Chicago Fed History: 1915-1939

Following the relative excitement of the opening, the Chicago Fed spent its first few months feeling its way in its new role as a Reserve Bank. As specified in the Federal Reserve Act, the Bank issued Federal Reserve currency and rediscounted some bank notes. In general, however, the Bank was calm. Years later, the Bank's only switchboard operator reminisced of bringing sewing to work because there were only six calls a day.1 A more formal indication of the Bank's relatively calm operations is contained in the 1915 annual report, which notes that "Notwithstanding the relatively small demands...for either credit or currency...the system fully demonstrated its worth, inspiring confidence and banishing fear, and forestalling panic from the mere fact of its existence."

The Growth of Other Services

With its currency and rediscounting functions at a low ebb, the Bank focused on developing a check collection system — one of the responsibilities that fell under the vague category of "other purposes" in the preamble of the Federal Reserve Act. Throughout its history, the U.S. banking system had been hampered by an inefficient collection process. Although local clearinghouses operated efficiently in some large cities, much of the country was saddled with exchange fees and indirect routing designed to avoid these charges. Recognizing these flaws, the Federal Reserve Act gave the Fed authority to provide check-clearing services. A check collection plan faced one basic problem: Many bankers had come to depend on exchange fees as a regular source of income and were reluctant to make changes.

While the Chicago Fed offered limited clearing services on the first day it opened, it concentrated on developing an intra-district collection system in which checks would be accepted without an exchange fee, also known as "accepting at par." In April 1915, member banks were notified that a voluntary collection system would go into effect on June 10. Banks were free to join the system, or ignore it. In general, they chose to ignore it. During the one and only year of the voluntary operation, only 114 of the District's 980 member banks participated. The voluntary system had, in the words of the Bank's 1916 annual report, "proved unsatisfactory."

Having tried a voluntary approach, the Federal Reserve instituted a compulsory system for member banks in July 1916. All member banks were required to accept at par a check drawn upon themselves and presented for payment by a Fed Bank. To discourage exchange fees, the Fed Banks distributed a list of banks that accepted at par.

The effect of the new system was immediate. The Bank's check volumes rose from 8,900 items a month under the old system to 18,000 checks a day through the rest of 1916.2 The trend toward par collection received a boost in 1918 when the Fed Banks began offering collection services free of charge to all banks on the "par list." By 1920, the Bank's original seven-man Check Department had 350 employees processing 60 million checks annually. The number of District banks collecting at par grew quickly. Over 3,300 banks appeared on the par list in January 1918. Four years later, every bank in the District accepted at par. Nationwide, all but 1,755 of the country's 30,523 banks accepted at par in 1921.3

Through the rest of the 1920s, opposition began to build as opposing bankers fought par collection through the courts or state legislatures. In some cases, banks took more direct methods such as stamping on blank checks, "Not valid if presented through Federal Reserve."4 This resistance was mainly centered in the southern and western sections of the country. In the Seventh District, bankers generally accepted the plan, with some misgivings, as being good for business.5 In spite of some lingering resistance, par collection was established and eventually became standard practice.

The Fed Takes on U.S. Bonds

A poster encouraging the purchase of war bonds.

Having opened just three months after the outbreak of the war in Europe, the Chicago Fed did not have to wait long to assume its second major responsibility. When the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Reserve Banks were authorized to handle the financial operations associated with the war, including the sale of Liberty Bonds. The nationwide goal of the first Liberty Loan campaign was to sell $2 billion in bonds — a staggering amount of money at the time. According to Financing an Empire: History of Banking in Illinois, even the largest bankers were "stunned" and at first thought that "such a stupendous amount could never be raised."6

Nevertheless, the campaign began in earnest in the Seventh District. Additional quarters were rented by the Bank, committees of leading citizens were appointed, and publicity efforts began. The initial response, however, was not promising. To the people in the Seventh District, the war must have seemed a distant and not very real event. Noting the lack of interest, the Chicago Tribune fretted that the American people must be made to realize "that they are not in normal conditions, but are going into the ordeal by fire." The newspaper added that Americans "must meet the test with their money and with their bodies. The nation wants, now, the people's money. It is a test of patriotism." Efforts intensified: A great parade of bond salesmen marched through the city, and the "Four Minute Men" — a small army of speakers who gave short talks on bonds — were dispatched wherever an audience could be gathered.

