A growing body of work by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and partners points to challenges that "legacy cities"1 face in extending economic opportunity to all residents.2, 3 A recent study involving both in-person interviews and data analysis highlighted how community leaders from legacy cities uniformly spoke of a desire to attract new businesses and workers while acknowledging the challenge of connecting these opportunities to current residents. This enduring challenge exists within many (if not most) legacy cities whose economies shifted away from manufacturing decades ago. The study underscores a new realization among legacy city leaders that a city’s full economic potential will not be reached if major portions of their populations remain outside the (living-wage) labor force and economic mainstream.

While policymakers and non-government leaders acknowledge and understand the challenge of extending inclusive growth to all residents, few concrete strategies have emerged, and it remains unclear how and to what extent leaders are working toward economic inclusion in legacy cities. In order to better understand what legacy cities were doing to advance positive labor market outcomes for their residents, the authors, in partnership with The Funders Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities4 convened a series of focus groups around the Seventh Fed District5 with leaders in some of the region’s smaller cities.

For the purposes of this study, we did not offer a single definition of economic inclusion; rather, we formed a working definition with input from participants (the first question asked during focus group sessions was, “How do you define economic inclusion?”), and drawing from various institutional definitions, identified as part of a brief literature review. A cross section of these sources reveals a few key points:

- Economic growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition to foster economic inclusion.

- Economic inclusion is not about redistributing the benefits of economic growth; it is, instead, an ingredient of a more durable strategy for growth.

- Economic inclusion requires economic development strategies that break down barriers and deliver opportunities to underserved populations, placing responsibility on places and institutions rather than individuals.

We framed our focus to discussion participants as one of exploring ‘economic inclusion,’ to align it with other comparable discussions and studies. We sought to better understand the ambitions of city leaders of older, primarily smaller, Midwest cities, and what they saw as challenges and opportunities. Economic inclusion has become an aspirational imperative for places, especially those that have diligently pursued strategies of economic growth only to find that economic well-being did not improve for all residents. Growth alone does not address underlying challenges of equity and opportunity.

For this study, the emphasis was on cities, and primarily on smaller cities (of less than 250,000 population), including many that are not within a major metropolitan area. Because these conversations took place in the Midwest, these cities often have a manufacturing legacy and have unique histories as destinations for blacks during the Great Migration (roughly 1910 to 1970), which has an impact on their labor experiences and profiles. Of course, cities are also intrinsically linked to their regions in terms of labor market characteristics, and therefore discussions about cities must take into account their regions.

This article presents some of the initial findings from our focus groups. While preliminary in nature, we highlight emerging themes across groups. We also attempt to make the case for further inquiry of the type presented in the literature, including reaching a definition of economic inclusion. We provide some descriptive data for context and a methodological overview of our study.

Methodology

Leveraging the extensive community networks developed by the Community Development and Policy Studies department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the authors organized focus groups around the Reserve Bank’s Midwest region in order to explore how the understanding of and movement toward economic inclusion was evolving in those places and, in turn, what could be learned that could be shared or scaled. Our partners in the effort, The Funders Network, were also present to learn about strategies or initiatives that could be supported at the local level.

Local project partners that hosted the focus groups included economic development intermediaries and local community foundations. Focus group participants included a broad range of community stakeholders, such as:

- City economic/community development

- Other city departments

- Elected officials

- Private sector business

- County economic development

- Community development sector (local community development organizations and intermediaries)

- Higher education

- Workforce development

- Chambers of commerce

- Primary/secondary education

- Social services

- Philanthropy

Within these parameters, the exact composition of the group was largely left to the discretion of the local organizer. A standard list of questions was asked, although not always in the same order, allowing the conversation to flow organically while still ensuring that all topics were covered.

Focus groups were held in the following locations between September 2017 and January 2018.

- Rockford, Illinois

- Fort Wayne, Indiana

- Peoria, Illinois

- Bloomington-Normal, Illinois

- South Bend, Indiana (3)

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin (4)

- Aurora, Illinois

- Lake County, Indiana

- Decatur, Illinois

- Champaign, Illinois

- Flint, Michigan

- Detroit, Michigan

- Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Each focus group discussion was recorded and transcribed. Participants were assured of their anonymity. Each transcript was coded by three researchers using a qualitative data analysis computer software package, looking for key themes that cut across places or along labor market conditions.

