The Federal Reserve's Dual Mandate

Note

The Federal Open Market Committee announced substantial revisions to its policy framework in its updated Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, dated August 27, 2020. The Committee’s previous framework can be found here and a guide to the changes can be found here.

The content below is for historical reference and discusses the FOMC’s dual mandate objectives and path for monetary policy under the previous framework.

The monetary policy goals of the Federal Reserve are to foster economic conditions that achieve both stable prices and maximum sustainable employment.

Our two goals of price stability and maximum sustainable employment are known collectively as the "dual mandate."1 The Federal Reserve's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC),2 which sets U.S. monetary policy, has translated these broad concepts into specific longer-run goals and strategies.3

Price stability

The Committee judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the Price Index for Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve's statutory mandate. The Committee has also explicitly noted that the inflation target is symmetric and stated that it "would be concerned if inflation were running persistently above or below this objective."4

Maximum sustainable employment

Many nonmonetary factors affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market, and these may change over time and may not be measurable directly. Accordingly, specifying an explicit goal for employment is not appropriate. Instead, the Committee’s decisions must be informed by a wide range of labor market indicators.

Information about FOMC participants' estimates of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment consistent with the employment mandate can be found in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).5 Most recently, the median Committee participant estimated this rate to be 4.1 percent.

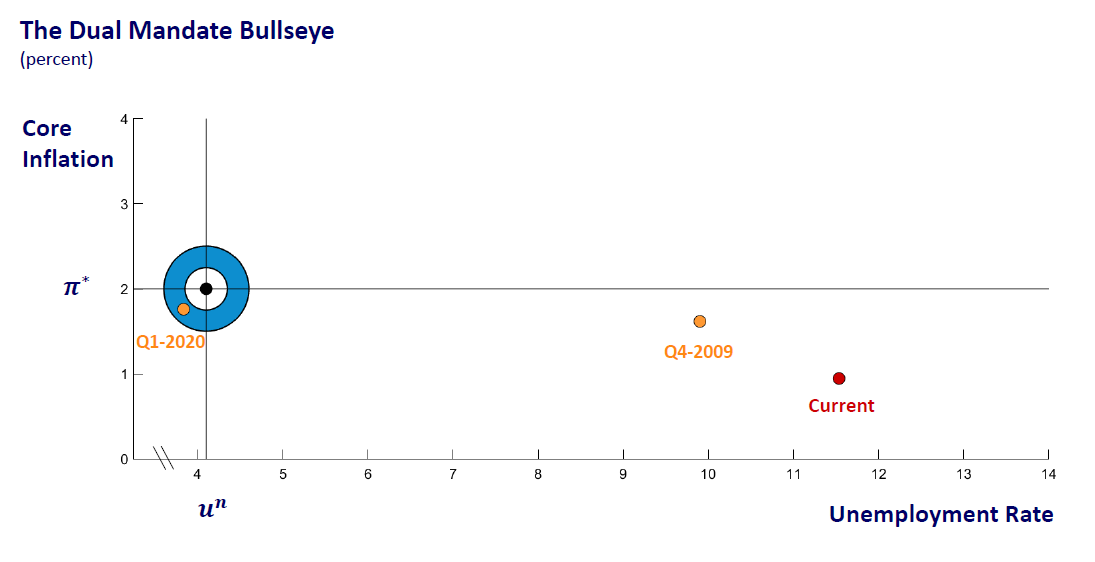

Sources: Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis from Haver Analytics.

Individual dots in the bullseye chart show the combination of the prevailing unemployment rate and inflation rate at various times. The chart provides a means of visualizing the simultaneous progress toward each dual mandate goal. Note that the dot for the first quarter of 2020 is much closer to the bullseye than either the fourth quarter of 2009 dot near the trough of the Great Recession or the current dot. The progress toward our dual mandate objectives made between 2009 and the first quarter of 2020 is largely due to the steady decline in the unemployment rate. In February 2020, on the eve of the pandemic, the unemployment rate was at a 50-year low of 3.5 percent. By April 2020, the unemployment rate had risen to 14.7 percent, and it has improved some since then.6

As for inflation, with the exception of a brief period in mid-2018, core inflation has consistently been below the FOMC’s 2 percent target for most of the post-Great Recession period.7 With the pandemic’s impact on aggregate demand, inflation trends have recently weakened.