On June 10, with only five days left in the campaign, the District had subscribed slightly more than half of its $298 million quota. In response, the city of Chicago ordered that churches and schools ring their bells every day to remind citizens of the cause. Finally, in the last few days of the campaign, enthusiasm began to build and subscriptions rapidly increased. By June 15, the aggregate sales were $357 million and the District had easily exceeded its quota. Four more Liberty Loan campaigns were undertaken in the next two years. Bond sales for the District totaled $3.29 billion — the largest subscription per person in any of the Federal Reserve Districts. The Illinois portion of the District alone accounted for $1.45 billion, more than the country's total bonded debt in 1916.7

For the Chicago Fed, which was responsible for organizing the bond effort as well as processing the securities, the immediate impact of the Liberty Loan campaigns was tremendous. The war effort had a more important long-term effect, however. In the spring of 1915, the Fed Banks were in the blunt opinion of J.B. Forgan, "not of much benefit anywhere."8 The Liberty Loan campaign accelerated the Fed's integration into the banking system, and by October 1917 Forgan wrote, "You must get in the habit of believing and acting on the fact that your bank is part and parcel of the Federal Reserve System...The stronger the Federal Reserve banks are, the stronger will the [banking) system be."9

The Move to LaSalle and Jackson

Due to the sudden growth of its burgeoning check and fiscal agent duties, the Chicago Fed quickly found itself outgrowing its quarters. Initially the Bank opened for business with 41 employees on two floors in the Rector Building at Clark and Monroe. By 1919, the Bank's 1,200 employees were scattered throughout the Loop. In some cases stenographers had to cross the street from one building to another and climb three flights of stairs to take dictation. Other problems cropped up: One building was overrun with rats, and another had heating deficiencies. Years later, two of the Bank's original employees wrote of trying to keep warm by resorting to the Dickensian solution of wrapping currency sacks around their feet.10

It was clear that new quarters were needed. Accordingly, the Chicago Fed purchased a 165 x 160-foot lot on LaSalle Street extending from Quincy Street to Jackson Boulevard. The 1918 annual report noted that the property was not only "the most desirable site" in the city for the Bank's purposes, but was "acquired at an exceedingly low cost, the purchase price being $2,936,149."

Having purchased property, the Bank's directors hired the architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst and White to design the building. The firm, which later designed the Continental Bank Building across the street from the Chicago Fed, also built such Chicago landmarks as the Wrigley Building, the Civic Opera and the Merchandise Mart.

Beset by labor and material shortages, the project was delayed for several years. Construction was eventually completed in 1922 at a cost of $7 million. The 1920 annual report depicted the building as "classic in style, fully interpreted to harmonize with modern conditions." The report added that in "line with modern ideas very comprehensive arrangements have been included for the general welfare of the entire working staff. An assembly room, dining rooms, rest rooms...are some of the more important features."

And on to Detroit

As the Bank began planning a new building in Chicago, there was increasing interest in establishing a Branch in Detroit. Fed member banks in the lower peninsula of Michigan had to clear checks and obtain rediscounts through the Chicago Bank, a fairly inefficient process given the geography involved. Frustrated by these time delays, Michigan bankers met in Lansing in 1917 in an effort to build enthusiasm for locating a Branch in Detroit. As the second largest industrial area in the Seventh District, Detroit was a logical candidate, and the Chicago Fed board of directors voted in November 1917 to establish a Branch.

The Branch opened for business on March 18, 1918. The following year, the Bank's annual report stated that the Branch "justified in every way its creation." As expected, the Branch eliminated a delay of one or two days in check clearing, rediscounting and other operations. By 1920, the Branch began to exercise all of the functions of a Reserve Bank except for note issuance and a few minor tasks.

Having proved its worth in its World War I financing efforts, and with the check collection system well in hand, the Fed began to delve gingerly into the relatively unexplored terrain of monetary policy. Throughout the 1920s, the Federal Reserve moved toward increased centralization and coordination in monetary policy. The concept of 12 regional credit policies based on the needs of each district was slowly replaced by a coordinated policy that balanced the needs of each district.

Chicago Sets the Pace for Analysis

An important first step was in the area of research and statistical analysis. In the early 1900s, due in part to the advent of the federal corporate income tax, statistical information on business trends was becoming increasingly available. The Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC, and the Fed Banks began to sort and analyze the data, an effort pioneered by the Chicago Fed. In 1918, the Chicago Reserve Bank established the Statistical and Analytical Department to compile statistical information for the Federal Reserve Board and member banks. The Bank had already begun publishing Business Conditions, a monthly review of the Seventh District economy, in October 1917. Over the next few years, the Chicago Fed began collecting a condensed statement of condition from selected member banks and started a "Business Reporting Service" that gathered data from producers and merchants. As the Reserve Banks refined their research capabilities, the Federal Reserve had a prerequisite for a centralized policy — a flow of information from each section of the U.S. to incorporate into an overall policy.

As the Fed Banks increased their research efforts, they became increasingly aware of a potentially powerful new monetary policy tool — open market operations. When the System was created, rediscounting, or making loans to member banks, was the chief means of affecting credit. It was not until 1921, when the Reserve Banks began to buy and sell government securities to build their earnings, that the potential effect of open market operations was fully realized.

