How Will Detroit Spend $826 Million in Federal Aid?

During the pandemic the federal government provided multiple rounds of fiscal support for state and local governments, businesses, and households. One of the larger packages came from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021. Enacted on March 11, 2021, ARPA provides $1.9 trillion in total funding, with $350 billion in support for state and local governments.

In this blog post, I outline the structure of the ARPA funds that are available to state and local governments and describe the strategy that Detroit has adopted to spend its allocation. I also describe some of the challenges that governments will face in using ARPA money effectively.

ARPA’s state and local funding has four goals. First, to provide funds to address the Covid-19 public health crisis and its related economic impact. Second, to provide funding to compensate governments for the four-month decline in revenues that occurred at the start of the pandemic. Third, to provide funds to support an equitable recovery in recognition of the uneven impacts of the pandemic on specific communities. And fourth, to provide direct and flexible funding.

The types of programs eligible for ARPA funds are specified in the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (CSLFRF). Funds can be used to support public health, replace lost revenue, address economic harm to workers and small businesses, provide premium pay for essential workers, and invest in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure. Money cannot be used to offset any loss in revenue related to a tax cut. There are specific funding amounts for different types of governments, including $195.3 billion directly to states, $65.1 billion for county governments, and $19.5 billion for state governments to distribute to local governments with populations below 50,000. For large cities like Detroit, $45.6 billion was allocated based on the Community Development Block Grant programs’ existing classifications and formulas, with some adjustments for measures of poverty, population, housing age, and overcrowding. The funds were to be released in two tranches in May 2021 and May 2022.

Importantly, the funds in the CSLFRF do not include other direct grant programs established in ARPA, such as $126 billion for K-12 education and $40 billion for higher education, as well as a host of other categories, including transit, housing and rental relief, nutrition assistance, childcare, and vaccine distribution. State and local governments had also received funding during the pandemic through the CARES Act and other legislative packages.

ARPA/CSLFRF in action: The plan for Detroit

Detroit will receive $826 million in CSLFRF funding—the fifth highest amount for any city government. A starting point for using these funds was developing a structure for identifying where the funding could best be used in light of the specific challenges facing Detroit, while adhering to the U.S. Treasury’s guidelines for the use of the money. Following this, a process needed to be developed to identify funding needs and opportunities, while considering input from Detroit residents. The city began with a process that was similar to a traditional budgeting process, with the Mayor’s office issuing a draft plan and soliciting public input prior to approval by the City Council.

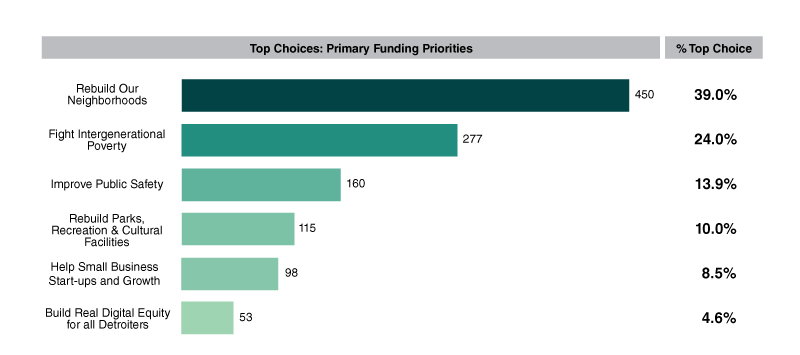

To solicit public input, 65 public meetings were held, as well as an online survey that received more than 700 responses. Figure 1 shows the funding priorities identified through the survey.

1. Top choices: Primary funding priorities

The top two choices (63% of respondents taken together) focused on long-term structural issues facing the city that existed prior to the pandemic, namely neighborhood revitalization and addressing intergenerational poverty.

In response to both the Mayor’s proposal and public input, the City Council created 15 appropriation categories to track how the funds would be spent. Figure 2 shows the appropriation categories, as well as the proposed allocations.

