Chicago Fed History: 1907-1914

The United States anticipated a prosperous year in 1907. The country was on its way to becoming the leading industrial nation in the world. The future looked bright.

Optimism was also strong in the Midwest. The Chicago Tribune noted that 1906 had been the most prosperous year ever for the city, and confidently predicted that the volume of business would be even greater in 1907.1

For most of 1907, these predictions generally held true. By March, however, bankers were already concerned about their inability to meet the financial demands of the booming economy. James B. Forgan, president of First National Bank of Chicago and later a director of the Chicago Reserve Bank, wrote: "Money is scarce all over...the pressure on us has been so extraordinary...I am in daily terror of something giving way under the strain."2

Eventually, something did give way. In October, the scarcity of money led to a panic in New York that spread through the rest of the country, Chicago's banks followed the lead of New York and suspended currency payments. As might be expected, depositors were angry. One irate letter to Forgan, signed only "A Small Depositor," stated that "unless the banks shall resume currency payments...so as to restore some feeling of confidence among the masses, there are apt to be such scenes of riot and bloodshed in this city as Chicago has not seen..."3

Throughout the country the banking system ground to a halt. In five states, banks were closed by order of the governor, and every state was forced to issue some form of emergency currency. 4 Eventually, the panic was halted through the efforts of J.P. Morgan and other leading bankers, but the damage had been done.

The panic, which occurred in the midst of general prosperity, illustrated one indisputable fact. The U.S. banking system was not meeting the financial needs of the country. The system's shortcomings included two basic problems — an inelastic currency and immobile reserves. The supply of national bank note currency, which was tied to government bonds, changed in response to the bond market rather than the needs of American business. In addition, bank reserves were scattered throughout the country — at a total of 50 different cities. Thus, even when there were enough reserves, it was difficult to move the money where it was most needed.

Striking a Balance

It was generally agreed that some form of central bank was needed. The controversy centered on how to structure the central bank. On one side the Progressive movement, which generally represented small businesses and the small town and farm population, was suspicious of concentrating too much power in the hands of bankers. Conservatives, representing the most powerful business and banking groups of the large Eastern cities, insisted on the need to avoid political interference in central banking.

The first attempt to solve the problem, the Aldrich Plan, was rejected as too conservative. In 1912, Representative Carter Glass of Virginia initiated a second attempt. Working with Glass was H. Parker Willis, a former professor of economics who served as advisor to the House Committee on Banking and Finance. Glass and Willis worked through most of the year and finished a draft just prior to Woodrow Wilson's election as president in November 1912.

To their plan for a system of regional Reserve Banks, Wilson added an important balancing feature — a central board to coordinate the work of the regional banks. The central board, a public agency, would be appointed by the President and approved by the Senate. To supply the elastic currency required by the economy, the central bank would rediscount bank notes and issue a new national currency — Federal Reserve notes. National banks would be required to become members of the Federal Reserve System, while banks chartered by the state would have the option of not joining.

After months of effort and compromising, the bill was passed by Congress on December 23, 1913. The U.S. had a central bank.

Although many bankers had opposed the Federal Reserve Act, especially those in Chicago, the majority were resigned, if not enthused, about the new legislation. One prominent merchant in Chicago wrote, "During the past week, I have heard a number of bankers and business men discuss [the Act], and there seemed to be a unanimity of opinion that, while the act is not an ideal one,.it is a great improvement upon the plan under which we are now working...it should be accepted in the hope...that the wrinkles, as they manifest themselves, will be ironed out by future legislation.5

Perhaps one of the reasons the Act was palatable for many was its vagueness on certain key issues. Regarding the number of Reserve Banks, the Act called for no fewer than eight and no more than 12. The question of each Bank's territory was left unanswered. An Organization Committee consisting of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of the Treasury was given the unenviable task of resolving these issues.

The Challenge of Creating Districts

When the Committee visited Chicago as part of a nationwide tour, there was little doubt that the city would have a Reserve Bank. Instead, the debate centered on the territory to be included in the Chicago Bank's district. Typically the Committee had encountered fairly partisan testimony, and Chicago was no exception. Presenting the case for Chicago bankers, J.B. Forgan advocated putting all of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin — and even parts of Nebraska, Minnesota and Ohio — in the Chicago Reserve district.

Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo, who earlier had listened to New York lay claim to nearly half of the country's banking resources, noted that there would be very little left for the other Fed Banks if New York and Chicago were accommodated. Forgan, never shy in presenting his view, responded: "That is the difficult problem that you gentlemen have got to solve...From one point of view, you know, if we are just going to look upon it territorially we are really the center and New York is on the circumference of the circle."6

After the Organization Committee left Chicago, interest in the new central banking system quickly waned. There was little excitement in the Midwest when it was announced that there would be twelve districts and that the Chicago Bank's territory would consist of northern Illinois and Indiana, southern Wisconsin. all of Iowa and the lower peninsula of Michigan. This decision was supported by a poll in which 714 of the 861 banks in that area chose Chicago as its preferred Reserve Bank location.7 (The only change in the Bank's district since then occurred when northern Wisconsin banks assigned to the Minneapolis Reserve Bank's territory petitioned to be moved to the Chicago district. The Federal Reserve Board allowed banks in 25 Wisconsin counties to shift to the Seventh District in October 1916.)

Opening Bell

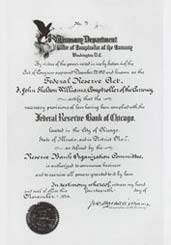

Chicago Fed's organization certificate, November 1914.

The organization of the Chicago Reserve Bank proceeded quickly. Soon after the Organization Committee announced its decision, representatives from five Seventh District banks gathered on May 18, 1914, for the formal signing of the Chicago Fed's organization certificate. As specified in the Federal Reserve Act, six of the Bank's nine directors were elected by member banks. The Federal Reserve Board appointed the other three directors, including C. H. Bosworth who served as chairman of the board and federal reserve agent.

The appointment was in keeping with the Federal Reserve Act, which specified two positions — governor as well as chairman of the board and federal reserve agent. The framers of the Act seem to have intended that the federal reserve agent serve as the Bank's chief executive officer. A majority of the Bank's directors, however, decided that the governor, who would be their own appointee, should assume that role. The Federal Reserve agent, in the words of one of the directors, was to "have a minor position."8

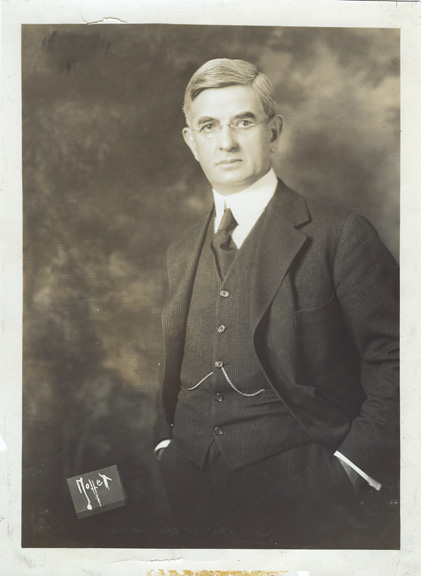

James B. McDougal, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago's first governor.

Having decided on this matter, the directors selected James B. McDougal as the Bank's first governor. (In 1935, the title of governor was changed to president.) The choice "was greeted with universal approval," according to a local news report.9 As head examiner for the Chicago Clearing House for the past eight years, McDougal was well-acquainted with Chicago bankers. He had also spent 14 years with a commercial bank in Peoria and worked as an examiner with the Comptroller of the Currency.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, along with the other 11 Fed Banks, opened for business on Monday, November 16, 1914. One of the Bank's original employees later described the scene: "After less then three weeks of preparation...some place to hang your hat and coat — a few desks and stools...the message from Washington [arrived], 'All ready — get set' and Governor McDougal's happy smile and hearty handshake and then, 'We're off' — the roar of flashlights to the click of the newspaper cameras..."10

While the Bank and its 41 employees were ready to carry out their appointed duties, exactly what these duties would be was to some extent unclear. The Bank's first annual report noted optimistically, if somewhat uncertainly, that the "various departments are now fully organized and equipped and in readiness for increased activities, whatever they may be."

1F. Cyril James, 1938, The Growth of Chicago Banks, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

2ibid.

3ibid.

4ibid.

5ibid.

6ibid.

7John A. Griswold, 1936, A History of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, St. Louis: John A. Griswold.

8James, op. cit.

9ibid.

10Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1919–1931, Among Ourselves, Chicago, Various Issues.