Upskilling in Manufacturing

The U.S. work force has been “upskilling” in recent decades, that is, average work force skills have been climbing. Evidence suggests that such upskilling has been taking place broadly across U.S. industries, including manufacturing. However, manufacturers have been especially disappointed by what they see as their inability to hire and retain skilled workers. In response, manufacturers and their associations are quite active in pursuing strategies and programs to fatten their pipelines of skilled workers.

As documented by Dan Sullivan and Dan Aaronson and others, upskilling across the broad U.S. work force is evidenced by rapid growth in educational attainment over the past century, particularly high school and college completion. Rising family incomes over the twentieth century led to unprecedented investments in human capital which were manifested in rising rates of both high school and college attainment. More recently, reasons for continued broad upskilling across U.S. industries and occupations are varied and debated, but the strongest impetus appears to have arisen from rising employer demands for skills. Accelerating technological advancements in recent decades have boosted the demand for workers who can most effectively use these tools in the workplace. In U.S. manufacturing plants, many less skilled production line jobs have been replaced by skilled workers operating computer controlled equipment and working in groups, with individual workers being trained to perform an increasing variety of tasks and operations.

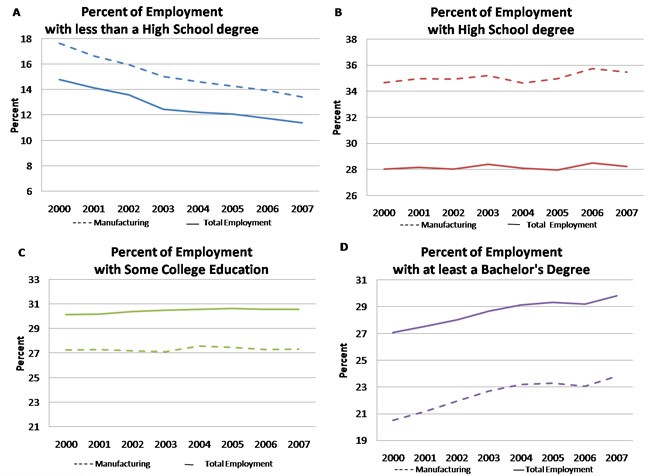

As shown in the figure below using data from the Bureau of the Census1, manufacturing’s general reputation for employing those with lower educational attainment continues to hold into the current decade. For both the U.S. manufacturing and nonmanufacturing sectors, each of the charts reports the share of work force by educational attainment with (1) less than high school, (2) high school or equivalent, (3) some college, and (4) a four-year degree or beyond. As compared to aggregate nonmanufacturing, the manufacturing sector’s work force features more workers with less than a high school degree, as well as those with a high school degree as their highest educational attainment.

Still, for both manufacturing and nonmanufacturing, the shares of workers with the least educational attainment are falling rapidly (see panel A below). Workers with a high school level education also represent a larger share of the manufacturing sector’s work force than in nonmanufacturing sectors of the economy. Here, the share is rising over the decade (at the expense of the below-high school share). For those with “some college” the shares are mostly flat for both sectors, but nonmanufacturing’s share of such workers lies 3-4 percentage points higher. For those with a college degree and higher, the spread widens to about 6-7 points to the advantage of the nonmanufacturing sector. In this instance, the gap between the sectors narrowed ever so slightly over the decade to 2007.

Figure 1. Education attainment

Regional Differences

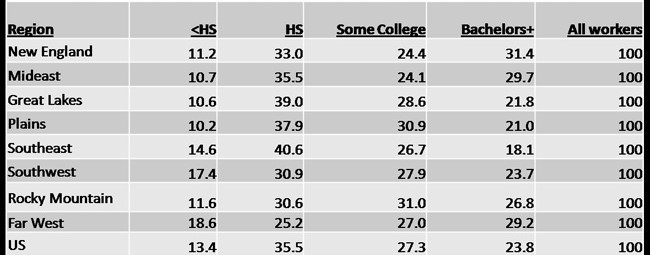

Within the manufacturing sector, educational attainment shares vary by region, in part due to regional variation of types of manufacturing. The New England, the Mideast, and the Far West regions have higher shares of manufacturing workers with at least a bachelors’ degree. These regions also tend to have higher concentrations of high technology manufacturing clusters. On the other end of the spectrum, the Southwest has a higher share of workers with less than a high school education. The Great Lakes region falls in the middle of the distribution. Our manufacturing work force comprises larger shares with educational attainment in the high school and some college categories, with a smaller share of less than high school attainment. Our share of manufacturing workers with a college degree or higher is modestly lower than the national average.

Table 1. Distribution of employment by region and education 2007

The Employee’s Perspective

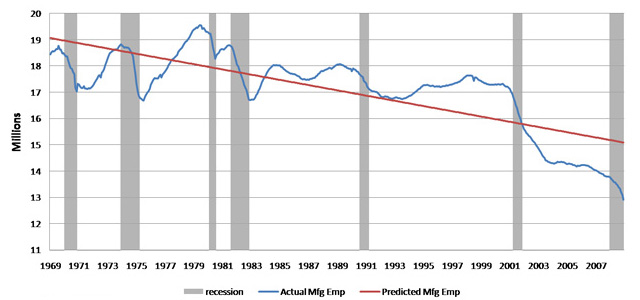

Despite the upskilling taking place in the U.S. manufacturing sector, prospective workers may not perceive robust job opportunities in the sector. Total employment levels have been falling (see chart below). Especially since the 1980s to date, the trend is downward, with an annual average loss of 193,000 payroll jobs per year since 1982. Nor is the pattern of decline very predictable for those who seek to chart a career and training path on the basis of expected employment opportunities. While the sensitivity of employment to the national business cycle is evident, strong structural swings also take place, such as the three million jobs lost in manufacturing nationwide from 1998 to 2003.

Figure 2. Acutal vs. predicted U.S. manufacturing jobs 1969-2008

The Employer’s Perspective

Manufacturers may indeed have an availability problem with their labor market. As the overall labor market in manufacturing continues to shrink in the U.S., the market for workers with particular skills, and usable general skills such as literacy and computational ability, is likely getting thinner. At the same time, skills demanded are rising as global competition heightens and as the U.S. manufacturing sector aims to specialize in more skill intensive goods and services. U.S. manufacturers must also compete for skilled workers with nonmanufacturing sectors in the U.S. which are also upskilling. Surveys of manufacturing employers report widespread concern about the supply of skilled workers and its negative impact on production and customer service.

Wage offers by manufacturing companies to attract workers may be limited by global competition, which may be squeezing profit margins for production operations in the U.S. At the same time, costs of work force training are also under pressure. Traditional or legacy training programs—another avenue for manufacturers to acquire workers—may be similarly squeezed by cost pressures arising from falling numbers of students. That is, when manufacturing job numbers were in the ascendancy, local schools, unions, and employers could more easily gather a sufficient number of students to make the scale of operation affordable.

In responding to their dilemma, U.S. manufacturers are learning to “train and educate” smarter. Their approach has been to encourage programs that identify and define those particular skills that they value in the manufacturing workplace. Such skills are further linked along career pathways by which students or trainees may follow and invest. In this way, training programs and educators will find it easier to construct curricula and career pathways for workers and students. By certifying workers in those skills that employers value and recognize, schools can create incentives for students to invest in skills and training. A further benefit of such skills certification is to reduce search costs in the process of matching jobs and workers, as well as making skills more portable in the process. And since employers can more easily identify desired workers, their available supply of skilled workers will be enhanced.