2. City of Detroit Appropriations by Preliminary ARPA EC and Planned Funding Amount

| City of Detroit Appropriation and Description | Primary ARPA Expenditure Category | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| City Services and Infrastructure - to maintain City services; offset revenue shortfalls; and investments in IT and cybersecurity infrastructure | Revenue Replacement (EC 6) | $250,175,290 |

| Blight Remediation - for addressing the elimination of commercial and industrial blight through demolition, remediation, and land reuse | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $95,000,000 |

| Match Funding - for qualifying ARPA projects for which public or private leverage dollars may be made available | Various, to be determined on a project-by-project basis | $30,000,000 |

| Neighborhood Investments 1 - for grants to block clubs and neighborhood associations; neighborhood signs; and community-driven expenditures divided equally into 9 tranches: 7 for projects located in each Council District and 2 for Citywide projects | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $15,500,000 |

| Neighborhood Investments 2 - for Community Health Corps and targeted employment and wraparound services, including community-based gun violence intervention initiatives | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $35,000,000 |

| Neighborhood Investments 3 - for new or expanded improvements for recreation centers | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $30,000,000 |

| Parks, Recreation, and Culture - for green initiatives; parks; walking paths; streetscapes; and arts & cultural investments | Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $41,000,000 |

| Employment and Job Creation - for Skills for Life Employment (Work and Education); Intergenerational mentoring and senior employment; and IT jobs and careers access | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $105,000,000 |

| Intergenerational Poverty 1 - for home repairs to seniors, low income, and disabled community | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $30,000,000 |

| Intergenerational Poverty 2 - to create a city locator service to find affordable housing and provide for housing client management and financial and legal counseling services | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $7,000,000 |

| Intergenerational Poverty 3 - for foreclosure and homelessness prevention outreach and housing initiatives; credit repair and restoration initiatives; down payment assistance; and Veterans' housing programs, including home repairs | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $30,000,000 |

| Neighborhood Beautification - for vacant property cleanouts and alley activation | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $23,000,000 |

| Public Safety - for traffic enforcement; gun violence initiatives; DPD training facility improvements; and EMS bays at firehouses | Public Health (EC 1) and Services to Disproportionately Impacted Communities (EC 3) | $50,000,000 |

| Digital Divide - for devices; internet access; and technology support initiatives | Water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure (EC 5) | $45,000,000 |

| Small Business - for landlord support; small business recovery programs, including interest reduction and credit support programs; small business capacity building; development stimulus programs; and corridor investments | Negative Economic Impacts (EC 2) | $40,000,000 |

| Total Appropriations | $826,675,290 |

Source: City of Detroit Recovery Plan.

CSLFRF was designed to allow governments to tailor spending to reflect the impacts that the pandemic has had on their local economy. Governments needed to balance offsetting direct losses from Covid-19 impacts with the opportunity to use CSLFRF money for structural investments and addressing longer-term inequities. For Detroit, the largest spending category, 30%, is for revenue replacement and investments in information technology and cyber security. There are two reasons why revenue replacement is so important: 1) The relative impact of the pandemic on the city and the revenue structure meant that Detroit lost a significant amount of revenue; and 2) the terms of the city’s bankruptcy plan require it to maintain certain funding levels.

Detroit’s revenue structure was significantly damaged by the pandemic, and potentially these effects will be long lasting. In particular, Detroit’s largest own-source revenue is provided by a local income tax, which is heavily funded by non-resident workers, who are subject to the tax for days they are physically working in the city. These non-resident income payments dropped precipitously during the pandemic as workers transitioned to fully remote status. In February 2022, the city reported that individual income tax payments had fallen from a high of $295 million in FY19 to $261 million in FY20, and projected a further drop to $232 million in FY21. A large percentage of this drop was fueled by the loss in non-resident income tax payments. Importantly, these revenue declines are expected to persist as many workers continue to work remotely several days per week—keeping total individual income taxes below FY19 levels through FY23 ($274.9 million).