Crafting Monetary Policy for the Nation

In 1923, the Federal Reserve Board established the Federal Open Market Investment Committee comprised of the governors of the Chicago Fed and four other Reserve Banks. Operating under the supervision of the Board, the Committee was instructed to conduct operations "with the primary regard for the accommodation of commerce and business and to the effect of these purchases and sales on the general credit situation."

Even as open market operations became increasingly centralized, the role of the Reserve Banks in setting the discount rate was still unclear. Under the Federal Reserve Act, the Reserve Banks set the regional discount rate subject to the "review and determination" of the Federal Reserve Board.

Dissent with the Board

An early controversy involving the Chicago Reserve Bank highlighted the issue of the discount rate. The incident initially involved Chicago Reserve Bank Governor McDougal and Benjamin Strong, the head of the New York Reserve Bank. In 1927, Strong was leading an effort to reduce the discount rate. Strong's outlook was a global one — he favored an easy money policy to aid the European financial position. McDougal, traditionally a conservative in credit policies, opposed the move as did several other Reserve Banks. Strong wrote to McDougal in August 1927 exhorting the Chicago Bank to join a System-wide effort to ease credit. McDougal was not persuaded. In a letter to Strong, he wrote, "It is understood that the governing factor...is the international situation, and it seems to me that the desired result has already been attained through the reduction in your rate." As far as uniformity among the Reserve Banks was concerned, McDougal wrote, "up to the present time we are not convinced as to the necessity of having a uniform rate in all districts."

Strong replied, "My dear Mac: I have read that austere letter of yours...and after finishing it felt as though I were sitting in an unheated church in midwinter, somewhere in Alaska." According to Strong, lowering the discount rate "is neither a New York question nor a Chicago question nor a district question but a national question bearing upon our markets in Europe, consequently an international question."

Still, McDougal and the Bank's board held firm. The discussion erupted into a controversy when the Federal Reserve Board ordered the Bank to reduce its rate on September 6. The Board's action aroused bitter controversy within the System and a fair amount of publicity outside the System. Two of the strongest dissenters against the Board's action were Carter Glass and H. Parker Willis. Strong himself opposed the move and tried to prevent it.12 According to the New York Herald Tribune, the controversy centered on "the long smouldering question of whether in matters of fundamental policy the several regional reserve banks of the system are to be granted self determination. ..."

The Chicago Bank complied with the rate reduction, but also announced that it would seek an opinion from the U.S. Attorney General as to the legality of the Board's action. Later, however, the Bank had second thoughts, and the convenient resignation of one of the Board members supporting the forced discount rate reduction helped to ease the controversy. The issue was not resolved, but the trend toward centralization had received additional impetus.

Challenges on the Horizon

As the Federal Reserve refined its monetary policy efforts, the U.S. experienced a giddy period of industrial growth and high employment through most of the 1920s. In keeping with the confidence of the times, many felt that financial panics had become a thing of the past. As late as 1931, the Encyclopedia of Banking and Finance stated "this country is now thought to be panic proof."13 At the same time, many worried about the extremely high levels of speculative spending. In February 1929, the Federal Reserve Board, as part of its unsuccessful campaign to curtail speculation, decried the "excessive amounts of the country's credit absorbed in speculative security loans."14

Soon after that statement, the stock market began to sour. The plummeting market shook the confidence of the United States. In Chicago, the glum attitude was reflected on October 22 as a band marched up LaSalle Street to celebrate the laying of the cornerstone of the new Board of Trade Building. Many listeners, according to the Chicago Tribune, thought the band should have played a funeral dirge.15 On October 29, the stock market crashed. The Fed responded by easing credit through open market operations and reductions in the discount rate, a policy it continued through the first half of 1931.

Nevertheless, the economic decline continued. By mid-1931, a financial crisis abroad added momentum to the Depression. England abandoned the gold standard in September 1931, a move that shook the international financial community. Fears of dollar devaluation triggered a flow of gold out of the U.S. The Federal Reserve reacted in traditional central bank fashion by tightening credit, the classic method of slowing the flight of gold.

Contributing to the Fed's decision was a requirement of the Federal Reserve Act that gold or eligible paper provide backing for Federal Reserve currency. With eligible paper scarce, the need for gold as collateral increased. In addition, many simply thought that tighter credit was needed. Many commercial banks, understandably skittish after the events of the past two years, kept excess reserves as a cushion, a move that helped convince the Fed that some tightening was needed.16 In Chicago, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle reported that funds were so plentiful that bankers reversed their earlier pleas for liquidity and were in open revolt against the easy money policies of the Fed.17

The Great Depression

The tightening of credit, however, put increased pressure on the economy. The Depression deepened and unemployment rose to 11 million. The Seventh District reflected the nationwide trend. The Bank's annual report noted that "in 1931, as in the preceding year, the Seventh District shared in the world-wide decline in industrial and business activity." The dropping agricultural prices and "unusual number" of bank suspensions fueled the District's sharp decline.

