Financial Positions of U.S. Public Corporations: Part 3, Projecting Liquidity and Solvency Risks

This blog post is the third in a series that discusses how the current pandemic affects the financial positions of publicly traded U.S. corporations, the potential implications of these financial developments, and the federal policy response.

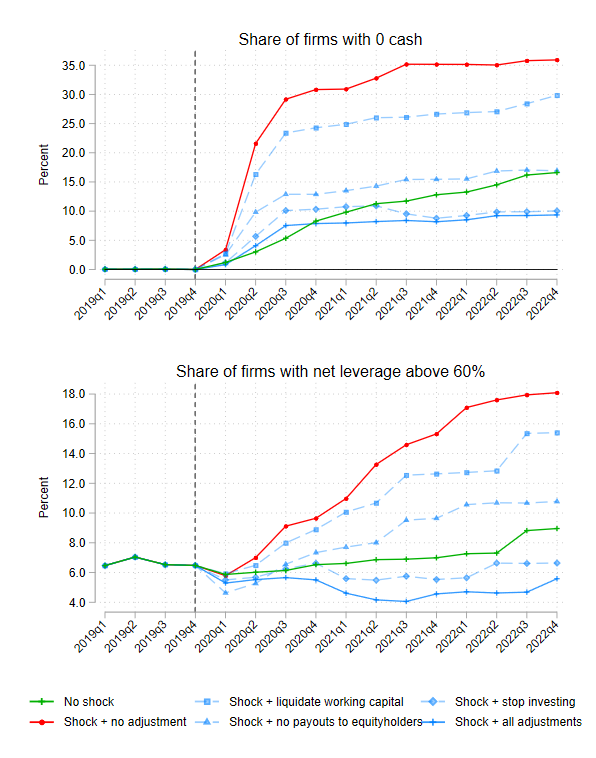

In this post, we attempt to quantify the risk to the solvency and to the liquidity of U.S. public corporations, and how this risk can be reduced or eliminated by firms’ decisions. These calculations should be taken as illustrative only, given the high uncertainty about the evolution of the economy; they do not constitute a forecast, and reflect only the views of the authors and not of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System. First, our calculations suggest that, if firms were to keep dividend payouts, borrowing, and investment at their pre-pandemic levels, our estimate of the shock to earnings caused by the pandemic is large enough that one-fourth of public firms would run out of cash by the third quarter of 2020. Second, if firms solely increase borrowing in response to this liquidity shortage, the additional debt needed to offset the decline in earnings could lead to a doubling of the share of highly levered firms by the middle of 2021 (i.e., firms with a net book leverage above 60%). Third, reducing investment (capital expenditures) and payouts are powerful tools to avoid over-indebtedness. For instance, entirely eliminating investment in 2020 and 2021 would be roughly sufficient to keep the fraction of highly levered firms at the pre-pandemic level.

What do we mean by liquidity risk and by solvency risk?

The pandemic (and the associated social distancing and government-directed shutdowns) has led to sudden large drops in sales at many firms. As a result, many are experiencing negative cash flows. Negative cash flows imply, mechanically, that firms’ cash balances are shrinking. A few firms might be able to get through the pandemic-induced cash flow crunch solely by drawing down their cash balances without any other adjustments. Some firms may also choose to cut back on certain economic activities, such as investing or paying out dividends, so as to conserve cash. And for some firms, these two actions may not be sufficient. Their initial cash balance might be too small or the shock might be too large or too persistent. The firm would then run out of cash. We refer to this eventuality as “liquidity risk.” How widespread is this risk? Or more specifically, how long will it take for firms to run out of cash? And how does this depend on the actions companies might take to reduce cash outflows? This is the first set of questions we tackle in this post.

Once a firm has run out of cash, its only option is to raise additional funding, most likely in the form of debt, to continue operating. This strategy may work for a while, but if debt piles up too high before the recovery starts, the firm might not be able to continue borrowing. At this stage, it may have to stop servicing its obligations. It may then try to renegotiate or delay payments on some of them. At the extreme, the firm may have to enter bankruptcy. Either way, the viability of the firm as a business concern would be called into question. We refer to this as “solvency risk.” Note that it emerges following a continued lack of “liquidity”: It is because the firm has run out of cash and has had to borrow to continue operating that it reaches high levels of indebtedness. Now, we ask a second set of questions: How widespread might the insolvency problem become? How long until firms reach unsustainable debt levels and are forced to default? And again, how does this depend on what actions firms might take to reduce cash outflows?