The bottom line is that not only did Detroit face a revenue challenge during the pandemic but it will continue to experience the fallout for years to come.

In terms of total recurring general fund revenues, Detroit saw a decline of $121.7 million (11.6%) from FY19 to FY20. However, recurring revenues are estimated to be above FY19 levels by FY22 ($1.086 billion vs $1.042 billion) and are forecasted to grow to $1.213 billion by FY26.

An additional reason for the large share of funding going to revenue replacement had to do with the adjustment plan for Detroit that emerged as part of the bankruptcy settlement finalized in 2014. The plan created a restructuring and re-investment initiative (RRI), which requires the city to maintain certain service levels, as well as city worker employment levels.

How does Detroit’s plan reflect input from city residents?

Figure 3 shows the funding allocations for the six top priorities identified by Detroit residents. The level of funding for each category does appear to reflect the identified preferences of residents; however, as a share of the full $826 million provided to Detroit, these six categories only receive roughly 42%. This in large measure reflects the city’s need to use funds for revenue replacement rather than new program initiatives, with the remaining balance made up by smaller program initiatives.

3. Funding allocations for Detroit residents’ top priorities

| Priorities identified by residents | Amount ($ millions) designated for the purpose by Detroit | Share of total ARPA funds for Detroit |

|---|---|---|

| Number 1 (39% of respondents) Rebuild neighborhoods—3 direct neighborhood investment designations, 1 neighborhood beautification | 103 | 12.5 |

| Number 2 (24% of respondents) Fight intergenerational poverty—3 direct categories | 67 | 8.1 |

| Number 3 (13% of respondents) Improve public safety—1 direct category | 50 | 6.0 |

| Number 4 (10% of respondents) Rebuild parks, recreational and cultural centers—1 direct category | 41 | 4.9 |

| Number 5 (8.5% of respondents) Help small business—1 direct category | 40 | 4.8 |

| Number 6 (4.6% of respondents) Digital access and equity—1 direct category | 45 | 5.4 |

| Total for 6 priorities | 346 | 41.9 |

Progress to date

On January 25, 2022, the City Council was provided with an update on projects using CSLFRF funding. A total of 51 projects had been submitted. Projects are required to go through a multistage approval process that includes internal and external reviews and the development of outcome measures. Thirty of the 51 projects are in the implementation phase, representing roughly $458 million in program funding. Of this, $165 million has been dedicated to help fund the post-bankruptcy adjustment plan.

Roughly $155 million is for programs still under development. The city also created processes that allow for matching funding by other governments, corporations, or philanthropic organizations, with all match funding requiring City Council approval. Targets for match funding include mental health services and home repair services.

ARPA also includes allocations to state governments, county governments, and school systems. Michigan state government will receive $6.5 billion in funding, Wayne County gets $339.7 million, while Detroit schools are slated to receive $700 million (although the school allocation is separate from the CSLFRF allocation). This level of funding, which potentially overlaps with the Detroit city government plans, points to a further complexity of coordinating spending across governments when the funds must be spent within two years. For example, the Detroit school system released its proposal for using ARPA funds on February 15, 2022. The expenditures are largely for capital improvements to school buildings. Like the city process, the schools plan will receive input from public hearings. This somewhat slow start to the process puts pressure on the system to approve a plan to ensure funds are allocated during the necessary spending window. Plans for spending Michigan’s state allocations have produced several proposals but no consensus to date.

Conclusion

Many analysts have suggested that CSLFRF represents a once in a lifetime infusion of federal resources for state and local governments. The program is somewhat unique in terms of both its relative flexibility and its goal of addressing inequality and differential impacts of the pandemic on specific communities. Following and understanding the choice of programs and their impacts on communities will continue to be an important research question for many years.

There are several challenges that bear watching. First, there is the need to spend the money within two years; and second there is the likelihood that many programs will need additional funding beyond the two-year ARPA window. In addition, the need to develop immediate plans for using the money limits stakeholders’ ability to stand up new programs from scratch and likely creates an incentive for them to spend the money through existing channels.