Redefining Rust Belt: An Exchange of Strategies by the Cities of Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, and Philadelphia

On June 18, 2013, the Federal Reserve Bank branches of Richmond, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Chicago-Detroit hosted a video-conference that brought together community development practitioners and policymakers to discuss the strategies in each city to bring in new residents, retain existing households, and to provide economic opportunities for all residents.

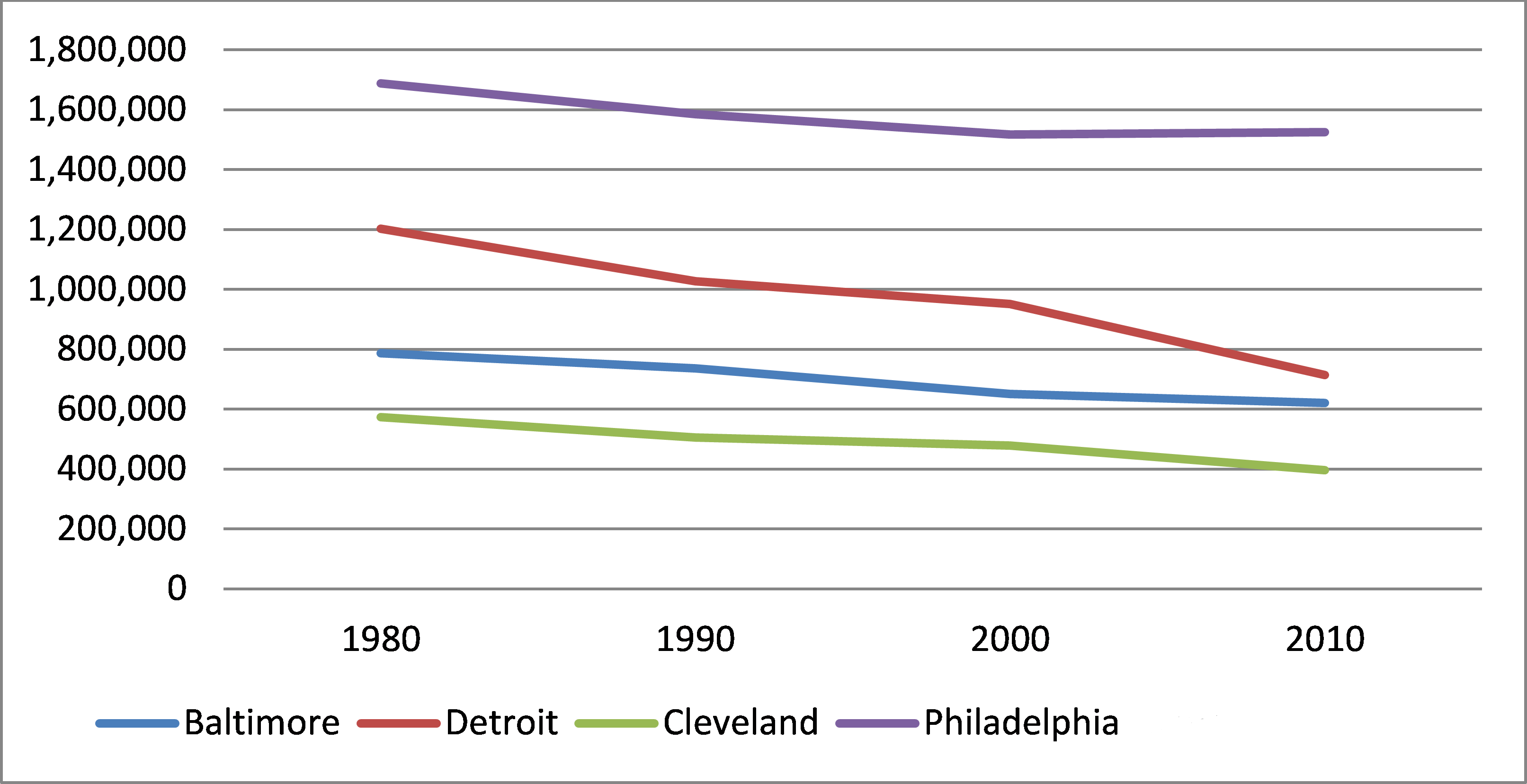

The challenges facing many of America’s “rust belt” cities are well known. Many of the places that drove America’s economic growth through most of the 20th century have experienced deindustrialization and disinvestment for decades. Despite some unique circumstances, the cities participating in the Federal Reserve videoconference exhibit many of the same patterns. These include declines in population (with the exception of Philadelphia which experienced a small increase in population between 2000 and 2010); falling incomes (real incomes have ranged from relatively flat in Baltimore to decreasing by more than 38 percent in Detroit); sharp increases in home vacancies; and declines in the number of employed people relative to the 1980s.

1. Population

2. Median household income (real 1982)

3. Vacancy rate

4. Employment

More recent developments, including the rise and fall of subprime lending, have exacerbated these conditions. The drop in home prices and the overall economic decline have left these cities with a smaller tax base and greater fiscal constraints.

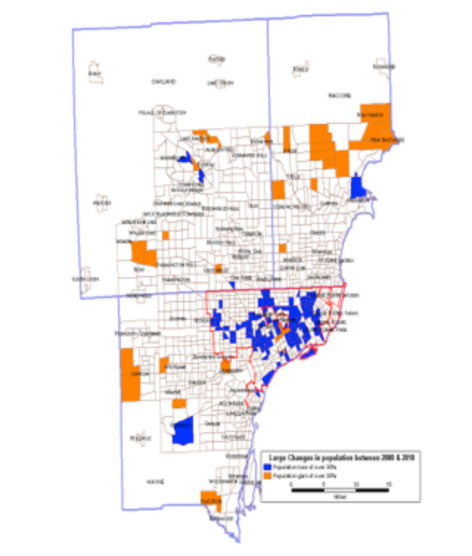

However, the trend in overall population loss masks some dynamic mobility and growth in population that have taken place within the cities. In fact, several of these cities have benefited from a renewed interest in downtown living in recent years. A study by the Brookings Institution shows that between 1990 and 2000, the downtown population of Philadelphia and Cleveland increased by 4.9 percent and 32 percent, respectively. In Detroit, population trends and location dynamics have varied considerably across neighborhoods. The downtown population in Detroit declined by 3 percent between 1990 and 2000, but this rate was much lower than the 32 percent decline in downtown living from 1970 to 1980 and the 17 percent decline from 1980 to 1990. Between 2000 and 2010, neighborhoods in Downtown and Midtown Detroit actually experienced population gains. (Figure 1 shows imputed population changes in neighborhoods in the city of Detroit and Detroit urban area). In contrast, the population in low- and moderate-income census tracts in Detroit decreased by more than 30 percent between 2000 and 2010.

5. Population map

As a means to attract additional residents, each of these cities has been involved in comprehensive efforts to create new economic opportunities at both a city-wide and neighborhood level. Much of the discussion at the videoconference centered on downtown development including environmental amenities and maximizing the economic potential of community assets such anchor institutions and other employment centers. Anchor institutions with world class research and medical centers such as the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, the Cleveland Clinic, and Wayne State University and Henry Ford Health System in Detroit are an important part of this strategy.

For the next year in Detroit, many people within the city’s planning community will continue to focus on the stabilization of the city’s finances. The longer-term vision includes developing commercial corridors in Detroit neighborhoods and building green and blue infrastructure (infrastructure related to managing water, sewer and storm water systems) on the large tracts of vacant land. For more information on the videoconference see National League of Cities blog.