Literature overview

What is economic inclusion?

Definitions of ‘inclusive economies’ in community development and policy literature vary. The presence of economic growth and of broad-based benefits of that growth is a common assumption in these definitions. However, inclusion means not only ‘benefiting from’ but also ‘contributing to’ a growing economy. Definitions also focus on the removal of barriers, placing that responsibility on a place or a system, rather than the person. For example, the Rockefeller Foundation defines inclusive economies as “expanded opportunity for more broadly shared prosperity, especially for those facing the greatest barriers to advancing their well-being.”6 To help measure what constitutes an inclusive economy, Rockefeller highlights five broad characteristics: equity, participation, growth, sustainability, and stability. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines inclusive growth as "economic growth that is distributed fairly across society and creates opportunities for all."7 Brookings’ Metro Monitor describes inclusive growth as “a process that encourages long-run growth by improving the productivity of individuals and firms in order to raise local living standards for all.”8

The Urban Institute frames inclusion as “the opportunity for all residents – particularly historically excluded populations – to benefit from and contribute to economic prosperity.”9 One 2009 World Bank study defined inclusive growth through rapid and sustained poverty reduction “that allows people to contribute to and benefit from economic growth.”10 They added that for grown to be sustainable, it should be broad-based across sectors and inclusive of the large part of the country’s labor force.

Why does economic inclusion matter to places?

A brief review of the literature conveys the importance of economic inclusion in cities. First, cities are centers of economic growth by virtue of low-cost mass economizing transportation and encouraging specialization and trade, while facilitating learning and new ideas.11 However, as Ed Glaeser et al. find, as cities grow, income inequality also tends to increase. Their explanation for why this happens is that, in part, economic growth relies on firms that are capital-intensive and use high-skilled workers (such as those with college or post-graduate degrees). Such firms also generate productivity benefits from locating near one another. Over time, growing cities attract more high-skill workers and capital-intensive firms as they grow, and because low-skill workers face barriers in acquiring skill, wage inequality rises. Glaeser et al. find that city-level skill inequality, rooted in historical schooling patterns and immigration, can explain about one-third of the variation in city-level income inequality.12

Further, cities demonstrating inclusive growth also have faster economic growth, with spillover effects of lower crime rates and lower levels of unhappiness (as reported by residents).13 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) with higher per capita personal income growth rates have lower poverty and inequality, reflecting a cycle of poverty reduction and economic growth.14 Longer growth spells are correlated with lower levels of income inequality and measures of social segregation, suggesting a virtuous cycle between economic inclusion and sustainable growth.15

However, it is also worth understanding the extent to which efforts to counteract economic ‘exclusion’ and growing inequality can be impacted by economic downturns. One study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that after the labor market returns to a normal state from a period of higher growth, the benefits from that period to disadvantaged groups, especially less educated men, essentially disappear after three years.16