Spurred by the economic problems, Congress passed the Glass – Steagall Act of 1932, which enabled the Fed to use government securities as backing for its notes. During the first nine months of 1932, the Reserve Banks bought an unprecedented $1 billion of securities, but this additional liquidity was quickly absorbed by the parched banking system.18

The economy continued to decline, and industrial activity reached a low point in July 1932. Banks began to feel extreme pressure. In addition to growing loan defaults, the country experienced a wave of currency hoarding. State and local governments began to announce bank holidays. In the Seventh District, a number of local holidays were announced in cities such as Rock Island, Illinois; Muscatine, Iowa; and Huntington, Indiana.19 The piecemeal approach to bank closings accelerated the deposit withdrawals.

As pressures increased, the two dominant banks in Detroit were facing collapse by February 1933. Chicago Fed Governor McDougal, leading commercial bankers, U.S. Treasury officials, representatives of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), and others met to try to resolve the crisis. After studying the banks' books, the RFC declined to provide the large loan necessary to keep the banks open. Private corporations also refused. With no solution in hand, the governor of Michigan declared a statewide bank holiday on Tuesday, February 14. The closing was a severe shock. During the rest of the week, the currency drain on the Chicago Fed was three times greater than for the same period in 1932.20

During the first three days of March panic reached a peak throughout the U.S. as bank customers withdrew huge amounts of deposits. On March 3, the evening before the inauguration of Franklin Roosevelt, the governors of Illinois and New York declared a bank holiday. The executive committee of the Chicago Fed's board of directors met at 10:30 p.m. that night and passed the resolution that the "Federal Reserve Board should urge upon the President of the United States that he immediately declare a bank holiday... in order to give the banks and the governmental authorities sufficient time and an opportunity to provide the necessary measures for the protection of the public interest..." The nation's banking system was effectively shut down.

Although a host of factors caused the banking collapse, many beyond the reach of the Federal Reserve, the fact remained that the Fed was unable to head off the very catastrophe it had been established to prevent. In addition to being hindered by out-of-date legislation, the Fed did not yet have a full understanding of the capabilities and responsibilities of a central bank. Throughout the crisis, the Federal Reserve's progress on the monetary policy learning curve was a step behind the sequence of events.

Roosevelt took quick action once he assumed office. Under the Emergency Banking Act of 1933, banks were reviewed by regulators and licensed to reopen if they were solvent. Confidence was restored and the crisis passed. The cost was high — bank suspensions soared in the early 1930s, reaching 4,000 in 1933. Approximately 30 percent of the suspensions were in the hard-hit Seventh District.21

Birth of the FOMC

With the banking crisis in hand, Congress took on the task of reforming the financial system. Banks were restricted from engaging in securities activities and prohibited from offering interest on demand deposits. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created to protect small depositors against loss. The Federal Reserve was given a powerful new monetary policy tool — the authority to change member banks' reserve requirements.

The Fed also received permanent authority to lend to member banks on the basis of "satisfactory" assets. Previously, the Fed was prevented from lending to institutions that did not have eligible paper to collateralize the loan. The legislation also capped the Federal Reserve's trend toward centralization by creating the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to conduct the System's open market operations. This committee, consisting of the Board and five Reserve Bank presidents, came to be the System's chief monetary policymaking body.

Despite the legislation and the New Deal efforts to stimulate spending, the downswing continued through the 1930s. It was not until preparations for World War II began that the country completely shook off the Depression. Although the Federal Reserve now had its monetary policy tools in hand, and a better understanding of how to use them, fiscal policy dominated the scene for the next ten years. As in 1917, a world war was to absorb the Fed's attention for the next several years.

Following the relative excitement of the opening, the Chicago Fed spent its first few months feeling its way in its new role as a Reserve Bank. As specified in the Federal Reserve Act, the Bank issued Federal Reserve currency and rediscounted some bank notes. In general, however, the Bank was calm. Years later, the Bank's only switchboard operator reminisced of bringing sewing to work because there were only six calls a day.1 A more formal indication of the Bank's relatively calm operations is contained in the 1915 annual report, which notes that "Notwithstanding the relatively small demands...for either credit or currency...the system fully demonstrated its worth, inspiring confidence and banishing fear, and forestalling panic from the mere fact of its existence."

The Growth of Other Services

With its currency and rediscounting functions at a low ebb, the Bank focused on developing a check collection system — one of the responsibilities that fell under the vague category of "other purposes" in the preamble of the Federal Reserve Act. Throughout its history, the U.S. banking system had been hampered by an inefficient collection process. Although local clearinghouses operated efficiently in some large cities, much of the country was saddled with exchange fees and indirect routing designed to avoid these charges. Recognizing these flaws, the Federal Reserve Act gave the Fed authority to provide check-clearing services. A check collection plan faced one basic problem: Many bankers had come to depend on exchange fees as a regular source of income and were reluctant to make changes.