What are the consequences of illiquidity or insolvency?

Before going into the calculations, we want to discuss the economic consequences of illiquidity or insolvency. The fundamental concern is that either could lead to inefficient exits of businesses, with some loss of intangible or human capital.

In general, illiquidity is not in itself a problem if financial intermediaries or financial markets are well functioning. In that case, a firm without liquidity, but with good future prospects, would be able to raise funds as needed to continue operating. (Of course, financial disruptions could force the firm to exit regardless of its prospects.)

Insolvency carries potentially heavy economic costs. The firm’s counterparties (creditors, but also workers, customers, suppliers, and landlords) would experience losses in case of default. These might be mitigated by transfers (for instance, creditors could repossess some of the firm’s assets), but these transfers themselves could be complicated, costly, and lead to losses of value. In fact, the mere prospect of insolvency might have its own negative effects: For example, suppliers might withdraw trade credit.1 These costs are hard to evaluate and to some extent, they depend on the business model of the firm.2

How can we project liquidity and solvency risk?

To analyze how the current pandemic might impact firm liquidity and solvency, we use the simple cash flow accounting identity:

Change in cash balancest = Operating cash flowt – Investing cash flowt – Financing cash flowt.

Here, the index t refers to an accounting period—one quarter. Operating cash flow consists primarily of earnings, plus the change in working capital,3 minus taxes and interest payments. The investing cash flow consists primarily of capital expenditures on productive assets. The financing cash flow consists primarily of payouts to shareholders (in the form of dividends or share buybacks), plus any net reduction in debt.

In our previous post, we proposed a simple approach to projecting the earnings path of each U.S. public corporation.4 Our strategy is to combine this projection for earnings with the cash flow identity. We can plug the earnings that we estimated into the cash flow identity. Using this, we can then compute the change in cash balances that firms might experience going forward. This can be done firm by firm. And we can iterate this procedure over time to project the entire path of cash balances. This calculation does require some assumptions about firms’ investing and financing cash flows, which in turn depend on what economic decisions—such as reducing working capital, reducing investment, or stopping payouts to shareholders—the firm might take in order to offset the shock itself. We will project cash and debt using various assumptions about these firm decisions.5 Overall, by projecting the change in cash balances, we can compute—given information on firms’ initial, 2019:Q4 cash balances—how long it will take each of them to run out of cash. This provides an answer to our set of questions on liquidity.

1. Projected shares of firms with zero cash and net leverage above 60% of book assets for alternative adjustment scenarios

Once a firm has run out of cash according to our projection, we assume it fills the shortfall by issuing debt,6 and we calculate how indebted the firm might become over time as it does so. This provides an answer to our set of questions on solvency.

It should be kept in mind that there is substantial uncertainty in these projections—chiefly because our assumed path for earnings is highly uncertain.

Liquidity and solvency risk can be avoided, but at the expense of severe cuts to investment... or payouts

What does our simple approach say about the liquidity risk and the solvency risk faced by firms due to the pandemic shock? We find that these risks are significant unless firms sharply adjust their investment or their payout policies during the shock period.7

Consider first the case in which firms make no adjustments in payouts or investment (relative to 2019:Q4) in response to the shock. This is represented by the red lines in the two panels of figure 1. Under this scenario, the top panel shows that approximately 30% of firms would exhaust their cash buffers by 2020:Q3. Compare this to a “baseline” rate (represented by the green line) of 5% if there was no earnings shock.8 Relative to this baseline, an additional 25% of firms face liquidity risk within two quarters if no adjustments to investment and financing are made. These numbers are sales-weighted, so they suggest that about 25% of economic activity of public firms could potentially be affected. Of course, many companies may simply draw down credit lines or borrow more (as many have already done since March) to improve their liquidity position.

What about solvency risk? This takes more time to build up, but the bottom panel of figure 1 shows that in the “no-adjustment” scenario, by 2021:Q2, the fraction of firms with very high leverage (more than 60% of net debt relative to book assets) would have doubled. This assumes, of course, that these firms have managed to convince creditors to keep lending to them throughout 2020, in order to make up for the shortfall between their operating cash flows and their investment and financing costs.