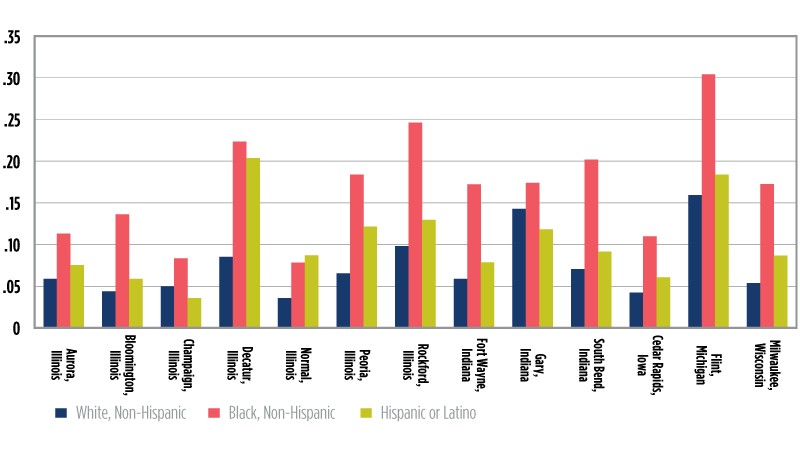

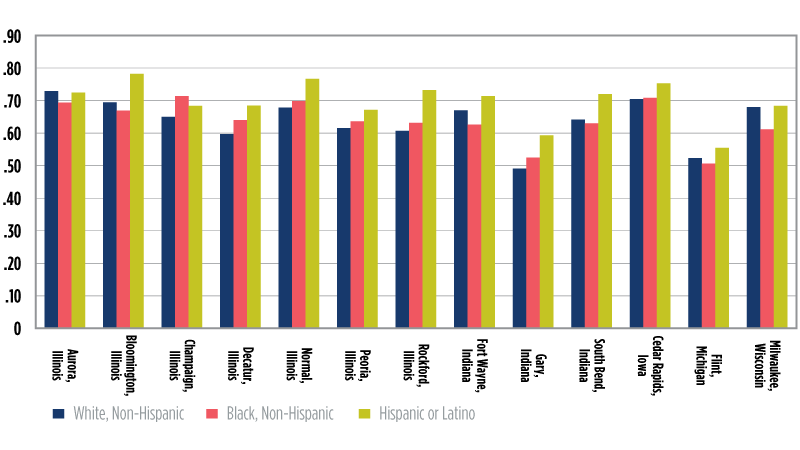

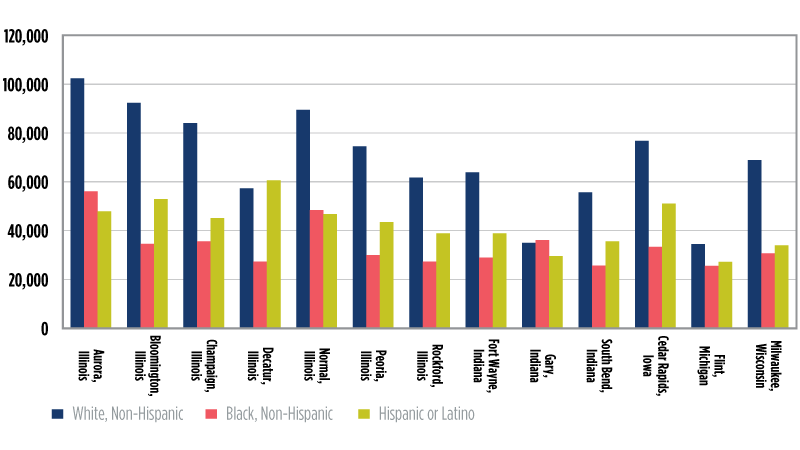

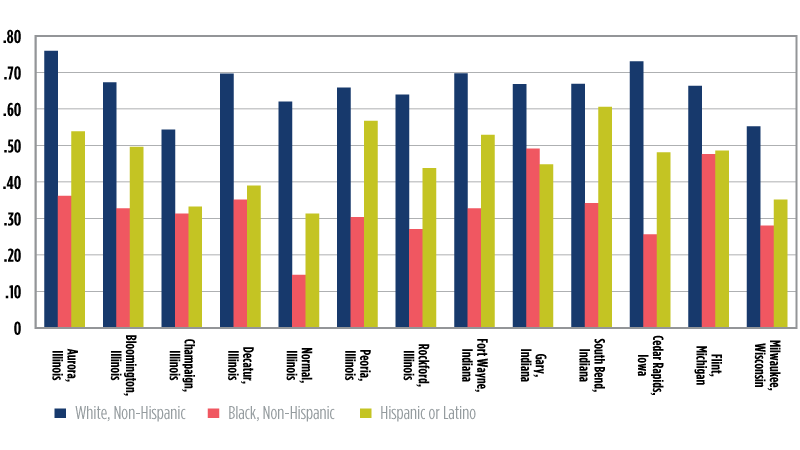

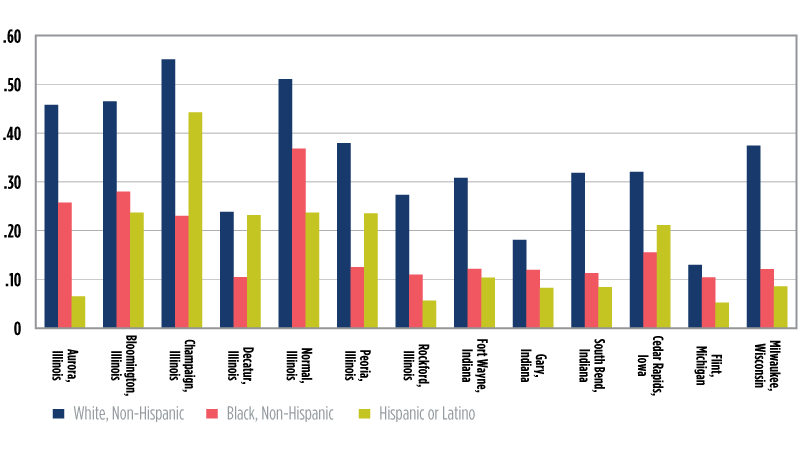

Data overview

From a data perspective, economic exclusion manifests itself in disparities – most commonly along racial lines. Although race was a commonly cited barrier, it was not the only one. Others, including age, faith, immigration status, and disability, were mentioned as well. Indicators that can provide measures of exclusion include those related to educational attainment, income, homeownership, employment, and others. The places we visited are not immune to these disparities, nor are their experiences unique. Figures 1 through 6 (at the end of the article) illustrate racial and ethnic disparities across several dimensions. These data exhibit familiar patterns for individuals involved in studying/addressing urban challenges and related policy. Economic conditions for whites in these cities are uniformly better than those for blacks and Hispanics: unemployment rates are lower, poverty rates are lower, and incomes are higher, as are homeownership rates and educational attainment levels. Notably, labor force participation rates across all of the cities visited are comparable or higher for minority populations, underscoring that labor force engagement alone does not always lead to economic benefit.

Initial findings from focus groups

Labor market conditions matter

Quotes from participants:

“I think as our labor shortage has grown, that the temperature on the conversation [about economic inclusion] has gone from simmer to hard boil.”

“We’re having big discussions about the idea of inclusion. We’re having big discussions about the idea of how do you include immigrants and refugees into the discussion. We’re having big discussions about how do you make sure that people with disabilities are included in the discussion. But so much of it is driven by the fact that we have major labor shortage problems.”

“There was not nearly as many people interested in supporting workforce development during the recession as there is now that there’s not enough employees for its employers.”