While the Chicago Fed offered limited clearing services on the first day it opened, it concentrated on developing an intra-district collection system in which checks would be accepted without an exchange fee, also known as "accepting at par." In April 1915, member banks were notified that a voluntary collection system would go into effect on June 10. Banks were free to join the system, or ignore it. In general, they chose to ignore it. During the one and only year of the voluntary operation, only 114 of the District's 980 member banks participated. The voluntary system had, in the words of the Bank's 1916 annual report, "proved unsatisfactory."

Having tried a voluntary approach, the Federal Reserve instituted a compulsory system for member banks in July 1916. All member banks were required to accept at par a check drawn upon themselves and presented for payment by a Fed Bank. To discourage exchange fees, the Fed Banks distributed a list of banks that accepted at par.

The effect of the new system was immediate. The Bank's check volumes rose from 8,900 items a month under the old system to 18,000 checks a day through the rest of 1916.2 The trend toward par collection received a boost in 1918 when the Fed Banks began offering collection services free of charge to all banks on the "par list." By 1920, the Bank's original seven-man Check Department had 350 employees processing 60 million checks annually. The number of District banks collecting at par grew quickly. Over 3,300 banks appeared on the par list in January 1918. Four years later, every bank in the District accepted at par. Nationwide, all but 1,755 of the country's 30,523 banks accepted at par in 1921.3

Through the rest of the 1920s, opposition began to build as opposing bankers fought par collection through the courts or state legislatures. In some cases, banks took more direct methods such as stamping on blank checks, "Not valid if presented through Federal Reserve."4 This resistance was mainly centered in the southern and western sections of the country. In the Seventh District, bankers generally accepted the plan, with some misgivings, as being good for business.5 In spite of some lingering resistance, par collection was established and eventually became standard practice.

The Fed Takes on U.S. Bonds

A poster encouraging the purchase of war bonds.

Having opened just three months after the outbreak of the war in Europe, the Chicago Fed did not have to wait long to assume its second major responsibility. When the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Reserve Banks were authorized to handle the financial operations associated with the war, including the sale of Liberty Bonds. The nationwide goal of the first Liberty Loan campaign was to sell $2 billion in bonds — a staggering amount of money at the time. According to Financing an Empire: History of Banking in Illinois, even the largest bankers were "stunned" and at first thought that "such a stupendous amount could never be raised."6

Nevertheless, the campaign began in earnest in the Seventh District. Additional quarters were rented by the Bank, committees of leading citizens were appointed, and publicity efforts began. The initial response, however, was not promising. To the people in the Seventh District, the war must have seemed a distant and not very real event. Noting the lack of interest, the Chicago Tribune fretted that the American people must be made to realize "that they are not in normal conditions, but are going into the ordeal by fire." The newspaper added that Americans "must meet the test with their money and with their bodies. The nation wants, now, the people's money. It is a test of patriotism." Efforts intensified: A great parade of bond salesmen marched through the city, and the "Four Minute Men" — a small army of speakers who gave short talks on bonds — were dispatched wherever an audience could be gathered.

On June 10, with only five days left in the campaign, the District had subscribed slightly more than half of its $298 million quota. In response, the city of Chicago ordered that churches and schools ring their bells every day to remind citizens of the cause. Finally, in the last few days of the campaign, enthusiasm began to build and subscriptions rapidly increased. By June 15, the aggregate sales were $357 million and the District had easily exceeded its quota. Four more Liberty Loan campaigns were undertaken in the next two years. Bond sales for the District totaled $3.29 billion — the largest subscription per person in any of the Federal Reserve Districts. The Illinois portion of the District alone accounted for $1.45 billion, more than the country's total bonded debt in 1916.7

For the Chicago Fed, which was responsible for organizing the bond effort as well as processing the securities, the immediate impact of the Liberty Loan campaigns was tremendous. The war effort had a more important long-term effect, however. In the spring of 1915, the Fed Banks were in the blunt opinion of J.B. Forgan, "not of much benefit anywhere."8 The Liberty Loan campaign accelerated the Fed's integration into the banking system, and by October 1917 Forgan wrote, "You must get in the habit of believing and acting on the fact that your bank is part and parcel of the Federal Reserve System...The stronger the Federal Reserve banks are, the stronger will the [banking) system be."9

