Redefining Rust Belt: The Local Impact of Anchor Institutions in Detroit, Baltimore, Cleveland and Philadelphia

The Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Chicago-Detroit Branch recently held a discussion on the roles of anchor institutions and cultural and art organizations in the revitalization of urban neighborhoods, the second exchange in a series between the four cities on strategies to attract new residents and investments.

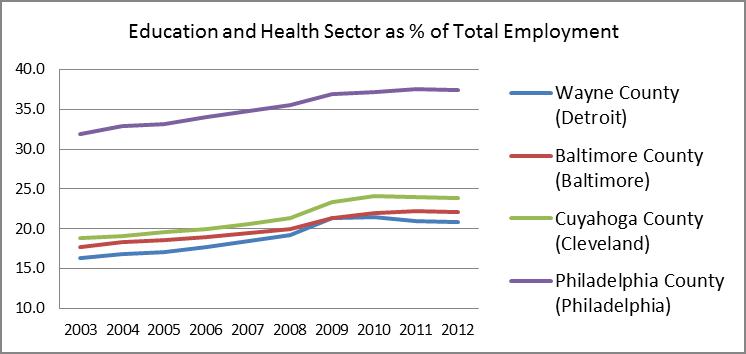

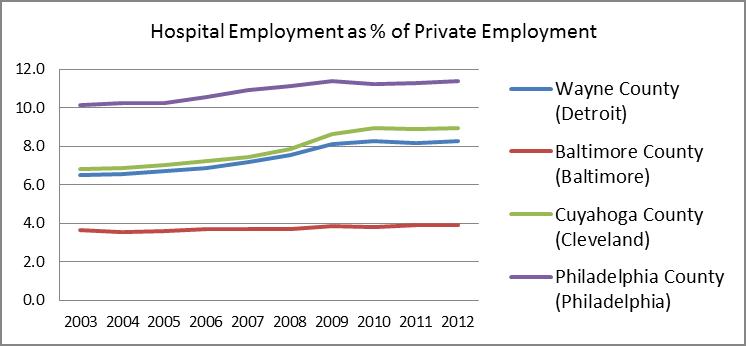

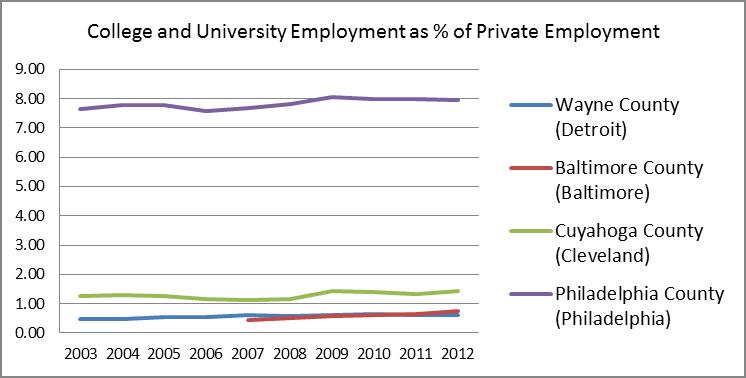

Anchor institutions play an active role in contributing to the economies of cities like Detroit, Baltimore, Cleveland and Philadelphia. Universities, hospitals (“eds and meds” in economic development vernacular), and other large-scale employers, once they are established, often stay rooted in their locations, and thus provide a base for the economic activity in their communities. The impact of these institutions is often felt across their entire cities or metropolitan areas as well, as they employ large numbers of both low-skilled and high-skilled workers, and attract and retain employees, students, patients, and visitors. Data available at the county level show that employment has increased in the education and health sectors even as overall employment has declined in recent years for all four cities. As of 2012, these two sectors together accounted for more than 35 percent of total employment in Philadelphia County, and for 20 percent of employment in Wayne County (where Detroit is located). In Baltimore and Cuyahoga (Cleveland) Counties, the share of employment for those two sectors was close to 25 percent. (See charts). In Detroit alone, some experts estimate that educational and medical institutions hire 3,000 new employees every year, and add $1.7 billion of goods and services to the local economy.1

In the city of Detroit, some of the anchor institutions include Wayne State University, Henry Ford Hospitals, Detroit Medical Center, the College of Creative Studies, and several museums. Arts institutions are increasingly viewed as having the potential to play an anchor role as well. While the employment base of this industry is relatively small, creative outlets add a quality of life dimension, tend to bring people of different walks of life together, and contribute to community diversity and stability.

Rethinking the Concept of Anchor Institutions and Measuring their Impact

Even so, the scope (and scale) of revitalization needs in these cities would be difficult to overstate, and it is unclear just how far place-based institutions’ economic development strategies can take those cities. How successful are in fact these institutions? While many anchors have a nonprofit status, and enlightened self-interest motivates many to care about the vitality of their neighborhoods, to what extent are they optimizing their efforts to affect local residents and contribute to community revitalization?