Actions taken to limit the community spread of Covid-19 have curbed economic activity, and the unemployment rate has increased sharply.8 With states now in various stages of reopening, FOMC participants generally expect the economic recovery to begin in the second half of this year. Even so, in the June SEP, real gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to show a sharp decline for the year as a whole, with the median FOMC participant forecasting a fall of 6.5 percent. The median outlook then has real GDP rising by 5 percent next year and 3.5 percent in 2022. The unemployment rate is expected to be somewhat above 9 percent at the end of this year and to decline to 5.5 percent by the end of 2022. That is still nearly 1.5 percentage points above the median participant’s estimate of its long-run normal level. The range of growth and unemployment rate forecasts among FOMC participants is quite wide.

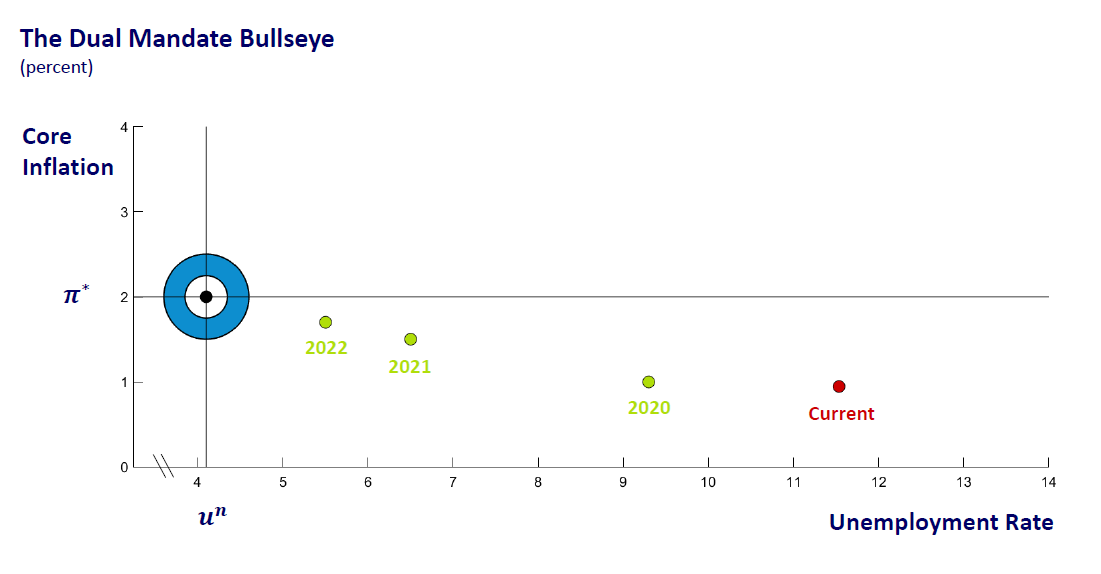

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) from Haver Analytics.

As for our price stability mandate, before the pandemic, even with the long expansion following the Great Recession, core inflation consistently ran below the FOMC’s 2 percent goal. With the pandemic’s negative impact on aggregate demand, inflation has recently moved down significantly, and inflation trends are expected to remain weak. In the June SEP, the median forecast has core PCE inflation for 2020 at just 1.0 percent. The median FOMC participant’s forecast has core PCE inflation rising in the coming years, but to only 1.7 percent by the end of 2022.

Sources: Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis from Haver Analytics.

The bullseye chart summarizes the median FOMC participant’s anticipated progress toward the dual mandate goals. In the latest SEP, almost all participants expected the unemployment rate at the end of 2022 to remain above their estimates of its long-run estimate and the inflation rate to remain below the FOMC’s target through the end of 2022.

Sources: Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis from Haver Analytics.

What should we expect for policy?

The FOMC conducts monetary policy primarily by adjusting the federal funds rate,9 which is our main policy rate. Learn more information about the federal funds rate here.

Prior to the outbreak of Covid-19, the economy was near our dual mandate objectives.10 In December 2019, the median FOMC participant anticipated raising the target range further over the next several years from the 1.5 percent to 1.75 percent target range prevailing at that time toward the median estimate of its long-run level of 2.5 percent. However, by mid-March, states began to order shutdowns for nonessential industries, in an effort to reduce the virus’s spread. Citing the risks posed to economic activity by the public-health measures, the FOMC acted quickly in March and cut the target range for the federal funds rate by 150 basis points to zero to 0.25 percent, its effective lower bound (ELB).11 The Committee also indicated rates would remain low until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals. Given FOMC participants’ recent forecasts, this is likely to be the situation for some time.