The Move to LaSalle and Jackson

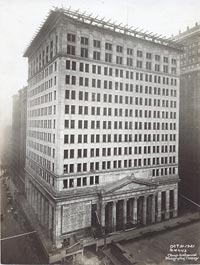

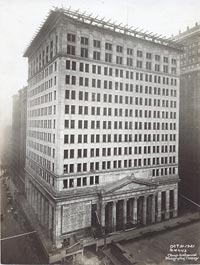

Due to the sudden growth of its burgeoning check and fiscal agent duties, the Chicago Fed quickly found itself outgrowing its quarters. Initially the Bank opened for business with 41 employees on two floors in the Rector Building at Clark and Monroe. By 1919, the Bank's 1,200 employees were scattered throughout the Loop. In some cases stenographers had to cross the street from one building to another and climb three flights of stairs to take dictation. Other problems cropped up: One building was overrun with rats, and another had heating deficiencies. Years later, two of the Bank's original employees wrote of trying to keep warm by resorting to the Dickensian solution of wrapping currency sacks around their feet.10

It was clear that new quarters were needed. Accordingly, the Chicago Fed purchased a 165 x 160-foot lot on LaSalle Street extending from Quincy Street to Jackson Boulevard. The 1918 annual report noted that the property was not only "the most desirable site" in the city for the Bank's purposes, but was "acquired at an exceedingly low cost, the purchase price being $2,936,149."

Having purchased property, the Bank's directors hired the architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst and White to design the building. The firm, which later designed the Continental Bank Building across the street from the Chicago Fed, also built such Chicago landmarks as the Wrigley Building, the Civic Opera and the Merchandise Mart.

Beset by labor and material shortages, the project was delayed for several years. Construction was eventually completed in 1922 at a cost of $7 million. The 1920 annual report depicted the building as "classic in style, fully interpreted to harmonize with modern conditions." The report added that in "line with modern ideas very comprehensive arrangements have been included for the general welfare of the entire working staff. An assembly room, dining rooms, rest rooms...are some of the more important features."

And on to Detroit

As the Bank began planning a new building in Chicago, there was increasing interest in establishing a Branch in Detroit. Fed member banks in the lower peninsula of Michigan had to clear checks and obtain rediscounts through the Chicago Bank, a fairly inefficient process given the geography involved. Frustrated by these time delays, Michigan bankers met in Lansing in 1917 in an effort to build enthusiasm for locating a Branch in Detroit. As the second largest industrial area in the Seventh District, Detroit was a logical candidate, and the Chicago Fed board of directors voted in November 1917 to establish a Branch.

The Branch opened for business on March 18, 1918. The following year, the Bank's annual report stated that the Branch "justified in every way its creation." As expected, the Branch eliminated a delay of one or two days in check clearing, rediscounting and other operations. By 1920, the Branch began to exercise all of the functions of a Reserve Bank except for note issuance and a few minor tasks.

Having proved its worth in its World War I financing efforts, and with the check collection system well in hand, the Fed began to delve gingerly into the relatively unexplored terrain of monetary policy. Throughout the 1920s, the Federal Reserve moved toward increased centralization and coordination in monetary policy. The concept of 12 regional credit policies based on the needs of each district was slowly replaced by a coordinated policy that balanced the needs of each district.

Chicago Sets the Pace for Analysis

An important first step was in the area of research and statistical analysis. In the early 1900s, due in part to the advent of the federal corporate income tax, statistical information on business trends was becoming increasingly available. The Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC, and the Fed Banks began to sort and analyze the data, an effort pioneered by the Chicago Fed. In 1918, the Chicago Reserve Bank established the Statistical and Analytical Department to compile statistical information for the Federal Reserve Board and member banks. The Bank had already begun publishing Business Conditions, a monthly review of the Seventh District economy, in October 1917. Over the next few years, the Chicago Fed began collecting a condensed statement of condition from selected member banks and started a "Business Reporting Service" that gathered data from producers and merchants. As the Reserve Banks refined their research capabilities, the Federal Reserve had a prerequisite for a centralized policy — a flow of information from each section of the U.S. to incorporate into an overall policy.

As the Fed Banks increased their research efforts, they became increasingly aware of a potentially powerful new monetary policy tool — open market operations. When the System was created, rediscounting, or making loans to member banks, was the chief means of affecting credit. It was not until 1921, when the Reserve Banks began to buy and sell government securities to build their earnings, that the potential effect of open market operations was fully realized.

Crafting Monetary Policy for the Nation

In 1923, the Federal Reserve Board established the Federal Open Market Investment Committee comprised of the governors of the Chicago Fed and four other Reserve Banks. Operating under the supervision of the Board, the Committee was instructed to conduct operations "with the primary regard for the accommodation of commerce and business and to the effect of these purchases and sales on the general credit situation."

Even as open market operations became increasingly centralized, the role of the Reserve Banks in setting the discount rate was still unclear. Under the Federal Reserve Act, the Reserve Banks set the regional discount rate subject to the "review and determination" of the Federal Reserve Board.

