The Midwest Feels the Sting of an Extended Agricultural Downturn

On November 29, 2016, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago will hold a conference to examine the agricultural downturn in the Midwest and discuss future directions for farming, concluding with a panel discussion on the evolution of agricultural lending. (Check the event page for more details on the conference, including the agenda, and to register.) Experts from academia, industry, and policy institutions will explore the implications of the downturn for both the farm sector and the broader regional economy. The goals of the conference include understanding key trends in farm income, product prices, and input costs; assessing the primary factors behind the sector’s downturn; examining policies that provide support to farm operations and promote risk management; and discussing the role of agricultural lending under these challenging circumstances, as well as in the next phase for agriculture.

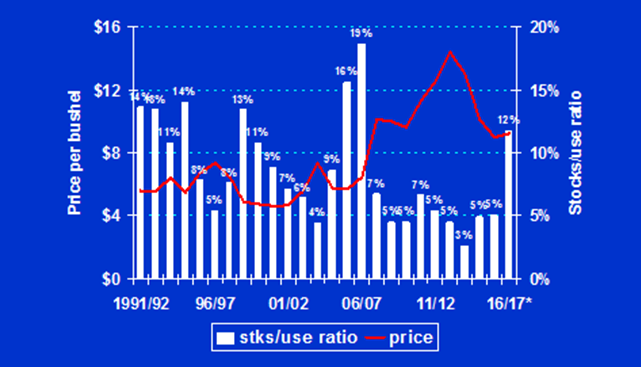

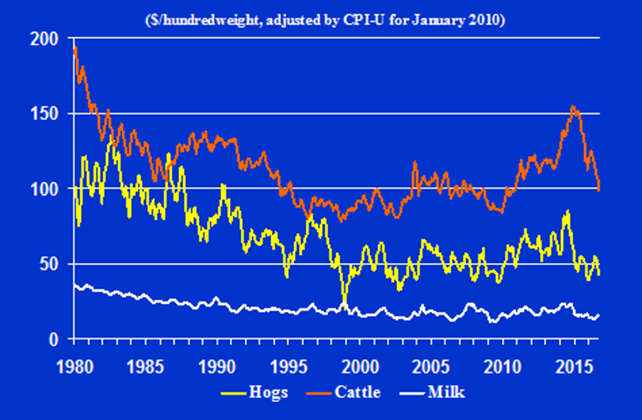

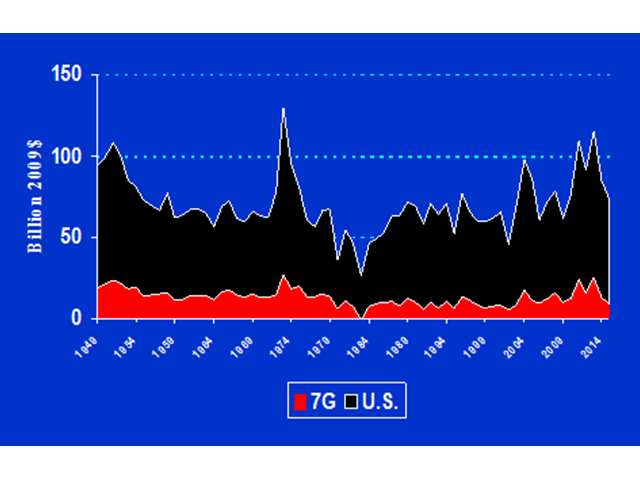

Bountiful harvests since 2012’s drought have replenished crop stockpiles to such an extent that supply has outstripped demand, leading to significant reductions in crop prices for midwestern farmers (see charts 1 and 2). Moreover, livestock product prices have tumbled in recent years (see chart 3). Depressed revenues for crop and livestock operations have translated into lower profits as costs of production have been slower to adjust, particularly for crop farms. This downturn in farm profitability followed on the heels of historically high levels of real net farm income1 (see chart 4). In addition, diminishing income for farm households and operations negatively affected businesses on the Main Streets of towns across the Seventh Federal Reserve District (all of Iowa and most of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin).