Labor market conditions appear to influence efforts at inclusion, according to focus group participants. A tight labor market, where employer demand exceeds a perceived level of labor supply, provides an opportunity to bring marginalized populations into the labor force, but in places with little or no economic growth the challenge is greater. The places visited displayed a spectrum of labor market and economic conditions, from 4 percent unemployment to 25 percent unemployment, 5 percent family poverty rate to more than 35 percent, and barely 50 percent labor force participation to more than 70 percent. Conversations in these places were markedly different. Participants in tight labor market cities could name initiatives and programs to engage marginalized populations in the workforce. Expanding the workforce was an economic imperative for these places in order to meet demands from employers. In places where there was little or no growth, while the awareness of the importance of economic inclusion may have existed, opportunities to put it into practice were limited. Conversations in places that exhibited low growth conditions focused on persistent barriers where a chronic lack of equity undermined efforts to build trust.

Human capital conditions are complex

Quotes from participants:

“And so how do we, as people who work in economic development or other related industries, think about removing socioeconomic, social cultural, physical barriers to access to jobs and education, and all those basic things that help you be an active participant in the economy?”

“Childcare does keep a lot of people home from jobs, or they’re not able to go to work and then they end up losing their jobs, things like that.”

“If other communities in the MSA are pulling our bachelors-plus educated, those jobs are going there, those businesses are going there. And those that don't have a bachelor’s degree or even high school diploma don't have the chance to get out. And so that leaves us to locally address that need.”

“We are in a struggle. We don’t have a city, meaning community that is sustainable. It’s hard for me to separate the big systemic failures, which are making life really difficult here, from the depth of that trust chasm that we’re trying to overcome.”