Dissent with the Board

An early controversy involving the Chicago Reserve Bank highlighted the issue of the discount rate. The incident initially involved Chicago Reserve Bank Governor McDougal and Benjamin Strong, the charismatic head of the New York Reserve Bank, and provided an interesting contrast in styles as well as philosophy. Known as the "Quiet Man of LaSalle Street," McDougal had a reputation for listening a lot and talking very little. Well respected in the financial community, his "integrity and financial sagacity was a byword among Chicago bankers," according to the Chicago Tribune. Strong, one of the leading figures in the Federal Reserve System, was described by contemporaries as an outgoing personality who was a charming conversationalist and a man of unusually strong intellect.11

In 1927, Strong was leading an effort to reduce the discount rate. Strong's outlook was a global one — he favored an easy money policy to aid the European financial position. McDougal, traditionally a conservative in credit policies, opposed the move as did several other Reserve Banks. Strong wrote to McDougal in August 1927 exhorting the Chicago Bank to join a System-wide effort to ease credit. McDougal was not persuaded. In a letter to Strong, he wrote, "It is understood that the governing factor...is the international situation, and it seems to me that the desired result has already been attained through the reduction in your rate." As far as uniformity among the Reserve Banks was concerned, McDougal wrote, "up to the present time we are not convinced as to the necessity of having a uniform rate in all districts."

Strong replied, "My dear Mac: I have read that austere letter of yours...and after finishing it felt as though I were sitting in an unheated church in midwinter, somewhere in Alaska." According to Strong, lowering the discount rate "is neither a New York question nor a Chicago question nor a district question but a national question bearing upon our markets in Europe, consequently an international question."

Still, McDougal and the Bank's board held firm. The discussion erupted into a controversy when the Federal Reserve Board ordered the Bank to reduce its rate on September 6. The Board's action aroused bitter controversy within the System and a fair amount of publicity outside the System. Two of the strongest dissenters against the Board's action were Carter Glass and H. Parker Willis. Strong himself opposed the move and tried to prevent it.12 According to the New York Herald Tribune, the controversy centered on "the long smouldering question of whether in matters of fundamental policy the several regional reserve banks of the system are to be granted self determination. ..."

The Chicago Bank complied with the rate reduction, but also announced that it would seek an opinion from the U.S. Attorney General as to the legality of the Board's action. Later, however, the Bank had second thoughts, and the convenient resignation of one of the Board members supporting the forced discount rate reduction helped to ease the controversy. The issue was not resolved, but the trend toward centralization had received additional impetus.

Challenges on the Horizon

As the Federal Reserve refined its monetary policy efforts, the U.S. experienced a giddy period of industrial growth and high employment through most of the 1920s. In keeping with the confidence of the times, many felt that financial panics had become a thing of the past. As late as 1931, the Encyclopedia of Banking and Finance stated "this country is now thought to be panic proof."13 At the same time, many worried about the extremely high levels of speculative spending. In February 1929, the Federal Reserve Board, as part of its unsuccessful campaign to curtail speculation, decried the "excessive amounts of the country's credit absorbed in speculative security loans."14

Soon after that statement, the stock market began to sour. The plummeting market shook the confidence of the United States. In Chicago, the glum attitude was reflected on October 22 as a band marched up LaSalle Street to celebrate the laying of the cornerstone of the new Board of Trade Building. Many listeners, according to the Chicago Tribune, thought the band should have played a funeral dirge.15 On October 29, the stock market crashed. The Fed responded by easing credit through open market operations and reductions in the discount rate, a policy it continued through the first half of 1931.

Nevertheless, the economic decline continued. By mid-1931, a financial crisis abroad added momentum to the Depression. England abandoned the gold standard in September 1931, a move that shook the international financial community. Fears of dollar devaluation triggered a flow of gold out of the U.S. The Federal Reserve reacted in traditional central bank fashion by tightening credit, the classic method of slowing the flight of gold.

Contributing to the Fed's decision was a requirement of the Federal Reserve Act that gold or eligible paper provide backing for Federal Reserve currency. With eligible paper scarce, the need for gold as collateral increased. In addition, many simply thought that tighter credit was needed. Many commercial banks, understandably skittish after the events of the past two years, kept excess reserves as a cushion, a move that helped convince the Fed that some tightening was needed.16 In Chicago, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle reported that funds were so plentiful that bankers reversed their earlier pleas for liquidity and were in open revolt against the easy money policies of the Fed.17

The Great Depression

The tightening of credit, however, put increased pressure on the economy. The Depression deepened and unemployment rose to 11 million. The Seventh District reflected the nationwide trend. The Bank's annual report noted that "in 1931, as in the preceding year, the Seventh District shared in the world-wide decline in industrial and business activity." The dropping agricultural prices and "unusual number" of bank suspensions fueled the District's sharp decline.