These were some of the questions raised in the videoconference discussion between experts in each of the four cities, who came together on October 25, 2013 to share strategies and recommendations for attracting investments and growing their cities in ways that provide opportunities for all residents. The initiative was part of a collaborative titled “Redefining Rustbelt,” which seeks to bring together community development practitioners and policymakers to focus on increasing investments, attracting residents, and creating benefits for the people living in these cities, all of which have declining populations.

The conversation uncovered the importance of rethinking the role of anchor institutions in a community, and it offered ideas on some specific instances in which they can effectively contribute to community revitalization. A main takeaway was the importance of effective collaboration and partnerships with the community, a sometimes elusive goal. Ultimately, incentives must be aligned between the anchor institution, neighborhood residents, businesses, and other local advocates in order to ensure large-scale investment that benefits residents and businesses in the adjacent community.

Ted Howard of the Democracy Collaborative framed the discussion with an overview of their work on evaluating the contribution of anchor institutions to surrounding neighborhoods. As he explained, these institutions fulfill their missions when they harmonize their intellectual resources with their prodigious economic power by hiring, investing, and spending to benefit and increase the welfare of surrounding communities. To help institutions assess whether their initiatives actually improve the lives of neighborhood residents, the Democracy Collaborative created the Anchor Dashboard that measures anchors’ quantifiable contributions to economic development, health and safety, the environment, community building and education, among other metrics.

The ensuing discussion gave an opportunity for participants in each city to share their own perspectives on the most compelling aspects of the anchor concept. Noting the distinction between residential neighborhoods and the economic center of a city, several participants offered up the idea that churches, quality schools, grocery stores, and even charismatic leaders often function as anchors of sorts in their neighborhoods. While participants acknowledged the benefit of large-scale hiring by anchors to residents of the community, they also focused on other types of investments that can support the competitiveness of neighborhoods, such as investing in crime reduction strategies, pre-school and afterschool activities, and affordable quality housing programs.

The discussion also highlighted some specific examples of successful investments by anchor institutions that have been useful for community revitalization in each of the cities. In Detroit, for example, these have included residential incentives to increase household density in the Midtown neighborhood. In Baltimore, they have included the development of new housing for residents around the Johns Hopkins campus. In Cleveland, fundraising by three nonprofit arts organizations, along with contributions from the city and state, created the Gordon Square Arts and Entertainment District, generating spin-off businesses and attracting investment for new units of market-rate housing. In Philadelphia, arts and culture organizations have connected to the social needs of neighborhood residents through the Restorative Justice Guild program of Mural Arts, sponsoring mural-creation programs that engage ex-offenders.

Anchors and Community Partnerships, Moving Forward

While participants noted that many anchors have been successful in stepping out of their traditional footprints, setting up outposts in economically-challenged neighborhoods, others suggested that the “anchor strategy” should perhaps be something other than deploying similar programs in various geographies. Rather, it requires community developers to find out who and what are the local agents of change, how to support them, and how to cultivate leadership around them. As some participants noted, successful anchor strategies result from neighborhood actors being motivated to create a community impact, making it difficult for proven projects to be replicated from one neighborhood to the next.

Participants also tended to agree that partnerships are a prerequisite for successful anchor strategies, either between the anchor organization and the public sector, or the anchor organization and other private sector entities. Many participants spoke of the importance of educating elected officials to understand the anchor mission, for the purpose of both convening citizens and anchor institutions, but also for marshaling public resources. In some of the cities, local governments have provided infrastructure improvements, coordinated land planning, acquisition, disposition, and historical preservation processes, and even made direct investments in anchor initiatives. In other cities where the public sector has had fewer resources at its disposal, participants emphasized the role of anchor partnerships with other private sector organizations to provide services related to safety, beautification, and transportation in the surrounding neighborhood. They also noted the opportunity for federal programs to augment the impact of anchor institutions, although many have found it a struggle to make their initiatives conform to all federal guidelines.

Encouraging an anchor institution to collaborate within external entities is often itself a difficult task. Within an anchor institution, the most effective community development leaders tend to be those who have a high level of expertise, have credibility with neighborhood organizations and other external actors, and who have access to the president of the institution. As a participant reminded, indeed the most important explanation for what brings an anchor institution to invest in the surrounding community has to do with its own incentives. Some of the most successful housing and business development projects have come about because of the alignment in incentives between the anchor and the community.

Footnotes

1 Based on research by U3 Ventures consulting and development firm. See http://urbanland.uli.org/planning-design/anchor-institutions-driving-redevelopment-of-detroit-other-cities/