be beneficial.

Another anecdote also illustrates an important point about inflation. Many years ago when I was a graduate student living on a tight budget, my wife, Ann and I were at a local grocery store picking up a few staples like peanut butter, bread and beer. At the checkout counter, we had a bit of sticker shock. Ann said to the teenager at the cash register, “Hey, this macaroni and cheese used to be four for a dollar, and now it’s 59 cents apiece!” Without looking up, the clerk said, “Yeah. And back then you were probably earning only $1 an hour, ma’am." Wow! That’s an A+ in Econ 101.

The link between wages and prices that this young cashier so clearly grasped suggests that unexpectedly low inflation can be costly in other ways as well. Businesses determine current hiring needs in anticipation of future revenues. Lower-than-expected product prices reduce revenues. If they persist and wages do not fall, then too-low prices increase real labor costs — that is, the cost of hiring a worker relative to the value of his/her output. Higher real labor costs reduce the incentive for hiring and may even generate layoffs. Again, validating businesses’ expectations of appropriate inflation would eliminate this source of negative feedback.

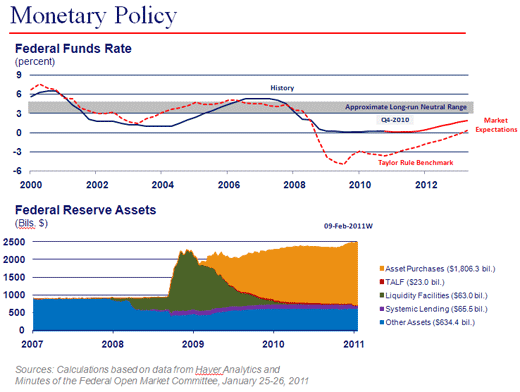

Now that I have set the stage, let me turn to my views on future monetary policy. (Chart 3) As I noted earlier, the Federal Reserve’s actions are driven by our dual mandate: We set policies to help foster both maximum sustainable employment and price stability. The current settings of U.S. monetary policy are intended to better achieve these mandates over time.

To put it bluntly, with unemployment too high and inflation too low — and both forecasted to stay that way over the next two years — we have missed on both of our policy objectives. There is currently no policy conflict between improving the employment and inflation outcomes. This leads me to conclude that accommodative monetary policy continues to be beneficial for achieving each of these goals.

To foster a return of economic conditions consistent with our dual mandate, we still need to keep short-term nominal policy rates low for an extended period. The FOMC’s policy statements have been very clear on this and have included this characterization for the federal funds rate since March 2009. In addition to directly influencing longer maturity interest rates, our recently expanded program of large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) plays an important and useful communications role.

It clearly demonstrates the FOMC’s commitment to keeping the federal funds rate extraordinarily low for an extended period of time. Although long-term inflation expectations — those five to ten years out — are not too far from our informal 2 percent target, current overall inflation is near 1 percent, and private forecasters generally expect it to run under 2 percent for the next couple of years.

So, all else being equal, bringing expectations of inflation back more quickly to 2 percent could translate into a helpful decline in real short-term interest rates. Economists believe that real interest rates are important determinants of economic decisions. That is because they adjust for the change in purchasing power between the time the borrower takes out the loan and the time he or she pays back the interest. So raising short term inflation expectations would be a modest but helpful step in realizing a more accommodative policy stance. Furthermore, with inflation below target, creating expectations of appropriately higher inflation in the short term is consistent with our price stability objective.

Of course, at some point the outlook for inflation will signal the appropriate time to remove policy accommodation. And should our strategy prove to be a little too successful and inflation rise faster than we expect, we have the tools to tighten quickly as needed.

Let me conclude with a final thought on the importance of communicating the Fed’s objectives clearly. Ambiguity in our message can undermine our ability to achieve our goals. We can make our existing tools more effective by explicitly stating our objectives and the likely course of future policy that would achieve them. I hope that my remarks here today have helped explain the issues we face and the complexities of implementing monetary policy to address them.

Although it will take time for monetary policy to succeed in reaching our goals, I am optimistic that we are moving forward in the right direction.

Thank you. I look forward to taking your questions.

Notes

1 This relationship is often referred to as the “Beveridge curve.”