Midwest and the Global Economy Part I

From the slow progress being made on the Doha round of global trade liberalization, it would seem that globalization is slowing down. Yet, this is not the case at all. As the 2002 Economic Report of the President articulated, globalization continues to be enhanced by ever-falling costs and technical advancements in communication and transportation. Such developments are magnifying trade flows of merchandise and commodities and, more recently, services such as software, R&D, call services, and data processing. Springing from these developments in information technology and communication, global capital markets are deepening, which in turn further heightens trade in goods and services.

Regional economies, especially that of the Midwest, are being affected by globalization. Tradable goods such as manufacturing and agriculture products play a significant role in the upheavals of globalization. And so, Midwestern households and business would benefit from timely and appropriate adaptation t

o the globally induced upheavals taking place in industries, companies, and occupations in the region.

Since households continue to learn about globalization from the print media, The Global Chicago Center of the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations and the Ford Foundation are fashioning a project called the Midwest Media Project. The project intends to assist journalists throughout the region to help put local interests in the broader context of global economic developments and events. In this way, Midwesterners can become more attuned to globalization, especially as it relates to the region.

At the first meeting of the project on January 10, researchers and policy leaders are being asked to present globalization topics and information to the attending journalists. In turn, several senior journalists will lead discussions on ways in which global events and trends can be linked to local stories in engaging ways.

I was asked to deliver the overview on the Midwest economy, highlighting the linkages between our region and the world economy. And when I stop to think of the linkages, there are many. For one, given our sharp manufacturing concentration, the Midwest economy is about on par with the nation in terms of exports, and our region’s exports to the world are large and growing. Not surprisingly, it is our “capital goods” that stand out as prominent exports—construction and farm machinery, medical equipment, engines, and electrical equipment. Automotive exports are also prominent, with most of them destined for nearby Canada rather than for far-away locales. As Thomas Klier, automotive expert here at the Chicago Fed has said, “the binational region’s auto industry knows no boundaries.” (Chicago Fed Letter on border conference) Close to 40% of the considerable U.S.–Canada merchandise trade crosses the border in Michigan through the Detroit–Windsor corridor or over the bridge at nearby Huron-Sarnia, much of it being automotive parts and finished vehicles.

Partly owing to this tight automotive production integration, Great Lakes exports to Canada represent 50.4% of the region’s exports versus only 18.2% for the overall U.S. If we were to deduct U.S. exports to Canada from both the Great Lakes region and the U.S., the pattern of export destination by country would be nearly identical for both the region and the overall U.S., with a slight tilt of Midwestern exports to Europe rather than toward Asia.

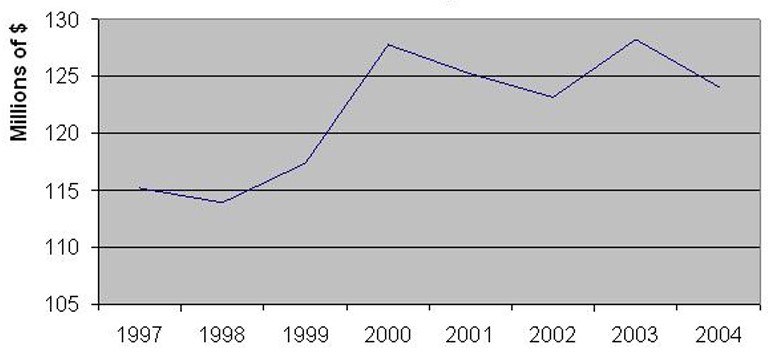

Figure 1. Great Lakes exports

So, too, without our outsized trade with Canada, the Midwest export propensity is significantly smaller in relation to the rest of the U.S. In addition to the region’s proximity to Ontario, landmark agreements to lower tariff barriers to trade between the U.S. and Canada, such as the AutoPact of 1965 and the Free Trade Agreement of 1989, have maintained the close trade linkages between Ontario and the Great Lakes states.

In assessing a region’s (or a nation’s) propensity to trade, should trade with nearby countries be counted equally as trade with faraway ones? In comparing trading intensities across countries or regions, it seems reasonable to at least keep in mind that national boundaries can be somewhat arbitrary. For example, if the boundaries separating states in the Midwest were national boundaries, the trade intensity between the Midwest states would be enormous (link), easily dwarfing current international trade flows into and out of each state.

Table 1. Trade intensity

What do such trends suggest for the region’s economic development policy focus? Growing international trade would seem to support trade missions from the region to foreign countries, many of which are sponsored by state governments. However, the Hewings and Israilevich statistics (above) on the larger volume of intra-regional trade flows might alternatively suggest that public policies to enhance or support local commerce might deserve more emphasis. I see no conflict here; these policy arenas are complementary rather than in competition. We can metaphorically think of the highly integrated binational Great Lakes region as a single factory or service company. Our efforts to encourage free flowing and efficient commerce within the region will serve to strengthen our ability to produce goods and services for trade with the world, which in turn will result in more income for the region’s households and businesses.

One example of local policy of this nature is surely the continued attention to keeping our border-crossing infrastructure and procedures with Canada safe—but also fast and efficient (link). On the U.S. side, the Great Lakes economy will be more likely to prosper if it is the center and nexus of commercial trade flows rather than a peripheral player in the national economy.