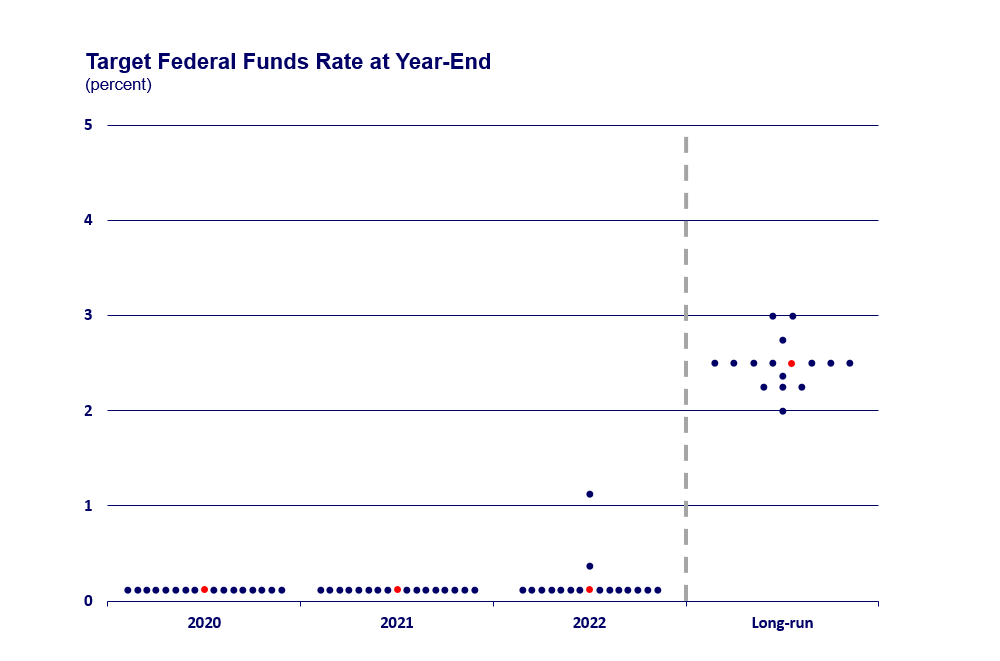

FOMC participants' individual assessments of the appropriate monetary policy supporting their forecasts for the next three years and over the long run are summarized in the Federal Open Market Committee's well-known "dot plot." The most recent assessments made in June 2020 are shown in the chart below. The median assessment for each year and for the long run is indicated by the red dot.

All FOMC participants anticipated that it would be appropriate to maintain the federal funds target at its current range through the end of 2021, and only 2 out of 17 thought one or more rate increases in 2022 would be appropriate. The median FOMC participant expects the federal funds rate to settle over the longer run at 2.5 percent.12

Source: Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) from Haver Analytics.

Notes

1 In 1977, Congress amended the Federal Reserve Act, directing the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee to "maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy's long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates."

2 The members of the FOMC, who vote on monetary policy actions, are the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and the presidents of four other regional Federal Reserve Banks. The presidents of the other eight regional Federal Reserve Banks participate fully in discussions at each meeting and rotate into voting positions on a set schedule.

3 The FOMC's longer-run goals were first articulated in its January 25, 2012, press release and have been reaffirmed annually thereafter. The most recent statement was amended effective January 29, 2019.

4 See note 3.

5 Core inflation strips out the volatile food and energy price components and is a better indicator of underlying inflation trends.

6 For comparison, at its Great Recession peak the unemployment rate briefly reached a high of 10.0 percent in October 2009.

7 Core inflation strips out the volatile food and energy price components and is a better indicator of underlying inflation trends than total inflation.

8 On March 19, 2020, California became the first state to issue a stay-at-home order and shut down all nonessential businesses. Other states soon followed.

9 Specifically, certain financial institutions hold reserve balances at the Federal Reserve (depository institutions, Federal Home Loan Banks, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, etc.). The federal funds rate is the interest rate these institutions charge when they lend reserves to other institutions overnight.

10 In December 2019, the median FOMC participant’s baseline outlook was for continued economic expansion and low unemployment, with inflation rising near our symmetric 2 percent target by the end of 2021.

11 The cuts were made in two separate moves on March 3, 2020, and on March 15, 2020. Both actions were taken between scheduled FOMC meetings. The FOMC and the Board of Governors took numerous other policy actions to support the functioning of financial markets and the flow of credit to households, businesses, and other institutions during the pandemic. More information on the Federal Reserve’s response to the virus can be found here.

12 The projections for the longer-run normal federal funds rate have declined from 4.25 percent in January 2012, when those projections were added to the SEP.