These large numbers suggest that public firms will have to make significant adjustments to their investment and financing policies in response to the pandemic. Figure 1 shows the effects of different potential adjustment strategies.

One adjustment that can help offset the cash crunch and its knock-on effects on liquidity and solvency is to eliminate dividend payouts to shareholders. In this scenario, the fraction of firms that run out of cash by the end of 2020:Q3 declines by about two-thirds, and the fraction of firms that reach very high leverage drops by a similar amount. So, while cutting payouts is helpful, it does not eliminate liquidity and solvency risk entirely.

However, eliminating capital expenditures—investment—would be enough to offset the decline in operating cash flow. Under this scenario, the fractions of firms that run out of cash by 2022:Q4 and that reach very high levels of leverage are virtually undistinguishable from the “baseline” scenario of no shock. Firms could therefore weather the storm by making substantial cuts to capital spending.

This is somewhat reassuring, as it suggests that there are ways for firms to avoid insolvency. But it is also problematic. As highlighted in our first post of the series, public firms tend to be large and contribute a significant share of aggregate investment. If these firms were to indeed eliminate capital spending, it could put a very large dent in aggregate investment for years to come.

This calculation abstracts from government policies that were designed to reduce the risk of this scenario. We will examine these policies in our future posts.

Conclusion

How will the shock to earnings brought on by Covid-19 affect the cash and debt positions of public firms? We used simple computations to highlight two potential risks. First, if firms were to keep dividend payouts, borrowing, and investment at their pre-pandemic levels, the shock to earnings caused by the pandemic could make one-fourth of public firms run out of cash by the third quarter of 2020. Second, if firms solely increase borrowing in response to this liquidity shortage, the additional debt needed to offset the decline in earnings could lead to a doubling of the share of highly levered firms by the middle of 2021 (i.e., firms with a net book leverage above 60%), potentially putting the continuation of their operations at risk. To counteract these risks, cutting shareholder payouts and investment can be powerful tools, but these actions (as well as the employment reductions that underlie our earnings forecast) are themselves likely to have negative macroeconomic consequences.

Notes

1 The prospect of financial distress can also misalign incentives between creditors and owners/managers of the firm, leading, for example, to debt overhang or risk shifting.

2 For instance, airlines have faced numerous solvency crises over the past three decades, but most of them have been able to successfully reorganize using Chapter 11 bankruptcies.

3 Working capital is defined as inventories, plus trade receivables, minus trade payables, plus other short-term assets (excluding cash).

4 To do so, we used observed stock returns during the period from February 20 to March 13, 2020, when it became clear that the pandemic would affect the United States directly, and combined this with the historical relationship between stock returns and future earnings (and made a special adjustment for the transitory nature of the shock). The advantage of this process is that it generates an earning path for all public companies, the weakness is that it may be sensitive to the dates chosen and assumes that historical relationships continue to hold.

5 Another potential adjustment for firms is through layoffs or other employment reductions. The projections for earnings that we construct implicitly take into account potential reductions in employment, as earnings are net of labor costs. Hence, we do not separate out the effects of employment reductions on the liquidity and solvency positions of firms. If firms choose to cut employment more than normal in response to the shock, our results on solvency and liquidity would be mitigated. (Of course, this might also have negative aggregate demand consequences.)

6 Technically, we add the shortfall between operating cash flow and investing cash flow plus financing cash flow to the existing stock of debt.

7 In all scenarios, we assume that firms roll over all existing debt, and that interest payments remain fixed to their average 2019 value. That is, all our scenarios assume well-functioning corporate debt markets. We also assume that corporate taxes are unchanged relative to 2019. That assumption does not affect the results significantly, as firms experiencing large negative cash flow shocks in our exercise typically have small tax bills to begin with. Last but not least, our scenario does not take into account the federal policy response, which we will discuss in future blog posts.

8 The fact that 5% of firms run out of cash by 2020:Q3 in these baseline projections might seem surprising. In order to construct the green line (no shocks), we “freeze” cash flows and other policies at their 2019:Q4 value. Firms whose cash flows during 2019:Q4 fell short of investment and payouts will mechanically exhaust their cash buffers, leading to the slow rise in the share of firms with no cash.