Residents carry with them legacy and/or emerging barriers to employment. Ranging from the impacts of historical federal policies that legitimized racial screens, to language differences, to felony records, to a lack of educational attainment, focus group participants named a range of barriers that were carried by people regardless of location. The first and most important conclusion conveyed by participants was that barriers to employment were complex and often multifaceted. Removing one barrier often revealed another, and some barriers, for example cost of childcare, might prevent individuals from pursuing strategies to eliminate other barriers, like lack of education.

Within the complex interplay of barriers, it was clearly articulated that places can impact inclusion by addressing place-controlled barriers to employment such as transportation (sometimes), childcare, targeted training (often in partnership with community colleges), and K-12 education (although there were sometimes conflicting and overlapping units of government). However, almost as important is how residents receive and share information regarding opportunities. Focus group participants frequently referenced the need to receive information from trusted sources and most often those were powerful, yet sometimes fragmented, grass-roots organizations that were well-known to residents in their communities.

A related conclusion is that leaders in places have the option to anticipate emerging barriers, such as the need for affordable, workforce housing when growth opportunities are on the horizon. While challenging and uncomfortable to plan for the departure of a major employer, or an overall downturn in the economy, being proactive in anticipating labor market changes – positive or negative – has the potential to improve labor market outcomes, and allows equity-based decision-making to become standard practice.

Setting the table

Quotes from participants:

“Sometimes it is the source and the deliverer of the information. Because I would say that there are definitely persons in our community who will not trust certain things coming from certain places or people. It would have to be delivered by a trusted source.”

“And there are segments of the community that don’t fully participate for a variety of reasons. Some of it is access. Some of it’s that they don’t trust where information is coming from. Some of it is because there’s a disconnect between the information that they’ve been given and where opportunities really exist currently and on the horizon.”

Convening, connecting, and empowering a diverse array of community representatives is extremely important to successful economic inclusion strategies. These include not only those responsible for job attraction and retention (often the economic development organizations), but also those responsible for developing and training workers for opportunities (often educational – primary and secondary – institutions, as well as community colleges). However, just as important are the often grass-roots organizations that are known and trusted sources of information within neighborhoods. And, finally, there was a range of individuals and organizations that brought resources – financial as well political – that impacted where and how opportunities manifested themselves. These may be elected leaders, but also potentially bankers or philanthropists. Those places that ‘set the table’ with this diversity of perspectives were often well-equipped to hear and address conversations around economic inclusion. Participants in some places expressed concern about who was missing from the conversation – sometimes specific populations, sometimes specific individuals, sometimes private entities. Nevertheless, across the places visited there was agreement that in order for economic inclusion to be successful, it needed to connect within and across the systems of power and community, as well as growth and opportunity.

Making the case

Quotes from participants:

“I don’t get to define your self-interest. You don’t get to define mine. I have to understand your self-interest. You have to understand mine. And we have to figure out how to align those.”

“And I think how you position the argument around how we can get people on board with (inclusion) is not about equity. It’s not about sharing power and sharing the pie. It’s about figuring out how you deliver the message in someone’s self-interest.”

“So I think overall there’s a feeling of we want to uplift each other, but not sometimes when you feel that there’s personal risk involved, then there’s still the backlash.”

Conversations about economic inclusion were well-established among economic development professionals and social service providers. However, participant comments revealed that for many the ‘business case’ for economic inclusion still needs to be made. For others, economic inclusion carried with it an element of risk to or potential loss of something they felt they had earned. Participants especially mentioned challenges in building consensus on longer-term goals (such as improving local schools to build a workforce pipeline), when there were near-term needs that appeared more pressing. With scarce municipal resources, and absent federal support, cities are forced to ‘triage’ competing challenges. Making the case that “inclusion is not charity” will help align discussions and initiatives within broader economic development strategies.

Conclusion

Economic inclusion has become a term of art signifying efforts to address a range of challenges faced by places and their marginalized (or disenfranchised) residents. Our contribution to this conversation is a focus on how, and whether, economic and community development practitioners are addressing economic inclusion in their cities. Local labor market conditions have a significant impact on discussions and actions around economic inclusion. But even those places facing optimal conditions of economic growth must be intentional in how they connect all residents to available opportunities. Places facing low or no growth conditions can nevertheless prepare residents for opportunities by working to remove legacy barriers, one of various challenging tasks in capacity constrained environments. However, regardless of the conditions under which economic inclusion is advanced, understanding that the case for why economic inclusion matters to the health of regional and local economies, rather than just to a population within a place, is not yet widely understood or accepted.