Chart 1. Corn prices expected to be down again in 2016/17

Chart 2. Soybean prices not falling again as stocks surge in 2016/17

Chart 3. Real USDA livestock product prices

Chart 4. Real net farm income

This latter point was reinforced through a special question included in the Chicago Fed’s latest Agricultural Land Value and Credit Conditions Survey, to which banks responded during October (results were recently released in AgLetter). Bankers were asked: “Is a weakening agricultural economy leading to weaker Main Street business activity in your area?” In all five states of the District the consensus answer was “Yes,” with varying degrees of certainty—30% said definitely and 43% probably, while only 12% did not agree with this take on current business activity in their areas (15% were not certain of any impacts). Based on these observations, the downturn in farm country appears to have slowed the economy of the rural Midwest on Main Street as well.

As for farm households and farm operations themselves, the U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA) forecasted real net farm income for 2016 to be $64.3 billion, a decrease of 12% from 2015 and the lowest result since 2009 (the most recent reading that was below the median of $66.9 billion from 1950 to 2016).2 In 2009 dollars, net farm income for the U.S. averaged $95.2 billion over the previous five years, dipping down from the prior five-year period ($95.7 billion, a level that was the highest since the period from 1949 to 1953). With farm incomes even higher than during the 1970s farm boom, the just-concluded era of high farm incomes looks likely to have set the bar quite high for the current generation of farmers.

Furthermore, looking at the District, farm incomes were even bleaker. Real net farm income for each state is available through 2015. Using these USDA data, we estimate that the net farm income for the five states of the Seventh Federal Reserve District was $9.1 billion in 2015, a decrease of 31% from 2014 and the lowest outcome since 2003. The District’s value was also below that of the median year from 1950 to 2015 of $12.8 billion. District states accounted for only 12.4% of U.S. net farm income in 2015, after hitting 22% as recently as 2013.

The spillover impacts of farm income declines on Main Street activity in the region can be attributed to the relatively large role played by farmland rentals in the District—39% of net rent received by non-operator landlords nationwide. Such rental transactions provided $5.5 billion for non-operator landlords in 2015, down 27% from a peak of $7.5 billion in 2013 (adjusted for inflation). These payments lift the direct economic impact of agriculture on the District, although some landlords reside elsewhere. Also, $3.1 billion in 2015 was paid out to hired labor by farms in the District (down 8.8% from $3.4 billion in 2014). Additionally, District agricultural operations spent $23.5 billion in real terms on purchased inputs that did not originate on farms in 2015 (declining 10% from 2013’s peak of $26.1 billion), implying that farms reduced their purchases from cooperatives, equipment dealers, and other businesses. These negative effects on income and business activity reinforce a pullback in spending by farm households. Hence, the economic fortunes of agriculture radiate out into communities and the businesses of the District, which are sharing the pain of the current downturn.

At our conference on November 29, the first session will dig deeper into the impacts of the agricultural downturn, especially on farm operations and rural economies. The second session will explore trends in agricultural financing, with a particular focus on bankruptcy research. Following the keynote address by Bill Northey, the Secretary of Agriculture and Land Stewardship for Iowa, there will be a session devoted to the role of farm policy during the downturn and potential directions for future legislation. Finally, a panel discussion will look into the evolution of agricultural financing as distress in the sector builds, as well as innovations in response to the changing farm environment. These sessions should enhance our understanding of the agricultural downturn and provide clues about potential changes that will affect the sector’s future. Visit the event page for more information and to register.

Footnotes

1 Net farm income is a standard way to measure the size of returns from agricultural operations. Basically, net farm income equals the value of agricultural production and net government transactions minus purchased inputs, capital consumption, and payments to stakeholders. See this link for details.