Spurred by the economic problems, Congress passed the Glass – Steagall Act of 1932, which enabled the Fed to use government securities as backing for its notes. During the first nine months of 1932, the Reserve Banks bought an unprecedented $1 billion of securities, but this additional liquidity was quickly absorbed by the parched banking system.18

The economy continued to decline, and industrial activity reached a low point in July 1932. Banks began to feel extreme pressure. In addition to growing loan defaults, the country experienced a wave of currency hoarding. State and local governments began to announce bank holidays. In the Seventh District, a number of local holidays were announced in cities such as Rock Island, Illinois; Muscatine, Iowa; and Huntington, Indiana.19 The piecemeal approach to bank closings accelerated the deposit withdrawals.

As pressures increased, the two dominant banks in Detroit were facing collapse by February 1933. Chicago Fed Governor McDougal, leading commercial bankers, U.S. Treasury officials, representatives of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), and others met to try to resolve the crisis. After studying the banks' books, the RFC declined to provide the large loan necessary to keep the banks open. Private corporations also refused. With no solution in hand, the governor of Michigan declared a statewide bank holiday on Tuesday, February 14. The closing was a severe shock. During the rest of the week, the currency drain on the Chicago Fed was three times greater than for the same period in 1932.20

During the first three days of March panic reached a peak throughout the U.S. as bank customers withdrew huge amounts of deposits. On March 3, the evening before the inauguration of Franklin Roosevelt, the governors of Illinois and New York declared a bank holiday. The executive committee of the Chicago Fed's board of directors met at 10:30 p.m. that night and passed the resolution that the "Federal Reserve Board should urge upon the President of the United States that he immediately declare a bank holiday... in order to give the banks and the governmental authorities sufficient time and an opportunity to provide the necessary measures for the protection of the public interest..." The nation's banking system was effectively shut down.

Although a host of factors caused the banking collapse, many beyond the reach of the Federal Reserve, the fact remained that the Fed was unable to head off the very catastrophe it had been established to prevent. In addition to being hindered by out-of-date legislation, the Fed did not yet have a full understanding of the capabilities and responsibilities of a central bank. Throughout the crisis, the Federal Reserve's progress on the monetary policy learning curve was a step behind the sequence of events.

Roosevelt took quick action once he assumed office. Under the Emergency Banking Act of 1933, banks were reviewed by regulators and licensed to reopen if they were solvent. Confidence was restored and the crisis passed. The cost was high — bank suspensions soared in the early 1930s, reaching 4,000 in 1933. Approximately 30 percent of the suspensions were in the hard-hit Seventh District.21

Birth of the FOMC

With the banking crisis in hand, Congress took on the task of reforming the financial system. Banks were restricted from engaging in securities activities and prohibited from offering interest on demand deposits. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created to protect small depositors against loss. The Federal Reserve was given a powerful new monetary policy tool — the authority to change member banks' reserve requirements.

The Fed also received permanent authority to lend to member banks on the basis of "satisfactory" assets. Previously, the Fed was prevented from lending to institutions that did not have eligible paper to collateralize the loan. The legislation also capped the Federal Reserve's trend toward centralization by creating the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to conduct the System's open market operations. This committee, consisting of the Board and five Reserve Bank presidents, came to be the System's chief monetary policymaking body.

Despite the legislation and the New Deal efforts to stimulate spending, the downswing continued through the 1930s. It was not until preparations for World War II began that the country completely shook off the Depression. Although the Federal Reserve now had its monetary policy tools in hand, and a better understanding of how to use them, fiscal policy dominated the scene for the next ten years. As in 1917, a world war was to absorb the Fed's attention for the next several years.

1Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1919 – 1931, Among Ourselves, Chicago, Various Issues.

2John A. Griswold, 1936, A History of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, St. Louis: John A. Griswold.

3Francis M. Huston, 1926, Financing an Empire: History of Banking in Illinois, Chicago: S. J. Clarke

4Walter E. Spahr,1926, The Clearing and Collection of Checks, New York: The Bankers Publishing Company

5Griswold, op. cit

6Huston, op. cit

7ibid

8F. Cyril James, 1938, The Growth of Chicago Banks, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers

9ibid

10Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago,1919 – 1931, op. cit

11American Banker, 1986, 150th Anniversary Commemorative Edition New York

12Lester V. Chandler, 1958, Benjamin Strong, Central Banker, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution

13Benjamin J. Klebaner, 1974, Commercial Banking in the United States: A History, Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden Press

14Herbert V. Prochnow, (ed.), 1960, The Federal Reserve System, New York: Harper & Brothers

15James, op. cit

16M. Friedman and A. J. Schwartz, 1973, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867 – 1960, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

17James, op. cit

18Prochnow, op. cit

19James, op. cit

20ibid

21Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago,1917 – 1976, Business Conditions, Chicago, Monthly Issues