Figure 1. Unemployment rate: ACS 5 year 2016

Figure 2. Labor force participation: ACS 5 year 2016

Figure 3. Poverty rate: ACS 5 year 2016

Figure 4. Median family income: ACS 5 year 2016

Figure 5. Homeownership rate: ACS 5 year 2016

Figure 6. Educational attainment: ACS 5 year 2016

NOTES

1We use the term “Legacy cities” to refer to smaller, older cities with economies historically (but for the most part no longer) concentrated in the manufacturing sector.

2 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Resources for Industrial Cities Initiative, available at https://www.chicagofed.org/region/community-development/community-economic-development/ici/ici-profiles. The Community Development and Policy Studies Division created the Industrial Cities Initiative to gain a better understanding of the economic, demographic, and social trends shaping industrial cities in the Midwest. The ICI was motivated by questions about why some Midwest towns and cities outperform other cities with comparable histories and manufacturing legacies. And, can "successful" economic development strategies implemented in "higher-performing cities" be replicated in ‘underperforming cities?’

3Looking for Progress in America’s Smaller Legacy Cites: A Report for Place-based Funders, available at https://www.chicagofed.org/region/community-development/community-economic-development/looking-for-progress-report. This paper describes a study tour undertaken by representatives from four Federal Reserve Banks and more than two dozen place-based funders, under the auspices of the Funders’ Network-Federal Reserve Philanthropy Initiative. This inquiry into four small legacy cities – Chattanooga, TN; Cedar Rapids, IA; Rochester, NY; and Grand Rapids, MI – that appeared to have experienced some measure of revitalization in the post Great Recession environment evolved into an understanding that revitalization in these places and broad community prosperity lies in: 1) recognizing that growth alone does not naturally lead to opportunity; and 2) advancing deliberate policies, investments, and programs that connect growth to opportunity.

4The Funders Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities, available at https://www.fundersnetwork.org.

5The Seventh District comprises the state of Iowa, roughly the northern two-thirds of Indiana and Illinois, the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, and southern two-thirds of Wisconsin.

6Benner, Chris, and Manuel Pastor, 2016, “Inclusive Economy Indicators: Framework & Indicator Recommendations,” December, available at https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20161212162730/Inclusive-Economies-Indicators-Full-Report-DEC6.pdf.

7See http://www.oecd.org/inclusive-growth/#introduction.

8See https://www.brookings.edu/research/opportunity-for-growth-how-reducing-barriers-to-economic-inclusion-can-benefit-workers-firms-and-local-economies.

9Poethig, Erika C. et al., 2018, “Inclusive Recovery in US Cities,” April 25, available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/inclusive-recovery-us-cities.

10See http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDEBTDEPT/Resources/468980-1218567884549/WhatIsInclusiveGrowth20081230.pdf.

11Krugman, Paul, 1991, “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 99, No. 3, June, The University of Chicago Press, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937739.

12Glaeser, Edward L. , Matt Resseger, and Kristina Tobio, 2009, “Inequality in Cities,” October 1, Journal of Regional Science, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00627.x.

13Ibid.

14Dev Bhatta, Saurav, 2003, “Are Inequality and Poverty Harmful for Economic Growth: Evidence from the Metropolitan Areas of the United States,” Journal of Urban Affairs, April 16, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0735-2166.00093.

15Benner, Chris, and Manuel Pastor, 2014, “Brother, can you spare some time? Sustaining prosperity and social inclusion in America’s metropolitan regions,” Sage Journals, September 5, available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042098014549127.

16Fallick, Bruce, and Pawel Krolikowski, 2018, “Hysteresis in Employment among Disadvantaged Workers,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, working paper No. 18-01, February, available at https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/working-papers/2018-working-papers/wp-1801-hysteresis-in-employment-among-disadvantaged-workers.aspx.